Shantinatha

| Shantinatha | |

|---|---|

Image of Tirthankara Shantinatha (Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, 12th century) | |

| Venerated in | Jainism |

| Predecessor | Dharmanatha |

| Successor | Kunthunatha |

| Symbol | Deer or Antelope |

| Height | 40 bows (120 metres) (393.701 feet) |

| Age | over 700,000 years |

| Color | Golden |

| Personal information | |

| Born | |

| Died | |

| Parents |

|

| Spouse | Yashomati |

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}} or {{transl}} (or {{IPA}} or similar for phonetic transcriptions), with an appropriate ISO 639 code. (September 2021) |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

|

Shantinatha was the sixteenth Jain tirthankar of the present age (Avasarpini).[2] Shantinatha was born to King Vishvasena and Queen Aiira at Hastinapur in the Ikshvaku dynasty. His birth date is the thirteenth day of the Jyest Krishna month of the Indian calendar. He was also a Chakravartin and a Kamadeva. He ascended to the throne when he was 25 years old.[3] After over 25,000 years at the throne, he became a Jain monk and started his penance. According to Jain beliefs, he became a siddha, a liberated soul which has destroyed all of its karma.

Biography in Jain tradition[]

Shantinatha was the sixteenth Jain Tīrthankara of the 24 tirthankars of the present age (avasarpini).[2]

Life before renunciation[]

He was born to King Vishvasena and Queen Achira at Hastinapur on 13th day of Jestha Krishna in the Ikshvaku clan.[3] Before the birth of Shantinatha, Queen Achira dreamt the sixteen most auspicious dreams.[4] Shantinatha spent 25,000 years as a youth (kumāra kāla) and married a beautiful princess.[4][5] He ruled his kingdom for 50,000 years.[6] During his rule, armoury was blessed with divine chakraratna. During his reign he conquered all six divisions of earth in all directions, acquiring elephants, horses, nine-fold most precious treasures and fourteen ratna (jewels). Shantinatha became the fifth Chakravartin.[7][5]

During his time, an epidemic of epilepsy broke out and he helped to control it.[5] Shantinath became the idea of peace and tranquility by averting epidemics, fire, famine, foreign invasions, robbers, etc., giving him the name of Shantinath. He is also associated with special right[clarification needed] known as Shantikarma.[8] According to Acharya Hemachandra, epidemics, evils and misery were destroyed when Shantinatha was in his mother's womb.[9]

Renunciation[]

Shantinatha, when made aware of his previous incarnations, renounced his worldly life and became a Jain ascetic.[7] After his sixteen year of asceticism, on the ninth bright day of the month of Pausha (December–January), he achieved kevala jnana (omniscience) under a nandi tree.[3] According to Jain texts, Shantinatha neither slept nor ate during his penance. After achieving kevala jnana he visited Somanasapur, and was offered first ahara food by King Dharma Mitra and his wife.[10]

He is said to have lived 1 lakh (100,000) years and spent many years spreading his knowledge. On the 13th day of the dark half of the month Jyestha (May–June), he attained nirvana at Sammed Shikharji,[3][7][note 1] known contemporaneously as the Parasnath Hills in northern Jharkhand.[13]

The yaksha and yakshi of Shantinatha are Kimpurusha and Mahamanasi according to Digambara tradition and Garuda and Nirvani according to Śvētāmbara tradition.[8]

Previous births[]

- King Srisena

- Yugalika in Uttar Kurukshetra

- Deva in Saudharma heaven

- Amitateja, prince of Arkakirti

- Heavenly deva in 10th heaven Pranat (20 sagars[definition needed] life span)

- Aparajit Baldeva in East Mahavideha (life span of 84,00, 000 purva[definition needed])

- Heavenly Indra in 12th heaven Achyuta (22 sagars life span)

- Vajrayudh Chakri, the son of Tirthankar Kshemanakar in East Mahvideha

- Heavenly deva in Navgraivayak heaven

- Megharath, the son of Dhanarath in East Mahavideh in the area where Simandhar Swami is moving at present

- Heavenly deva in Sarvartha Siddha Heaven (33 sagars life span)

Disciples[]

According to Jain texts, Cakrayudha Svami was the leader of the Shantinatha disciples.[7][9]

Legacy[]

Worship[]

