Sophia Dorothea of Celle

| Sophia Dorothea of Celle | |

|---|---|

| Electoral Princess of Hanover | |

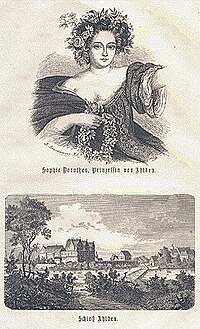

Portrait from the 1680s displayed at Herrenhausen Palace museum | |

| Born | 15 September 1666 Celle, Germany |

| Died | 13 November 1726 (aged 60) Ahlden, Germany |

| Burial | Stadtkirche, Celle, Germany |

| Spouse | |

| Issue |

|

| House | Hanover |

| Father | George William, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

| Mother | Éléonore Desmier d'Olbreuse |

Sophia Dorothea of Brunswick-Lüneburg-Celle (15 September 1666 – 13 November 1726) was the repudiated wife of future King George I of Great Britain, and mother of George II. The union with her first cousin was a marriage of state, arranged by her father George William, her father-in-law the Elector of Hanover, and her mother-in-law, Electress Sophia of Hanover, first cousin of King Charles II of England. She is best remembered for her alleged affair with Count Philip Christoph von Königsmarck that led to her being imprisoned in the Castle of Ahlden for the last thirty years of her life.

Life[]

Early years[]

Born in Celle on 15 September 1666, Sophia Dorothea was the only surviving daughter of George William, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg by his morganatic wife, Eléonore Desmier d'Olbreuse (1639–1722), Lady of Harburg, a Huguenot French noblewoman.

She grew up carefree in a loving environment. Her parents were, unlike many noble and royal couples of that time, deeply in love with each other and gave warmth and affection to their bright and talented daughter. As Sophia Dorothea was the product of a morganatic union and without any rights as a member of the House of Brunswick, her father wanted to secure her future. He transferred large assets to her over time, which made her an interesting marriage candidate. Candidates for her hand included Augustus Frederick, Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Frederick Charles, Duke of Württemberg-Winnental, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria and even King Charles XI of Sweden.

Sophia Dorothea's status was enhanced when, by Imperial order dated 22 July 1674 and in recognition to the military assistance given by her father to Emperor Leopold I, she and her mother received the higher title of "Countess of Harburg and Wilhelmsburg" (Gräfin von Harburg und Wilhelmsburg) with the allodial rights over those demesnes.[1]

At first, her parents agreed to the marriage between Sophia Dorothea and Augustus Frederick, Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, the eldest son of their distant relative Anthony Ulrich, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, who had supported the love affair between George William and Éléonore from its beginnings. The official betrothal was signed on 20 December 1675. Unfortunately the groom was mortally wounded at the siege of Philippsburg on 9 August 1676.

Elevation of birth status and marriage[]

After the death of his daughter's fiancé, George William was keen to negotiate an agreement over the inheritance of the Duchy of Lüneburg. He initially approached his younger brother Ernest Augustus, Elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg, to arrange a marriage between Sophia Dorothea and Ernest Augustus's eldest son George Louis, the future George I of Great-Britain. However, both his brother and sister-in-law, Sophia of the Palatinate, had misgivings about the proposed match due to the circumstances of Sophia Dorothea's birth.

After the rejection of his daughter, George William decided to improve once for all the status of Sophia Dorothea and her mother; by contract signed on 22 August 1675, and in open violation of his previous promise never to marry, George William declared that Éléonore was his lawful wife in both church and state, with a second wedding ceremony being held at Celle on 2 April 1676. Ernest Augustus and Sophia stayed away from this second wedding.[2] Twenty-two days later, on 24 April, Eléonore was officially addressed at court as Duchess of Brunswick and Sophia Dorothea became legitimate.[2]

This development alarmed George William's relatives. Now legitimated by the official marriage of her parents, Sophia Dorothea could threaten the planned union of the Lüneburg territories. Finally, by an official agreement signed on 13 July 1680, the Lüneburg royal family recognised Éléonore as Duchess of Brunswick and, most importantly, Sophia Dorothea was declared Princess of Brunswick-Lüneburg-Celle, with all appertaining rights of birth. George Louis' parents finally agreed to the proposed union of their son to Sophia Dorothea. In the teeth of opposition from both Sophia Dorothea and his wife Eléonore, George William went ahead with arrangements for the wedding.[3]

The wedding took place on 21 November 1682. From its early days, the marriage was a complete failure. George Louis and his mother, Sophia of the Palatinate, had accepted the union, but felt contempt towards Sophia Dorothea, believing that her birth and manners were inferior.

