Sex, Lies, and Videotape

| Sex, Lies, and Videotape | |

|---|---|

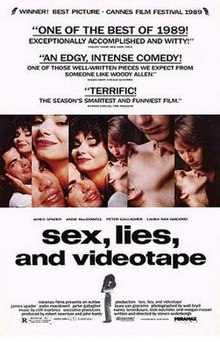

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Soderbergh |

| Written by | Steven Soderbergh |

| Produced by | John Hardy Robert Newmyer |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Walt Lloyd |

| Edited by | Steven Soderbergh |

| Music by | Cliff Martinez |

Production company | Outlaw Productions |

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.2 million |

| Box office | $36.7 million[2] |

Sex, Lies, and Videotape is a 1989 American independent drama film written and directed by Steven Soderbergh. The plot tells the story of a troubled man who videotapes women discussing their sexuality and fantasies, and his impact on the relationships of a troubled married couple and the wife's younger sister.

Sex, Lies, and Videotape won the Palme d'Or at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, making Soderbergh the youngest solo director to win the award; he was 26 at the time. The film was influential in revolutionizing the independent film movement in the early 1990s. In 2006, Sex, Lies, and Videotape was added to the United States Library of Congress' National Film Registry, deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot[]

Ann Bishop Mullany lives in Baton Rouge, unhappily but comfortably married to John, a successful lawyer. She is in therapy, where she reveals that she is repulsed by the idea of John touching her. Graham Dalton, an old close college friend of John and now a drifter with some money saved up, visits Baton Rouge to see John and perhaps stay in the city. Graham meets Ann when he arrives at their home, who learns that John has invited Graham to stay with them until he finds an apartment. When John arrives home, Graham's demeanor becomes remarkably more guarded; though he realizes he now has nothing in common with John, he and Ann get along well.

John is having an affair with Ann's sister Cynthia, a free-spirited artist and bartender, which he rationalizes by blaming Ann's frigidity. Ann helps Graham look for an apartment. After Graham finds a place, Ann makes an impromptu visit and notices stacks of camcorder videotapes, labeled with women's names. When pressed, Graham explains that they contain interviews with women about their sexual experiences and fantasies. Offended and confused, Ann abruptly leaves.

The next day, Cynthia appears uninvited at Graham's apartment and presses Graham to explain what "spooked" Ann. Graham reluctantly explains the videotapes and admits to Cynthia that he is impotent when in the presence of a woman. Instead, he achieves gratification by watching the videos in private. Graham propositions Cynthia to make an interview tape, assuring her that only he will see them. She agrees, and later tells Ann about the experience. Ann is horrified, as is John when Cynthia later tells him.

Cleaning her home the next day, Ann discovers Cynthia's pearl earring in her bedroom while vacuuming, and deduces her affair with John. Furious, Ann goes to Graham's apartment with the intention of making a videotape. Graham objects, but she is insistent.

Later, Ann demands a divorce from John, and reveals that she made a tape with Graham. John rushes to Graham's apartment and, after attacking Graham and locking him out, watches Ann's tape. In the video, Ann says she has never felt any kind of "satisfaction" from sex. After Graham asks if she ever thinks of having sex with other men, she admits she has thought of Graham. Ann turns the camera on Graham, who resists opening up, but soon confesses that he is haunted by his ex-girlfriend Elizabeth, and that his motivation in returning to Baton Rouge was an attempt to achieve some closure. Graham explains that he was a pathological liar, which destroyed an otherwise rewarding relationship with Elizabeth. He has since gone to great lengths to keep people at a distance and avoid relationships. Ann kisses Graham, then turns off the camcorder, ending the tape.

A chastened John joins Graham on the front porch and, with obvious pleasure, confesses to having sex with Elizabeth while she and Graham were a couple, saying "She was no saint. She was good in bed, and she could keep a secret. That's all I can say about her." After he leaves, Graham angrily destroys his camcorder and all of the videotapes.

The next day, John is summoned to his boss's office, where it's implied that he is about to be fired. Ann and Cynthia reconcile at the bar Cynthia tends, before Ann goes to Graham's and joins him on the front porch.

Cast[]

- James Spader as Graham Dalton

- Andie MacDowell as Ann Bishop Mullany

- Peter Gallagher as John Mullany

- Laura San Giacomo as Cynthia Patrice Bishop

- Steven Brill as Barfly

- Ron Vawter as Therapist

Production[]

The film was written by Steven Soderbergh in eight days on a yellow legal pad during a cross country trip (although, as Soderbergh points out in his DVD commentary track, he had been thinking about the film for a year).

Soderbergh's commentary also reveals that he had written Andie MacDowell's role with Elizabeth McGovern in mind, but McGovern's agent disliked the script so much that McGovern never even got to read it. Laura San Giacomo, who was represented by the same agency, had to threaten to leave that agency in order to be able to play Cynthia. Soderbergh was reluctant to audition MacDowell but she surprised him, getting the role after two extremely successful auditions. The role of John would have been played by Tim Daly, but delays in completing the financing for the film led to Peter Gallagher's getting the role instead.

