Sergei Korolev

Sergei Korolyov | |

|---|---|

Сергей Королёв | |

| |

| Born | Sergey Pavlovich Korolev Сергей Павлович Королёв 12 January [O.S. 30 December 1906] 1907 |

| Died | 14 January 1966 (aged 59) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow |

| Nationality | Russian, Ukrainian[1][2][3][4][5][6] |

| Education | Kiev Polytechnic Institute, Bauman Moscow State Technical University |

| Occupation | Rocket engineer, Chief Designer of the Soviet space program |

| Spouse(s) | Ksenia Vincentini Nina Ivanovna Kotenkova[7] |

| Children | 1 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Soviet Union |

| Service/ | Red Army |

| Years of service | 1945–1952 |

| Rank | Polkovnik (colonel) |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| Soviet space program |

|---|

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev[a] or Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov (Russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, IPA: [sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf] (![]() listen); Ukrainian: Сергій Павлович Корольов, romanized: Serhij Pavlovych Korol'ov; January 12 [O.S. December 30] 1907 – 14 January 1966) was a lead Soviet rocket engineer and spacecraft designer during the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. He is regarded by many as the father of practical astronautics.[9][10] He was involved in the development of the R-7 Rocket, Sputnik 1, launching Laika, Belka and Strelka and the first human being, Yuri Gagarin, into space.[11]

listen); Ukrainian: Сергій Павлович Корольов, romanized: Serhij Pavlovych Korol'ov; January 12 [O.S. December 30] 1907 – 14 January 1966) was a lead Soviet rocket engineer and spacecraft designer during the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. He is regarded by many as the father of practical astronautics.[9][10] He was involved in the development of the R-7 Rocket, Sputnik 1, launching Laika, Belka and Strelka and the first human being, Yuri Gagarin, into space.[11]

Although Korolev trained as an aircraft designer, his greatest strengths proved to be in design integration, organization and strategic planning. Arrested on a false official charge as a "member of an anti-Soviet counter-revolutionary organization" (which would later be reduced to "saboteur of military technology"),[12] he was imprisoned in 1938 for almost six years, including some months in a Kolyma labour camp. Following his release he became a recognized rocket designer and a key figure in the development of the Soviet Intercontinental ballistic missile program. He later directed the Soviet space program and was made a Member of Soviet Academy of Sciences, overseeing the early successes of the Sputnik and Vostok projects including the first human Earth orbit mission by Yuri Gagarin on 12 April 1961. Korolev's unexpected death in 1966 interrupted implementation of his plans for a Soviet crewed Moon landing before the United States 1969 mission.

Before his death he was officially identified only as Glavny Konstruktor (Главный Конструктор), or the Chief Designer, to protect him from possible Cold War assassination attempts by the United States.[13] Even some of the cosmonauts who worked with him were unaware of his last name; he only went by Chief Designer.[11] Only following his death in 1966 was his identity revealed and he received the appropriate public recognition as the driving force behind Soviet accomplishments in space exploration during and following the International Geophysical Year.

Early life[]

Korolev was born in Zhytomyr, the capital of Volhynian Governorate of the Russian Empire. His father, Pavel Yakovlevich Korolev, was born in Mogilev to a Russian soldier and a Belarusian mother.[14][15] His mother, Maria Nikolaevna Koroleva (Moskalenko/Bulanina), was a daughter of a wealthy merchant from the Ukrainian city of Nizhyn (then part of the Russian Empire), with Zaporozhian Cossack, Greek and Polish heritage.[15][16][17]

His father moved to Zhytomyr to be a teacher of the Russian language.[18] Three years after Sergei's birth the couple separated due to financial difficulties. Although Pavel later wrote to Maria requesting a meeting with his son, Sergei was told by his mother that his father had allegedly died. Sergei never saw his father after the family break-up, and Pavel died in 1929 before his son learned the truth.

Korolev grew up in Nizhyn, under the care of his maternal grandparents Mykola Yakovych Moskalenko who was a trader of the Second Guild and Maria Matviivna Moskalenko (Fursa), a daughter of a local cossack. Korolev's mother also had a sister Anna and two brothers Yuri and Vasyl. Maria Koroleva was frequently away attending Women's higher education courses in Kiev. As a child, Korolev was stubborn, persistent, and argumentative. Sergei grew up a lonely child with few friends. Korolev began reading at an early age, and his abilities in mathematics and other subjects made him a favorite student of his teachers, but caused jealousy from his peers. He later stated in an interview, the torment of classmates bullying and teasing him as a small child encouraged his focus on academic work.[19] His mother divorced Pavel in 1915 and in 1916 married Grigory Mikhailovich Balanin, an electrical engineer who had been educated in Germany but who had to attend the Kiev Polytechnic University because German engineering diplomas were not recognized in Russia. After getting a job with the regional railway, Grigory moved the family to Odessa in 1917, where they endured hardships with many other families through the tumultuous years following the Russian Revolution and continuing internecine struggles until the Bolsheviks assumed unchallenged power in 1920. Local schools were closed and young Korolev had to continue his studies at home. Grigory proved a good influence on his step-son, who suffered from a bout of typhus during the severe food shortages of 1919.

Education[]

Korolev received vocational training in carpentry and in various academics at the Odessa Building Trades School (Stroyprofshkola No. 1). Enjoyment of a 1913 air show inspired interest in aeronautical engineering. Korolev began designing a glider as a diversion while studying for his graduation exams at the vocational school. He made an independent study of flight theory, and worked in the local glider club. A detachment of military seaplanes had been stationed in Odessa, and Korolev took a keen interest in their operations.

In 1923 he joined the Society of Aviation and Aerial Navigation of Ukraine and the Crimea (OAVUK). He had his first flying lesson after joining the Odessa hydroplane squadron and had many opportunities to fly as a passenger. In 1924 he personally designed an OAVUK construction project glider called the K-5. He briefly trained in gymnastics until his academic work suffered from this distraction. Korolev hoped to attend the Zhukovsky Academy in Moscow, but his qualifications did not meet the academy's standards.[19] He attended the Kiev Polytechnic Institute's aviation branch in 1924 while living with his uncle Yuri, and earning money to pay for his courses by performing odd jobs. His curriculum was technically oriented, and included various engineering, physics and mathematics classes. He met and became attracted to a classmate, Xenia Vincentini, who would later become his first wife.[19] In 1925 he was accepted into a limited class on glider construction, and suffered two broken ribs flying the training glider they built. He continued courses at Kiev until he was accepted into the Bauman Moscow State Technical University (MVTU, BMSTU) in July 1926.