Along with Rishabhanatha, Neminatha, Parshvanatha and Mahavira, Shantinatha is one of the five tirthankars who attract the most devotional worship among the Jains.[8][14] According to Santistava compiled by Acharya Manadevasuri, the head of Shvetambar in the third century, mere recitation of Shantinath negates all bad omens, brings peace and protects devotees from problems.[15] Santistava is considered[by whom?] one of the four most beautifully written stavans.[definition needed][16] The Laghnu-Shantistavaa, compiled by Acharya Manadevisuri in the seventh century, is a hymn to Shantinatha full of tantric usage. The yakshi Nirvani devi is also known as Shanti-devi and prayed to with Shantinatha for peace.[8]

Literature[]

- The Shantinatha Charitra, by Acharya Ajitprabhasuri, describes the life of the 16th Jain tirthankara Shantinatha. This text is the oldest example of miniature painting and has been declared as a global treasure by UNESCO.[17]

- Shantipurana, written around the 10th century by Sri Ponna, is considered to be one of the three gems of Kannada literature.[18][19]

- Santyastaka is a hymn in praise of Śāntinātha composed by Acharya Pujyapada in the fifth century.[20]

- Ajitasanti, compiled by Nandisena in the seventh century, praises Shantinatha and Ajitnatha.[21][8]

- Santikara was compiled by Munisundarasuri in the 15th century.[22]

- Mahapurusha Charitra, compiled by Merutunga in the 13th–14th centuries, talks about Shantinatha.[23]

Iconography[]

Shantinatha is usually depicted in a sitting or standing meditative posture with the symbol of a deer or antelope beneath him.[24][25] Every tīrthankara has a distinguishing emblem that allows worshippers to distinguish similar-looking idols of the tirthankaras.[26][27][28] The deer or antelope emblem of Shantinath is usually carved below the legs of the tirthankara. Like all tirthankaras, Shantinath is depicted with Shrivatsa[note 2] and downcast eyes.[29]

Shantinatha idol inside Pakbirra Jain temple

Shantinath Shwetambar Jain temple, Hastinapur

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, 12th century

Main idol of Shantinatha Shri Semliya Tirth

Honolulu Academy of Arts, 15th century

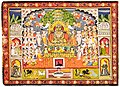

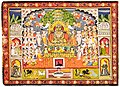

Miniature painting of Shantinatha surrounded by ascetics, devotees and animals, 18th century

Famous temples[]

- Shantinatha Temple, Khajuraho – a UNESCO World Heritage site

- Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur – birthplace of Shantinatha

- Shantinath Temple, Deogarh

- Shantinatha Basadi, Jinanathapura

- Shantinath Jain Teerth

- Shantinatha temple, Halebidu – tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage Site

- Aharji Jain Teerth

- Shantinath Jain temple, Kothara

- Odegal basadi

- Shantinath Jain Temple in Leicester (first Jain temple in Europe and the western world); see Jainism in the United Kingdom[30]

Kanch Mandir, Indore

'Singh Dwaar' of Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur

Shantinath Jain temple, Ramtek

Shringar Chori, Chittor Fort

Colossal statues[]

- In 2016, the tallest statue of Shantinatha, with a height of 54 feet (16 m), was erected in Ajmer[31]

- The 32-foot (9.8 m) statue of Shantinath at Shantinath Jinalaya, Shri Mahavirji

- The 31-foot (9.4 m) statue of Shantinath at Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur

- The 30-foot (9.1 m) image at Aggalayya Gutta, Warangal[32]

- The 22.5-foot (6.9 m) statue of Shantinath at Bhojpur Jain Temple

- The 18-foot (5.5 m) idol at Aharji

- The 18-foot (5.5 m) sculpture at Shantinatha basadi, Halebidu[33]

- The 17.5-foot (5.3 m) statue in Naugaza Digambar Jain temple[34]

- The 15-foot (4.6 m) image at Shantinatha temple, Khajuraho[35]

- The 15-foot (4.6 m) image inside Shantinath Basadi, Chandragiri

- The 12.2-foot (3.7 m) statue in Bahuriband, built in the 12th century[36]

Shantinath Jinalaya, Shri Mahavirji

Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur

Bhojpur Jain Temple

Shantinatha basadi, Halebidu

Shantinath Basadi, Chandragiri

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shantinatha. |

- God in Jainism

- Arihant (Jainism)

- Jainism and non-creationism

Notes[]

- ^ Some texts refer to the place as Mount Sammeta.[11] This place is revered in Jainism because 20 out of 24 Jinas died here.[12]

- ^ A special symbol that marks the chest of a Tirthankara. The yoga pose is very common in Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. Each tradition has had a distinctive auspicious chest mark that allows devotees to identify a meditating statue to symbolic icon for their theology. There are several srivasta found in ancient and medieval Jain art works, and these are not found on Buddhist or Hindu art works.

