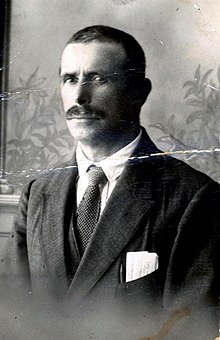

Shmuel Cohen

Samuel (Shmuel) Cohen (1870-1940) was the composer of the Israeli national anthem, the "Hatikvah" - "The Hope".

Cohen was born in 1870, in a small town near Ungheni, Moldavia, then part of the Russian Empire. Motivated by a rising tide of Russian state-sponsored antisemitism and terrorism (pogroms), Cohen emigrated to Ottoman Palestine in 1887. He idealistically settled in Rishon LeZion ("First to Zion") as part of the Hovevei Zion ("Lovers of Zion") movement. Rishon LeZion was established in 1882, as a Jewish agricultural cooperative on barren, empty land which was purchased from two brothers, Musa and Mustafa el Dagani.

In Rishon LeZion, Cohen married Minya Papirmeister and made there his living as a vintner. Cohen was an accomplished local violinist. He was given the nickname “Stempenu”, after the famous fictional klezmer violinist created by Jewish humorist and folklorist, Shalom Aleichem, in his book of the same name. In 1938, when Cohen wrote his biography, he titled it Stempenu.

Cohen was one of the founders of the first Keren Kayemet in Rishon LeZion in 1889. It predated the later national Keren Kayemet Le Yisrael, (Jewish National Fund for Israel).[1]

Cohen returned to Moldavia where he established a girls school in the early years of the 20th century. The school was not successful. He returned to Rishon LeZion, reestablishing himself as a vintner and settling permanently to raise his only child, Ida. Cohen was active in early Jewish settlement efforts in Palestine. He helped found the city of Rehovot. The effort was unique in that it did not involve financial support from Baron Edmond James de Rothschild. Philosophically, he joined with others working for the Redemption of the Ancient Land of Israel.[2][3]

Naftali Herz Imber's poem "Tikvatenu" (Our Hope), published in 1886, stirred Jews everywhere, especially those who lived under antisemitic oppression. Cohen's brother had emigrated to Ottoman Palestine, settling in c. 1883 in Yesud HaMa'ala, the first modern Jewish community and moshava in the Hula Valley. He sent a copy of Imber's poem to Cohen in Moldavia. Cohen too was inspired. The poem contributed to his decision to leave Moldavia for Palestine.

For a short period, Imber lived in Rishon LeZion. He recited his poem to eager ears. Cohen, observing the emotional response of the local Jewish farmers to Imber's poem, used his musical skill to put the poem to music. Cohen's musical composition was an adaptation of a Moldavian/Romanian folk-song, "Carul cu boi" ("The Ox Cart"). The catalyst of Cohen's musical adaptation facilitated the quick, enthusiastic spread of Imber's poem throughout all the Zionist communities of Palestine. Within a short few years, it spread globally to pro-Zionist communities and organizations becoming the unofficial Zionist anthem. It was not until 1933, at the in Prague, that the Imber-Cohen Zionist anthem became formally adopted and renamed "Hatikvah" ("The Hope").

The Hatikvah widely permeated Jewish popular culture, promoted by famous singers such as the American Al Jolson.[4]

In the succeeding years of the Holocaust (1933-1945), the Hatikvah resonated throughout the Jewish world. To the astonishment of Nazis in the death camps, the Hatikvah was sung even outside the gas chambers.[5] The British military made the most famous recording of the Hatikvah, when it was sung by survivors of the Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp.[6] The Holocaust survivors onboard the famed American rescue ship, the SS Exodus, sang the Hatikvah as it pulled into the port of Haifa.[7] The British arrested he Holocaust survivors and returned them to Germany for reinternment in DP camps.[2]"מוזאון ראשון לציון – מוזאון לתולדות ראשון לציון". www.rishonlezion-museum.org.il. Retrieved 25 May 2020.</ref>[3]

British Mandate authorities banned the singing or musical broadcasting of the Hatikvah, as it was considered provocative. A similar piece, Smetana's The Moldau, with its musical refrains reminiscent of Cohen's Hatikvah composition, was substituted for broadcast media by Zionist communities in Palestine. May 14, 1948, the Hatikvah was played at the conclusion of the Israeli Declaration of Independence ceremony. November 2004, Imber-Cohen's Hatikvah was formally adopted through Israel's Flag, Coat-of-Arms, and National Anthem Law.

Israeli children learn Naphtali Imber's poem in public school without an appreciation of Samuel Cohen’s contribution. Globally, the Hatikvah is universally recognized by Cohen’s music and not by Imber’s poem.

Death[]

Cohen died March 28, 1940. He was buried in the (Old) Rishon LeZion Cemetery. After years of neglect, Cohen's gravesite has seriously deteriorated. November 2020, the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation restored and preserved Cohen and his wife Mina's gravesites per agreement with Rishon LeZion to reflect the original historic internment style.

An interpretive, identifying element was added to help locate the internment. The element is a sculpted flame with a Star of David emerging from the middle. A musical clef is welded to the Star. The sculpture is titled after the historical meaning of the Hatikvah, the "Hope" of the Jewish people to settle peacefully again in their 2,000-year-old homeland. The sculpture was created by noted Israeli sculptor Sam Philipe. Philipe chose to construct the Flame from metal fragments of Kassem Rockets fired from the Gaza Strip in random efforts to kill Israelis. The sculpted element is titled "The Flame of the Hatikvah".

References[]

- ^ "Our History". Keren Kayemet Le Yisrael/Jewish National Fund (KKL/JNF). Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "מוזאון ראשון לציון – מוזאון לתולדות ראשון לציון" (in Hebrew). Rishon LeZion Museum. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yona Shapira, curator, Rishon LeZion Museum

- ^ Owen Nicholson (16 June 2017). "Al Jolson, Hatikvah". Youtube. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "The History of Hatikvah". 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Hatikva at Bergen-Belsen". Youtube. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Exodus 1947: History in the Making".

- "Hatikvah: Conceptions, Receptions and Reflections | המרכז לחקר המוסיקה היהודית". www.jewish-music.huji.ac.il. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Latest Updates". ReformJudaism.org. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- [Obituary Samuel Cohen, Haboker Palestine Newspaper, April 14, 1940]

- [1]

- [Biography Samuel Cohen, November 1938, (Hebrew) published in the Bustanei, (the Farmers of the Land of Israel), Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem.]

External links[]

- "The Second Death of Shmuel Cohen, the Hatikvah's Composer".

- "Encyclopedia Judaica: Ha-Tikvah". Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Samuel Cohen and "Hatikvah"". walkerhomeschoolblog. 23 January 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Hatikvah, the National Anthem of Israel". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Hatikva - National Anthem of the State of Israel". knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Zion, Ilan Ben. "How an unwieldy romantic poem and a Romanian folk song combined to produce 'Hatikva'". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- 1870 births

- 1940 deaths

- 20th-century violinists

- 20th-century composers

- Hovevei Zion

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the Ottoman Empire