Space Oddity

It has been suggested that Ragazzo solo, ragazza sola be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2021. |

| "Space Oddity" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

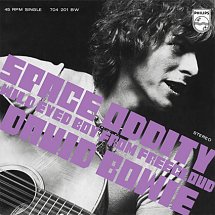

Cover to the 1969 Dutch/Italian release | ||||

| Single by David Bowie | ||||

| from the album David Bowie (Space Oddity) | ||||

| B-side |

| |||

| Released | 11 July 1969 | |||

| Recorded | 20 June 1969 | |||

| Studio | Trident, London | |||

| Genre | Psychedelic folk[1] | |||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | ||||

| Songwriter(s) | David Bowie | |||

| Producer(s) | Gus Dudgeon | |||

| David Bowie singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

"Space Oddity"

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Space Oddity" on YouTube | ||||

"Space Oddity" is a song written and recorded by English singer-songwriter David Bowie. It was first released as a 7-inch single on 11 July 1969 before appearing as the opening track of his second studio album, David Bowie. It became one of Bowie's signature songs and one of four of his songs to be included in The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll.[2]

Inspired by Stanley Kubrick's film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968),[3] with a title that plays on the film's title,[4] the song is about the launch into space of Major Tom, a fictional astronaut, and was released during a period of great interest in space flight. The United States' Apollo 11 mission would launch five days later and would become the first manned Moon landing another five days after that.[5] The lyrics have also been seen to lampoon the British space programme,[6] which was, and still is, an unmanned project. Bowie revisited his Major Tom character in the 1980 lead-single "Ashes to Ashes" from Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) and the 1995 single "Hallo Spaceboy" from Outside, the third and final single released from that album. In addition, Major Tom possibly influenced the music video for "Blackstar", released in 2015 off of Bowie's final album of the same name.

Written in the key of C major,[7] "Space Oddity" was Bowie's first single to chart in the UK. It reached the top five on its initial release and received the 1970 Ivor Novello Special Award for Originality.[8] His self-titled second album was renamed after the track for its 1972 rerelease by RCA Records and became known by this name. In 1975, upon rerelease as part of a maxi-single, the song became Bowie's first UK No. 1 single.[9]

In 2013, the song gained renewed popularity following its recording by Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who performed the song (with slightly revised lyrics) while aboard the International Space Station, and therefore became the first music video shot in space. In January 2016, the song reentered singles charts around the world following Bowie's death, which included becoming Bowie's first single to top the French Singles Chart.[10]

Background and writing[]

After a string of unsuccessful singles, David Bowie released his music hall-influenced self-titled debut studio album through Deram Records in 1967. It was a commercial failure and did little to gain him notice, becoming his last release for two years.[11][12] Around this time he also acquired a new manager, Kenneth Pitt.[13] In 1968, Bowie began a relationship with dancer Hermione Farthingale.[14] With her and guitarist John Hutchinson, he formed a group called Feathers; with Bowie on acoustic guitar, the trio gave a small number of concerts between September 1968 and early 1969 combining folk, Merseybeat, poetry and mime.[15] Bowie's relationship with Farthingale lasted until February 1969.[16] After the commercial failure of David Bowie, Pitt authorised a promotional film in an attempt to introduce Bowie to a larger audience. The film, Love You till Tuesday, went unreleased until 1984,[17] with it marking the end of Pitt's mentorship to Bowie.[16]