Korolev studied specialized aviation topics until 1929, while living with his family in the typically crowded conditions of Moscow. Korolev enjoyed opportunities to fly gliders and powered aircraft during this part of his education. He designed a glider in 1928, and flew it in a competition the next year. The Communist Party accelerated the education of engineers in 1929 to meet the country's urgent need for their skills. Korolev obtained a diploma by producing a practical aircraft design by the end of the year. His advisor was the famous Andrei Tupolev.

Early career[]

After graduation, Korolev worked with some of the best Soviet designers at the 4th Experimental Section aircraft design bureau OPO-4 headed by [fr] who emigrated to the USSR from France in the 1920s.[20] He did not stand out in this group, but while so employed he also worked independently to design a glider capable of performing aerobatics. In 1930 he became interested in the possibilities of liquid-fueled rocket engines to propel airplanes while working as a lead engineer on the Tupolev TB-3 heavy bomber. Korolev earned his pilot's license in 1930 and explored the operational limits of the aircraft he piloted, wondering what was beyond his plane's altitude limit and how he could get there. Many believe this was the start of his interest in space.[19]

Korolev married Xenia Vincentini on 6 August 1931. He had first proposed marriage to her in 1924, but she then declined so she might continue her higher education. In 1931, Korolev and space travel enthusiast Friedrich Zander participated in the creation of the Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (GIRD), one of the earliest state-sponsored centers for rocket development in the USSR. In May 1932 Korolev was appointed chief of the group; and military interest encouraged funding of group projects. GIRD developed three different propulsion systems, each more successful than the last. Their first launch of a liquid-fueled rocket was GIRD-X in 1933. (Although this is often cited as the GIRD-09, the hybrid GIRD-09 used solid gasoline and liquid oxygen.)[21] This was just seventeen years after Colonel Ivan Platonovich Grave's first launch in 1916 (patent in 1924).

Growing military interest in this new technology caused GIRD to be merged with the Gas Dynamics Laboratory (GDL) at Leningrad in 1933 to create the Jet Propulsion Research Institute (RNII), headed up by the military engineer Ivan Kleimenov and containing a number of enthusiastic proponents of space travel, including Valentin Glushko. In 1932 Korolev began working on GRID-6, experimenting on the idea of Jet Fighters. The earliest models were made in the same year, only to be fully operational and doing its first manned flight in year 1940. Korolev became the Deputy Chief of the institute, where he supervised development of cruise missiles and a crewed rocket-powered glider. "Rocket Flight in Stratosphere" was published by Korolev in 1934.[citation needed]

On 10 April 1935, Korolev's wife gave birth to their daughter, Natalya; and they moved out of Sergei's parents' home and into their own apartment in 1936. Both Korolev and his wife had careers, and Sergei always spent long hours at his design office. By now he was chief engineer at RNII. The RNII team continued their development work on rocketry, with particular focus on the area of stability and control. They developed automated gyroscope stabilization systems that allowed stable flight along a programmed trajectory. Korolev was a charismatic leader who served primarily as an engineering project manager. He was a demanding, hard-working man, with a disciplinary style of management. Korolev personally monitored all key stages of the programs and paid meticulous attention to detail.[citation needed]

Imprisonment[]

Korolev was arrested by the NKVD on 27 June 1938 after being accused of deliberately slowing the work of the research institute by Ivan Kleymenov, Georgy Langemak, leaders of the institute who were executed in January,[22] and Valentin Glushko, who was arrested in March.[23] He was tortured in the Lubyanka prison to extract a confession during the Great Purge, and was tried and sentenced to death as the purge was waning;[24] Glushko and Korolev survived. Glushko and Korolev had reportedly been denounced by Andrei Kostikov, who became the head of RNII after its leadership was arrested. The rocket program fell far behind the rapid progress taking place in Nazi Germany. Kostikov was ousted a few years later over accusations of budget irregularities.[25]:17

Korolev was sent to prison, where he wrote many appeals to the authorities, including Stalin himself. Following the fall of NKVD head Nikolai Yezhov, the new chief Lavrenti Beria chose to retry Korolev on reduced charges in 1939; but by that time Korolev was on his way from prison to a Gulag camp in the far east of Siberia, where he spent several months in a gold mine in the Kolyma area before word reached him of his retrial. Work camp conditions of inadequate food, shelter, and clothing killed thousands of prisoners each month.[19] Korolev sustained injuries and lost most of his teeth from scurvy before being returned to Moscow in late 1939.[24] When he reached Moscow, Korolev's sentence was reduced to eight years[26] to be served in a sharashka penitentiary for intellectuals and the educated. These were labor camps where scientists and engineers worked on projects assigned by the Communist party leadership. The Central Design Bureau 29 (CKB-29, ЦКБ-29) of the NKVD, served as Tupolev's engineering facility, and Korolev was brought here to work for his old mentor. During World War II, this sharashka designed both the Tupolev Tu-2 bomber and the Petlyakov Pe-2 dive bomber. The group was moved several times during the war, the first time to avoid capture by advancing German forces. Korolev was moved in 1942 to the sharashka of Kazan OKB-16 under Glushko. Korolev and Glushko designed rocket-assisted take off boosters for aircraft and the RD-1 kHz[27] auxiliary rocket motor tested in an unsuccessful fast-climb Lavochkin La-7R. Korolev was isolated from his family until 27 June 1944 when he—along with Tupolev, Glushko and others—was finally discharged by special government decree, although the charges against him were not dropped until 1957.[28]

Korolev rarely talked about his experience in the Gulag. He lived under constant fear of being executed for the military secrets he possessed, and was deeply affected by his time in the camp, becoming reserved and cautious. He later learned Glushko was one of his accusers and this may have been the cause of the lifelong animosity between the two men. The design bureau was handed over from NKVD control to the government's aviation industry commission. Korolev continued working with the bureau for another year, serving as deputy designer under Glushko and studying various rocket designs.[25]:16

Ballistic missiles[]