Explaining her reluctant support for the marriage, Duchess Sophia wrote to her niece Elizabeth Charlotte, Duchess of Orléans:

"One hundred thousand thalers a year is a goodly sum to pocket, without speaking of a pretty wife, who will find a match in my son George Louis, the most pigheaded, stubborn boy who ever lived, who has round his brains such a thick crust that I defy any man or woman ever to discover what is in them. He does not care much for the match itself, but one hundred thousand thalers a year have tempted him as they would have tempted anybody else".[4]

George Louis treated his bride with coldness and formality. He frequently scolded her for her lack of etiquette, and the two had loud and bitter arguments. Nevertheless, they managed to conceive two children: George Augustus (future King George II of Great Britain; born on 30 October 1683) and Sophia Dorothea (future Queen consort in Prussia and Electress consort of Brandenburg; born on 16 March 1687). Having done his duty by the succession, George Louis acquired a mistress, Melusine von der Schulenburg, and started increasingly to neglect his wife. His parents asked him to be more circumspect with his mistress, fearful that a disruption in the marriage would threaten the payment of the 100,000 thalers he was to receive as part of Sophia Dorothea's dowry and inheritance from her father.

Affair with Königsmarck[]

Around 1690, Sophia Dorothea was reunited with the Swedish Count Philip Christoph von Königsmarck, whom she had known in her childhood when he was a page at the court of Celle. At first, their meetings were brief and sporadic, but this probably changed in 1691 and initially their closeness went unnoticed. Eventually, the open preference that Sophia Dorothea showed Königsmarck aroused suspicions, and by 1694 rumours filled the Hanoverian court that the Electoral Princess and Count von Königsmarck were having a love affair. Contemporary sources show that Sophia Dorothea and Königsmarck were presumed to have had a sexual relationship since March 1692, something she denied her entire life.[5]

After a violent argument with her husband, Sophia Dorothea travelled to her parents in Celle in the spring of 1694 to persuade them to support an official separation from her husband. George William and Eléonore opposed it. Sophia Dorothea's father was waging war against Denmark and Sweden and was dependent on the help of his brother Ernest Augustus, so he sent his daughter back to the Hanover court.

In the summer of 1694 Sophia Dorothea, together with Königsmarck and her lady-in-waiting Eleonore von dem Knesebeck, planned an escape, hoping to find refuge either in Wolfenbüttel under the protection of Duke Anthony Ulrich, or in the Electorate of Saxony, where the Swedish Count held an officer position as major general of the cavalry.[6] But their plan was discovered and the disaster struck the lovers.

Königsmarck's disappearance[]

Countess Clara Elisabeth von Platen, a former mistress of Elector Ernest Augustus, had tried in January 1694 to persuade Königsmarck to marry her daughter Sophia Charlotte, but he had refused. Offended, she revealed to the Electoral Prince George Louis the love affair between his wife and the Swedish Count as well as their planned escape. Soon, the whole of Hanover knew of the planned elopement and the scandal erupted.

On the night of 11 July 1694 and after a meeting with Sophia Dorothea in the Leineschloss, Königsmarck disappeared without a trace. According to diplomatic sources from Hanover's enemies, he appears to have been killed on the orders, tacit or direct, of the Electoral Prince or of his father the Elector, and his body thrown into the river Leine weighted with stones. Those same sources claimed that four of Ernest Augustus's courtiers committed the murder, one of whom, Don Nicolò Montalbano, received the enormous sum of 150,000 thalers, about one hundred times the annual salary of the highest paid minister.[7] Sophia Dorothea would never find out what had happened to her lover. No trace of him was discovered.[7]

Königsmarck's disappearance turned into a diplomatic affair when not only relatives and the Hanoverian population but foreign diplomats and their governments began to puzzle over it. King Louis XIV of France questioned his sister-in-law Elizabeth Charlotte, the maternal first-cousin of the Electoral Prince, but she pretended ignorance. The French king then sent agents to Hanover, but they could no more shed light on the mystery than King Augustus II of Poland, who spent weeks searching for his missing general.

