Soylent Green

| Soylent Green | |

|---|---|

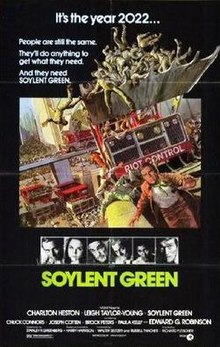

Theatrical release poster by John Solie | |

| Directed by | Richard Fleischer |

| Screenplay by | Stanley R. Greenberg |

| Based on | Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison |

| Produced by | Walter Seltzer Russell Thacher |

| Starring | Charlton Heston Leigh Taylor-Young Chuck Connors Joseph Cotten Brock Peters Paula Kelly Edward G. Robinson |

| Cinematography | Richard H. Kline |

| Edited by | Samuel E. Beetley |

| Music by | Fred Myrow |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $3.6 million (rentals)[1] |

Soylent Green is a 1973 American ecological dystopian thriller film directed by Richard Fleischer, and starring Charlton Heston, Leigh Taylor-Young and Edward G. Robinson in his final film role. Loosely based on the 1966 science fiction novel Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison, the film combines police procedural and science fiction genres, the investigation into the murder of a wealthy businessman and a dystopian future of dying oceans and year-round humidity, due to the greenhouse effect, resulting in pollution, poverty, overpopulation, euthanasia and depleted resources.[2] In 1973, it won the Nebula Award for Best Dramatic Presentation and the Saturn Award for Best Science Fiction Film.

Plot[]

By the year 2022,[3] the cumulative effects of overpopulation, pollution and an apparent climate catastrophe have caused severe worldwide shortages of food, water and housing. There are 40 million people in New York City alone, where only the city's elite can afford spacious apartments, clean water and natural food (at horrendously high prices, with a jar of strawberry jam fetching $150). The homes of the elite are fortressed, with private security, bodyguards for their tenants, and usually include concubines (who are referred to as "furniture" and serve the tenants as slaves).

Within the city live NYPD detective Frank Thorn and his aged friend Sol Roth, a highly intelligent former college professor and police analyst (referred to as a "Book"). Roth remembers the world when it had animals and real food; he has a small library of reference materials to assist Thorn. Thorn is tasked with investigating the murder of the wealthy and influential William R. Simonson, a board member of the Soylent Corporation, which he suspects was an assassination.

The Soylent Corporation produces the communal food supply of half of the world, and distributing the homonymous brand of wafers, including "Soylent Red" and "Soylent Yellow". Their latest product, "Soylent Green", a more nutritious variant, is advertised as being made from ocean plankton, but is in short supply. As a result of the weekly supply chain and distribution bottlenecks, the hungry masses regularly riot when supply runs out, and are brutally removed from the streets by means of "Scoops" – police crowd control vehicles that literally "scoop" the rioters from the street with large hydraulic shovels.

With the help of Simonson's concubine Shirl (with whom Thorn begins a sexual relationship), his investigation leads to a priest that Simonson had visited shortly before his death. Because of the sanctity of the confessional, the nearly overcome priest is only able to hint at the contents of the confession (before he himself is murdered). By order of the governor, Thorn is instructed to end the investigation by his immediate superiors, but because of his concern for losing his job to higher superiors if he quits the case, and the fact that he is being followed by an unknown stalker, he continues forward. He is soon attacked while working during a riot, by the same assassin who killed Simonson, but the killer is crushed by the hydraulic shovel of a police crowd control vehicle.

In researching the case for Thorn, Roth brings two volumes of "Soylent Oceanographic Survey Report, 2015–2019" taken by Thorn from Simonson's apartment, to the team of other Books at the Supreme Exchange. After analysis, the Books confirm that the oceanographic report reveals that the oceans are dying, and can no longer produce the plankton from which "Soylent Green" is made. The reports also reveal that "Soylent Green" is being produced from the remains of the dead and the imprisoned, obtained from heavily guarded waste disposal plants outside the city. The Books further reveal that Simonson's murder was ordered by his fellow Soylent Corporation board members, knowing he was increasingly troubled by the truth, and the fear that he might talk.

On hearing the truth, Roth is so shaken he decides to "return to the Home of God" and seeks assisted suicide at a government clinic. Returning to the apartment, Thorn finds a message left by Roth, and rushes to stop him but arrives too late to save Roth's life. Thorn is mesmerized by the euthanasia process's visual and musical montage—long-gone forests, wild animals, rivers and ocean life, having never before seen these sights. Before dying, Roth whispers what he has learned to Thorn, and in his last living act, begs him to find proof, bring it to the Supreme Exchange, so they can take the information to the Council of Nations to take action.

Thorn boards a truck transporting Roth's body and the bodies from the euthanasia center to a waste disposal plant, where he witnesses human corpses being converted into Soylent Green. Horrified, Thorn is spotted and escapes. As he is making his way back to the Supreme Exchange, he is ambushed. Finding refuge in a church, he kills his attackers, but is seriously wounded in the gun battle. As Thorn is tended to by paramedics, he urges Lt. Hatcher to spread the truth he has discovered, and initiate proceedings against the company. While being taken away, Thorn shouts out to the surrounding crowd, "Soylent Green is people!"

