Sand Creek massacre

| Sand Creek massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Colorado War, American Indian Wars, American Civil War | |||||||

A depiction of one scene at Sand Creek by witness Howling Wolf | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Cheyenne Arapaho | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Black Kettle | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 700[1] | 70–200 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

25 killed 51 wounded[2] | 150+ (mostly women and children) killed[2] | ||||||

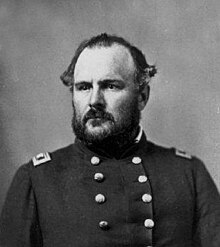

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by the U.S. Army in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of the Third Colorado Cavalry[3] under the command of U.S. Volunteers Colonel John Chivington attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho people in southeastern Colorado Territory,[4] killing and mutilating an estimated 70 to 500 Native American people, about two-thirds of whom were women and children.[2][5] The location has been designated the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and is administered by the National Park Service. This was part of a series of events known as the Colorado War and was preceded by the Hungate massacre.[6]

Background[]

Treaty of Fort Laramie[]

By the terms of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie between the United States and seven Indian nations, including the Cheyenne and Arapaho,[7] the United States recognized that the Cheyenne and Arapaho held a vast territory encompassing the lands between the North Platte River and the Arkansas River, and eastward from the Rocky Mountains to western Kansas. This area included present-day southeastern Wyoming, southwestern Nebraska, most of eastern Colorado, and the westernmost portions of Kansas.[8]

In November 1858, however, the discovery of gold in the Rocky Mountains in Colorado,[9] then part of the Kansas Territory,[10] brought on the Pikes Peak Gold Rush. Immigrants flooded across Cheyenne and Arapaho lands. They competed for resources, and some settlers tried to stay.[9] Colorado territorial officials pressured federal authorities to redefine the extent of Indian lands in the territory,[8] and in the fall of 1860, A.B. Greenwood, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, arrived at Bent's New Fort, along the Arkansas River, to negotiate a new treaty.[9]

Native lands restricted[]

On February 18, 1861, six chiefs of the Southern Cheyenne and four of the Arapaho signed the Treaty of Fort Wise with the United States,[11] in which they ceded most of the lands designated to them by the Fort Laramie treaty.[8] The Cheyenne chiefs included Black Kettle, White Antelope (Vó'kaa'e Ohvó'komaestse),[12] Lean Bear, Little Wolf, and Tall Bear; the Arapaho chiefs included Little Raven, Storm, Shave-Head, Big Mouth, and Niwot, or Left Hand.[11] The Cheyenne warriors denounced the chiefs who signed the treaty and even threatened them with death if they attempted to carry out the treaty's provisions.[13]

The new reserve, less than 1/13th the size of the territory recognized in the 1851 treaty,[8] was located in eastern Colorado,[10] between the Arkansas River and Sand Creek.[8] Most bands of the Cheyenne, including the Dog Soldiers, a militaristic band of Cheyenne and Lakota that had originated in the late 1830s, were angry at the chiefs who had signed the treaty. They disavowed the treaty—which never received the blessing of the Council of 44, the supreme tribal authority—and refused to abide by its constraints.[14] They continued to live and hunt in the bison-rich lands of eastern Colorado and western Kansas, and became increasingly belligerent over the tide of white migration across their lands. Tensions were high, particularly in the Smoky Hill River country of Kansas, along which whites had opened a new trail to the gold fields.[15] Cheyenne who opposed the treaty said it had been signed by a small minority of the chiefs without the consent or approval of the rest of the tribe, that the signatories had not understood what they signed, and that they had been bribed to sign by a large distribution of gifts. Officials took the position that Indians who refused to abide by it were hostile and planning a war.[16] The Cheyenne started committing minor offenses in 1861. These offenses went unpunished and, subsequently, became more significant. The desire for war was so strong with the Cheyenne that Agent Lorey urged Governor Evans to treat with the Cheyenne anew in 1863. As agreed, Governor Evans went out to meet with the chiefs, but they did not show up to the appointed place. The governor sent his guide, Elbridge Gerry, out to try to find the chiefs. Gerry returned two weeks later saying that a council had been held wherein the chiefs decided not to meet with Governor Evans. Bull Bear offered to meet with the governor, but his warriors would not allow it.[13]

Escalation of hostilities[]

At the end of 1863 and in the beginning of 1864, word was received that a coalition was to be formed among the plains tribes to "drive the whites out of the country."[13] In the spring and summer of 1864, the Sioux, Comanches, Kiowas, Cheyennes, and Arapahos were engaged in active hostilities which led to the murder of numerous civilians, the destruction of livestock and crops, supplies to the region being cut off, and the Colorado settlers in danger of starvation or murder at the hands of the plains tribes.[13]

On April 13, a herdsman working for Irving, Jackmann & Company reported that Cheyennes and Arapahos had driven off 60 oxen and 12 horses and mules from their camp south of Denver. A small contingent of soldiers, led by Lieutenant Clark Dunn, was sent to repossess the livestock. The ensuing confrontation resulted in the death of four of the soldiers, and the tribes maintained possession of the stolen livestock.[13]