In retaliation, the Elector of Hanover Ernest Augustus and his brother George William, Sophia Dorothea's father, turned to Emperor Leopold I with a formal complaint against the King of Poland. If the Imperial court didn't prevent Augustus II from carrying out "unfriendly acts" against Hanover and Celle, they would withdraw their troops from the Grand Alliance in the war against France. Although the Emperor and the Elector Frederick III of Brandenburg exerted pressure on Augustus II, the Polish envoy continued the investigation and even faced Count von Platen, telling him that von Königsmarck had either been captured or killed on the orders of his wife the Countess, out of jealousy.[8]

In 2016, construction workers found human bones in a pit while installing an elevator in the Leineschloss.[9] These were initially assumed to be von Königsmarck's remains, but anthropological examinations of the bones showed that assumption to be unlikely.

The love letters between Sophia Dorothea and Königsmarck[]

When his affair with Sophia Dorothea threatened to become public, von Königsmarck handed their love letters to his brother-in-law, the Swedish Count Carl Gustav von Löwenhaupt. The latter's heirs later offered the correspondence to the House of Hanover for money but they demanded such a high price that the court rebuffed them and questioned the authenticity of the letters. The correspondence was published in the middle of the 19th century and the majority of the letters are now in the possession of Lund University in Sweden. A few of the letters ended up in the possession of Sophia Dorothea's grandson, King Frederick the Great of Prussia, after his sister, Swedish Queen consort Louisa Ulrika, allegedly stole them and sent them to him. Today the authenticity of the letters has been established beyond any doubt.[10]

The lovers rarely dated their letters but they numbered most of them. The Hanoverian historian Georg Schnath calculated on the basis of the existing correspondence that there must have been originally 660 letters: 340 letters written by von Königsmarck and 320 by Sophia Dorothea. The missing letters seem to have been confiscated and destroyed by the Hanoverian authorities after the affair became public. State Archives in Hanover provide scant information about the critical years. Even the correspondence between Electress Sophia and her niece Elizabeth Charlotte, which could have shed some light on some of the events, was censored afterwards.[6]

Divorce and imprisonment[]

Hanover had dealt with von Königsmarck, but that was not enough to restore the honour of the Electoral Prince George Louis in his own eyes. He demanded a legal separation from his wife, citing her as sole culprit on grounds of desertion. In addition to divorce proceedings, he had Sophia Dorothea imprisoned and transferred to Lauenau Castle in late 1694 and placed under house arrest. On 28 December 1694, the dissolution of the marriage was officially pronounced; the Electoral Princess was named as the guilty party for "maliciously leaving her husband". Under the judgment, Sophia Dorothea was forbidden to remarry or to see her children again;[11] official documents would remove her name, she was stripped of her title of Electoral Princess and churches in Hanover were no longer to mention her name in prayers. After the divorce, George Louis sent her to remote Ahlden House, a stately home on the Lüneburg Heath, which served as a prison appropriate to her status. Although the divorce judgment says nothing about continued imprisonment, she was never to regain her freedom.[6]

At the behest of her former husband and with the consent of her own father, Sophia Dorothea was imprisoned for life. George Louis confiscated the assets she brought to the marriage and allocated her an annual maintenance. She initially received 8,000 thalers for herself and her court, which was later raised to 28,000 thalers, a sum to which George Louis and her father George William paid in equal parts. She was detained in the north wing of the castle, a two-story half-timbered building, guarded 24 hours a day by 40 men-at-arms, 5 to 10 of whom were on duty at any one time. Her mail and visits were strictly controlled, though her mother had unlimited visiting rights. As far as historians know, she never attempted escape.