By the end of 1968, Bowie had begun to feel alienation from his career. Knowing Love You till Tuesday didn't have a guaranteed audience and wouldn't feature any new material, Pitt asked Bowie to write something new, specifically "a very special piece of material that would dramatically demonstrate David's remarkable inventiveness and would probably be the high spot of the production."[18][19] With this in mind, Bowie wrote "Space Oddity", a tale about a fictional astronaut named Major Tom.[20] Its title and subject matter were influenced by Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey,[21] which premiered in May 1968.[22] Bowie recalled: "I went stoned out of my mind to see the movie and it really freaked me out, especially the trip passage."[23] Biographer Marc Spitz states that the scene in the film in which an astronaut communicates with his daughter on her birthday, where he says "Tell mama that I telephoned" before ingesting a "stress pill", is the scene that most likely inspired Bowie rather than the film's opening or ending.[24] The director of Love You till Tuesday, Malcolm Thompson, later claimed he and his girlfriend Susie Mercer contributed to the songwriting process.[18] Bowie's break-up with Farthingale affected Bowie deeply.[20] He later said, "It was Hermione who got me writing for and on a specific person." Spitz states that Bowie's feeling of loneliness and heartache following the break-up would inspire "Space Oddity".[25]

Recording and release[]

Three primary studio versions of "Space Oddity" exist: an early version recorded in February 1969, the album version recorded that June (edited for release as a single), and a 1979 rerecording.

The early studio version of "Space Oddity" was recorded on 2 February 1969, at Morgan Studios, Willesden, London, for Bowie's promotional film Love You till Tuesday.[26] Bowie and his then musical partner John Hutchinson shared lead vocals and played acoustic guitars, with Bowie adding ocarina and a Stylophone.[27] The lineup on the first studio version also included Colin Wood (Hammond organ and Mellotron), Dave Clague (bass), and Tat Meager (drums).[28] This recording became commercially available in 1984, on a belated VHS release of the film and accompanying soundtrack album. It subsequently appeared on the compilation albums London Boy (full-length version, 4:31) and The Deram Anthology 1966–1968.

In June 1969, after Bowie's split from record label Deram, his manager, Kenneth Pitt, negotiated a one-album deal (with options for a further one or two albums) with Mercury Records and its UK subsidiary, Philips.[29] Mercury executives had heard an audition tape that included a demo of "Space Oddity" recorded by Bowie and Hutchinson in spring 1969. Next Bowie tried to find a producer. George Martin turned the project down,[29] while Tony Visconti liked the album demo-tracks, but considered the planned lead-off single, "Space Oddity", a 'cheap shot' at the impending Apollo 11 space mission. Visconti decided to delegate its production to Gus Dudgeon.[30]

The album version of "Space Oddity" (5:15) was recorded at Trident Studios on 20 June 1969 (with overdubs a few days later) and used the in-house session player Rick Wakeman (Mellotron), who was later to achieve fame with the progressive rock band Yes, as well as Mick Wayne (guitar), Herbie Flowers (bass), Terry Cox (drums),[31] with Paul Buckmaster (who went on the have a hit with 'Love at first Sight', an instrumental version of Serge Gainsbough's "Je T Aime, Moi Non Plus") orchestrating the strings section. (Bowie sang lead and harmony vocals and played acoustic guitar and the Stylophone.[32] Differing edits of the album version were released as singles, in the UK (mono, 4:33), the US (mono and stereo, 3:26), and several other countries. The original UK mono single edit was included on Re:Call 1, part of the Five Years (1969–1973) box set, in 2015.

The song was promoted in advertisements for the Stylophone, played by Bowie on the record and heard in the background during the opening verse. The single was not played by the BBC until after the Apollo 11 crew had safely returned;[33] after this slow start, the song reached No. 5 in the UK Singles Chart. In the US, it stalled at 124.

On 2 October 1969, Bowie performed the song for an episode of Top of the Pops. However, this was recorded separate from the main audience. The performance was shown on 9 October the following week, and repeated on 16 October.