On May 16, less than 15 months after meeting President Lincoln in Washington,[17] Lean Bear, Black Kettle, and others in the tribe were camping on their buffalo hunting grounds near Ash Creek. The 1st Colorado Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant , approached the group. Positive that this would be a peaceful encounter, Lean Bear went alone to meet the militia to show his peaceful intentions. On his chest, Lean Bear proudly wore his peace medal that he had received on his trip to Washington D.C. in 1863. In his hand, he held an official document signed by Lincoln stating that he was peaceful and friendly with whites.[18] What Lean Bear did not realize was that Eayre's troops were operating under orders from Colonel John M. Chivington to "kill Cheyennes whenever and wherever found."[19] Eayre ordered his men to shoot Lean Bear, who was wounded and fell off his horse. He was then shot repeatedly by the soldiers as they rode past his body on the ground.[18] Newspaper reports and books from the era report that Cheyenne warriors attacked settlers and committed a number of atrocities in July and August of 1864[20][13]

The beginning of the American Civil War in 1861 led to the organization of military forces in Colorado Territory. However, the attention of the Federal Government was firmly fixed on quelling the rebels in the South. As a result, there was no significant military protection of wagon trains, settlers, settlements, communication lines, and supply wagons in the region. By the summer of 1864, nearly every stage was being attacked, emigrants were being cut off, and settlements were being raided continually.[13] The settlers abandoned their farms and ranches and began seeking refuge in the major settlements such as Denver. A coordinated attack was carried out on August 8, 1864, where all the existing stage lines in the region were attacked.[13] Between August 11 and September 7, Governor Evans sent multiple letters to Secretary of War Edward Stanton in an attempt to furnish military aid, but Stanton was unable to pull the Second Colorado Volunteers, led by Colonel Ford, off of the eastern Civil War front.[13] As a result of the repeated calls for aid, authorization was granted to call up "one-hundred-days' men" to form the Third Colorado Volunteers.

In 1864, before the events of the Massacre of Sand Creek, there were 32 Indian attacks on record. These resulted in the death of 96 settlers, 21 being wounded, and eight being captured. Between 250 and 300 head of livestock were stolen, twelve wagon trains and stagecoaches were attacked, robbed or destroyed, and nine ranches and settlements were raided.[21]

I am not a big war chief, but all the soldiers in this country are at my command. My rule of fighting white men or Indians is to fight them until they lay down their arms and submit to military authority. They are nearer to Major Wynkoop than any one else, and they can go to him when they get ready to do that.

— Col. John Milton Chivington, September 28, 1864 peace council in Denver[13]

Governor Evans promises war[]

As the conflict between the Indians and settlers and soldiers in Colorado continued, the tribes would make war during the spring and summer months until subsistence became difficult to obtain. The tribes would then earnestly seek to make peace during the winter months, when they would stock up on supplies, arms, and munitions, until fairer weather would return and the war could be commenced anew. In July 1864, Colorado governor John Evans sent a circular to the Plains Indians, inviting those who were friendly to go to a place of safety at Fort Lyon on the eastern plains, where their people would be given provisions and protection by the United States troops.[22] The circular itself was dated June 27, 1864. It wasn't until three months later, September 28, that the Cheyenne came to Denver to have peace talks with Governor Evans.[13] At this conference, the chiefs were told by Governor Evans that peace was not possible at that point and that "whatever peace they make must be with the soldiers, and not with me."[13] At this council, White Antelope said that he feared the soldiers might kill some of his people while he was there. Governor Evans told him that there was great danger of it, and then he told White Antelope that one of the military chiefs (Colonel Chivington) was present and could tell the tribes what was necessary to secure peace. Governor Evans made clear that the purpose of the circular was not to extend peace, but rather it was an attempt to bring in the Indians who were friendly and were exposed to repudiation by the other tribes as a result.[23] At the September 28 meeting, Governor Evans told the chiefs that peace was not possible in no uncertain terms. Evans told the chiefs, "The time when you can make war best is in the summer; when I can make war best is in the winter. You, so far, have had the advantage. My time is just coming."[13] The Indians who appeared and were subsisted at Fort Lyon beginning around November 6, 1864, namely 652 Arapaho under Chief Little Raven, were undoubtedly hostile. The 600 Cheyenne who appeared at the fort attempting to enter in a similar manner were turned away and denied protection and subsistence by Major Anthony.[13]

Attack[]

The Cheyenne camp near Fort Lyon[]

Black Kettle, leading chief of around 163 mostly Southern Cheyenne, had led his band, joined by some Arapahos under Chief Niwot, to Fort Lyon in compliance with provisions of a peace parley held in Denver in September 1864.[24] After a while, the American Indians were asked to relocate to Big Sandy Creek, less than 40 miles northwest of Fort Lyon, under the threat of their safety.[25] The Dog Soldiers, who had been responsible for many of the attacks and raids on whites, were not part of this encampment.