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Tandon 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tukol 1980, p. 31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Jain 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johnson 1931.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mittal 2006, p. 689.

- ^ Jain 2015, p. 198.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Jain 2015, p. 199.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Shah 1987, p. 152.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shah 1987, p. 151.

- ^ Art and Culture & Raja Dharma Mitra offering food to Tirthankara Shantinatha.

- ^ Jacobi 1964, p. 275.

- ^ Cort 2010, pp. 130–133.

- ^ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 13.

- ^ Cort 2010, p. 215.

- ^ Cort 2001, p. 198.

- ^ Kelting 2001, p. 96.

- ^ Shāntinātha Charitra, UNESCO.

- ^ Das 2005, p. 143.

- ^ Rice 1982, p. 30.

- ^ Jain 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Cort 2001, p. 236.

- ^ Cort 2001, p. 197.

- ^ Dalal 2014, p. 791.

- ^ Doniger 1999, p. 550.

- ^ Dalal 2010, p. 369.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Krishna 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 225.

- ^ Moore 1977, p. 138.

- ^ Wilson & Ravat 2017, p. 23.

- ^ Tiwari 2016.

- ^ The New Indian Express 2019.

- ^ ASI & Shantinatha Basti, Halebid.

- ^ Neelkanth.

- ^ Javid & Javeed 2008, p. 209.

- ^ Cunningham 1879, p. 40.

Sources[]

- Johnson, Helen M. (1931), Shantinathacaritra (Book 5 of the Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra), Baroda Oriental Institute

- Tukol, T. K. (1980). Compendium of Jainism (PDF). Dharwad: University of Karnataka.

- Shantinatha Purana.

- Shantinatha Charitra (PDF).

- Jain, Arun Kumar (2009), Faith & Philosophy of Jainism, Gyan Publishing House, ISBN 9788178357232, retrieved 8 October 2017

- Tandon, Om Prakash (2002) [1968], Jaina Shrines in India (1 ed.), New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, ISBN 9788123024547

- Mittal, J.P. (2006), History Of Ancient India From 4250 BC To 637 AD, 2, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 9788126906161

- Jacobi, Hermann (1964), Max Muller (The Sacred Books of the East Series, Volume XXII) (ed.), Jaina Sutras (Translation), Motilal Banarsidass (Original: Oxford University Press)

- Cort, John E. (2010), Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: (Jaina iconography), 1, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 9788170172086

- Krishna, Nanditha (2014), Sacred Animals of India, Penguin UK, ISBN 9788184751826

- Dalal, Roshen (2010), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin Books India, ISBN 9780143415176

- Britannica Tirthankar Definition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, ISBN 0-87779-044-2

- Moore, Albert C. (1977), Iconography of Religions: An Introduction, Chris Robertson, ISBN 9780800604882

- Wilson, Tom; Ravat, Riaz (2017). Learning to Live Well Together: Case Studies in Interfaith Diversity. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 9781784504670.

- INTERNATIONAL MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER - Shāntinātha Charitra (PDF), UNESCO

- Das, Sisir Kumar (2005), A History of Indian Literature, 500-1399: From Courtly to the Popular, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 9788126021710

- Javid, Ali; Javeed, Tabassum (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. Algora. ISBN 978-0-87586-482-2.

- "Shantinatha Basti, Halebid". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1879), Archaeological Survey of India: Reports 1862-1884, Government Press, retrieved 1 June 2017

- "Neelkanth". Archaeological Survey of India.

- Jain, Vijay K. (2015), Acarya Samantabhadra's Svayambhustotra: Adoration of The Twenty-four Tirthankara, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788190363976,

Non-Copyright

- Cort, John E. (2001), Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198030379

- Kelting, M. Whitney (2001), Singing to the Jinas: Jain Laywomen, Mandal Singing, and the Negotiations of Jain Devotion, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198032113

- "Raja Dharma Mitra offering food to Tirthankara Shantinatha". artsandculture.google.com.

- Dalal, Roshen (2014), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin UK, ISBN 9788184753967

- Jain, Vijay K. (2014), Acarya Pujyapada's Istopadesa – The Golden Discourse, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788190363969

- Rice, E. P. (1982) [first published 1921], Kannada Literature, New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-0063-0

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph (ed.), Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6CS1 maint: location (link)

- Tiwari, Raktim (16 June 2016). "Ajmer will have tallest Jain statue". Rajasthan Patrika.

- "1,000-year-old Aggalayya Gutta in Warangal to open for tourists soon", The New Indian Express, 8 July 2019

- Tirthankaras