The release was timed by the record company to align with the Moon landing, and so Bowie was considered for a time a novelty act, especially since he would not have another hit for three years.[34]

Mogol wrote Italian lyrics for the song, and Bowie recorded a new vocal in December 1969, releasing the single "Ragazzo solo, ragazza sola" ("Lonely Boy, Lonely Girl") in Italy.[35]

Upon its rerelease as a single in 1973, "Space Oddity" reached No. 15 on the Billboard Chart and became Bowie's first hit single in the United States; in Canada, it reached No. 16.[36] This success was then used to support RCA's September 1975 UK reissue, which gave Bowie his first No. 1 single in the UK Singles Chart in November that year. It spent two weeks at the top of that chart.[37]

Bowie recorded a stripped-down, acoustic version of "Space Oddity" in late 1979,[38] which was issued in February 1980 as the B-side of "Alabama Song". The 1979 recording was released, in a remixed form, in 1992 on the Rykodisc reissue of Bowie's Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) album, and it was rereleased on Re:Call 3, part of the A New Career in a New Town (1977–1982) compilation, in 2017.[39]

On 20 July 2009, the single was reissued on a digital EP that features the original UK and US mono single edits, a subsequent US stereo single edit, and the 1979 rerecording, as well as stems that allow listeners to remix the song. This release coincided with the 40th anniversary of the song and the Apollo 11 Moon landing.

The 50th anniversary of the single was marked on 12 July 2019 by the release, on digital and vinyl singles, of a new remix of the song by Tony Visconti. The vinyl version, issued in a box set, also included the original UK mono single edit.[40][41]

Demo versions[]

There were also several demos recorded in early 1969, several of which have since had an official commercial release.

An early demo was recorded in approximately late January 1969.[42] This demo differs greatly from the album version, with only an acoustic guitar and Stylophone present as instruments. The vocals in this demo were provided by Bowie and Hutchinson. Hutchinson played the acoustic guitar, while Bowie played the Stylophone.[42] The demo remained officially unreleased for more than 40 years until it appeared on the 2009 two-CD special edition of the album David Bowie. It made its vinyl debut in May 2019 on a box set titled Clareville Grove Demos.[43]

Two even earlier demos of "Space Oddity", including a fragment that may be the first recorded demo of the song, were released for the first time in April 2019, on Spying Through a Keyhole, a vinyl box set.[44]

Bowie and Hutchinson recorded another demo version in approximately mid-April 1969.[32] That recording appeared, with edits, as the opening track on the 1989 box set Sound + Vision. (The compilation also saw the first appearance on CD of the original "Space Oddity" single's B-side, "Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud".) It was released in unedited form, on a vinyl album titled The 'Mercury' Demos, in June 2019.[45]

All of these demo recordings and one other, previously unreleased demo of the song were included in the 5-CD boxed set Conversation Piece, released in November 2019.[46]

Accolades[]

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock and Roll Hall of Fame | United States | "The Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll"[47] | 2004 | * |

| VH1 | United States | "100 Greatest Rock Songs"[48] | 2000 | 60 |

| Pitchfork | United States | "The 200 Best Songs of the 1960s"[49] | 2016 | 48 |

| NME | United Kingdom | "Greatest No1 Singles In History"[50] | 2012 | 26 |

| Channel 4 and The Guardian | United Kingdom | "The Top 100 British Number 1 Singles"[51] | 1997 | 27 |

(*) designates unordered lists.

Live versions[]

Bowie played the song for the BBC's Johnny Walker Lunchtime Show on 22 May 1972. This was broadcast in early June 1972 and eventually released on Bowie at the Beeb in 2000.[52] A version recorded at Santa Monica Civic Auditorium on 20 October 1972 was first released on Santa Monica '72, before becoming officially available in 2008 on Live Santa Monica '72.[53] A live performance recorded at the Hammersmith Odeon, London, on 3 July 1973 was released on Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture in 1983.[54] A July 1974 live performance was released on the 2005 reissue of David Live.[55] A September 1974 live performance (previously available on the unofficial album A Portrait in Flesh) was released in 2017 on Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles '74).[56] A concert performance recorded on 12 September 1983 was included on the live album Serious Moonlight (Live '83), which was part of the 2018 box set Loving the Alien (1983–1988) and was released separately the following year. The filmed performance appears on the concert video Serious Moonlight (1984). Bowie effectively retired the song from live performances during his 1990 Sound+Vision Tour, playing the song on only a handful of occasions afterwards, most notably closing his 50th birthday party concert in January 1997 with a solo performance of the song.[57]

Music videos[]

On 6 February 1969, a video for the original version of the song was filmed and later appeared in the film Love You till Tuesday.