Korolev was commissioned into the Red Army with the rank of colonel in 1945; his first decoration was the Badge of Honor, awarded in 1945 for his work on the development of rocket motors for military aircraft. On 8 September 1945, Korolev was brought to Germany along with many other experts to recover the technology of the German V-2 rocket.[29] The Soviets placed a priority on reproducing lost documentation on the V-2, and studying the various parts and captured manufacturing facilities. That work continued in East Germany until late 1946, when 2,000+ German scientists and engineers were sent to the USSR through Operation Osoaviakhim. Most of the German experts, Helmut Gröttrup being an exception, were engineers and technicians involved in wartime mass-production of V-2, and they had not worked directly with Wernher von Braun. Many of the leading German rocket scientists, including Dr. von Braun himself, surrendered to Americans and were transported to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip.[30]

Stalin made rocket and missile development a national priority upon signing a decree on 13 May 1946,[29] and a new NII-88 institute was created for that purpose in the suburbs of Moscow. Korolev's team oversaw 170+ German specialists - including Helmut Gröttrup and Fritz Karl Preikschat - in Branch 1 of NII-88 on Gorodomlya Island in Lake Seliger some 200 kilometres (120 mi) from Moscow. Their facility was surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards with watch-dogs, although Boris Chertok, chief designer of guidance and control systems, notes in his book, Rockets and People:

All structures on Gorodomlya island were renovated and living conditions were quite decent for those times. At least married specialists received separate two- or three-room apartments. Visiting the island, I could only envy them, because I and my family lived in Moscow in a shared four-room apartment, where we had two rooms of 24 square metres (260 sq ft) combined. Many of our specialists and workers lived in barracks without most elementary necessities. [...] This is why life on the island behind barbed wire could not compare at all to prisoner of war conditions.[31]

Boris Chertok Rockets and People

Development of ballistic missiles was put under the military control of Dmitriy Ustinov through the decree signed by Stalin, and Ustinov appointed Korolev as chief designer of long-range missiles at the Special Design Bureau 1 (OKB-1) of NII-88. Korolev demonstrated his organizational abilities in this new facility by keeping a dysfunctional and highly compartmentalized organization operating.[32]

With blueprints produced from disassembled V-2 rockets, the team began producing a working replica of the rocket. This was designated the R-1, and was first tested in October 1947. A total of eleven were launched with five hitting the target. This was similar to the German hit ratio, and demonstrated the unreliability of the V-2. In 1947, Korolev's group began working on more advanced designs, with improvements in range and throw weight. The R-2 doubled the range of the V-2, and was the first design to utilize a separate warhead. This was followed by the R-3, which had a range of 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi), and thus could target England. The Soviets continued to utilize the expertise of the Germans on V-2 technology for some time; but, to preserve secrecy surrounding the ballistic missile program, Gröttrup and his team had no access to classified work of their Soviet colleagues on new rocket technology including production and testing facilities. This negatively affected the morale of the German team and limited their technical contributions. The Ministry of Defence decided to dissolve the German team in 1950 and repatriated the German engineers and their families between December 1951 and November 1953.[31]

Glushko couldn't obtain the required thrust from the R-3 engines, so the project was canceled in 1952; and Korolev joined the Soviet Communist Party that year to request money from the government for future projects including the R-5, with a more modest 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) range. It completed a first successful flight by 1953. The world's first true intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) was the R-7 Semyorka. This was a two-stage rocket with a maximum payload of 5.4 tons, sufficient to carry the Soviets' bulky nuclear bomb an impressive distance of 7,000 kilometres (4,300 mi). After several test failures, the R-7 successfully launched on 21 August 1957, sending a dummy payload to the Kamchatka Peninsula. Because of Korolev's success with the R-7 and because the Soviet Union had successfully created the ICBM before the United States of America, he was nationally recognized by the Soviet Union, although his name was kept secret. However, despite the Soviet R-7 initial success, it experienced later failures as it was not intended to be a practical weapon.[29] On 19 April 1957 Korolev was declared fully "rehabilitated", as the government acknowledged that his sentence was unjust.[33]

Space program[]

Korolev was keenly aware of the orbital possibilities of the rockets being designed as ICBMs. He had brought up the idea of using the R-7 to launch a satellite into space to the Central Committee of the Communist Party on 26 May 1954, but was rejected as the Communist Party was uninterested.[29][19] Korolev's Tikhonravov group filed exaggerated Soviet newspaper articles which were referred by the United States (US) press. This influenced American authorities to start satellite programs, announced on 29 July 1955 by the Eisenhower administration. While the US government debated the idea of spending millions of dollars on this concept, Korolev's group suggested the international prestige of launching a satellite before the United States could act. Korolev sent another proposal (attached with American newspaper articles about the US program) on 5 August, and on 8 August the Soviet leadership approved Korolev's satellite project. The spirit of cold war competition was adequate to secure approval for the project.[34][35]

Sputnik 1 was designed and constructed in less than a month by the Tikhonravov group,[34] with Korolev personally managing the assembly at a hectic pace. The satellite was a simple polished metal sphere no bigger than a beach ball, containing batteries that powered a transmitter using 4 external communication antennas. Sputnik 1 was successfully completed and launched into space on 4 October 1957 using a rocket that had successfully launched only once before. It was the very first satellite of its kind.

International response to the accomplishment was electrifying, and political ramifications continued for decades. Nikita Khrushchev — initially bored with the idea of another "Korolev rocket launch" — was pleased with this success after the wide recognition, and encouraged launch of a more sophisticated satellite less than a month later, in time for the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution on 3 November.[29]

Korolev and close associate Mstislav Keldysh wished to up the ante of building a second, larger satellite by proposing the idea of putting a dog on board, which sufficiently caught the interest of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.[29] This new Sputnik 2 spacecraft had six times the mass of the Sputnik 1, and carried the dog Laika as a payload. The entire vehicle was designed from scratch within four weeks, with no time for testing or quality checks. It was successfully launched on 3 November and Laika was placed in orbit. There was no mechanism to bring the dog back to Earth; the dog died from heat exhaustion after five hours in space.[36]

The instrument-laden Sputnik 3 spacecraft was launched initially on 27 April 1958, but the satellite had a failure with the engine which caused the satellite to fall back down to earth in separate pieces.[29] On 15 May 1958, Sputnik 3 was successfully launched into orbit. The tape recorder that was to store the data failed after launch. As a result, the discovery and mapping of the Van Allen radiation belts was left to the United States' Explorer 3 and Pioneer 3 satellites. Sputnik 3 left little doubt with the American government about the Soviets' pending ICBM capability.