Most tribal warriors stood their ground, refusing to leave their home under the guise of a threat, leaving only about 75 men, plus all the women and children in the village. The men who remained were mostly too old or too young to hunt. Black Kettle flew a U.S. flag, with a white flag tied beneath it,[25] over his lodge, as the Fort Lyon commander had advised him. This was to show he was friendly and forestall any attack by the Colorado soldiers.[26] Peace chief Ochinee, who tried to broker peace for the Cheyenne, was among those who were killed. Ochinee and 160 other people, most of whom were children and women, were killed.[27]

Grandfather Ochinee (One-Eye) escaped from the camp, but seeing all that his people were to be slaughtered, he deliberately chose to go back into the one-sided battle and die with them.

— Mary Prowers Hudnal, daughter of Amache Prowers[28]

Chivington attacks the camp[]

Meanwhile, Chivington and 425 men of the 3rd Colorado Cavalry rode to Fort Lyon arriving on November 28, 1864. Once at the fort, Chivington took command of 250 men of the 1st Colorado Cavalry and maybe as many as 12 men of the , then set out for Black Kettle's encampment. James Beckwourth, noted frontiersman, acted as guide for Chivington.[29] The following morning, Chivington gave the order to attack. Two officers, Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer, commanding Company D and Company K of the First Colorado Cavalry, refused to obey and told their men to hold fire.[30]

However, the rest of Chivington's men immediately attacked the village. Ignoring the U.S. flag and a white flag that was run up shortly after the attack began, they murdered as many of the Indians as they could.

I saw the bodies of those lying there cut all to pieces, worse mutilated than any I ever saw before; the women cut all to pieces ... With knives; scalped; their brains knocked out; children two or three months old; all ages lying there, from sucking infants up to warriors ... By whom were they mutilated? By the United States troops ...

— John S. Smith, Congressional Testimony of Mr. John S. Smith, 1865[31]

I saw one squaw lying on the bank, whose leg had been broken. A soldier came up to her with a drawn sabre. She raised her arm to protect herself; he struck, breaking her arm. She rolled over, and raised her other arm; he struck, breaking that, and then left her with out killing her. I saw one squaw cut open, with an unborn child lying by her side.

— Robert Bent, New York Tribune, 1879[25]

There was one little child, probably three years old, just big enough to walk through the sand. The Indians had gone ahead, and this little child was behind, following after them. The little fellow was perfectly naked, travelling in the sand. I saw one man get off his horse at a distance of about seventy-five yards and draw up his rifle and fire. He missed the child. Another man came up and said, 'let me try the son of a b-. I can hit him.' He got down off his horse, kneeled down, and fired at the little child, but he missed him. A third man came up, and made a similar remark, and fired, and the little fellow dropped.

— Major Anthony, New York Tribune, 1879[32]

Fingers and ears were cut off the bodies for the jewelry they carried. The body of White Antelope, lying solitarily in the creek bed, was a prime target. Besides scalping him the soldiers cut off his nose, ears, and testicles-the last for a tobacco pouch ...

— Stan Hoig[33]

Jis' to think of that dog Chivington and his dirty hounds, up thar at Sand Creek. His men shot down squaws, and blew the brains out of little innocent children. You call sich soldiers Christians, do ye? And Indians savages? What der yer s'pose our Heavenly Father, who made both them and us, thinks of these things? I tell you what, I don't like a hostile red skin any more than you do. And when they are hostile, I've fought 'em, hard as any man. But I never yet drew a bead on a squaw or papoose, and I despise the man who would.

— Kit Carson to Col. James Rusling[34]

The natives, lacking artillery, could not make much resistance. Some of the natives cut horses from the camp's herd and fled up Sand Creek or to a nearby Cheyenne camp on the headwaters of the Smoky Hill River. Others, including trader George Bent, fled upstream and dug holes in the sand beneath the banks of the stream. They were pursued by the troops and fired on, but many survived.[35] Cheyenne warrior Morning Star said that most of the Indian dead were killed by cannon fire, especially those firing from the south bank of the river at the people retreating up the creek.[36]

In testimony before a Congressional committee investigating the massacre, Chivington claimed that as many as 500 to 600 Indian warriors were killed.[37] Historian Alan Brinkley wrote that 133 Indians were killed, 105 of whom were women and children.[38] White eye-witness John S. Smith reported that 70 to 80 Indians were killed, including 20 to 30 warriors,[2] which agrees with Brinkley's figure as to the number of men killed. George Bent, the son of the American William Bent and a Cheyenne mother, who was in the village when the attack came and was wounded by the soldiers, gave two different accounts of the natives' loss. On March 15, 1889, he wrote to Samuel F. Tappan that 137 people were killed: 28 men and 109 women and children.[39] However, on April 30, 1913, when he was very old, he wrote that "about 53 men" and "110 women and children" were killed and many people wounded.[40]

Although initial reports indicated 10 soldiers killed and 38 wounded, the final tally was four killed and 21 wounded in the 1st Colorado Cavalry and 20 killed or mortally wounded and 31 other wounded in the 3rd Colorado Cavalry; adding up to 24 killed and 52 wounded.[2] Dee Brown wrote that some of Chivington's men were drunk and that many of the soldiers' casualties were due to friendly fire,[41] but neither of these claims is supported by Gregory F. Michno[42] or Stan Hoig[43] in their books devoted to the massacre.

