Sinking of U-864

| Action of 9 February 1945 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Second World War, Battle of the Atlantic | |||||||

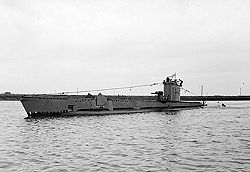

HMS Venturer in August 1943 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| HMS Venturer | U-864 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

U-864 with all 73 hands | ||||||

During the action of 9 February 1945, HMS Venturer, a V-class submarine of the Royal Navy, which was patrolling the waters around Fedje Island, off the Norwegian coast in the North Sea, attacked and sank the German U-boat German submarine U-864.

The sinking is the only incident where one submarine sank another in combat while both were at periscope depth.

Background[]

U-864[]

U-864 was a Type IX U-boat on a clandestine mission, Operation Caesar, to the Empire of Japan.[1] On 6 February 1945, U-864 passed through the Fedje area off the Norwegian coast without being detected. In 1986, G. P. Jones wrote that sound probably came from "noisy machinery".[2] In 2013, Preisler and Sewell wrote that an air compressor may have been wrongly installed or had worn out causing the engine to misfire with "loud, fitful vibrations".[3] There were many Allied (primarily British) ships, submarines and aircraft in the area on anti-submarine patrol. U-864's commander, Ralf-Reimar Wolfram, decided to return to the pens at Bergen to repair the engine. By this stage of the war the German machine cypher, Enigma, had been broken by the British and the Royal Navy were concerned the secret cargo might enable the Japanese to extend the duration of the Pacific War.[citation needed] They dispatched Venturer to intercept and destroy U-864.

HMS Venturer[]

Venturer (Lieutenant Jimmy Launders) received a brief message from the Admiralty,

Important Secret U-boats probably use following routes: from 60° 40' North, 004° 26' East, Course 110° r/v off Hellisoy 1. Probable that U-boats proceed to seaward off r/v

— [4]

Launders boldly decided to switch off Venturer's ASDIC (active sonar) and rely solely on hydrophones, to try to detect U-864 without being detected.[5] U-864 sailed back past Fedje and the area where Venturer was located.

Action[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

As Venturer continued her patrol of the waters around Fedje, her hydrophone operator noticed a strange sound which he could not identify. He thought that the noise sounded as though some local fisherman had started a diesel engine.[5] Launders decided to track the strange noise. Then the officer of the watch on Venturer's periscope noticed what they thought was another periscope above the surface of the water.[5] It is highly likely he had, in fact, spotted the U-boat's snorkel. The snorkel was still a new device and probably unknown to Launders and his crew.

The snorkel limited the U-boat's speed and depth. For Launders' hydrophone operator to hear diesel noises from a submerged U-boat, the snorkel would have had to be in operation. The noise of the diesel engines made the U-boat's hydrophones much less effective and it is doubtful U-864 would have heard Venturer running slowly on her electric motors.

Combined with the hydrophone reports of the strange noise, which he determined to be coming from a submerged vessel, Launders surmised they had found U-864.[5] He tracked the U-boat by hydrophone, hoping she would surface and allow a clear shot. U-864 remained at snorkel depth and as the hydrophone plot emerged, she was seen to be zigzagging. This made the German submarine quite safe according to the assumptions of the time.

Launders tracked the U-boat for several hours and it became obvious she was not going to surface, but he needed to attack her anyway – his batteries had only a limited life. It was theoretically possible to compute a firing solution in all four dimensions – time, distance, bearing and target depth – but this had never been attempted in practice because it was assumed that performing the complex calculations would be impossible, plus there were unknown factors that had to be approximated.

In most torpedo attacks, the target would have been seen; the target's angle relative to the attacker and its bearing would be observed, then a rangefinder in the periscope used to establish the distance to the target; from this speed could be derived and a basic mechanical computer would offset the aiming point for the torpedo, the depth of which had to be set based on target identification. Too deep and the torpedo would pass under the target, too shallow (in this instance) it would miss above. Launders could only estimate the depth of his target. As they tried to manoeuvre into a firing position without giving their position away by creating excessive noise, or exhausting their own batteries.

Launders made the calculations and assumptions about U-864's defensive manoeuvres, then ordered the firing of all four of his bow torpedo tubes. The torpedoes were fired with a 17.5 second delay between each pair, and at different depths. U-864 attempted to evade once it heard the torpedoes coming, but was not agile when diving or turning; additionally, time would have been needed to retract the snorkel, disengage the diesel and start the electric motors.[citation needed] The fourth torpedo hit. U-864 sank with all hands.

Aftermath[]

U-864 sank 31 nmi (36 mi; 57 km) from the relative safety of the U-boat pens in Bergen. Launders was awarded a bar to his DSO and several members of his crew were also decorated.[6] The action was the first and so far only battle ever to have been fought entirely under water.[7]

References[]

- ^ Preisler & Sewell 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Jones 1986, p. 197.

- ^ Preisler & Sewell 2013, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Preisler & Sewell 2013, p. 164.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d U864: Hitler's Deadly Last Secret, Discovery Communications, 2006

- ^ Preisler & Sewell 2013, p. 183.

- ^ Preisler & Sewell 2013, p. 7.

Bibliography[]

- Akermann, Paul (2002). Encyclopaedia of British Submarines 1901–1955. Penzance: Periscope Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904381-05-1.

- Jones, G. P. (1986). "Chapter XVII: Venturer". Submarines versus U-Boats. London: William Kimber. pp. 187–197. ISBN 978-0-7183-0626-7.

- Preisler, J.; Sewell, K. (2013) [2012]. Code-Name Caesar: The Secret Hunt for U-boat 864 during World War II (repr. Souvenir Press, London ed.). New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-285-64203-4.

Further reading[]

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (2005) [1972]. Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (3rd rev. ed.). London: Chatham. ISBN 1-86176-257-7.

- Roskill, S. W. (2004) [1961]. Butler, J. (ed.). The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Offensive Part II 1st June 1944 – 14th August 1945. History of the Second World War Military Series (pbk. repr. Imperial War Museum Department of Printed Books and Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84342-806-0.

External links[]

- "U-864: Hitler's Deadly Last Secret". History Television. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "HMS Venturer". German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "U-864". German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net.

- Battle of the Atlantic

- Naval battles of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Naval battles of World War II involving Germany

- Submarine warfare in World War II

- Conflicts in 1945

- 1945 in Norway

- February 1945 events