Sidney Finkelstein

Sidney Finkelstein | |

|---|---|

| Born | Sidney Walter Finkelstein July 4, 1909 Brooklyn, New York, USA |

| Died | January 14, 1974 (aged 64) Brooklyn, New York, USA |

| Occupation | writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | City College of New York, New York University |

| Alma mater | Columbia University |

| Genre | Music |

| Subject | Jazz |

| Notable works | Jazz, A People's Music (1948), How Music Expresses Ideas (1952) |

| Years active | 1930s-1973 |

| Website | |

| scua | |

Sidney Finkelstein (1909-1974) was an writer of music who specialized in jazz and was best known for his books Jazz, A People's Music (1948) and How Music Expresses Ideas (1952).[1] Along Charles Seeger (father of Pete Seeger), Finkelstein is considered "one of two American Marxist musical theoreticians of consequence."[2][3] He has also been compared to British jazz writer "Francis Newton," pseudonym for British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawn.[4]

Background[]

Sidney Walter Finkelstein was born on July 4, 1909, in Brooklyn, New York. In 1929, he received a BA from the City College of New York. In 1932, he received an MA from Columbia University. (In 1955, he received a second MA from New York University.)[1][3]

Career[]

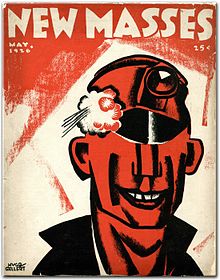

In the 1930s, Finkelstein was a book reviewer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle while also working for the United States Postal Service. In the 1940s, he joined staff of the New York Herald Tribune as a music reviewer, while also contributing to publications including the New Masses and its successor Masses and Mainstream (where he remained until its close in 1963[5]).[1][3]

In 1951, Finkelstein joined the staff of Vanguard Records, a New York record label for in jazz and classical music, where he worked until 1973.[1][3]

Finkelstein, "a former newspaper writer turned Marxist art critic,"[2] was an active member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), serving as the Party's musical and cultural theoretician. He applied Socialist Realism in his books.[1]

Investigation[]

In 1957, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) subpoenaed Finkelstein for testimony and cited his Communist party affiliation.[1] In its subsequent report, HUAC specifically identified him as "cultural spokesman for the Communist Party" and was a member of the board of directors of the Metropolitan Music School of New York City, which HUAC claimed was "controlled by identified Communists." The school's founder and director, Lilly Popper, refused to answer questions about Party affiliation. Mildred Roth accompanied Finkelstein as legal counsel. Finkelstein said he had been a board member 1955-1957 and had previously taught at the school. He would not disclose where else he had taught (specifically the Jefferson School of Social Science). He refused to comment about affiliation with the CPUSA or on HUAC's repeated questions about "communist conspiracy." With regard to conspiracy against the Nation [sic], Finkelstein retorted, "The Nation might be reduced to the terrible procedure of having to jail people for crimes only if it found that they actually committed them or found that they did something criminal, not just thinking." HUAC cited the Jefferson School as a subversive according to the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations of 2 January 1957.[6]

Immediately following his testimony, Finkelstein's name appeared in three issues of the anti-communist newsletter Counterattack as a member of the board of directors of the Metropolitan Music School.[7] In 1964, The Weekly Crusader noted the HUAC findings and commented:

...on October 2, 1920, Lenin informed the conspirators that they must re-work "the culture created by the whole development of mankind..." He told these young communists that "only by re-working this culture, is it possible to build proletarian (communist) culture..." Music, of course, is misused as a part of this communist "cultural" war against mankind. In a book published by the communist publishing house, International Publishers, during 1952, and entitled How Music Expresses Ideas, the author Sidney Finkelstein used the above quote by Lenin in relation to music.[8]

Personal life and death[]

While friends did not know whether Finkelstein had a family of his own, two of his closest friends were Phillip Bonosky and Herbert Aptheker.[9]

In his 1922 novel Babbitt, Sinclair Lewis included a character named "Sidney Finkelstein" (a ladies' ready-to-wear buyer for Parcher & Stein's department store) — no relation.

