Snailfish

| Snailfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Snailfish (probably ) caught in the eastern Bering Sea | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scorpaeniformes |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | Liparidae T. N. Gill, 1861 |

| Type genus | |

| Liparis Scopoli, 1777

| |

The Liparidae, commonly known as snailfish or sea snails,[1] are a family of marine scorpaeniform fishes.

Widely distributed from the Arctic to Antarctic Oceans, including the oceans in between, the snailfish family contains more than 30 genera and about 410 described species,[2] but there are also many undescribed species.[3] Snailfish species can be found in depths ranging from shallow surface waters to greater than 8,000 meters, and species of the Liparid family have been found in seven ocean trenches.[4] They are closely related to the sculpins (family Cottidae) and lumpfish (family Cyclopteridae). In the past, snailfish were sometimes included within the latter family.

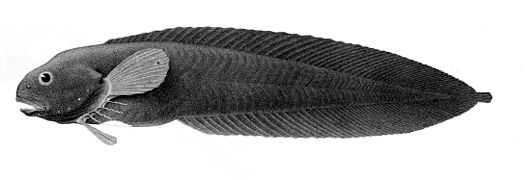

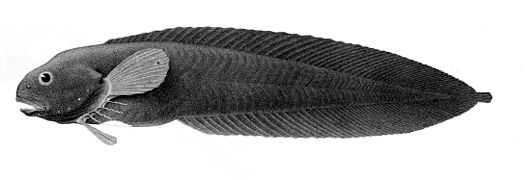

Description[]

The snailfish family is poorly studied and few specifics are known. Their elongated, tadpole-like bodies are similar in profile to the rattails. Their heads are large (compared to their size) with small eyes; their bodies are slender to deep, tapering to very small tails. The extensive dorsal and anal fins may merge or nearly merge with the tail fin. Snailfish are scaleless with a thin, loose gelatinous skin; some species, such as Acantholiparis opercularis have prickly spines, as well. Their teeth are small and simple with blunt cusps. The deep-sea species have prominent, well-developed sensory pores on the head, part of the animals' lateral line system.[5]

The pectoral fins are large and provide the snailfish with its primary means of locomotion although they are fragile. They are benthic fish with pelvic fins modified to form an adhesive disc; this nearly circular disc is absent in Paraliparis and Nectoliparis species. Snailfish range in size from Paraliparis australis at 5 cm (2.0 in) to Polypera simushirae at some 77 cm (30 in) in length. The latter species may reach a weight of 11 kg (24 lb), but most species are smaller.[6] Snailfish are of no interest to commercial fisheries.

It was difficult to initially study snailfish because they would implode upon being brought to the surface, but researchers did manage to study the bones of the animal.

Occurrence and habitat[]

The habitats occupied by snailfish are as widely variable in terms of size. They are found in oceans worldwide, ranging from shallow intertidal zones to depths of slightly more than 8,000 m (26,000 ft). This is a wider depth range than any other family of fish.[7] They are strictly found in cold waters, meaning that species of tropical and subtropical regions strictly are deepwater.[3][7][8] They are common in most cold marine waters and are highly resilient, with some species, such as Liparis atlanticus and Liparus gibbus, having type-1 antifreeze proteins.[9] It is the most species-rich family of fish in the Antarctic region, generally found in relatively deep waters (shallower Antarctic waters are dominated by Antarctic icefish).[10]

The diminutive (Liparis inquilinus) of the northwestern Atlantic is known to live out its life inside the mantle cavity of the scallop Placopecten magellanicus. Liparis tunicatus lives amongst the kelp forests of the Bering Strait and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The single species in genus Rhodichthys is endemic to the Norwegian Sea.[11] Other species are found on muddy or silty bottoms of continental slopes.

In October 2008, a UK-Japan team discovered a shoal of Pseudoliparis amblystomopsis snailfish at a depth of approximately 7,700 m (25,300 ft) in the Japan Trench.[12] These were, at the time, the deepest living fish ever recorded on film. The record was surpassed by a snailfish that was filmed at a depth of 8,145 m (26,722 ft) in December 2014 in the Mariana Trench,[13] and extended in May 2017 when another was filmed at a depth of 8,178 m (26,831 ft) in the Mariana Trench.[7][14] The species in these deepest records remain undescribed, but it has been referred to as the "ethereal snailfish". The deepest-living described species is Pseudoliparis swirei, also of the Mariana Trench, which has been recorded to 8,076 m (26,496 ft).[7][15] In general, snailfish (notably genera Notoliparis and Pseudoliparis) are the most common and dominant fish family in the hadal zone.[15] Through genomic analysis it was found that Pseudoliparis swirei possesses multiple molecular adaptions to survive the intense pressures of a deep sea environment, including pressure-tolerant cartilage, pressure-stable proteins, increased transport protein activity, higher cell membrane fluidity, and loss of eyesight and other visual characteristics such as color.[4] There are indications that the larvae of at least some hadal snailfish species spend time in open water at relatively shallow depths, less than 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[16]

