Sanchi

| Sanchi | |

|---|---|

The Great Stupa at Sanchi, Eastern Gateway. | |

Sanchi Stupa Sanchi Stupa | |

| General information | |

| Type | Stupa and surrounding buildings |

| Architectural style | Buddhist |

| Location | Sanchi Town, Madhya Pradesh, India, Asia |

| Construction started | 3rd century BCE |

| Height | 16.46 m (54.0 ft) (dome of the Great Stupa) |

| Dimensions | |

| Diameter | 36.6 m (120 ft) (dome of the Great Stupa) |

| Official name | Buddhist Monument at Sanchi |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 524 |

| Inscription | 1989 (13th Session) |

Coordinates: 23°28′45″N 77°44′23″E / 23.479223°N 77.739683°E Sanchi is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located in 46 kilometres (29 mi) north-east of Bhopal, capital of Madhya Pradesh.

The Great Stupa at Sanchi is one of the oldest stone structures in India, and an important monument of Indian Architecture.[1] It was originally commissioned by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BCE. Its nucleus was a simple hemispherical brick structure built over the relics of the Buddha. It was crowned by the chhatri, a parasol-like structure symbolising high rank, which was intended to honour and shelter the relics. The original construction work of this stupa was overseen by Ashoka, whose wife Devi was the daughter of a merchant of nearby Vidisha. Sanchi was also her birthplace as well as the venue of her and Ashoka's wedding. In the 1st century BCE, four elaborately carved toranas (ornamental gateways) and a balustrade encircling the entire structure were added. The Sanchi Stupa built during Mauryan period was made of bricks. The composite flourished until the 11th century.

Sanchi is the center of a region with a number of stupas, all within a few miles of Sanchi, including Satdhara (9 km to the W of Sanchi, 40 stupas, the Relics of Sariputra and Mahamoggallana, now enshrined in the new Vihara, were unearthed there), Bhojpur (also called Morel Khurd, a fortified hilltop with 60 stupas) and Andher (respectively 11 km and 17 km SE of Sanchi), as well as Sonari (10 km SW of Sanchi).[2][3] Further south, about 100 km away, is Saru Maru. Bharhut is 300 km to the northeast.

Sanchi Stupa is depicted on the reverse side of the Indian currency note of Rs 200 to signify its importance to Indian cultural heritage.[4]

Transport[]

The nearest airport is Bhopal Train from Bhopal Buses from Bhopal and vidisha.

Overview[]

The monuments at Sanchi today comprise a series of Buddhist monuments starting from the Mauryan Empire period (3rd century BCE), continuing with the Gupta Empire period (5th century CE), and ending around the 12th century CE.[5] It is probably the best preserved group of Buddhist monuments in India.[5] The oldest, and also the largest monument, is the Great Stupa also called Stupa No. 1, initially built under the Mauryans, and adorned with one of the Pillars of Ashoka.[5] During the following centuries, especially under the Shungas and the Satavahanas, the Great Stupa was enlarged and decorated with gates and railings, and smaller stupas were also built in the vicinity, especially Stupa No.2, and Stupa No.3.[5]

Simultaneously, various temple structures were also built, down to the Gupta Empire period and later. Altogether, Sanchi encompasses most of the evolutions of ancient Indian architecture and ancient Buddhist architecture in India, from the early stages of Buddhism and its first artistic expression, to the decline of the religion in the subcontinent.[5]

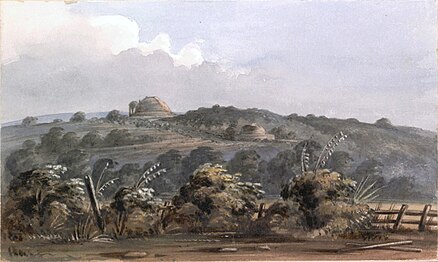

General view of the Stupas at Sanchi by F.C. Maisey, 1851 (The Great Stupa on top of the hill, and Stupa 2 at the forefront)

The Great Stupa (Stupa No.1), started in the 3rd century BCE

Stupa No.2

Stupa No.3

Buddhist Temple, No.17

Mauryan Period (3rd century BCE)[]

The "Great Stupa" at Sanchi is the oldest structure and was originally commissioned by the emperor Ashoka the Great of the Maurya Empire in the 3rd century BCE.[6] Its nucleus was a hemispherical brick structure built over the relics of the Buddha,[6] with a raised terrace encompassing its base, and a railing and stone umbrella on the summit, the chatra, a parasol-like structure symbolizing high rank.[7][8] The original Stupa only had about half the diameter of today's stupa, which is the result of enlargement by the Sungas. It was covered in brick, in contrast to the stones that now cover it.[7]

According to one version of the Mahavamsa, the Buddhist chronicle of Sri Lanka, Ashoka was closely connected to the region of Sanchi. When he was heir-apparent and was journeying as Viceroy to Ujjain, he is said to have halted at Vidisha (10 kilometers from Sanchi), and there married the daughter of a local banker. She was called Devi and later gave Ashoka two sons, Ujjeniya and Mahendra, and a daughter Sanghamitta. After Ashoka's accession, Mahendra headed a Buddhist mission, sent probably under the auspices of the Emperor, to Sri Lanka, and that before setting out to the island he visited his mother at Chetiyagiri near Vidisa, thought to be Sanchi. He was lodged there in a sumptuous vihara or monastery, which she herself is said to have had erected.[9]