The Moon[]

Even before the Sputnik 1 launch, Korolev was interested in getting to the Moon. He came up with the notion to modify the R-7 missile in order to carry a package to the Moon. However, it was not until 1958 that this idea was approved, after Korolev wrote a letter explaining that his current technology would make it possible to get to the Moon.[29] A modified version of the R-7 launch vehicle was used with a new upper stage. The engine for this final stage was the first designed to be fired in outer space. Mechta is the Russian word meaning "dream", and this is the name Korolev called his moon ships. Officially, the Soviet Union called them Lunas.[29] The first three lunar probes launched in 1958 all failed in part because of political pressure forcing the launches to be rushed with an inadequate budget to test and develop the hardware properly before they were ready to fly. Korolev thought political infighting in Moscow was responsible for the lack of sufficient funding for the program, although the US space program at this early phase also had a scarcely enviable launch record. Once, when pressured to beat the US to a working lunar probe, Korolev allegedly exclaimed: "Do you think that only American rockets explode!?"[19] The Luna 1 mission on 2 January 1959 was intended to impact the surface, but missed by about 6,000 kilometres (3,700 mi). Nevertheless, this probe became the first to reach escape velocity and the first to go near the Moon, as well as becoming the first man-made object to enter the Sun's orbit.[29] A subsequent attempt (Luna E-1A No.1) failed at launch, and then Luna 2 successfully impacted the surface on 14 September 1959, giving the Soviets another first. This was followed just one month later by an even greater success with Luna 3. It was launched only two years after Sputnik 1, and on 7 October 1959 was the first spacecraft to photograph the far side of the Moon, which was something the people of earth had never seen beforehand.[29]

The Luna missions were intended to make a successful soft landing on the Moon, but Korolev was unable to see a success. Luna 4 and Luna 6 both missed, Luna 5, Luna 7, and Luna 8 all crashed on the Moon. It was not until after Korolev's death that the Soviet Union successfully achieved a soft landing on the Moon with the Luna 9.[29]

Towards the latter part of Korolev's life, he had been working on projects for reaching the planets Mars and Venus, and even had spacecraft ready to reach both. The United States was also working towards reaching these planets, so it was a race to see who would be successful. Korolev's two initial Mars probes suffered from engine failures, and the five probes the Soviet Union launched in hopes of reaching Venus all failed between 1961 and 1962, Korolev himself supervised the launches of all probes.[29]

On 1 November 1962, the Soviet Union successfully launched the Mars 1 and although communications failed, was the very first to complete a flyby of Mars. Later, the Soviet Union launched Venera 3, which was the very first impact of Venus. It was not until after Korolev's death that the Soviet Union impacted Mars.[29]

Korolev's group was also working on ambitious programs for missions to Mars and Venus, putting a man in orbit, launching communication, spy and weather satellites, and making a soft-landing on the Moon. A radio communication center needed to be built in the Crimea, near Simferopol and near Evpatoria to control the spacecraft. Many of these projects were not realized in his lifetime, and none of the planetary probes performed a completely successful mission until after his death.

Human spaceflight[]

Although he was having ideas since 1948, Korolev's planning for the piloted mission began in 1958 with design studies for the future Vostok spacecraft. It was to hold a single passenger in a space suit, and be fully automated. The space suit, unlike the United States' pure oxygen system, was 80 percent nitrogen and only 20 percent oxygen.[29] The capsule had an escape mechanism for problems prior to launch, and a soft-landing and ejection system during the recovery. The spacecraft was spherical, just like the Sputnik design, and Korolev explained his reasoning for this by saying "the spherical shape would be more stable dynamically".[29] Beginning with work on the Vostok, Konstantin Feoktistov was recruited directly by Korolev to be the principal designer for crewed spaceflight vehicles.[29]

On 15 May 1960 an uncrewed prototype performed 64 orbits of the Earth, but the reentry maneuver failed. On 28 July 1960, two dogs by the names of Chaika and Lishichka were launched into space, but the mission was unsuccessful when an explosion killed the dogs. However, on 19 August, the Soviet Union became the first to successfully recover living creatures back to Earth. The dogs, Belka and Strelka were successfully launched into space on a Vostok spacecraft and they completed eighteen orbits.[29] Following this, the Soviet Union sent a total of six dogs into space, two in pairs, and two paired with a dummy. Unfortunately, not all the missions were successful. After gaining approval from the government, a modified version of Korolev's R-7 was used to launch Yuri Alexeevich Gagarin into orbit on 12 April 1961, which was before the United States was able to put Alan Shepard into space.[29] Korolev served as capsule coordinator, and was able to speak to Gagarin who was inside the capsule. The first human in space and Earth orbit returned to Earth via a parachute after ejecting at an altitude of 7 kilometres (23,000 ft). Gagarin was followed by additional Vostok flights, culminating with 81 orbits completed by Vostok 5 and the launch of Valentina Tereshkova as the first woman cosmonaut in space aboard Vostok 6.

Korolev proposed communications satellites and a modified Vostok useful for photographic reconnaissance to quiet Soviet military objections about the cost of planetary and crewed programs of no perceived value for national defense. Korolev planned to move forward with Soyuz craft able to dock with other craft in orbit and exchange crews. He was directed by Khrushchev to cheaply produce more 'firsts' for the piloted program, including a multi-crewed flight. Korolev was reported to have resisted the idea as the Vostok was a one-man spacecraft and the three-man Soyuz was several years away from being able to fly. Khrushchev was not interested in technical excuses and let it be known that if Korolev could not do it, he would give the work to his rival, Vladimir Chelomei.

Cosmonaut Alexei Leonov describes the authority Korolev commanded at this time.[13]

Long before we met him, one man dominated much of our conversation in the early days of our training; Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, the mastermind behind the Soviet space program. He was only ever referred to by the initials of his first two names, SP, or by the mysterious title of "Chief Designer", or simply "Chief". For those on the space program there was no authority higher. Korolev had the reputation of being a man of the highest integrity, but also of being extremely demanding. Everyone around him was on tenterhooks, afraid of making a wrong move and invoking his wrath. He was treated like a god.

Leonov recalls the first meeting between Korolev and the cosmonauts.[37]

I was looking out of the window when he arrived, stepping out of a black Zis 110 limousine. He was taller than average;

I could not see his face, but he had a short neck and large head. He wore the collar of his dark-blue overcoat turned up and the brim of his hat pulled down.

"Sit down, my little eagles," he said as he strode into the room where we were waiting.

He glanced down a list of our names and called on us in alphabetical order to introduce ourselves briefly and talk about our flying careers.