Reproduction and life span[]

Reproductive strategies vary extensively among snailfish species. As far as known, all species lay eggs that are relatively large in size (diameter up to 9.4 mm or 0.37 in).[7] The number of eggs varies extensively depending on species.[17] Some deposit their egg mass among cold-water corals, kelp, stones, or xenophyophores.[3][18][19] It is possible that the male guards the egg mass.[18] At least one species, Careproctus ovigerus of the North Pacific, is known to practice mouth brooding; that is, the male snailfish carries the developing eggs around in his mouth. Some other species of the genus Careproctus are parasitic, laying their eggs in the gill cavities of king crabs.[3] One species, Careproctus rhodomelas, was found instead to be a batch spawner, laying multiple batches of large eggs multiple times throughout its lifetime.[20] After the eggs hatch, some species rapidly reach the adult size and only live for about one year,[18] but others have life spans of more than a decade.[21]

Diet[]

Upon a 2007 study of fish in the hadal zone, it was revealed that snailfish usually feed on amphipods, which were also attracted to the chum that the researchers left out, Larval snailfish feed on a mix of plankton, small and large copepods, and amphipods. The diet of larval snailfish contains 28 food categories, mainly copepods and amphipods. [22]

Snailfish prey can be grouped in six main categories: gammarid, krill, natantian decapods, other crustaceans, fish, and others.[23] Size also affects snailfish diets. Species smaller than 50 mm primarily eat gammarids, while species larger than 100 mm primarily eat natantian decapods. Species larger than 150 mm have the highest proportion of fish in their diet. Larger snailfish species tend to be piscivorous. [23]

Genera[]

This family currently contains these genera as of 2020:[2]

- Acantholiparis Gilbert & Burke, 1912

- Aetheliparis Stein, 2012[24]

- Allocareproctus Pitruk & Fedorov, 1993

- Careproctus Krøyer, 1862

- Crystallichthys Jordan & Gilbert, 1898

- Eknomoliparis Stein, Meléndez C. & Kong U., 1991

- Elassodiscus Gilbert & Burke, 1912

- Eutelichthys Tortonese, 1959

- Genioliparis Andriashev & Neyelov, 1976

- Gyrinichthys Gilbert, 1896

- Liparis Scopoli, 1777

- Lipariscus Gilbert, 1915

- Lopholiparis Orr, 2004

- Menziesichthys Nalbant & Mayer, 1971

- Nectoliparis Gilbert & Burke, 1912

- Notoliparis Andriashev, 1975

- Osteodiscus Stein, 1978

- Palmoliparis Balushkin, 1996

- Paraliparis Collett, 1879

- Polypera Burke, 1912

- Praematoliparis Andriashev, 2003

- Prognatholiparis Orr & Busby, 2001

- Psednos Barnard, 1927

- Pseudoliparis Andriashev, 1955

- Pseudonotoliparis Pitruk, 1991

- Rhinoliparis Gilbert, 1896

- Rhodichthys Collett, 1879

- Squaloliparis Pitruk & Fedorov, 1993

- Temnocora Burke, 1930

- Volodichthys Balushkin, 2012[25]

Careproctus ovigerus (juvenile)

Paraliparis bathybius

Rhodichthys regina

References[]

- ^ "The Sea Snails. Family Liparidae". Gulf of Maine Research Institute. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2015). "Liparidae" in FishBase. February 2015 version.

- ^ a b c d Gardner, J.R.; J.W. Orr; D.E. Stevenson; I. Spies; D.A. Somerton (2016). "Reproductive Parasitism between Distant Phyla: Molecular Identification of Snailfish (Liparidae) Egg Masses in the Gill Cavities of King Crabs (Lithodidae)". Copeia. 104 (3): 645–657. doi:10.1643/CI-15-374.

- ^ a b Wang, Kun; Shen, Yanjun; Yang, Yongzhi; Gan, Xiaoni; Liu, Guichun; Hu, Kuang; Li, Yongxin; Gao, Zhaoming; Zhu, Li; Yan, Guoyong; He, Lisheng (2019). "Morphology and genome of a snailfish from the Mariana Trench provide insights into deep-sea adaptation". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (5): 823–833. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0864-8. ISSN 2397-334X.

- ^ Chernova, Natalia (2006). "New and rare snailfishes (Liparidae, Scorpaeniformes) with the description of four new species from the Southern Hemisphere and tropical east Pacific". Journal of Ichthyology. 46: S1–S14. doi:10.1134/S0032945206100018. hdl:1834/17070.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Polypera simushirae" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- ^ a b c d e Gerringer, M.E.; T.D. Linley; P.H. Yancey; A.J. Jamieson; E. Goetze; J.C. Drazen (2016). "Pseudoliparis swirei sp. nov.: A newly-discovered hadal snailfish (Scorpaeniformes: Liparidae) from the Mariana Trench". Zootaxa. 4358 (1): 161–177. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4358.1.7. PMID 29245485.