In December 1972, Mick Rock shot a video of Bowie miming to the June 1969 recording of the song, during the sessions for Aladdin Sane. The resulting music video was used to promote the 1973 US reissue of the "Space Oddity" single on RCA.[58]

A promotional video of the 1979 version debuted in the UK on Kenny Everett's New Year's Eve Show on 31 December 1979.[38] A music video made the following year for "Ashes to Ashes" used many of the same sets, solidifying the connection between the two songs. (Both videos were directed by Bowie and David Mallet.[59])

A fourth video was created for the 2019 remix of the song that year, as a promotion for the Conversation Piece box set. Directed by Tim Pope, the video combines footage from Bowie's 50th birthday concert in Madison Square Garden and backdrop footage shot by choreographer Édouard Lock for the Sound+Vision Tour in 1990.[60] The video premiered at the Kennedy Space Center and Times Square before being uploaded to YouTube hours later.[61]

Track listing[]

All songs written by David Bowie.

|

Disc 1

Disc 2

|

Personnel[]

Credits apply to the 1969 original release:[42]

Musical

- David Bowie – vocals, 12-string acoustic guitar, Stylophone, handclaps

- Mick Wayne – lead guitar

- Herbie Flowers – bass guitar

- Terry Cox – drums

- Paul Buckmaster – string arrangement

- Tony Visconti – flutes, woodwinds

- Rick Wakeman – Mellotron

Technical

- Gus Dudgeon – producer

Charts and certifications[]

Weekly charts[]

|

Year-end charts[]

Certifications[]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chris Hadfield version[]

In May 2013, Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, commander of Expedition 35 to the International Space Station, recorded a video of the song on the space station which went viral and generated a great deal of media exposure.[94] It was the first music video ever shot in space.[95] Filmed at the end of his time at the station, Hadfield sang and played guitar, while the backing track was produced and mixed on Earth by Joe Corcoran with a piano arrangement by multi-instrumentalist Emm Gryner, who previously worked with Bowie during his 1999–2000 concert tours; Gryner was quoted as saying she was "so proud to be a part of it".[96] The lyrics were somewhat altered; instead of losing communication with ground control and presumably being lost in space as a result, Major Tom successfully receives his orders to land and does so safely, reflecting Hadfield's imminent return from his final mission on the Station. Hadfield announced the video on his Twitter account, writing, "With deference to the genius of David Bowie, here's Space Oddity, recorded on Station. A last glimpse of the World." Bowie was also thanked in the ending credits.[97] Bowie's social media team responded to the video, tweeting back to Hadfield, "Hallo Spaceboy..."[98] and would later call the cover "possibly the most poignant version of the song ever created".[99][100]

The performance was the subject of a piece by Glenn Fleishman in The Economist on 22 May 2013 analyzing the legal implications of publicly performing a copyrighted work of music while in earth orbit.[101] The song is the only one of Bowie's for which Bowie did not own the copyright. Bowie's publisher granted Hadfield a license to the song for only one year.[102] Due to the expiry of the one-year licence, the official video was taken offline on 13 May 2014,[103] despite Bowie's explicit wishes that the publisher grant Hadfield a license at no charge to record the song and produce the video.[102] Following a period of negotiations, the video was restored to YouTube on 2 November 2014 with a two-year licence agreement in place.[104]

Nicholas Pegg offers unanimous praise to the video, writing: "Breathtakingly beautiful and extraordinarily moving, it offers a rare opportunity to deploy that overused adjective "awesome" with complete justification."[96]

See also[]

- "Ashes to Ashes" (David Bowie song)

- "Hallo Spaceboy"

- "Blackstar" (song)

- "Major Tom (Coming Home)" – A 1983 song by Peter Schilling written as a retelling of "Space Oddity".