Before Chivington and his men left the area, they plundered the teepees and took the horses. After the smoke cleared, Chivington's men came back and killed many of the wounded. They also scalped many of the dead, regardless of whether they were women, children, or infants. Chivington and his men dressed their weapons, hats, and gear with scalps and other body parts, including human fetuses and male and female genitalia.[44] They also publicly displayed these battle trophies in Denver's Apollo Theater and area saloons. Three Indians who remained in the village are known to have survived the massacre: George Bent's brother Charlie Bent, and two Cheyenne women who were later turned over to William Bent.[45]

According to western author and historian Larry McMurtry, the son of Chivington's scout John Smith (by an Indian mother) was in the camp, survived the attack and was "executed" afterwards.[46]

Aftermath[]

The Sand Creek Massacre resulted in a heavy loss of life, mostly among Cheyenne and Arapaho women and children. The hardest hit by the massacre were the Wutapai, Black Kettle's band. Perhaps half of the Hevhaitaniu were lost, including the chiefs Yellow Wolf and Big Man. The Oivimana, led by War Bonnet, lost about half their number. There were heavy losses to the Hisiometanio (Ridge Men) under White Antelope. Chief One Eye was also killed, along with many of his band. The Suhtai clan and the Heviqxnipahis clan under chief Sand Hill experienced relatively few losses. The Dog Soldiers and the Masikota, who by that time had allied, were not present at Sand Creek.[47] Of about ten lodges of Arapaho under Chief Left Hand, representing about 50 or 60 people, only a handful escaped with their lives.[48]

After hiding all day above the camp in holes dug beneath the bank of Sand Creek, the survivors there, many of whom were wounded, moved up the stream and spent the night on the prairie. Trips were made to the site of the camp but very few survivors were found there. After a cold night without shelter, the survivors set out toward the Cheyenne camp on the headwaters of the Smoky Hill River. They soon met up with other survivors who had escaped with part of the horse herd, some returning from the Smoky Hill camp where they had fled during the attack. They then proceeded to the camp, where they received assistance.[49]

The massacre disrupted the traditional Cheyenne power structure, because of the deaths of eight members of the Council of Forty-Four. White Antelope, One Eye, Yellow Wolf, Big Man, Bear Man, War Bonnet, Spotted Crow, and Bear Robe were all killed, as were the headmen of some of the Cheyenne military societies.[50] Among the chiefs killed were most of those who had advocated peace with white settlers and the U.S. government.[51] The net effect of the murders and ensuing weakening of the peace faction exacerbated the developing social and political rift. Traditional council chiefs, mature men who sought consensus and looked to the future of their people, and their followers, were opposed by the younger and more militaristic Dog Soldiers.

Beginning in the 1830s, the Dog Soldiers had evolved from a Cheyenne military society of that name into a separate band of Cheyenne and Lakota warriors. They took as their territory the area around the headwaters of the Republican and Smoky Hill rivers in southern Nebraska, northern Kansas, and the northeastern Colorado Territory. By the 1860s, as conflict between Indians and encroaching whites intensified, the Dog Soldiers and military societies within other Cheyenne bands countered the influence of the traditional Council of Forty-Four chiefs who, as more mature men, took a larger view and were more likely to favor peace with the whites.[52] To the Dog Soldiers, the Sand Creek massacre illustrated the folly of the peace chiefs' policy of accommodating the whites through treaties such as the first Treaty of Fort Laramie and the Treaty of Fort Wise.[8] They believed their militant position toward the whites was justified by the massacre.[52]

The events at Sand Creek dealt a fatal blow to the traditional Cheyenne clan system and the authority of its Council of Chiefs. It had already been weakened by the numerous deaths due to the 1849 cholera epidemic, which killed perhaps half the Southern Cheyenne population, especially the Masikota and Oktoguna bands.[53] It was further weakened by the emergence of the separate Dog Soldiers band.[54]

Retaliation[]

After the brutal slaughter of those who supported peace, many of the Cheyenne, including the great warrior Roman Nose, and many Arapaho joined the Dog Soldiers. They sought revenge on settlers throughout the Platte valley, including an 1865 attack on what became Fort Caspar, Wyoming.