The Voskhod was designed as an incremental improvement on the Vostok to meet Khruschev's goal. As a single capsule would be ineffective for proper travel to the Moon, the vehicle needed to be able to hold more people.[29] Khrushchev ordered Korolev to launch three people on the Voskhod capsule quickly, as the United States had already completed a two-man mission with Gemini. Korolev accepted, on the condition that more backing would be given to his N-1 rocket program.[29] One of the difficulties in the design of the Voskhod was the need to land it via parachute. The three-person crew could not bail out and land by parachute, since the altitude would not be survivable. So the craft would need much larger parachutes in order to land safely. Early tests with the craft resulted in some failures causing the death of test animals until use of stronger fabric improved parachute reliability.

The resulting Voskhod was a stripped-down vehicle from which any excess weight had been removed; although a backup retrofire engine was added, since the more powerful Voskhod rocket used to launch the craft would send it to a higher orbit than the Vostok, eliminating the possibility of a natural decay of the orbit and reentry in case of primary retrorocket failure. After one uncrewed test flight, this spacecraft carried a crew of three cosmonauts, Komarov, Yegorov and Feoktistov, into space on 12 October 1964 and completed sixteen orbits. This craft was designed to perform a soft landing, eliminating a need for the ejection system; but the crew was sent into orbit without space suits or a launch abort system.

With the Americans planning a space walk with their Gemini program, the Soviets decided to trump them again by performing a space walk on the second Voskhod launch. After rapidly adding an airlock, the Voskhod 2 was launched on 18 March 1965, and Alexei Leonov performed the world's first space walk. The flight very nearly ended in disaster, as Leonov was just barely able to re-enter through the airlock, and plans for further Voskhod missions were shelved. In the meantime the change of Soviet leadership with the fall of Khrushchev meant that Korolev was back in favor and given charge of beating the US to landing a man on the Moon.

For the Moon race, Korolev's staff started to design the immense N1 rocket in 1961,[38] using the NK-15 liquid fuel rocket engine.[39] He also was working on the design for the Soyuz spacecraft that was intended to carry crews to LEO and to the Moon. As well, Korolev was designing the Luna series of vehicles that would soft-land on the Moon and make robotic missions to Mars and Venus. Unexpectedly, he died in January 1966, before he could see his various plans brought to fruition.

Criticism[]

Engineer Sergei Khrushchev, son of former Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, explained in an interview some shortcomings of Korolev's approach, which in his opinion is why the Soviets didn't land on the Moon:

I think Russia had no chance to be ahead of the Americans under Sergei Korolev and his successor, Vasili Mishin. ... Korolev was not a scientist, not a designer: he was a brilliant manager. Korolev's problem was his mentality. His intent was to somehow use the launcher he had [the N1 (rocket)]. It was designed in 1958 for a different purpose and with a limited payload of about 70 tons. His philosophy was, let's not work by stages [as is usual in spacecraft design], but let's assemble everything and then try it. And at last it will work. There were several attempts and failures with Lunnik [a series of uncrewed Soviet moon probes]. Sending man to the moon is too complicated, too complex for such an approach. I think it was doomed from the very beginning.

— Saswato R. Das, "The Moon Landing through Soviet Eyes: A Q&A with Sergei Khrushchev, son of former premier Nikita Khrushchev: A son of the Cold War tells what it was like from the losing side of the Space Race—and how the U.S.S.R.'s space program fizzled after Sputnik and Gagarin" [1], Scientific American (16 July 2009)

Another reason the program didn't succeed was the rivalry between Korolev and Vladimir Chelomey. Their animosity was due to the intolerable persona of both men, and their desire for leadership at any cost. The two never said a harsh word about each other either in public or in private, but toppled each other's projects in any way possible. Instead of dividing competencies and responsibilities and cooperating in order to pursue the same goal, the two struggled for leadership in the space program.[40] According to Khrushchev, who worked for Chelomey and knew both men well, they both would have preferred the Americans to land on the Moon first rather than their rival.[41]

Death[]

On 3 December 1960, Korolev suffered his first heart attack. During his convalescence, it was also discovered that he was suffering from a kidney disorder, a condition brought on by his detention in the Soviet prison camps. He was warned by the doctors that if he continued to work as intensely as he had, he would not live long. Korolev became convinced that Khrushchev was only interested in the space program for its propaganda value and feared that he would cancel it entirely if the Soviets started losing their leadership to the United States, so he continued to push himself.

By 1962, Korolev's health problems were beginning to accumulate and he was suffering from numerous ailments. He had a bout of intestinal bleeding that led to him being taken to the hospital in an ambulance. In 1964 doctors diagnosed him with cardiac arrhythmia. In February he spent ten days in the hospital after a heart problem. Shortly after he was suffering from inflammation of his gallbladder. The mounting pressure of his workload was also taking a heavy toll, and he was suffering from a lot of fatigue. Korolev was also experiencing hearing loss, possibly from repeated exposure to loud rocket-engine tests.

The actual circumstances of Korolev's death remain somewhat uncertain. In December 1965, he was supposedly diagnosed with a bleeding polyp in his large intestine. He entered the hospital on 5 January 1966 for somewhat routine surgery, but died nine days later. It was stated by the government that he had what turned out to be a large, cancerous tumor in his abdomen, but Glushko later reported that he actually died due to a poorly performed operation for hemorrhoids. Another version states that the operation was going well and no one was predicting any complications. Suddenly, during the operation, Korolev started to bleed. Doctors tried to provide intubation to allow him to breathe freely, but his jaws, injured during his time in a Gulag, had not healed properly and impeded the installation of the breathing tube. Korolev died without regaining consciousness. According to Harford, Korolev's family confirmed the cancer story. His weak heart contributed to his death during surgery.[42]

Under a policy initiated by Stalin and continued by his successors, the identity of Korolev was not revealed until after his death. The purported reason was to protect him from foreign agents from the United States. As a result, the Soviet people didn't become aware of his accomplishments until after his death. His obituary was published in the Pravda newspaper on 16 January 1966, showing a photograph of Korolev with all his medals. Korolev's ashes were interred with state honors in the Kremlin Wall.

Korolev is often compared to Wernher von Braun as the leading architect of the Space Race.[43] Like von Braun, Korolev had to compete continually with rivals, such as Vladimir Chelomei, who had their own plans for flights to the Moon. Unlike the Americans, he also had to work with technology that in many aspects was less advanced than what was available in the United States, particularly in electronics and computers, and to cope with extreme political pressure.