Initially, Sophia Dorothea was only allowed to walk unaccompanied inside the mansion courtyard; later, she was permitted under guard in the outdoor facilities. After two years in prison, she could take supervised trips two kilometres outside the castle walls.[11] Her stay in Ahlden was interrupted several times due to war or renovation work on the residence. During these times she was transferred to Celle Castle or to Essel. Her court included two ladies-in-waiting, several chambermaids and other household and kitchen staff. These had all been selected for their loyalty to Hanover.[11]

After her imprisonment, Sophia Dorothea was known as "Princess of Ahlden", after her new place of residence. At first, she was extremely apathetic and resigned to her fate; in later years she tried to obtain her release. When her former father-in-law died in 1698, she sent a humble letter of condolence to her former husband, assuring him that "she prayed for him every day and begged him on her knees to forgive her mistakes. She will be eternally grateful to him if he allows her to see her two children". She also wrote a letter of condolence to Electress Sophia, her ex-mother-in-law, claiming that she wanted nothing more than "to kiss your Highness' s hands before I die". Her requests were in vain: George Louis, later George I of Great Britain, would never forgive her, nor would his mother.

When Sophia Dorothea's father was on his deathbed in 1705, he wanted to see his daughter one last time to reconcile with her, but his Prime Minister, Count Bernstorff, objected and claimed that a meeting would lead to diplomatic problems with Hanover; George William no longer had the strength to assert himself and died without seeing his daughter.

Sophia Dorothea is remembered for a significant act of charity during her imprisonment: after the devastating local fire of Ahlden in 1715, she contributed considerable sums of money towards the town's reconstruction.

Death and burial[]

The death of her mother in 1722 left Sophia Dorothea alone and surrounded only by enemies, as Eléonore of Celle had been the only one to continue fighting for her release and for the right to see her children again. Sophia Dorothea's daughter, the Queen of Prussia, travelled to Hanover in 1725 to see her father, by then King George I of Great Britain; Sophia Dorothea, dressed even more carefully than usual, waited in vain every day at the window of her residence, hoping to see her daughter.

In the end, she seems only to have found comfort in eating. Her defences waned, she grew overweight due to lack of exercise and was frequently plagued by febrile colds and indigestion. In early 1726, she suffered a stroke; in August of that year she went to bed with a severe colic, and never rose again, refusing all food and treatment. Within a few weeks she grew emaciated. Sophia Dorothea died shortly before midnight on 13 November 1726 aged 60; her autopsy revealed a liver failure and gall bladder occlusion due to 60 gallstones. Her former husband placed an announcement in The London Gazette to the effect that the "Duchess of Ahlden" had died,[12] but forbade mourning in London or Hanover. He was furious when he heard that his daughter's court in Berlin wore black.[13]

Sophia Dorothea's funeral turned into a farce. Because the guards in Ahlden castle had no instructions, they placed her remains in a lead coffin and deposited them in the cellar. In January 1727 the order came from London to bury her without any ceremonies in the cemetery of Ahlden, which was impossible due to weeks of heavy rain. So the coffin was brought back to the cellar and covered in sand. It wasn't until May 1727 that Sophia Dorothea was buried, secretly and at night,[13] beside her parents in the Stadtkirche in Celle.[14][15][16] King George I of Great Britain, her former husband and gaoler, died four weeks later, while visiting Hanover.

Inheritance[]

Sophia Dorothea's parents seem to have believed to the last that their daughter would one day be released from prison. In January 1705, shortly before her father's death, he and his wife drew up a joint will, according to which their daughter would receive the estates of Ahlden, Rethem and Walsrode, extensive estates in France and Celle, the great fortune of her father and the legendary jewelry collection of her mother. Her father appointed Count Heinrich Sigismund von Bar as administrator of Sophia Dorothea's fortune; twelve years older than the princess and a handsome, highly educated and sensitive gentleman, Count von Bar and Sophia Dorothea shared old ties of affection. She named him as one of the main beneficiaries of her will, but unfortunately he died six years before her.[13]

Related history and trivia[]

- In 1698 Sophia Dorothea's former husband George Louis took office in the Electorate of Hanover. In 1701, the English Parliament passed the Act of Settlement, which declared Electress Sophia of Hanover the next Protestant successor to the English throne. In 1707, the Treaty of Union created the United Kingdom of England and Scotland and Queen Anne became the first Queen of Great Britain and Ireland. As Electress Sophia died a few weeks before Queen Anne's death in 1714, it was her son Elector George Louis who succeeded as King and moved to London. The personal union between Hanover and Great Britain lasted 123 years.