Sidney Finkelstein died age 64 on January 14, 1974, in Brooklyn, New York.[1][3]

Finkelstein had two brothers who survived him.[3]

Works[]

Finkelstein wrote nearly a dozen books and scores of articles.[3]

- Books

- Art and Society (1947)[10]

- Jazz, A People's Music (1948)[11]

- Jazz (1951)[14]

- How Music Expresses Ideas (1952)[15]

- Realism in Art (1954)[19]

- Charles White: Ein Künstler Amerikas (1955)[20]

- Composer and Nation: The Folk Heritage of Music (1960)[21]

- Existentialism and Alienation in American Literature (1965)[22]

- Sense and Nonsense of McLuhan (1968)[23]

- The Young Picasso (1969)

- Who Needs Shakespeare? (1973)[24]

- Contributions

- James Fenimore Cooper: Short Stories from His Novels (1970)[25]

- Articles

- "The Folk Song is Back to Stay," Worker Magazine (6 March 1949)

- "Answering Attack on Marxism – New York City," Daily Worker (14 October 1949)[6]

- "Charles White's Humanist Art," Masses & Mainstream (1953)[26]

- "How Art Began," Masses & Mainstream (1954)[27]

- "Notes on Contemporary Music," Political Affairs (1957)[28]

Legacy[]

Finkelstein remains an ongoing expert source on jazz. In 2015, the New York Times cited him in an article on William Dieterle.[29] In 2018, Culture Matters wrote an appreciation of him, which summarized by saying, "Analyses of jazz and society will therefore run aground if they fail to consult Jazz: A People’s Music."[9] Finkelstein's analysis of Charles White (artist) has continued to receive citations up to 2020.[30]

The University of Massachusetts Amherst houses Finkelstein's papers, which include correspondence with publisher Angus Cameron, artist Rockwell Kent, writer John Howard Lawson, educator Howard Selsam, and music composer Virgil Thomson.[1]

See also[]

- Vanguard Records

- International Publishers

- Charles Seeger

- Eric Hobsbawn

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Finkelstein, Sidney Walter, 1909-1974". University of Massachusetts Amherst. 1947. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richard A. Reuss; JoAnne C. Reuss; Ralph Lee Smith; Ronald C. Cohen, eds. (2000). American Folk Music and Left-wing Politics, 1927-1957. Scarecrow Press. pp. 51 (consequence), 242 (turned), 269 (turned). Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Sidney Finkelstein, Music Critic, Dead". New York Times. 15 January 1974. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Godel, Greg (22 August 2017). "Coltrane's revolutionary musical journey". Culture Matters. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Peter Brooker; Andrew Thacker, eds. (2009). The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume II: North America 1894-1960. Oxford University Press. p. 854. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Investigation of Communism in the Metropolitan Music School, Inc., and Related Fields. USGPO. April 1957. pp. vii (synopsis), 624 (Popper), 672–680 (testimony). Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^

"Counterattack". American Business Consultants. 1957: 57 (12 April 1947), 116 (19 July 1957), 2 (unclear date 1957). Retrieved 30 July 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^

"The Weekly Crusader, Volume 5". Christian Crusade. 1964: 3–4. Retrieved 30 July 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Rosenberg, Daniel (12 January 2018). "Sidney Finkelstein: an appreciation of the great Marxist cultural critic". Culture Matters. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1947). Art and Society. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1948). "illustrations by Jules Halfant". Jazz: A People's Music. Citadel Press. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1975). Jazz: A People's Music. Da Capo Press. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (2018). "illustrations by Jules Halfant, new foreword by Geoffrey Jacques". Jazz: A People's Music. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1951). Jazz. G. Hatje. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1952). How Music Expresses Ideas. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1952). How Music Expresses Ideas. Current Book Distributors. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1952). How Music Expresses Ideas. Lawrence & Wishart. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1970). How Music Expresses Ideas. Lawrence & Wishart. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1954). Realism in Art. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1955). Charles White: Ein Künstler Amerikas. Verlag d. Kunst. p. 67. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1960). "foreword and afterword by Carmelo Peter Comberiati". Composer and Nation: The Folk Heritage of Music. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1965). Existentialism and Alienation in American Literature. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1968). Sense and Nonsense of McLuhan. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, Sidney (1973). Who Needs Shakespeare?. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Cooper, James Fenimore (1970). "excerpts and introduction by Sidney Finkelstein". James Fenimore Cooper: Short Stories from His Novels. International Publishers. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^

Finkelstein, Sidney (1953). "Charles White's Humanist Art". Masses & Mainstream. Retrieved 1 August 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^

Finkelstein, Sidney (June 1954). "How Art Began". Masses & Mainstream: 15–26. Retrieved 2 August 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^

Finkelstein, Sidney (March 1957). "Notes on Contemporary Music" (PDF). Political Affairs. Retrieved 1 August 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Hoberman, J (27 February 2015). "William Dieterle's 'Syncopation' on DVD: Bending Notes and Jazz History". New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Harris, Serafina (4 July 2020). "Charles White and the Purpose of Education". Organization for Positive Peace. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

External links[]

- University of Massachusetts Amherst - Sidney Finkelstein Papers

- Library of Congress catalog

- Communism and Jazz (Side B)

- Photo

- Eddie Chambers: Sidney Finkelstein on Charles White

- American music critics

- 20th-century American historians

- 1909 births

- 1974 deaths

- Writers from New York City

- Historians from New York (state)