Following the massacre, the survivors reached the camps of the Cheyenne on the Smokey Hill and Republican rivers. The war pipe was smoked and passed from camp to camp among the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors in the area. In January 1865, they planned and carried out an attack with 1,000 warriors on the stage station and fort, then called Camp Rankin, at present-day Julesburg, Colorado. This was followed by numerous raids along the South Platte both east and west of Julesburg, and a second raid on the town of Julesburg in early February. The associated bands captured much loot and killed many white settlers, including men, women and children. The bulk of the Indians then moved north into Nebraska on their way to the Black Hills and the Powder River Country.[55]

Black Kettle continued to speak for peace and did not join in the second raid or in the journey to the Powder River country. He left the camp and returned with 80 lodges to the Arkansas River to seek peace with the Coloradans.[56]

Official investigations[]

Initially, the Sand Creek engagement was reported as a victory against a brave and numerous foe. Within weeks, however, witnesses and survivors began telling stories of a possible massacre. Several investigations were conducted—two by the military, and one by the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. The panel declared:[57]

As to Colonel Chivington, your committee can hardly find fitting terms to describe his conduct. Wearing the uniform of the United States, which should be the emblem of justice and humanity; holding the important position of commander of a military district, and therefore having the honor of the government to that extent in his keeping, he deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre which would have disgraced the veriest savage among those who were the victims of his cruelty. Having full knowledge of their friendly character, having himself been instrumental to some extent in placing them in their position of fancied security, he took advantage of their in-apprehension and defenceless condition to gratify the worst passions that ever cursed the heart of man.

Whatever influence this may have had upon Colonel Chivington, the truth is that he surprised and murdered, in cold blood, the unsuspecting men, women, and children on Sand creek, who had every reason to believe they were under the protection of the United States authorities, and then returned to Denver and boasted of the brave deed he and the men under his command had performed.

In conclusion, your committee are of the opinion that for the purpose of vindicating the cause of justice and upholding the honor of the nation, prompt and energetic measures should be at once taken to remove from office those who have thus disgraced the government by whom they are employed, and to punish, as their crimes deserve, those who have been guilty of these brutal and cowardly acts.

Statements taken by Major Edward W. Wynkoop and his adjutant substantiated the later accounts of survivors. These statements were filed with his reports and can be found in the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, copies of which were submitted as evidence in the Joint Committee of the Conduct of the War and in separate hearings conducted by the military in Denver. Lieutenant James D. Cannon describes the mutilation of human genitalia by the soldiers, "men, women, and children's privates cut out. I heard one man say that he had cut a woman's private parts out and had them for exhibition on a stick. I heard of one instance of a child, a few months old, being thrown into the feed-box of a wagon, and after being carried some distance, left on the ground to perish; I also heard of numerous instances in which men had cut out the private parts of females and stretched them over their saddle-bows, and some of them over their hats."[58]

During these investigations, numerous witnesses came forward with damning testimony, almost all of which was corroborated by other witnesses. One witness, Captain Silas Soule, who had ordered the men under his command not to fire their weapons, was murdered in Denver just weeks after offering his testimony. However, despite the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the Wars' recommendation, no charges were brought against those who committed the massacre. Chivington was beyond the reach of army justice because he'd already resigned his commission. The closest thing to a punishment he suffered was the effective end of his political aspirations.

In his autobiographical Memories of a Lifetime in the Pike's Peak Region, , an 18-year-old cavalryman who was later one of the founders of Colorado Springs, defended Chivington, having claimed instead that the Indian women and children were not attacked, though a few who did not leave the camp were killed once the fighting began. He insisted that the number of warriors in the village was equal to the force of the Colorado cavalry. Chivington, claimed Howbert, was retaliating for Indian attacks on wagon trains and settlements in Colorado and for the torture and the killings of citizens during the preceding three years. Howbert said the evidence of the previous Indian attacks on the settlers was shown by their confiscation of "more than a dozen scalps of white people, some of them from the heads of women and children."[59] Howbert claimed that the account of the battle to the United States Congress made by Lieutenant Col. Samuel F. Tappan was inaccurate, accusing Tappan of giving a false view of the battle because Tappan and Chivington had been military rivals.[59]

A monument installed on the Colorado State Capitol grounds in 1909 lists Sand Creek as one of the "battles and engagements" fought by Colorado troops in the American Civil War. In 2002, the Colorado Historical Society (now History Colorado), authorized by the Colorado General Assembly, added an additional plaque to the monument, which states that the original designers of the monument "mischaracterized" Sand Creek by calling it a battle.[60]

Little Arkansas Treaty[]

After the actual details of the massacre became widely known, the United States federal government sent a blue ribbon commission whose members were respected by the Indians, and the Treaty of the Little Arkansas[61] was signed in 1865. It promised the Indians free access to the lands south of the Arkansas River, excluded them from the Arkansas River north to the Platte River, and promised land and cash reparations to the surviving descendants of Sand Creek victims.

However, the treaty was abrogated by Washington less than two years later, all major provisions ignored, and instead the Medicine Lodge Treaty reduced the reservation lands by 90%, located in much less desirable sites in Oklahoma. Later government actions further reduced the size of the reservations.

