Sexagenary cycle

| Sexagenary cycle | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 六十干支 | ||

| |||

| Stems-and-Branches | |||

| Chinese | 干支 | ||

| |||

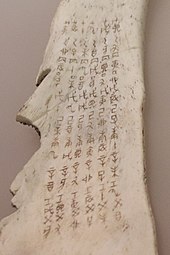

The sexagenary cycle, also known as the Stems-and-Branches or ganzhi (Chinese: 干支), is a cycle of sixty terms, each corresponding to one year, thus a total of sixty years for one cycle, historically used for recording time in China and the rest of the East Asian cultural sphere.[1] It appears as a means of recording days in the first Chinese written texts, the Shang oracle bones of the late second millennium BC. Its use to record years began around the middle of the 3rd century BC.[2] The cycle and its variations have been an important part of the traditional calendrical systems in Chinese-influenced Asian states and territories, particularly those of Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, with the old Chinese system still in use in Taiwan, and to a lesser extent, in Mainland China.[3]

This traditional method of numbering days and years no longer has any significant role in modern Chinese time-keeping or the official calendar. However, the sexagenary cycle is used in the names of many historical events, such as the Chinese Xinhai Revolution, the Japanese Boshin War, the Korean Imjin War and the Vietnamese Tet Mau Than. It also continues to have a role in contemporary Chinese astrology and fortune telling. There are some parallels in this with the current 60-year cycle of the Hindu calendar.

Overview[]

Each term in the sexagenary cycle consists of two Chinese characters, the first being one of the ten Heavenly Stems of the Shang-era week and the second being one of the twelve Earthly Branches representing the years of Jupiter's duodecennial orbital cycle. The first term jiǎzǐ (甲子) combines the first heavenly stem with the first earthly branch. The second term yǐchǒu (乙丑) combines the second stem with the second branch. This pattern continues until both cycles conclude simultaneously with guǐhài (癸亥), after which it begins again at jiǎzǐ. This termination at ten and twelve's least common multiple leaves half of the combinations—such as jiǎchǒu (甲丑)—unused; this is traditionally explained by reference to pairing the stems and branches according to their yin and yang properties.

This combination of two sub-cycles to generate a larger cycle and its use to record time have parallels in other calendrical systems, notably the Akan calendar.[4]

History[]

The sexagenary cycle is attested as a method of recording days from the earliest written records in China, records of divination on oracle bones, beginning ca. 1250 BC. Almost every oracle bone inscription includes a date in this format. This use of the cycle for days is attested throughout the Zhou dynasty and remained common into the Han period for all documentary purposes that required dates specified to the day.

Almost all the dates in the Spring and Autumn Annals, a chronological list of events from 722 to 481 BC, use this system in combination with regnal years and months (lunations) to record dates. Eclipses recorded in the Annals demonstrate that continuity in the sexagenary day-count was unbroken from that period onwards. It is likely that this unbroken continuity went back still further to the first appearance of the sexagenary cycle during the Shang period.[5]

The use of the sexagenary cycle for recording years is much more recent. The earliest discovered documents showing this usage are among the silk manuscripts recovered from Mawangdui tomb 3, sealed in 168 BC. In one of these documents, a sexagenary grid diagram is annotated in three places to mark notable events. For example, the first year of the reign of Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇), 246 BC, is noted on the diagram next to the position of the 60-cycle term yǐ-mǎo (乙卯, 52 of 60), corresponding to that year.[6] [7] Use of the cycle to record years became widespread for administrative time-keeping during the Western Han dynasty (202 BC – 8 AD). The count of years has continued uninterrupted ever since:[8] the year 1984 began the present cycle (a 甲子—jiǎ-zǐ year), and 2044 will begin another. Note that in China the new year, when the sexagenary count increments, is not January 1, but rather the lunar new year of the traditional Chinese calendar. For example, the ji-chou 己丑 year (coinciding roughly with 2009) began on January 26, 2009. (However, for astrology, the year begins with the first solar term "Lìchūn" (立春), which occurs near February 4.)

In Japan, according to Nihon shoki, the calendar was transmitted to Japan in 553. But it was not until the Suiko era that the calendar was used for politics. The year 604, when the Japanese officially adopted the Chinese calendar, was the first year of the cycle.[9]

The Korean (환갑; 還甲 hwangap) and Japanese tradition (還暦 kanreki) of celebrating the 60th birthday (literally 'return of calendar') reflects the influence of the sexagenary cycle as a count of years.[10]

The Tibetan calendar also counts years using a 60-year cycle based on 12 animals and 5 elements, but while the first year of the Chinese cycle is always the year of the Wood Rat, the first year of the Tibetan cycle is the year of the Fire Rabbit (丁卯—dīng-mǎo, year 4 on the Chinese cycle).[11]

Ten Heavenly Stems[]

| No. | Heavenly Stem |

Chinese name |

Japanese name |

Korean name |

Vietnamese name |

Yin Yang | Wu Xing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin (Pinyin) |

Cantonese (Jyutping) |

Middle Chinese (Baxter) |

Old Chinese (Baxter–Sagart) |

Onyomi | Kunyomi with corresponding kanji |

Romanized | Hangul | |||||

| 1 | 甲 | jiǎ | gaap3 | kæp | *[k]ˤr[a]p | kō (こう) | kinoe (木の兄) | gap | 갑 | giáp | yang | wood |

| 2 | 乙 | yǐ | jyut3 | ʔit | *qrət | otsu (おつ) | kinoto (木の弟) | eul | 을 | ất | yin | |

| 3 | 丙 | bǐng | bing2 | pjængX | *praŋʔ | hei (へい) | hinoe (火の兄) | byeong | 병 | bính | yang | fire |

| 4 | 丁 | dīng | ding1 | teng | *tˤeŋ | tei (てい) | hinoto (火の弟) | jeong | 정 | đinh | yin | |

| 5 | 戊 | wù | mou6 | muwH | *m(r)uʔ-s (~ *m(r)uʔ) | bo (ぼ) | tsuchinoe (土の兄) | mu | 무 | mậu | yang | earth |

| 6 | 己 | jǐ | gei2 | kiX | *k(r)əʔ | ki (き) | tsuchinoto (土の弟) | gi | 기 | kỷ | yin | |

| 7 | 庚 | gēng | gang1 | kæng | *kˤraŋ | kō (こう) | kanoe (金の兄) | gyeong | 경 | canh | yang | metal |

| 8 | 辛 | xīn | san1 | sin | *si[n] | shin (しん) | kanoto (金の弟) | sin | 신 | tân | yin | |

| 9 | 壬 | rén | jam4 | nyim | *n[ə]m | jin (じん) | mizunoe (水の兄) | im | 임 | nhâm | yang | water |

| 10 | 癸 | guǐ | gwai3 | kjwijX | *kʷijʔ | ki (き) | mizunoto (水の弟) | gye | 계 | quý | yin | |

Twelve Earthly Branches[]

| No. | Earthly Branch |

Chinese name |

Japanese name |

Korean name |

Vietnamese name |

Vietnamese zodiac |

Chinese zodiac |

Corresponding hours | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin (Pinyin) |

Cantonese (Jyutping) |

Middle Chinese (Baxter) |

Old Chinese (Baxter–Sagart) |

Onyomi | Kunyomi | Romanized | Hangul | ||||||

| 1 | 子 | zǐ | zi2 | tsiX | *[ts]əʔ | shi (し) | ne (ね) | ja | 자 | tý | Rat (chuột | ||