Ashoka pillar[]

A pillar of finely polished sandstone, one of the Pillars of Ashoka, was also erected on the side of the main Torana gateway. The bottom part of the pillar still stands. The upper parts of the pillar are at the nearby Sanchi Archaeological Museum. The capital consists in four lions, which probably supported a Wheel of Law,[12] as also suggested by later illustrations among the Sanchi reliefs. The pillar has an Ashokan inscription (Schism Edict)[12] and an inscription in the ornamental Sankha Lipi from the Gupta period.[6] The Ashokan inscription is engraved in early Brahmi characters. It is unfortunately much damaged, but the commands it contains appear to be the same as those recorded in the Sarnath and Kausambi edicts, which together form the three known instances of Ashoka's "Schism Edict". It relates to the penalties for schism in the Buddhist sangha:

... the path is prescribed both for the monks and for the nuns. As long as (my) sons and great-grandsons (shall reign; and) as long as the Moon and the Sun (shall endure), the monk or nun who shall cause divisions in the Sangha, shall be compelled to put on white robes and to reside apart. For what is my desire? That the Sangha may be united and may long endure.

The pillar, when intact, was about 42 feet in height and consisted of round and slightly tapering monolithic shaft, with bell-shaped capital surmounted by an abacus and a crowning ornament of four lions, set back to back, the whole finely finished and polished to a remarkable luster from top to bottom. The abacus is adorned with four flame palmette designs separated one from the other by pairs of geese, symbolical perhaps of the flock of the Buddha's disciples. The lions from the summit, though now quite disfigured, still testify to the skills of the sculptors.[14]

The sandstone out of which the pillar is carved came from the quarries of Chunar several hundred miles away, implying that the builders were able to transport a block of stone over forty feet in length and weighing almost as many tons over such a distance. They probably used water transport, using rafts during the rainy season up until the Ganges, Jumna and Betwa rivers.[14]

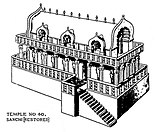

Temple 40[]

Another structure which has been dated, at least partially, to the 3rd century BCE, is the so-called Temple 40, one of the first instances of free-standing temples in India.[15] Temple 40 has remains of three different periods, the earliest period dating to the Maurya age, which probably makes it contemporary to the creation of the Great Stupa. An inscription even suggests it might have been established by Bindusara, the father of Ashoka.[16] The original 3rd century BCE temple was built on a high rectangular stone platform, 26.52×14×3.35 metres, with two flights of stairs to the east and the west. It was an apsidal hall, probably made of timber. It was burnt down sometime in the 2nd century BCE.[17][18]

Later, the platform was enlarged to 41.76×27.74 metres and re-used to erect a pillared hall with fifty columns (5×10) of which stumps remain. Some of these pillars have inscriptions of the 2nd century BCE. In the 7th or 8th century a small shrine was established in one corner of the platform, re-using some of the pillars and putting them in their present position.[19][18]

Approximate reconstitution of the Great Stupa with its pillar of Ashoka, under the Mauryas circa 260 BCE. |

|

Shunga period (2nd century BCE)[]

On the basis of Ashokavadana, it is presumed that the stupa may have been vandalized at one point sometime in the 2nd century BCE, an event some have related to the rise of the Shunga emperor Pushyamitra Shunga who overtook the Mauryan Empire as an army general. It has been suggested that Pushyamitra may have destroyed the original stupa, and his son Agnimitra rebuilt it.[20] The original brick stupa was covered with stone during the Shunga period.

Given the rather decentralized and fragmentary nature of the Shunga state, with many cities actually issuing their own coinage, as well as the relative dislike of the Shungas for Buddhism, some authors argue that the constructions of that period in Sanchi cannot really be called "Shunga". They were not the result of royal sponsorship, in contrast with what happened during the Mauryas, and most of the dedications at Sanchi were private or collective, rather than the result of royal patronage.[21]

The style of the Shunga period decorations at Sanchi bear a close similarity to those of Bharhut, as well as the peripheral balustrades at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya.

Great Stupa (No 1)[]

During the later rule of the Shunga, the stupa was expanded with stone slabs to almost twice its original size. The dome was flattened near the top and crowned by three superimposed parasols within a square railing. With its many tiers it was a symbol of the dharma, the Wheel of the Law. The dome was set on a high circular drum meant for circumambulation, which could be accessed via a double staircase. A second stone pathway at ground level was enclosed by a stone balustrade. The railings around Stupa 1 do not have artistic reliefs. These are only slabs, with some dedicatory inscriptions. These elements are dated to circa 150 BCE,[22] or 175–125 BCE.[23] Although the railings are made up of stone, they are copied from a wooden prototype, and as John Marshall has observed the joints between the coping stones have been cut at a slant, as wood is naturally cut, and not vertically as stone should be cut. Besides the short records of the donors written on the railings in Brahmi script, there are two later inscriptions on the railings added during the time of the Gupta Period.[24] Some reliefs are visible on the stairway balustrade, but they are probably slightly later than those at Stupa No2,[25] and are dated to 125–100 BCE.[23] Some authors consider that these reliefs, rather crude and without obvious Buddhist connotations, are the oldest reliefs of all Sanchi, slightly older even than the reliefs of Sanchi Stupa No.2.[23]

| Great Stupa (No1). Shunga period structures and decorations (2nd century BCE) | |