Remembrance[]

The site, on Big Sandy Creek in Kiowa County, is now preserved by the National Park Service. The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site was dedicated on April 28, 2007, almost 142 years after the massacre.[62] The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have preserved 640 acres of Sand Creek and deeded it to the national historic site.[63]

The Sand Creek Massacre Trail in Wyoming follows the paths of the Northern Arapaho and Cheyenne in the years after the massacre.[64] It traces them to their supposed wintering on the Wind River Indian Reservation near Riverton in central Wyoming, where the Arapaho remain today. The trail passes through Cheyenne, Laramie, Casper, and Riverton en route to Ethete in Fremont County on the reservation. In recent years, Arapaho youth have taken to running the length of the trail as a test of endurance. Alexa Roberts, superintendent of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, has said that the trail represents a living portion of the history of the two tribes.

An exhibit about Sand Creek, titled Collision: The Sand Creek Massacre 1860s–Today, opened in 2012 with the new History Colorado Center in Denver. The exhibit immediately drew criticism from members of the Northern Cheyenne tribe. In April 2013, History Colorado agreed to close the exhibit to public view while consultations were made with the Northern Cheyenne.[65]

On December 3, 2014, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper formally apologized to descendants of Sand Creek massacre victims gathered in Denver to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the event. Hickenlooper stated, "We should not be afraid to criticize and condemn that which is inexcusable. ... On behalf of the State of Colorado, I want to apologize. We will not run from this history."[66][67]

In 2015, construction of a memorial to the Sand Creek Massacre victims began on the Colorado Capitol grounds.[68][dead link][needs update]

In popular culture[]

The Sand Creek massacre has been depicted or referenced in multiple works, spanning a variety of media. It forms the climax of the 1909 novel Sulle frontiere del Far-West by the Italian writer of adventure stories Emilio Salgari (1862 - 1911), creator of Sandokan.

Comics[]

The massacre was depicted in Nemesis the Warlock in 2000 AD #504 (1986).

Films[]

The massacre has been portrayed in several western movies, including Tomahawk (1951); Massacre at Sand Creek (Playhouse 90) (1956); The Guns of Fort Petticoat (1957); Soldier Blue (1970); The Last Warrior (1970); Young Guns (1988); and Last of the Dogmen (1995). The massacre is referenced by Trevor Slattery in Iron Man 3 (2013).[69]

Literature[]

- Cheyenne Autumn (1953) by Mari Sandoz;

- A Very Small Remnant (1963) by Michael Straight;

- Young Sherlock Holmes: Fire Storm by Andrew Lane, 2011;

- Centennial (1974) by James Michener;

- From Sand Creek (1981) by Simon Ortiz;

- Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1971) by Dee Brown;

- The Massacre at Sand Creek (1995) by Bruce Cutler;

- Flight (2007) by Sherman Alexie;

- Choke Creek (2009) by Lauren Small;

- Remembering the Sand Creek Massacre: A Historical Review of Methodist Involvement, Influence, and Response, by Gary L. Roberts. (2016);[70]

- There There (2018) by Tommy Orange depicts a fictionalized version of the event.

Music[]

Songs about Sand Creek include Dreadzone's "Scalplock", Gila's "Black Kettle's Ballad", Five Iron Frenzy's "Banner Year", Peter La Farge's song "The Crimson Parson", and Fabrizio De André's "Fiume Sand Creek", and J.D. Blackfoot's ballad "The Song of Crazy Horse" on that same titled LP.

Television[]

The 1978 miniseries, Centennial, includes the Sand Creek massacre as part of Episode 5, "The Massacre".[71]

The 2005 miniseries, Into the West, includes the Sand Creek massacre as part of Episode 4, "Hell on Wheels".[72]

In the episode "Old Jake" (1957) of the ABC/Desilu series, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, Francis McDonald is cast as Jake Caster, a former buffalo hunter who kills a soldier who had been a participant in the massacre and who was responsible for the slaughter of Caster's Indian wife and son; Carol Thurston plays the soldier's distraught widow, who confronts Caster.[73]

The West (1996) Season 1 Episode 4 includes the Sand Creek massacre.

Season 2, Episode 30, of the television series Tales of Wells Fargo, broadcast 3/31/1958, includes a segment on the Sand Creek Massacre aftermath, as one of the confessed commanders of the raid is led off by another officer to Fort Laramie for trial, and the Arapaho try to remove him from the stagecoach.

See also[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Gwynne, S.C., Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, Scribner, New York, 2010, p.220 ISBN 978-1-4165-9105-4

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Michno, Battle at Sand Creek, p. 241

- ^ "CONDITION OF THE INDIAN TRIBES, REPORT OF THE JOINT SPECIAL COMMITTEE, APPOINTED UNDER JOINT RESOLUTION OF MARCH 3, 1865". Senate of the United States.

- ^ Smiley, B. "Sand Creek Massacre", Archeology magazine. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ Pauls, Elizabeth Prine. "Native American". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Campbell, Jeff. "Hungate Family Murdered". National Park Service. National Park Service. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ "Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, Etc., 1851." 11 Stats. 749, Sept. 17, 1851.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Greene 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hoig 1980, p. 61.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greene 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Treaty with the Arapaho and Cheyenne, 1861" (Treaty of Fort Wise). 12 Stat. 1163, Feb. 15, 1861, p. 810.