- Eleonore von dem Knesebeck (1655–1717), Sophia Dorothea's lady-in-waiting and close confidant, was imprisoned in 1695 in Scharzfels Castle in the borough of Herzberg am Harz. After two years of solitary confinement, she managed to escape on 5 November 1697 and was able to flee to Wolfenbüttel under the protection of Duke Anthony Ulrich. She left a unique document in the room of the tower where she was confined: all the walls and doors were written down to the last corner with charcoal and chalk. The texts (sacred poems in the style of contemporary church hymns), where accusations against her enemies at court and memoir-like prose pieces; all these were recorded for the Hanover archive files. Until her death, she denied the adulterous relationship between Sophia Dorothea and von Königsmarck.[17][18]

- The French adventurer, Marquis Armand de Lassay (1652–1738), later claimed in his memoirs that he had received no fewer than thirteen love letters from Sophia Dorothea but never showed any documents to anyone.[19]

- As the "uncrowned Queen of Great Britain", the life and tragic fate of Sophia Dorothea fascinated the imaginations of her contemporaries and of posterity. In 1804, Friedrich von Schiller had even planned a tragedy dedicated to her, called The Princess of Celle, but never completed it.[20]

- Sophia Dorothea's great-granddaughter Caroline Matilda of Great Britain, Queen consort of Denmark and Norway (1751–1775) shared her fate. After the Struensee affair in 1772, she was divorced from her husband, separated from her children and sent to Celle Castle, where she died three years later. In the crypt of the Stadtkirche St. Marien, both women are united in death.[21]

- The life story of Sophia Dorothea was recorded by Arno Schmidt in his novel Das steinerne Herz – Ein historischer Roman aus dem Jahre 1954 nach Christi, some scenes of which take place in Ahlden and – for one episode – Berlin. In the novel, Schmidt gradually inserts the story of the Princess of Ahlden into the narrative and mentions Ahlden House several times as a walking destination for the protagonists, who eventually find a treasure in Sophia Dorothea's estate and prosper from it.

Film[]

- Sophia Dorothea's affair and its tragic outcome is the basis of the 1948 British film Saraband for Dead Lovers. She was portrayed by Joan Greenwood.

References[]

- ^ Horric de Beaucaire 1884, p. 62.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Horric de Beaucaire 1884, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Leitner 2000, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Herman 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Hatton 1978, p. 55.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mijndert Bertram: Das Königreich Hannover – Kleine Geschichte eines vergangenen deutschen Staates(in German); Hannover: Hahn, 2003; ISBN 3-7752-6121-4

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hatton 1978, pp. 51–61.

- ^ From the reports of the English ambassador, Lord George Stepney.

- ^ Knochenfund am Landtag: Bringt DNA-Test Klarheit? (in German) in: Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung website (haz.de) [retrieved 9 August 2020].

- ^ Frederick the Great: Gedanken und Erinnerungen. Werke, Briefe, Gespräche, Gedichte, Erlasse, Berichte und Anekdoten (in German); Essen: Phaidon, 1996. ISBN 3-88851-167-4

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hatton 1978, pp. 60–64.

- ^ Michael L. Nash (9 February 2017). Royal Wills in Britain from 1509 to 2008. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-60145-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Leitner 2000, pp. 66–68.

- ^ The royal crypt and the grave slabs of the dukes of Braunschweig-Lüneburg in the town church of St. Marien Celle, with a leaflet illustrated with photos by Dietrich Klatt, Friedrich Kremzow and Ralf Pfeiffer, in DIN A5 format (4 pages) designed by Heide Kremzow, after: Dietrich Klatt: Little Art Guide Schnell & Steiner N° 1986, 2008.

- ^ Leslie Carroll (5 January 2010). Notorious Royal Marriages: A Juicy Journey Through Nine Centuries of Dynasty, Destiny, and Desire. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-15977-4.

- ^ Das Grab der Prinzessin von Ahlden (in German) in: knerger.de [retrieved 9 August 2020].

- ^ Kuhn 1992, p. 281.

- ^ Henrike Leonhardt: Flucht der Eleonore v. d. Knesebeck [05.11.1697] (in German) [retrieved 9 August 2020].

- ^ Leitner 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Georg Ruppelt: Schiller in Hanover in: schillerjahr2005.de [dead link, last access date 24 December 2008].