- ^ Sakurai, H.; G. Shinohara (2008). "Careproctus rotundifrons, a New Snailfish (Scorpaeniformes: Liparidae) from Japan". Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci. Ser. A (Suppl. 2): 39–45.

- ^ Evans, R.E.; G.L. Fletcher (2001). "Isolation and characterization of type I antifreeze proteins from Atlantic snailfish (Liparis atlanticus) and dusky snailfish (Liparis gibbus)". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 1547 (Suppl. 2): 235–244. doi:10.1016/S0167-4838(01)00190-X. PMID 11410279.

- ^ Eastman, J.T.; M.J. Lannoo (1998). "Morphology of the Brain and Sense Organs in the Snailfish Paraliparis devriesi: Neural Convergence and Sensory Compensation on the Antarctic Shelf". Journal of Morphology. 237 (3): 213–236. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-4687(199809)237:3<213::aid-jmor2>3.0.co;2-#. PMID 9734067.

- ^ Hogan, C.M. (2011): Norwegian Sea. Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Saundry, P. & Cleveland, C.J. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- ^ Morelle, R. (2008). "'Deepest ever' living fish filmed". BBC News.

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (2014-12-19). "New record for deepest fish". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ^ "Ghostly fish in Mariana Trench in the Pacific is deepest ever recorded". CBC News. 2017-08-25. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ^ a b Linley, T.D.; M.E. Gerringer; P.H. Yancey; J.C. Drazen; C.L. Weinstock; A.J. Jamieson (2016). "Fishes of the hadal zone including new species, in situ observations and depth records of Liparidae". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 114: 99–110. Bibcode:2016DSRI..114...99L. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2016.05.003.

- ^ Gerringer, M.E.; A.H. Andrews; G.R. Huus; K. Nagashima; B.N. Popp; T.D. Linley; N.D. Gallo; M.R. Clark; A.J. Jamieson; J.C. Drazen (2017). "Life history of abyssal and hadal fishes from otolith growth zones and oxygen isotopic compositions". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 132: 37–50. Bibcode:2018DSRI..132...37G. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2017.12.002.

- ^ Stein, D.L. (1980). "Aspects of Reproduction of Liparid Fishes from the Continental Slope and Abyssal Plain off Oregon, with Notes on Growth". Copeia. 1980 (4): 687–699. doi:10.2307/1444445. JSTOR 1444445.

- ^ a b c Kawasaki, I.; J. Hashimoto; H. Honda; A. Otake (1983). "Selection of Life Histories and its Adaptive Significance in a Snailfish Liparis tanakai from Sendai Bay". Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries. 49 (3): 367–377. doi:10.2331/suisan.49.367.

- ^ Levin, Lisa A.; Rouse, Greg W. (April 2020). "Giant protists (xenophyophores) function as fish nurseries". Ecology. 101 (4). doi:10.1002/ecy.2933. ISSN 0012-9658. PMC 7341444. PMID 31742677.

- ^ Takemura, A.; Tamotsu, S.; Miwa, T.; Yamamoto, H. (2010-10-14). "Preliminary results on the reproduction of a deep-sea snailfish Careproctus rhodomelas around the active hydrothermal vent on the Hatoma Knoll, Okinawa, Japan". Journal of Fish Biology. 77 (7): 1709–1715. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02789.x. ISSN 0022-1112.

- ^ Orlov, A.M.; A.M. Tokranov (2011). "Some Rare and Insufficiently Studied Snailfish (Liparidae, Scorpaeniformes, Pisces) in the Pacific Waters off the Northern Kuril Islands and Southeastern Kamchatka, Russia". ISRN Zoology. 201: 341640. doi:10.5402/2011/341640.

- ^ "Spatial distribution and diet of larval snailfishes (Liparis fabricii, Liparis gibbus, Liparis tunicatus) in the Canadian Beaufort Sea". Oceanologia. 58 (2): 117–123. 2016-04-01. doi:10.1016/j.oceano.2015.12.001. ISSN 0078-3234.

- ^ a b Tomiyama, Takeshi; Yamada, Manabu; Yoshida, Tetsuya. "Seasonal migration of the snailfish Liparis tanakae and their habitat overlap with 0-year-old Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 93 (7): 1981–1987. doi:10.1017/S0025315413000544. ISSN 0025-3154.

- ^ Stein D.L. (2012). "A Review of the Snailfishes (Liparidae, Scorpaeniformes) of New Zealand, Including Descriptions of a New Genus and Sixteen New Species". Zootaxa. 3588: 1–54. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3588.1.1.

- ^ Balushkin A.V. (2012). "Volodichthys gen. nov. New Species of the Primitive Snailfish (Liparidae: Scorpaeniformes) of the Southern Hemisphere. Description of New Species V. solovjevae sp. nov. (Cooperation Sea, the Antarctic)". Journal of Ichthyology. 52 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1134/s0032945212010018.

External links[]

Media related to Liparidae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Liparidae at Wikimedia Commons

- Liparidae