- ^ "Sand Creek Massacre names". Cheyenne Language Web Site. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Dunn, Jacob P. Jr., Massacres of the Mountains, Harper and Bhers, New York, 1886.

- ^ Greene 2004, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hoig 1980, p. 62.

- ^ Hyde 1968, p. 118.

- ^ Moore, Craig. "Chief Lean Bear Murder". National Park Service. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Halaas, David; Masich, Andrew (March 16, 2005). Halfbreed. Da Capo Press. pp. 117–118.

- ^ Utley, Robert. Indian Frontier of the American West 1846-1890. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 89.

- ^ Howbert, Irving., "Indians of the Pike's Peak Region." The Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1914.

- ^ Dunn, William R., I Stand By Sand Creek, The Old Army Press, Colorado, 1985

- ^ Jackson, Helen (1994). A Century of Dishonor. United States: Indian Head Books. pp. 87, 343–358. ISBN 1-56619-167-X.

- ^ Evans, John., Reply to the Committee of the Conduct of the War. 6 August, 1865. The State Historical Society of Colorado.

- ^ Cahill, Kevin. "Sand Creek Massacre Fall 1864 timeline". Sand Creek Massacre Historical Website. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jackson, Helen (1994). A Century of Dishonor. United States: Indian Head Books. p. 344. ISBN 1-56619-167-X.

- ^ Brown 1970, pp. 87–88.

- ^ "Amache Prowers". Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ Nestor, Sandy (May 7, 2015). Indian Placenames in America. McFarland. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7864-9339-5.

- ^ "Jim Beckwourth". National Park Service.

- ^ Gary L. Roberts and David Fridtjof Halaas, "Written in blood", Colorado Heritage, winter 2001, pp. 22–32.

- ^ PBS (March 14, 1865). "PBS – The West". Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ Jackson, Helen (1994). A Century of Dishonor. United States: Indian Head Books. p. 345. ISBN 1-56619-167-X.

- ^ Hoig, Stan (2005) [1974]. The Sand Creek Massacre. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8061-1147-6.

- ^ Sides, Hampton (2006). Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West. New York: Doubleday. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-385-50777-6. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ Hyde 1968, pp. 154–155

- ^ Michno, Battle at Sand Creek, p.235

- ^ "Testimony of Colonel J.M. Chivington, April 26, 1865" to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. New Perspectives on the West: Documents on the Sand Creek Massacre. PBS.

- ^ Brinkley, Alan (1995). American History: a survey. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-912114-1. p. 469.

- ^ Berthrong, p. 220

- ^ Sand Creek Massacre National Historical Site quotes from his letter

- ^ Brown, 1970, p. 91.

- ^ Michno, Battle at Sand Creek

- ^ Hoig, The Sand Creek Massacre

- ^ United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1865 (testimonies and report)

- ^ Hyde 1968, pp. 156, 165

- ^ McMurtry, Larry Oh What a Slaughter!; Massacres in the American West 1846–1890, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2005 p. 103.

- ^ Hyde 1968, p. 159.

- ^ Hyde 1968, pp. 159, 162.

- ^ Hyde 1968, pp. 156–159

- ^ Greene 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Greene 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greene 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Hyde 1968, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Hyde 1968, p. 338.

- ^ Hyde 1968, Life of George Bent Written From His Letters, pp. 168–195

- ^ Page 188, The Fighting Cheyenne, George Bird Grinnell, University of Oklahoma Press (1956 original copyright 1915 Charles Scribner's Sons), hardcover, 454 pages

- ^ "United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1865 (testimonies and report)". University of Michigan Digital Library Production Service. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- ^ United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1865, Appendix page 57 (testimonies and report)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Laura King Van Dusen, Historic Tales from Park County: Parked in the Past (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2013), ISBN 978-1-62619-161-7, p. 33.

- ^ Calhoun, Patricia (March 27, 2013). "Sand Creek Massacre and John Chivington's explosive actions 151 years after Glorieta Pass". Westword. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/ntreaty/apchar65.htm

- ^ "Secretary Kempthorne Creates Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site" (Press release). U.S. Department of the Interior. April 23, 2007. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ [1] Land Saved by the American Battlefield Trust, accessed May 18, 2018.

- ^ "Trail honors victims of massacre". Independent Record. Helena, MT. Associated Press. August 16, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Calhoun, Patricia (April 25, 2013). "History Colorado could shutter its controversial Sand Creek Massacre exhibit". Westword. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ Hernandez, Elizabeth (December 3, 2014)."Gov. Hickenlooper apologizes to descendants of Sand Creek Massacre". The Denver Post. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ Verlee, Megan (December 15, 2014). "150 Years Later, A Formal Apology For The Sand Creek Massacre". NPR. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ Sand Creek Massacre Memorial website

- ^ "'Iron Man 3' Villain Invokes Sand Creek Massacre". Indian Country Today. May 7, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ https://www.umcjustice.org/who-we-are/social-principles-and-resolutions/united-methodist-responses-to-the-sand-creek-massacre-3328

- ^ "The Massacre, Centennial, November 11, 1978". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ "Hell on Wheels, Into the West, July 8, 2005". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ "Old Jake, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, April 9, 1957". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

References[]

- Official Records of the War of the Rebellion.