- ^ Kuhn 1992, p. 412.

Bibliography[]

- Ahlborn, Luise: Zwei Herzoginnen (in German). Janke ed., Berlin 1903 (published under the pseudonym "Louise Haidheim").

- Hatton, Ragnhild (1978). George I: Elector and King. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 51–64. ISBN 0-500-25060-X.

- Herman, Eleanor (2006). Sex with the Queen. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-084673-9.

- Haag, Eugène; Haag, Émile; Bordier, Henri Léonard (1877). La France Protestante (in French). Paris: Sandoz et Fischbacher.

- Hisserich, Walther: Die Prinzessin von Ahlden und Graf Königsmarck in der erzählenden Dichtung. Ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden Literaturgeschichte (in German). Roether, Darmstadt 1906, DNB 574013725, OCLC 681273154 (Dissertation University of Rostock 1906, 50 pages online, HathiTrust Digital Library,2010. MiAaHDL, limited search only, use with USA proxy possible).

- Horric de Beaucaire, Charles Prosper Maurice (1884). Une mésalliance dans la maison de Brunswick, 1665–1725, Éléonore Desmier d'Olbreuze, duchesse de Zell (in French). Paris: Sandoz et Fischbacher.

- Hunold, Christian Friedrich (1705). Der Europäischen Höfe Liebes- und Heldengeschichte (in German). Hamburg: Gottfried Liebernickel.

- Jordan, Ruth: Sophie Dorothea. Constable Books, London 1971.

- Köcher, Adolf (1892), "Sophie Dorothea (Kurprinzessin von Hannover)", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), 34, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 671–674

- Kuhn, Annette (1992). Die Chronik der Frauen (in German). Dortmund: Chronik. ISBN 978-3611001956.

- Leister, Dieter-Jürgen: Bildnisse der Prinzessin von Ahlden (in German), in: Niederdeutsche Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte, vol. 9, 1970, pp. 169–178.

- Leitner, Thea (2000). Skandal bei Hof. Frauenschicksale an europäischen Königshöfen (in German). Munich: Piper. ISBN 3-492-22009-6.

- Leslie, Doris: The Rebel Princess. Heinemann, London 1970.

- Mason, A. E. W.: Königsmarck. Hodder & Stoughton, London 1951 (Nachdr. d. Ausg. London 1938).

- Morand, Paul: Sophie Dorothea von Celle. Die Geschichte eines Lebens und einer Liebe ("Ci-gît Sophie-Dorothée de Celle", 1968) (in German). 2nd edition L. Brandt, Celle 1979, ISBN 3-9800226-0-9.

- Öztanil, Guido Erol: "All’ dies gleicht sehr einem Roman". Liebe, Mord und Verbannung: Die Prinzessin von Ahlden (1666–1726) und einige Seitenblicke auf die Geschichte des Fleckens Ahlden (in German). Walsrode 1994, OCLC 258420524

- Schnath, Georg: Der Königsmarck-Briefwechsel. Korrespondenz der Prinzessin Sophie Dorothea von Hannover mit dem Grafen Philipp Christoph Konigsmarck 1690 bis 1694 (In German) (Quellen und Darstellungen zur Geschichte Niedersachsens; vol. 51). Lax, Hildesheim 1952 (critical complete edition in Regestenform).

- Scholz, Carsten Scholz; Seelke, Anja: Eine Liebe in Zeiten des Despotismus. Sophie Dorothea von Hannover und Philipp Christoph von Königsmarck in alten und zwei neuen Porträts. (in German) In: Celler Chronik 23. Celle 2016.

- Singer, Herbert: Die Prinzessin von Ahlden. Verwandlungen einer höfischen Sensation in der Literatur des 18. Jahrhunderts (in German). In: Euphorion. Zeitschrift für Literaturgeschichte, vol. 49 (1955), pp. 305–334, ISSN 0014-2328.

- von Pöllnitz, Karl Ludwig (1734). Der Herzogin von Hannover geheime Geschichte (Histoire Secrette de la Duchesse d'Hannovre Epouse de Georges Premier Roi de la grande Bretagne (...), 1732) (in German). Stuttgart. Note: published without naming the author.