Cast[]

- Charlton Heston as Thorn

- Leigh Taylor-Young as Shirl

- Chuck Connors as Fielding

- Joseph Cotten as Simonson

- Brock Peters as Hatcher

- Paula Kelly as Martha

- Edward G. Robinson as Sol Roth

- Stephen Young as Gilbert

- Mike Henry as Kulozik

- Lincoln Kilpatrick as The Priest

- Roy Jenson as Donovan

- Leonard Stone as Charles

- Whit Bissell as Santini

- Celia Lovsky as the Exchange Leader

- Dick Van Patten as Usher #1

Production[]

The screenplay was based on Harry Harrison's novel Make Room! Make Room! (1966), set in the year 1999 with the theme of overpopulation and overuse of resources leading to increasing poverty, food shortages and social disorder. Harrison was contractually denied control over the screenplay and was not told during negotiations that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was buying the film rights.[4] He discussed the adaptation in Omni's Screen Flights/Screen Fantasies (1984), noting the "murder and chase sequences [and] the 'furniture' girls are not what the film is about – and are completely irrelevant" and answered his own question, "Am I pleased with the film? I would say fifty percent".[4][5]

While the book refers to "soylent steaks", it makes no reference to "Soylent Green", the processed food rations depicted in the film. The book's title was not used for the movie on grounds that it might have confused audiences into thinking it a big-screen version of Make Room for Daddy.[6]

This was the 101st and last movie in which Edward G. Robinson appeared; he died of bladder cancer twelve days after the completion of filming, on January 26, 1973. Robinson had previously worked with Heston in The Ten Commandments (1956) and the make-up tests for Planet of the Apes (1968). In his book The Actor's Life: Journal 1956–1976, Heston wrote "He knew while we were shooting, though we did not, that he was terminally ill. He never missed an hour of work, nor was late to a call. He never was less than the consummate professional he had been all his life. I'm still haunted, though, by the knowledge that the very last scene he played in the picture, which he knew was the last day's acting he would ever do, was his death scene. I know why I was so overwhelmingly moved playing it with him".[7]

The film's opening sequence, depicting America becoming more crowded with a series of archive photographs set to music, was created by film maker Charles Braverman. The "going home" score in Roth's death scene was conducted by Gerald Fried and consists of the main themes from Symphony No. 6 ("Pathétique") by Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 6 ("Pastoral") by Beethoven and the Peer Gynt Suite ("Morning Mood" and "Åse's Death") by Edvard Grieg. A custom cabinet unit of the early arcade game Computer Space was used in Soylent Green and is considered to be the first video game appearance in a film.[8]

Critical response[]

The film was released April 19, 1973, and met with mixed reactions from critics.[9] Time called it "intermittently interesting", noting that "Heston forsak[es] his granite stoicism for once" and asserting the film "will be most remembered for the last appearance of Edward G. Robinson.... In a rueful irony, his death scene, in which he is hygienically dispatched with the help of piped-in light classical music and movies of rich fields flashed before him on a towering screen, is the best in the film".[10] New York Times critic A. H. Weiler wrote "Soylent Green projects essentially simple, muscular melodrama a good deal more effectively than it does the potential of man's seemingly witless destruction of the Earth's resources"; Weiler concludes "Richard Fleischer's direction stresses action, not nuances of meaning or characterization. Mr. Robinson is pitiably natural as the realistic, sensitive oldster facing the futility of living in dying surroundings. But Mr. Heston is simply a rough cop chasing standard bad guys. Their 21st-century New York occasionally is frightening but it is rarely convincingly real".[9]

Roger Ebert gave the film three stars out of four, calling it "a good, solid science-fiction movie, and a little more".[11] Gene Siskel gave the film one-and-a-half stars out of four and called it "a silly detective yarn, full of juvenile Hollywood images. Wait 'til you see the giant snow shovel scoop the police use to round up rowdies. You may never stop laughing".[12] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety wrote, "The somewhat plausible and proximate horrors in the story of 'Soylent Green' carry the Russell Thacher-Walter Seltzer production over its awkward spots to the status of a good futuristic exploitation film".[13] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "a clever, rough, modestly budgeted but imaginative work".[14] Penelope Gilliatt of The New Yorker was negative, writing, "This pompously prophetic thing of a film hasn't a brain in its beanbag. Where is democracy? Where is the popular vote? Where is women's lib? Where are the uprising poor, who would have suspected what was happening in a moment?"[15]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 72% rating, based on 39 reviews, with an average rating of 6.10/10.[16] A German film encyclopedia notes "If you want, you can see a thrilling crime thriller in this film. By means of brutally resonant scenes, however, the director makes clear a far deeper truth [...] Soylent Green must thus be understood as a metaphor. It is the radical image of the self-consuming madness of capitalist mode of production. The necessary consequences of the reification of 'human material' to the point of self-destruction are forcefully brought home to the viewer".[17]