With a budget of only $1.2 million, a week of rehearsal and a month-long shoot in August 1988 was all Soderbergh could afford. He would later call it “the only movie I’ve ever made where I felt like I had all the money and all the time I needed.”[3] Principal photography took place in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.[4]

Reception[]

Box office[]

Sex, Lies, and Videotape opened in a limited release on August 4, 1989, in 4 theaters and grossed $155,982, with an average of 30 patrons per showing in the first 2-3 weeks; the studio released the film nationwide. The widest release for the film was 534 theaters and it ended up earning $24,741,667 in the United States,[5] and around $36.74 million worldwide.[2]

Critical response[]

Sex, Lies, and Videotape was well received in its initial release in 1989 and holds a "certified fresh" rating of 96% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 51 reviews with an average score of 8.00/10. The consensus states "In his feature directorial debut, Steven Soderbergh demonstrates a mastery of his craft well beyond his years, pulling together an outstanding cast and an intelligent script for a nuanced, mature film about neurosis and human sexuality."[6] The film also has a score of 86 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 17 reviews indicating 'universal acclaim'.[7]

In 2006, Sex, Lies, and Videotape was selected and preserved by the United States National Film Registry as being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Accolades[]

At the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, the film won the Palme d'Or and the FIPRESCI Prize, with Spader getting the Best Actor Award.[8] It also won an Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival. Soderbergh was nominated for an Academy Award for his screenplay.

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | March 26, 1990 | Best Original Screenplay | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | [9] |

| British Academy Film Awards | March 11, 1990 | Best Original Screenplay | Nominated | [10] | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Laura San Giacomo | Nominated | |||

| Cannes Film Festival | May 11–23, 1989 | Palme d'Or | Steven Soderbergh | Won | [8] |

| FIPRESCI Prize | Won | ||||

| Best Actor | James Spader | Won | |||

| César Awards | March 4, 1990 | Best Foreign Film | Steven Soderbergh | Nominated | [11] |

| Golden Globe Awards | January 20, 1990 | Best Screenplay | Nominated | [12] | |

| Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Andie MacDowell | Nominated | |||

| Best Supporting Actress | Laura San Giacomo | Nominated | |||

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association | December 16, 1989 | Best Actress | Andie MacDowell | Won | [13] |

| New Generation Award | Laura San Giacomo | Won | |||

| National Board of Review | December 13, 1989 | Top Ten Films | Won | [14] | |

| Sundance Film Festival | 1989 | Audience Award | Steven Soderbergh | Won | [15] |

| Writers Guild of America | 1989 | Best Screenplay | Nominated | [16] |

Home media[]

The DVD includes a "director's dialogue" between Soderbergh and playwright/director Neil LaBute, recorded in 1998. LaBute's presence leads to conversational tangents unrelated to the film, although most of the tangents are related to the question of what it means to be a director, and are intended, as Soderbergh summarizes at the end, to "demystify" the process of making a film. LaBute's presence prompts Soderbergh to talk about reverse zooms, dolly shots, how actors have varying expectations of their director, the difference between stealing from a film you admire and paying tribute to it, shooting out of sequence, how the role of a director changes as their success (and their budgets) grow, and other filmmaking topics.

Adaptations[]

The movie was presented as a staged play in Hollywood at the Next Stage from December 13, 2003 to January 17, 2004. Directed by Seth Wiley and a cast that featured Amanda Bauman (Ann), Emily Williams (Therapist), Shauna Slade (Cynthia), Justin Christenson (Graham), and Jack Sundmacher (John).[17]

"An unofficial sequel of sorts"[]

A sequel was announced in 2001 and Catherine Keener was the first actor attached to the project, named How to Survive a Hotel Room Fire. It was billed by Miramax as "an unofficial sequel of sorts."[18] In October it was announced the movie would star Julia Roberts, David Hyde Pierce, and David Duchovny. After the September 11 attacks, the title was changed to The Art of Negotiating a Turn.[19] Miramax head Harvey Weinstein did not like the new title, and consequently Soderbergh suggested the title, Full Frontal, under which the film was released.[20]

References[]

- ^ "Sex, Lies, and Videotape (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 1989-08-07. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ "How 'sex, lies, and videotape' Changed Indie Filmmaking Forever". 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ "'Sex, Lies, and Videotape': Steven Soderbergh's Groundbreaking Debut that Shook the Indie Filmmaking Scene • Cinephilia & Beyond". 23 April 2017. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ "sex, lies and videotape (1989)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ "Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "sex, lies, and videotape Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Festival de Cannes: Sex, Lies, and Videotape". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "The 62nd Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "Film in 1990". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "Palmarès 1990 - 15 Ème Cérémonie Des César". Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "Sex, Lies, and Videotape". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "15th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "1989 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "How Steven Soderbergh's 'sex, lies and videotape' Still Influences Sundance After 25 Years". IndieWire. 15 January 2014. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (25 February 1990). "Oscar Is Sometimes a Grouch". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Kendt, Rob (2003-01-08). "Sex, Lies, And Videotape". Backstage. Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ "Casting under way for sex, lies and videotape sequel | Film". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ "Film Entitled How To Survive A Hotel Room Fire May Be Changed - Hotel Business". 3 October 2001. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ Elvis Mitchell (2002-07-28). "FILM; Sketching, For a Change, On Screen - The New York Times". Nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

External links[]

- Sex, Lies, and Videotape at IMDb

- Sex, Lies, and Videotape at the TCM Movie Database

- Sex, Lies, and Videotape at Box Office Mojo

- Sex, Lies, and Videotape at Rotten Tomatoes

- Sex, Lies, and Videotape at Metacritic

- sex, lies, and videotape: Some Kind of Skin Flick an essay by Amy Taubin at the Criterion Collection

- 1989 films

- English-language films

- 1989 drama films

- Adultery in films

- American films

- American drama films

- American independent films

- Films directed by Steven Soderbergh

- Films set in Louisiana

- Films shot in Louisiana

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Film winners

- Palme d'Or winners

- Sundance Film Festival award winners

- United States National Film Registry films

- Films scored by Cliff Martinez

- Films with screenplays by Steven Soderbergh

- 1989 independent films

- 1989 directorial debut films