Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate

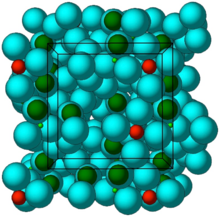

Crystal structure of ZS-9. Blue spheres = oxygen atoms, red spheres = zirconium atoms, green spheres = silicon atoms. | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lokelma |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a618035 |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Not absorbed |

| Excretion | Feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | (2Na·H2O·3H4SiO4·H4ZrO6)n |

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9), sold under the brand name Lokelma, is a medication used to treat high blood potassium.[1] Onset of effects occurs in one to six hours.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include swelling and low blood potassium.[1] Use is likely safe in pregnancy and breastfeeding.[1] It works by binding potassium ions in the gastrointestinal tract which is then lost in the stool.[1][2]

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate was approved for medical use in the European Union and in the United States in 2018.[1][3][4] It was developed by AstraZeneca.[1]

Medical use[]

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate is used to treat high blood potassium.[1] Onset of effects occurs in one to six hours.[1]

One review found a decrease in potassium of 0.17 mEq/L at one hour and 0.67 mEq/L at 48 hours.[5]

It appears effective in people with chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and heart failure.[2] Use has been studied for up to a year.[2]

Mechanism of action[]

ZS-9 is a zirconium silicate. Zirconium silicates have been extensively used in medical and dental applications because of their proven safety.[6] 11 zirconium silicates were screened by an iterative optimization process. ZS-9 selectively captures potassium ions, presumably by mimicking the actions of physiologic potassium channels.[7] ZS-9 is an inorganic cation exchanger crystalline with a high capacity to entrap monovalent cations, specifically potassium and ammonium ions, in the GI tract. ZS-9 is not systemically absorbed; accordingly, the risk of systemic toxicity may be minimized.[citation needed]

Background[]

Hyperkalemia is rare among those who are otherwise healthy.[8] Among those who are in hospital, rates are between 1% and 2.5%.[9] Common causes include kidney failure, hypoaldosteronism, and rhabdomyolysis.[10] A number of medications can also cause high blood potassium including spironolactone, NSAIDs, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors.[10]

There is no universally accepted definition of what level of hyperkalemia is mild, moderate, or severe.[11] However, if hyperkalemia causes any ECG change it is considered a medical emergency[11] due to a risk of potentially fatal abnormal heart rhythms and is treated urgently.[11] Potassium levels greater than 6.5 to 7.0 mmol/L in the absence of ECG changes are managed aggressively.[11] Several approaches are used to treat hyperkalemia.[11] Other approved potassium binders in the United States include patiromer and sodium polystyrene sulfonate.[12]

Hyperkalemia, particularly if severe, is a marker for an increased risk of death.[13] However, there is disagreement regarding whether a modestly elevated levels directly causes problems. One viewpoint is that mild to moderate hyperkalemia is a secondary effect that denotes underlying medical problems.[13] Accordingly, these problems are both proximate and ultimate causes of death,[13]

History[]

Regulatory[]

In the United States, regulatory approval of ZS-9 was rejected by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in May 2016, due to issues associated with manufacturing.[14] On May 18, 2018, the FDA approved sodium zirconium cyclosilicate for treatment of adults with hyperkalemia.[15]

It was first practically synthesized by UOP in the late 1990s. (reference -zirconium silicate and zirconium germate molecular sieves and the process of using the same, US Patent 5,891,472) the recognition of the unique ion exchange properties and the potential use to remove toxins from the body were identified shortly thereafter ("process for removing toxins from bodily fluids using zirconium or titanium microporous compositions, US patent 6,332,985).

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Hoy SM (October 2018). "Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate: A Review in Hyperkalaemia". Drugs. 78 (15): 1605–1613. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-0991-6. PMC 6433811. PMID 30306338.

- ^ "Lokelma EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Lokelma (sodium zirconium cyclosilicate)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 8 June 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Meaney CJ, Beccari MV, Yang Y, Zhao J (April 2017). "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Patiromer and Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate: A New Armamentarium for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia". Pharmacotherapy. 37 (4): 401–411. doi:10.1002/phar.1906. PMC 5388568. PMID 28122118.

- ^ Denry I, Kelly JR. State of the art of zirconia for dental applications. Dental Materials. Volume 24, Issue 3, March 2008, Pages 299–307

- ^ Stavros F, Yang A, Leon A, Nuttall M, Rasmussen HS (2014). "Characterization of structure and function of ZS-9, a K+ selective ion trap". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e114686. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k4686S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114686. PMC 4273971. PMID 25531770.

- ^ Kovesdy CP (March 2017). "Updates in hyperkalemia: Outcomes and therapeutic strategies". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 18 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1007/s11154-016-9384-x. PMC 5339065. PMID 27600582.

- ^ McDonald TJ, Oram RA, Vaidya B (October 2015). "Investigating hyperkalaemia in adults". BMJ. 351: h4762. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4762. PMID 26487322. S2CID 206907572.

- ^ a b Lehnhardt A, Kemper MJ (March 2011). "Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of hyperkalemia". Pediatric Nephrology. 26 (3): 377–84. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1699-3. PMC 3061004. PMID 21181208.

- ^ a b c d e Taal, M.W.; Chertow, G.M.; Marsden, P.A.; Skorecki, K.; Yu, A.S.L.; Brenner, B.M. (2012). Brenner and Rector's The Kidney (Chapter 17, page 672, 9th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-6193-9.

- ^ Watson M, Abbott KC, Yuan CM (October 2010). "Damned if you do, damned if you don't: potassium binding resins in hyperkalemia". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 5 (10): 1723–6. doi:10.2215/CJN.03700410. PMID 20798253.

- ^ a b c Elliott MJ, Ronksley PE, Clase CM, Ahmed SB, Hemmelgarn BR (October 2010). "Management of patients with acute hyperkalemia". CMAJ. 182 (15): 1631–5. doi:10.1503/cmaj.100461. PMC 2952010. PMID 20855477.

- ^ Ben Adams (May 27, 2016). "AstraZeneca's $2.7B hyperkalemia drug ZS-9 rejected by FDA". FierceBiotech.

- ^ "Lokelma (Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate) FDA Approval History".

Further reading[]

External links[]

- "Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Drugs not assigned an ATC code

- Chelating agents used as drugs

- Nephrology procedures

- Zirconium compounds

- AstraZeneca brands

- Potassium