Great Stupa (Stupa expansion and balustrades only are Shunga). Undecorated ground railings dated to approximately 150 BCE.[22] Some reliefs on the stairway balustrade. |

Stairway balustrade reliefs

|

Stupa No. 2: the first Buddhist reliefs[]

The stupas which seem to have been commissioned during the rule of the Shungas are the Second and then the Third stupas (but not the highly decorated gateways, which are from the following Satavahana period, as known from inscriptions), following the ground balustrade and stone casing of the Great Stupa (Stupa No 1). The reliefs are dated to circa 115 BCE for the medallions, and 80 BCE for the pillar carvings,[27] slightly before the reliefs of Bharhut for the earliest, with some reworks down to the 1st century CE.[22][27]

Stupa No. 2 was established later than the Great Stupa, but it is probably displaying the earliest architectural ornaments.[25] For the first time, clearly Buddhist themes are represented, particularly the four events in the life of the Buddha that are: the Nativity, the Enlightenment, the First Sermon and the Decease.[30]

The decorations of Stupa No. 2 have been called "the oldest extensive stupa decoration in existence",[28] and this Stupa is considered as the birthplace of Jataka illustrations.[29] The reliefs at Stupa No.2 bear mason marks in Kharoshthi, as opposed to the local Brahmi script.[26] This seems to imply that foreign workers from the north-west (from the region of Gandhara, where Kharoshthi was the current script) were responsible for the motifs and figures that can be found on the railings of the stupa.[26] Foreigners from Gandhara are otherwise known to have visited the region around the same time: in 115 BCE, the embassy of Heliodorus from Indo-Greek king Antialkidas to the court of the Sungas king Bhagabhadra in nearby Vidisha is recorded, in which Heliodorus established the Heliodorus pillar in a dedication to Vāsudeva. This would indicate that relations had improved at that time, and that people traveled between the two realms.[31]

Stupa No. 2 Shunga period, but mason's marks in Kharoshti point to craftsmen from the north-west (region of Gandhara) for the earliest reliefs (circa 115 BCE).[26][27][22] |

|

Stupa No. 3[]

Stupa No. 3 was built during the time of the Shungas, who also built the railing around it as well as the staircase. The Relics of Sariputra and Mahamoggallana, the disciples of the Buddha are said to have been placed in Stupa No. 3, and relics boxes were excavated tending to confirm this.[33]

The reliefs on the railings are said to be slightly later than those of Stupa No. 2.[23]

The single torana gateway oriented to the south is not Shunga, and was built later under the Satavahanas, probably circa 50 BCE.[23]

Stupa No. 3 (Stupa and balustrades only are Shunga). |

|

Sunga Pillar[]

Pillar 25 at Sanchi is also attributed to the Sungas, in the 2nd–1st century BCE, and is considered as similar in design to the Heliodorus pillar, locally called Kham Baba pillar, dedicated by Heliodorus, the ambassador to the Indo-Greek king Antialkidas, in nearby Vidisha circa 100 BCE.[35] That it belongs to about the period of the Sunga, is clear alike from its design and from the character of the surface dressing.

The height of the pillar, including the capital, is 15 ft, its diameter at the base 1 ft. 4 in. Up to a height of 4 ft. 6 in. the shaft is octagonal; above that, sixteen-sided. In the octagonal portion all the facets are flat, but in the upper section the alternate facets are fluted, the eight other sides being produced by a concave chamfering of the arrises of the octagon. This method of finishing off the arris at the point of transition between the two sections are features characteristic of the second and first centuries BCE. The west side of the shaft is split off, but the tenon at the top, to which the capital was mortised, is still preserved. The capital is of the usual bell-shaped Persepolitan type, with lotus leaves falling over the shoulder of the bell. Above this is a circular cable necking, then a second circular necking relieved by a bead and lozenge pattern, and, finally, a deep square abacus adorned with a railing in relief. The crowning feature, probably a lion, has disappeared.[35]

Satavahana period (1st century BCE – 1st century CE)[]

Dated circa 50 BCE- 0 CE.

The Satavahana Empire under Satakarni II conquered eastern Malwa from the Shungas.[38] This gave the Satavahanas access to the Buddhist site of Sanchi, in which they are credited with the building of the decorated gateways around the original Mauryan Empire and Sunga stupas.[39] From the 1st century BCE, the highly decorated gateways were built. The balustrade and the gateways were also colored.[6] Later gateways/toranas are generally dated to the 1st century CE.[25]

The Siri-Satakani inscription in the Brahmi script records the gift of one of the top architraves of the Southern Gateway by the artisans of the Satavahana king Satakarni II:[36]