- "Rocket Man" (song)

References[]

- ^ Beaumont, Mark (12 January 2016). "Life Before Ziggy – Remembering David Bowie's Early Years". NME. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ "Experience The Music: One Hit Wonders and The Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "David Bowie: 30 Essential Songs". Rolling Stone. 11 January 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Rosenfield, Kat (23 September 2018). "David Bowie's 'Space Oddity' Was The Perfect Soundtrack Song". MTV News. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Bahrampour, Tara. "David Bowie dies at 69; mesmerizing performer and restless innovator". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ Buckley 1999, pp. 49–50.

- ^ David, Bowie (31 August 2010). "Space Oddity". Musicnotes.com. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "The 15th Ivor Novello Awards". The Ivors. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ Promoted as RCA Maximillion Series, 3 Tracks For The Price of 2 (RCA 2593). The tracks were "Space Oddity", "Changes" and "Velvet Goldmine" (RCA 2593).

- ^ Steffen Hung. "David Bowie – Space Oddity". lescharts.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Sandford 1997, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Sandford 1997, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Sandford 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pegg 2016, p. 334.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 636–638.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Doggett 2012, p. 60.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pegg 2016, p. 255.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 59.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, p. 116.

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Spitz 2009, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Spitz 2009, p. 104.

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 145, 147.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, pp. 98, 104.

- ^ O'Leary 2015, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gillman & Gillman 1987, p. 172.

- ^ Life on Two Legs – Biography by Norman Sheffield

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 153–155.

- ^ Jump up to: a b O'Leary 2015, p. 99.

- ^ "Bowie @ The Beeb". BBC World Service. BBC. 8 January 2001. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Parker, Lyndsey (10 July 2019). "The odd story of 'Space Oddity': How a 'cheap shot' 'novelty record' launched David Bowie into the stratosphere 50 years ago". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 174.

- ^ "Item Display – RPM – Library and Archives Canada". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British hit singles & albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records. pp. 319–320. ISBN 1904994105. OCLC 64098209.

- ^ Jump up to: a b O'Leary 2015, pp. 99, 107.

- ^ "A NEW CAREER IN A NEW TOWN (1977–1982) – David Bowie Latest News". DavidBowie.com. 22 July 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ "Space Oddity 50th anniversary 2 x 7" vinyl box with TV remixes". David Bowie. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Space Oddity goes gold on day of box release". David Bowie. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c O'Leary 2015, p. 98.

- ^ "Clareville Grove Demos box due". davidbowie.com. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "Out Now: David Bowie, SPYING THROUGH A KEYHOLE". Rhino Entertainment. 5 April 2019. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "The 'Mercury' Demos LP box due in June". davidbowie.com. 25 April 2019. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "David Bowie Conversation Piece 5CD box due November". davidbowie.com. 4 September 2019. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "500 Songs That Shaped Rock". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "100 Greatest Rock Songs". VH1. Archived from the original on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "The 200 Best Songs of the 1960s". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ "Rocklist.net NME Greatest Singles Lists". Rocklistmusic.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...Channel 4/HMV best music of this millennium". www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Bowie at the Beeb: The Best of the BBC Radio Sessions 68–72 – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Thornton, Anthony (1 July 2008). "David Bowie – 'Live: Santa Monica '72' review". NME. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Joe, Viglione. "Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "David Live – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Randle, Chris (29 June 2017). "David Bowie: Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles '74)". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "UNDER PRESSURE: Gail Ann Dorsey on playing bass for David Bowie". PleaseKillMe.com. 20 December 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 258.