Korolev's successor in the Soviet space program was Vasily Mishin, a quite competent engineer who had served as his deputy and right-hand man. After Korolev died, Mishin became the Chief Designer, and he inherited what turned out to be a flawed N1 rocket program. In 1972, Mishin was fired and then replaced by a rival, Valentin Glushko, after all four N-1 test launches failed. By that time, the rival Americans had already made it to the Moon, and so the program was canceled by CPSU General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev.

Personal life[]

The Soviet émigré Leonid Vladimirov related the following description of Korolev by Glushko at about this time:

Short of stature, heavily built, with head sitting awkwardly on his body, with brown eyes glistening with intelligence, he was a skeptic, a cynic and a pessimist who took the gloomiest view of the future. 'We are all going to be whacked and there will be no obituary' (Khlopnut bez nekrologa, Хлопнут без некролога – i.e. "we will all vanish without a trace") was his favorite expression.[44]

Korolev was rarely known to drink alcoholic beverages, and chose to live a fairly austere lifestyle.[citation needed]

His career also contributed to instability in his personal life. About 1946, the marriage of Korolev and Vincentini began to break up. Vincentini was heavily occupied with her own career, and about this time Korolev had an affair with a younger woman named Nina Ivanovna Kotenkova, who was an English interpreter in the Podlipki office.[19] Vincentini, who still loved Korolev and was angry over the infidelity, divorced him in 1948. Korolev and Kotenkova were married in 1949, but he is known to have had affairs even after this second marriage.

Korolev's passion for his work was a characteristic that made him a great leader. He was committed to training younger engineers to move into his space and missile projects, even while consumed with his own work. Korolev knew that students would be the future of space exploration, which is why he made such an effort to communicate with them.[19] Arkady Ostashev was one of Korolev's students, who Korolev hired to do dissertation work before later becoming an engineer and working on the R-2.[29]

Awards and honours[]

Korolev, ultimately, will be remembered for the new genre of science and innovation management, a program manager, an idea that was not fully understood or realized till 1990s. Korolev, an engineer by training, was able to navigate unpredictable and dangerous Soviet politics of Moscow, secure funding and support of leadership to the cause that was only vaguely defined ( space exploration), create shared vision to sell the idea to an extended set of disparate stakeholders, created an entirely new segment of science and, finally, delivered a concrete value that defied imaginations. This genre of the program management and its ability to make profound impact, found parallels and support in 90's Silicon valley where Korolev enjoys cult following and remains an inspiration as the "startup CEO"

Among his awards, Korolev was twice honored as Hero of Socialist Labour, in 1956 and 1961. He was also a Lenin Prize winner in 1971,[45] and was awarded the Order of Lenin three times, the Order of the Badge of Honour and the Medal "For Labour Valour".

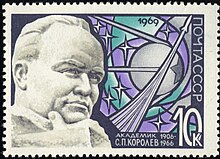

In 1958 he was elected to the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. In 1969 and 1986, the USSR issued 10 kopek postage stamps honoring Korolev.[46] In addition he was made an Honorary Citizen of Korolyov and received the Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow".

Sergei Khrushchev claimed that the Nobel Prize committee attempted to award Korolev but the award was turned down by Khrushchev in order to maintain harmony within the Council of Chief Designers.[47]

In 1990, Korolev was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.[48]

Namesakes[]

A street in Moscow was named after Korolev in 1966 and is now called Ulitsa Akademika Korolyova (Academician Korolyov Street). The memorial home-museum of akademician S.P.Korolyov was established in 1975 in the house where Korolev lived from 1959 till 1966 (Moscow, 6th Ostankinsky Lane,2/28).[49] In 1976 he was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame.[45]

The town of Kaliningrad (formerly Podlipki, Moscow region) is the home of RSC Energia, the largest space company in Russia. In 1996, Boris Yeltsin renamed the town after Korolyov. There is now an oversized statue of Korolev located in the town square. RSC Energia was also renamed to S.P. Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation Energia.

Astronomical features named after Korolev include the crater Korolev on the far side of the Moon, a crater on Mars, and the asteroid 1855 Korolyov.

Quite a large number of streets exist with his name in Russia as well as in Ukraine. In Zhytomyr on the other side of the street (vulytsia Dmytrivska) from the house where Korolev was born is the Korolev Memorial Astronautical Museum.

A visual phenomenon iconic to a type of rocket staging event is named the Korolev cross in honor of Korolev.

Aeroflot named a brand new Boeing 777 named after Korolev in 2021.

Portrayals in fiction[]

The first portrayal of Korolev in Soviet cinema was made in the 1972 film Taming of the Fire, in which Korolev was played by Kirill Lavrov.

He was played by in the 2005 BBC co-produced docudrama Space Race.

In 2011 the British writer Rona Munro produced the play Little Eagles on Korolev's life – its premiere was from 16 April to 7 May 2011, in an RSC production at the Hampstead Theatre,[50] with Korolev played by Darrel D'Silva and Yuri Gagarin by Dyfan Dwyfor.[51][52]

He was played by Mikhail Filippov in the 2013 Russian film Gagarin: First in Space.

He was portrayed by Vladimir Ilyin in the 2017 Russian film The Age of Pioneers.

"Korolev" is the name and subject of a track by Public Service Broadcasting.

Korolev appeared briefly in a film-within-a-film in The Right Stuff during the administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower, inside one of the President's conference rooms.

Korolev opens the 2007 graphic novel Laika by Nick Abadzis.

Korolev plays a major role in the 2009 graphic novel T-Minus: The Race to The Moon by Zander Cannon, Jim Ottaviani and Kevin Cannon

The science fiction novel by Paolo Aresi titled Korolev was published in the Italian magazine series Urania in April 2011.

The story The Chief Designer by Andy Duncan is a fictionalized account of Korolev's career.

The Russian 304 class ship in Stargate SG-1 was named after Korolev.

The character of Aleksandr Leonovitch Granin in the video game Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is Inspired by Korolev.

In Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, a United Federation of Planets Starfleet Constitution-class ship and a class of Starfleet ships are named after Korolev.

Korolev's death is discussed by Jack Ryan and Simon Harding in the 2002 spy novel, Red Rabbit.

According to Ronald D. Moore, the creator of the alternate history TV series For All Mankind, the divergence point of the alternate timeline was that Korolev instead survives the surgery in 1966, which leads to the Soviets landing on the moon first.

Korolev city is the name of the fictional human colony on Mars in the Brazilian sci-fi novel Crônicas do Cretáceo (The Cretaceous Chronicles), published in 2020.