- von Ramdohr, Friedrich Wilhelm Basilius: Essai sur l'histoire de la princesse d' Ahlen, épouse du prince électoral d'Hanovre (...), Suard's Archives Littéraires 3, pp. 158–204, Paris and Tübingen 1804 (without mentioning the author);[1] author identified according to source[2] dated 1866 and by C. Haase[3] in 1968.

- Weir, A. (2002). Britain's Royal Families – The Complete Genealogy.

- Wilkins, William H.: The Love of an Uncrowned Queen. Sophie Dorothea, consort of George I. and her correspondence with Philip Christopher Count Königsmarck. Hutchinson, London 1900.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sophia Dorothea". Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 418. This work in turn cites:

- W. F. Palmblad, ed., Briefwechsel des Grafen Königsmark and der Prinzessin Sophie Dorothea von Celle (Leipzig, 1847)

- A. F. H. Schaumann, Sophie Dorothea Prinzessin von Ahlden

- A. F. H. Schaumann, Kurfürstin Sophie von Hannover (Hanover, 1878)

- C. L. von Pöllnitz, Histoire secrette de la duchesse d'Hanovre (London, 1732)

- W. H. Wilkins, The Love of an Uncrowned Queen (London, 1900)

- A. Köcher, "Die Prinzessin von Ahlden," in the Historische Zeitschrift (Munich, 1882)

- Vicomte H. de Beaucaire, Une Mésalliance dans la maison de Brunswick (Paris, 1884)

- Alice Drayton Greenwood, Lives of the Hanoverian Queens of England, vol. i (1909)

Fiction novels[]

- Anthony Ulrich, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel: Römische Octavia (in German). Nürnberg 1685–1707, 7 vols.; Brunswick 1712.

- Hermann Schiff: Die Prinzessin von Ahlden oder Drei Prophezeiungen; ein Roman der Weltgeschichte (in German). Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 1855.

- Theodor Hemsen: Die Prinzessin von Ahlden. Historischer Roman (in German). Rümpler ed., Hannover 1869 (6 Bde.).

- Paul Burg: Des galanten Grafen Königsmarck letzte Liebes-Abenteuer. Ein Rokoko-Roman (in German). Stern Bücher ed. (Koch & Co.), Leipzig 1922.

- Helen Simpson: Saraband for dead Lovers. Tauchnitz, London 1935.

- Eleanor Hibbert: The Princess of Celle. Putnam Books, New York 1985, ISBN 0-399-13070-5 (reprint of the London 1967 edition; published under the pseudonym "Jean Plaidy").

- Anny Wienbruch: Die ungekrönte Königin. Sophie Dorothea, die Gefangene von Ahlden (in German). St.-Johannis-Druckerei ed., Lahr-Dinglingen 1976, ISBN 3-501-00080-4.

- Helene Lehr: Sophia Dorothea. Die verhängnisvolle Liebe der Prinzessin von Hannover; Roman (in German). Droemer Knaur, München 1994, ISBN 3-426-60141-9.

- John Veale: Passion Royal. A novel. Book guild Publ., Lewes, Sussex 1997, ISBN 1-85776-157-X.

- Dörte von Westernhagen: Und also lieb ich mein Verderben. Roman (in German). Wallstein ed., Göttingen 1997, ISBN 3-89244-246-0.

- Heinrich Thies: Die verbannte Prinzessin. Das Leben der Sophie Dorothea; Romanbiografie (in German). 2 edition Klampen ed., Springe 2007, ISBN 978-3-933156-93-8.

- Sargon Youkhana: Die Affäre Königsmarck. Historischer Roman. (in German). Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-548-60763-4.

- ^ Essai sur l'histoire de la princesse d' Ahlen (in French), retrieved 09 August 2020

- ^ Historischer Verein für Niedersachsen: Katalog der Bibliothek des Historischen Vereins für Niedersachsen (in German), Historischer Verein für Niedersachsen, p. 15, entry n°. 1289. Ph.C. Göhmann, Hanover 1866.

- ^ Carl Haase: Neues über Basilius von Ramdohr (in German). In: Niedersächsisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte vol. 40 (1968), p. 172 PDF.

- 1666 births

- 1726 deaths

- New House of Lüneburg

- People from Celle

- Electoral Princesses of Hanover

- George I of Great Britain