- Berthrong, Donald J. (1963). The Southern Cheyennes. Civilization of the American Indian. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1199-5.

- Brown, Dee (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6669-2.

- Greene, Jerome A. (2004). Washita, The Southern Cheyenne and the U.S. Army. Campaigns and Commanders, vol. 3. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3551-9.

- Hatch, Thom (2004). Black Kettle: The Cheyenne Chief Who Sought Peace but Found War. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-44592-0.

- Hoig, Stan (1977). The Sand Creek Massacre. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1147-6.

- Hoig, Stan (1980). The Peace Chiefs of the Cheyennes. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1573-3.

- Hyde, George E. (1968). Life of George Bent Written from His Letters. Ed. by Savoie Lottinville. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1577-1.

- Michno, Gregory F. (2004). Battle at Sand Creek. El Segundo, CA: Upton and Sons, Publishers. ISBN 978-0-912783-37-6.

- Michno, Gregory F. (2003). Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes 1850–1890. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-468-9.

- "Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, Etc., 1851." 11 Stats. 749, Sept. 17, 1851. In Charles J. Kappler, compiler and editor, Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties – Vol. II: Treaties. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904, pp. 594–596. Through Oklahoma State University Library, Electronic Publishing Center.

- "Treaty with the Arapaho and Cheyenne, 1861" (Treaty of Fort Wise). 12 Stat. 1163, Feb. 15, 1861. Ratified Aug. 6, 1861; proclaimed Dec. 5, 1861. In Charles J. Kappler, compiler and editor, Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties – Vol. II: Treaties. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904, pp. 807–811. Through Oklahoma State University Library, Electronic Publishing Center.

- United States Army. (1867). Courts of Inquiry, Sand Creek Massacre. Report of the Secretary of War Communicating, In Compliance With a Resolution of the Senate of February 4, 1867, a Copy of the Evidence Taken at Denver and Fort Lyon, Colorado Territory, By a Military Commission, Ordered to Inquire into the Sand Creek Massacre, November, 1864. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Senate Executive Document 26, 39th Congress, Second Session. Reproduced in Wynkoop, Christopher H. (2004-08-13). "Inquiry into the Sand Creek Massacre, November, 1864." The Wynkoop Family Research Library. Rootsweb.com: Freepages. Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- United States Congress. (1867). Condition of the Indian Tribes. Report of the Joint Special Committee Appointed Under Joint Resolution of March 3, 1865, with an Appendix. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- United States Senate. (1865). "Massacre of the Cheyenne Indians". Report of the Joint Committee on The Conduct of the War. (3 vols.) Senate Report No. 142, 38th Congress, Second Session. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. I–VI, 3–108

- West, Elliott (1998). The Contested Plains: Indians, Goldseekers, and the Rush to Colorado. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1029-7.

- Winger, Kevin (August 17, 2007). "Trail Helps Mark 1864 Massacre". Cheyenne Wyoming Tribune-Eagle.

- Jackson, Helen. (1994). A Century of Dishonor. United States: Indian Head Books. ISBN 1-56619-167-X.

Further reading[]

- Mendoza, Patrick M. With foreword by Ben Nighthorse Campbell, 1993. Song of Sorrow: Massacre at Sand Creek. Denver, CO: Willow Wind Publishing Co. ISBN 0-9636362-0-0

- Kelman, Ari (2013). A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04585-9.

- Allen, Michael (November 24, 2014). "A Massacre in the Family: My Great-Great-Grandfather and an American Indian Tragedy". Wall Street Journal.

External links[]

- Who is the Savage?

- Finding The Site

- Sand Creek Massacre Historic Site

- Sand Creek Tours

- Historic Documents from PBS, especially look up testimony from John S. Smith to Congress

- Report of the United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1865 at University of Michigan Digital Library Production Service, University of Michigan

- Sand Creek Massacre Documentary Film Project

- National Park Service CWSAC Battle Summary

- 1st Annual Sand Creek Massacre Spiritual "For the People" Healing Run, 2011 video

- Treaty Of The Little Arkansas full text

Coordinates: 38°32′51.75″N 102°30′22.86″W / 38.5477083°N 102.5063500°W

- 1864 in Colorado Territory

- Massacres of the American Civil War

- Arapaho

- Battles of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War

- Cheyenne tribe

- Colorado in the American Civil War

- Colorado Territory

- Conflicts in 1864

- Indian wars of the American Old West

- Kiowa County, Colorado

- Massacres of Native Americans

- Native American history of Colorado

- Union victories of the American Civil War

- United States military scandals

- United States war crimes

- November 1864 events

- Massacres in the United States

- Native American genocide

- Ethnic cleansing in the United States

- Battles in Colorado