See also[]

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ "Sergei Korolev: Father of the Soviet Union's success in space", European Space Agency, 3 September 2007

"Sergei Pavlovich Korolyov was the son of a teacher of Russian literature, he was born on 12 January 1907 in Zhytomyr, Ukraine." - ^ Minkel, JR (5 October 2007), "Sputnik Hype Launched One-Sided Space Race", Scientific American

"Sputnik was the brainchild of a group of Russian engineers, led by Chief Designer Sergei Korolev..." - ^ Wade, Mark, "Korolev, Sergei Pavlovich", www.astronautix.com

"Nation: Russia, Ukraine". - ^ Golovanov, Yaroslav Kirillovich (1994). Королёв: Факты и мифы [Korolev: Facts and Myths]. Nauka. p. 111. ISBN 5-02-000822-2.

- ^ Pacner, Karel (31 March 2018), "Utajený sovětský hrdina: Raketový konstruktér Sergej Koroljov (1.)" [Secret Soviet Hero: Rocket Designer Sergei Korolyov (part 1)], 100+1

"Sergei Pavlovich Korolev was born on January 12, 1907 in Zhytomyr" - ^ Syruček, Milan (January 2008). Na prahu atomové války: Svět mohl být mnohokrát zničen, aniž to tušil [On the threshold of nuclear war: The world could have been destroyed many times without realizing it] (in Czech). Epocha. ISBN 978-80-87027-86-8.

- ^ Harford, p. 25, 94.

- ^ Harford 1997, p. xvi.

- ^ Авг 02, 2011 Новый этап в технологиях теплозащитных покрытий На заводе введён в эксплуатацию специализированный производственный участок и введение в эксплуатацию современный автоклавный комплекс . Участок и оборудование предназначены для производства из композиционных материалов теплозащитных покрытий космичес��их кораблей и различных изделий ракетно-космической техники. tr. "Aug 02, 2011 A new stage in the technology of heat-protective coatings. A specialized production site was commissioned at the plant and a modern autoclave complex was commissioned. The site and equipment are intended for the production of heat-shielding coatings for spacecraft and various products of rocket and space technology from composite materials." Archived 15 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine energia-zem.ru

- ^ Sagdeyev, R. Z.; Shtern, M. I. "The Conquest of Outer Space in the USSR 1974". NASA. NASA Technical Reports Server. hdl:2060/19770010175.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b West, John B. (1 October 2001). "Historical aspects of the early Soviet/ Russian crewed space program". Journal of Applied Physiology. 91 (4): 1501–1511. doi:10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1501. PMID 11568130.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2000). Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945–1974. NASA. p. 12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scott and Leonov, p. 53. Harford, p. 135.

- ^ Королев Павел Яковлевич 1877-1929, отец С.П. Королева tr. "Korolev Pavel Yakovlevich 1877-1929, father of S.P. Koroleva" (Source: Koroleva N.S., 2002) www.famhist.ru, accessed 18 April 2021

- ^ Jump up to: a b Наталия Королева – С.П. Королев Отец, Москва Наука, 2007, accessed 18 April 2021

- ^ 1. Биография Сергея Королева, астропортреты родителей и отчима. tr. "1. Biography of Sergei Korolev, astro-portraits of parents and stepfather. " Буралков А.А., Астрология, 2011, № 1, 52-59, accessed 18 April 2021

- ^ Наталия Королева – С.П. Королев Отец, page 19, Москва Наука, 2007

- ^ В Житомире сто лет назад появился на свет Сергей Королев. ФОТО / Культура / Журнал Житомира / Zhitomir City Journal. tr. "Sergey Korolev was born in Zhitomir a hundred years ago" Zhzh.info (12 January 2007). Retrieved on 30 April 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Harford, James. Korolev: How One Man Masterminded the Soviet Drive to Beat America to the Moon. New York: Wiley, 1999. Print.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (26 February 2010). The red rockets' glare. Spaceflight and the Soviet imagination, 1857–1957. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-521-89760-0.

- ^ Altman and Holzman (2007). "1, Overview and History of Hybrid Rocket Propulsion". In Martin J. Chiaverini; Kenneth K. Kuo (eds.). Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics, vol. 218: Fundamentals of Hybrid Rocket Propulsion. Reston, VA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. p. 5.

- ^ Albrecht, Ulrich; Nikutta, Randolph (1993). The Soviet Armaments Industry. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers. p. 76. ISBN 978-3-7186-5313-3.

- ^ French, Francis; Burgess, Colin (2007). Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961-196. University of Nebraska Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780803206977.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Korolev vs Von Braun: The Space Race

- ^ Jump up to: a b Siddiqi, Asif A. (2000). Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974. NASA SP-2000-4408. Washington, DC: NASA.

- ^ French, Francis; Colin Burgess; Paul Haney (2007). Into that Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961–1965. University of Nebraska Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8032-1146-9.

- ^ "Last of the Wartime Lavochkins", AIR International, Bromley, Kent, U.K., November 1976, Volume 11, Number 5, pages 245–246.

- ^ Parrish, Michael (1996). The Lesser Terror. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 46. ISBN 0-275-95113-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Harford, James (1999). Korolev : how one man masterminded the Soviet drive to beat America to the moon. Wiley. ISBN 0471327212. OCLC 60196908.

- ^ "Sputnik Biographies--Sergei P. Korolev (1906-1966)". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Черток Б.Е., Ракеты и люди (Boris Chertok, Rockets and People)

- ^ Brzezinski, Matthew (2007). Red Moon Rising. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-8147-3.

- ^ "Sergei Korolev: Father of the Soviet Union's success in space". www.esa.int. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sputnik remembered: The first race to space (part 1) (page 1)". www.thespacereview.com. The Space Review. 2 October 2017. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

To add power to his request, he added a folder containing a bunch of recent articles from the American media, all properly translated, all communicating that the United States was giving priority to its own satellite program. The attached folder clinched the deal: a little over a week after the American announcement, on August 8, 1955, the Soviet Politburo approved a satellite project under Korolev

- ^ "Sixty Years Later, Sputnik Declassifications Offer Primer in Fake News". Fordham Newsroom. Fordham University. 10 October 2017.

"In 1954 . . . because they knew a lot of Soviet journalists, they flooded the Soviet media with speculative articles on space flight .. cited a lot in the Washington Post and New York Times. July 1955, the Eisenhower administration announces they're going to launch a satellite in a couple of years, it's going to be a scientific satellite

- ^ "Sputnik-2 in orbit", Russian Space Web, accessed 18 April 2021

- ^ Scott and Leonov, p. 54.