- ^ "David Bowie And Kenny Everett's Space Oddity". Mojo. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (22 July 2019). "Watch Stunning 50th Anniversary Video For David Bowie's 'Space Oddity (2019 Mix)'". Billboard. Lynne Segall. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "Space Oddity (2019 Mix) video online at midday UK". davidbowie.com. 21 July 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "Space Oddity" (Single liner notes). David Bowie. UK: Philips Records. 1969. BF 1801/304 201 BF.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ "Space Oddity" (Single liner notes). David Bowie. Germany, Netherlands: Philips Records. 1969. 704 201 BW.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ "Space Oddity" (Single liner notes). David Bowie. US: Mercury Records. 1969. 72949.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ "Space Oddity" (Single liner notes). David Bowie. US: RCA Victor. 1973. 74-0876.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ "Space Oddity" (EP liner notes). David Bowie. UK: RCA Victor. 1975. RCA 2593.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ "Space Oddity" (40th Anniversary EP) (EP digital media notes). David Bowie. UK & US: EMI. 2009. none.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ "Space Oddity 50th anniversary 2 x 7" vinyl box with TV remixes". David Bowie. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Australian-charts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity". ARIA Top 50 Singles. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in French). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 4836." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Archívum – Slágerlisták – MAHASZ" (in Hungarian). Single (track) Top 40 lista. Magyar Hanglemezkiadók Szövetsége. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Space Oddity". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity". Top Digital Download. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Japan Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Charts.nz – David Bowie – Space Oddity". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts – David Bowie – Space Oddity". portuguesecharts.com. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ "Spanishcharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity" Canciones Top 50. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity". Singles Top 100. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Hot Rock & Alternative Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Billboard Top 100 – 1973". billboardtop100of.com. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Hot Rock Songs – Year-End 2016". Billboard. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Top AFP - Audiogest - Top 3000 Singles + EPs Digitais" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Associação Fonográfica Portuguesa. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "Italian single certifications – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 31 January 2015. Select "2015" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Select "Space Oddity" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Singoli" under "Sezione".

- ^ "British single certifications – David Bowie – Space Oddity". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Knapp, Alex (13 May 2013). "Astronaut Chris Hadfield Sings David Bowie As He Departs The International Space Station". Forbes. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Davis, Lauren (12 May 2013). "Chris Hadfield sings "Space Oddity" in the first music video in space". Gawker Media. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pegg 2016, p. 260.

- ^ "Space Oddity". YouTube. 12 May 2013. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "David Bowie Official on Twitter: "CHRIS HADFIELD SINGS SPACE ODDITY IN SPACE! "Hallo Spaceboy..." Commander Chris Hadfield, currently on..."". Twitter. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie – Timeline". Facebook. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Andrew Griffin. "David Bowie: How Chris Hadfield's 'Space Oddity' cover from orbit was helped by the 'Starman'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Fleishman, Glenn (22 May 2013). "How does copyright work in space?". The Economist. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Apology to David Bowie". Ottawa Citizen. 20 June 2014. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "Bowie's last day – we had permission for a year, so our Space Oddity video comes down today. One last look". Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Space Oddity". chrishadfield.ca. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

Sources[]

- Buckley, David (1999). Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-1-85227-784-0.

- Buckley, David (2005) [First published 1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5.

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Croyden, Surrey: Adelita. ISBN 978-0-95520-177-6.

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.

- Gillman, Peter; Gillman, Leni (1987) [1986]. Alias David Bowie. New English Library. ISBN 978-0-450-41346-9.

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80854-4.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31603-225-4.

External links[]

- 1969 singles

- 1973 singles

- 1975 singles

- David Bowie songs

- Number-one singles in France

- UK Singles Chart number-one singles

- Songs about spaceflight

- Songs about fictional male characters

- Songs written by David Bowie

- Song recordings produced by Gus Dudgeon

- 1969 songs

- Philips Records singles

- Mercury Records singles

- RCA Records singles

- Major Tom

- Songs composed in C major