Awards and honors[]

- Winner Best Science Fiction Film of Year – Saturn Award, Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films (Richard Fleischer, Walter Seltzer, Russell Thacher)

- Winner Grand Prize – Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival (Richard Fleischer)

- Nominee Best Film of Year (Best Dramatic Presentation) – Hugo Award (Richard Fleischer, Stanley Greenberg, Harry Harrison)

- Winner Best Film Script of Year (Best Dramatic Presentation) – Nebula Award, Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (Stanley Greenberg, Harry Harrison)

- "Soylent Green is people!" is ranked 77th on the American Film Institute's list AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes.

Home media[]

Soylent Green was released on Capacitance Electronic Disc by MGM/CBS Home Video and later on LaserDisc by MGM/UA in 1992 (ISBN 0-7928-1399-5, OCLC 31684584).[18] In November 2007, Warner Home Video released the film on DVD concurrent with the DVD releases of two other science fiction films; Logan's Run (1976), a film that covers similar themes of dystopia and overpopulation, and Outland (1981).[19] A Blu-ray Disc release followed on March 29, 2011.

See also[]

- Soylent (meal replacement), a brand of meal replacement products whose creator was inspired by the book and film to use that name

- Cloud Atlas (film), a 2012 film also depicting a future society where workers are fed with human remains

- Tender is the Flesh, a 2020 dystopian novel by Agustina Bazterrica in which humans are farmed for their meat

References[]

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973". Variety. January 9, 1974. p. 19.

- ^ Shirley, John (September 23, 2007). "Soylent Green: An Appreciation 34 Years Too Late". Locus Online. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ Kooser, Amanda (January 13, 2022). "Soylent Green predicted 2022 as a dystopian hellscape. Did the movie get it right?". CNET. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Stafford, Jeff (July 28, 2003). "Soylent Green". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ Peary, Danny, ed. (1984). Omni's Screen Flights/Screen Fantasies. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19202-9.

- ^ Harrison, Harry (1984). "A Cannibalised Novel Becomes Soylent Green". Omni's Screen Flights/Screen Fantasies. Ireland On-Line. Retrieved September 7, 2009.

- ^ Heston, Charlton (1978). Alpert, Hollis (ed.). The Actor's Life: Journal 1956–1976. E. P. Dutton. p. 395. ISBN 0-525-05030-2.

- ^ Goldberg, Marty; Vendel, Curt (2012). Atari Inc: Business Is Fun. Syzygy Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-9855974-0-5. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Weiler, A. H. (April 20, 1973). "Screen: 'Soylent Green'". The New York Times. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ "Cinema: Quick Cuts". Time. Vol. 101, no. 18. April 30, 1973. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (April 27, 1973). "Soylent Green". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (May 1, 1973). "Scorpio & Soylent". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 5.

- ^ Murphy, Arthur D. (April 18, 1973). "Soylent Green". Variety. p. 22.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (April 18, 1973). "Grim Future in 'Soylent Green'". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Gilliatt, Penelope (April 28, 1973). "The Current Cinema: Hungry?". The New Yorker. p. 131.

- ^ "Soylent Green (1973)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ Schneider, Irmela; Thomsen, Christian W., eds. (1989). Lexikon der britischen und amerikanischen Spielfilme in den Fernsehprogrammen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1954–1985 (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin: Spiess. p. 642. ISBN 978-3-89166-064-5.

- ^ "Soylent green / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc". Miami University Libraries. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ Hendrix, Grady (November 27, 2007). "The Future Is Then". The New York Sun. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

Further reading[]

- Smith, Wesley J. (January 16, 2022). "What 1973's Soylent Green Accurately Predicted about 2022". National Review. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- Sokol, Tony (January 7, 2022). "Soylent Green Predicted 2022, Including Impossible Meat Substitutes". Den of Geek. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- Osteried, Peter (January 15, 2022). "Bedingt prophetisch". Golem.de (in German). Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- Küveler, Jan (January 3, 2022). "Soylent Green: Die Gegenwart holt die Ökodystopie ein". Die Welt (in German). Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- Eckner, Constantin (January 12, 2022). "Ökodystopie "Soylent Green" – Prognosen fürs Katastrophenjahr 2022". Deutschlandfunk Kultur (in German). Retrieved January 17, 2022.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Soylent Green |

- 1973 films

- English-language films

- 1970s dystopian films

- 1970s science fiction thriller films

- American dystopian films

- American films

- American neo-noir films

- American science fiction thriller films

- Climate change films

- 1970s English-language films

- Environmental films

- Euthanasia

- Fictional food and drink

- Films about cannibalism

- Films about famine

- Films based on science fiction novels

- Films directed by Richard Fleischer

- Films set in 2022

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in the future

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Nebula Award for Best Script-winning works

- Overpopulation fiction

- Procedural films