- ^ Lindroos, Marcus. The Soviet manned Lunar program MIT. Accessed: 4 October 2011.

- ^ Wade, Mark (2015). "NK-15". Encyclopedia Astronautix. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Khrushchev, Sergei (2010). Никита Хрущев: Рождение сверхдержавы [Nikita Khrushchev: The Birth of a Superpower] (in Russian). Moscow: Vremya. pp. 210–225, 245–291, 553–576.

- ^ Sergei Khrushchev talks to Echo Moskvy (in Russian).

- ^ McKie, Robin, "Sergei Korolev: the rocket genius behind Yuri Gagarin", The Observer, 13 March 2011, retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Lillian Cunningham (13 August 2019). "Inside the Gulag". Moonrise. Episode 13. 39 minutes minutes in. Washington Post Podcasts.

- ^ Kerber, Lev. Tupolev's Sharaga — 1973 (in Russian).

- ^ Jump up to: a b International Space Hall of Fame :: New Mexico Museum of Space History :: Inductee Profile nmspacemuseum.org

- ^ Image of 1969, 10k stamp. Image of 1986, 10k stamp.

- ^ Air and Space Magazine airspacemag.com

- ^ Sprekelmeyer, Linda, editor. These We Honor: The International Aerospace Hall of Fame. Donning Co. Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57864-397-4.

- ^ "The memorial home-museum of akademician S.P.Korolev". Archived from the original on 13 March 2005. Retrieved 6 February 2005.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ What's On Main Stage Archived 21 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Hampstead Theatre. Retrieved on 30 April 2011.

- ^ Cast and creatives – Little Eagles Archived 25 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine. RSC. Retrieved on 30 April 2011.

- ^ Billington, Michael (21 April 2011). "Little Eagles – review". The Guardian.

Bibliography[]

- Harford, James (1999). Korolev: How One Man Masterminded the Soviet Drive to Beat America to the Moon. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-14853-9. NASA segments

- Korolyov, S. P. (1934). Rocket Flight in the Stratosphere. Moscow: State Military Publishers (Гос. воен. изд.). (bibrec (in Russian)[permanent dead link])

- Korolyov, S. P. (1957). The Practical Significance of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky's Proposals in the Field of Rocketry. Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences.

- Mishin, Vassily P. (12 November 1991). "Why Didn't We Fly to the Moon?". JPRS-Usp-91-006: 10.

- Scott, David; Alexei Leonov (2006). Two Sides of the Moon: Our Story of the Cold War Space Race. with . St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-30866-3.

- Vladimirov, Leonid (1971). The Russian Space Bluff. David Floyd (trans.). The Dial Press. ISBN 0-85468-023-3.

- "Rockets and people" – B. E. Chertok, M: "mechanical engineering", 1999. ISBN 5-217-02942-0 (in Russian)

- Georgiy Stepanovich Vetrov, S. P. Korolyov and space. First steps. — 1994 M. Nauka, ISBN 5-02-000214-3.

- "Testing of rocket and space technology – the business of my life" Events and facts – A.I. Ostashev, Korolev, 2001.[2];

- "Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries that Ignited the Space Age", – Matthew Brzezinski, Henry Holt and Company, 2008 г. ISBN 080508858X;

- A.I. Ostashev, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov – The Genius of the 20th Century — 2010 M. of Public Educational Institution of Higher Professional Training MGUL ISBN 978-5-8135-0510-2.

- Bank of the Universe – edited by Boltenko A. C., Kyiv, 2014., publishing house "Phoenix", ISBN 978-966-136-169-9

- S. P. Korolev. Encyclopedia of life and creativity – edited by C. A. Lopota, RSC Energia. S. P. Korolev, 2014 ISBN 978-5-906674-04-3

- "We grew hearts in Baikonur" – Author: Eliseev V. I. M: publisher OAO MPK in 2018, ISBN 978-5-8493-0415-1

- "Space science city Korolev" – Author: Posamentir R. D. M: publisher SP Struchenevsky O. V., ISBN 978-5-905234-12-5

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sergei Korolyov. |

- Episode 47 of astrotalkuk.org Contains recording from the unveiling of Yuri Gagarin Statue event in London on 14 July 2011, includes Natalya Koroleva speaking about her father.

- Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (1907–1966) Biography, with several historic photographs provided by Natalya Koroleva.

- "Korolev, Mastermind of the Soviet Space Program" Biography, with a few photographs, by James Harford, adapted, in part, from the author's book.

- "Sergei Pavlovich Korolev" Biography by Phil Delnon dated May 1998.

- "Sergey P. Korolev. The Great Engineer and Scientist". Biography at the official website of Korolev, Moscow Oblast

- The official website of the city administration Baikonur – Honorary citizens of Baikonur

- Soviet and Russian space programmes

- PBS Red Files

- Korolev — detailed biography at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- Detailed biography at Centennial of Flight website

- Korolëv's slide rule at the U.S. National Air and Space Museum. His German-made slide rule was a "magician's wand" to his colleagues.

- Photograph and description of monument to S. Korolev at the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute.

- Extensive collection of photographs and documents related to Korolev at the RGANTD (РГАНТД) (in Russian)

- Family history

- Korolev as a boy in Nizhyn, 1912.

- Korolev as a student at KPI, 1924.

- (RGANTD is the Russian State Archive for Scientific and Technical Documentation.)

- Sergei Korolev

- 1907 births

- 1966 deaths

- 20th-century Russian engineers

- Aviation inventors

- Baikonur Cosmodrome

- Bauman Moscow State Technical University alumni

- Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union members

- Early spaceflight scientists

- Employees of RSC Energia

- Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- Glider pilots

- Gulag detainees

- Heroes of Socialist Labour

- Kyiv Polytechnic Institute alumni

- Lenin Prize winners

- Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology faculty

- People from Zhytomyr

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin

- Rocket scientists

- Russian aerospace engineers

- Russian people of Belarusian descent

- Russian people of Greek descent

- Russian people of Polish descent

- Russian people of Ukrainian descent

- Sharashka inmates

- Soviet aerospace engineers

- Soviet rehabilitations

- Soviet space program personnel

- Ukrainian Cossacks

- Ukrainian people of Belarusian descent

- Ukrainian people of Greek descent

- Ukrainian people of Polish descent

- Ukrainian people of Russian descent