Special Bulletin

| Special Bulletin | |

|---|---|

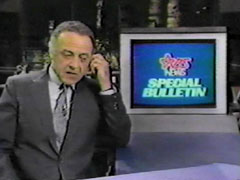

Ed Flanders as RBS anchor John Woodley. | |

| Genre | Drama Docufiction |

| Written by | Marshall Herskovitz (teleplay) Edward Zwick Marshall Herskovitz (story) |

| Directed by | Edward Zwick |

| Starring | Ed Flanders Kathryn Walker |

| Theme music composer | Ferdinand Jay Smith (promo and news music only) |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| Production | |

| Executive producer | Don Ohlmeyer |

| Producers | Marshall Herskovitz Edward Zwick (associate producer) |

| Editor | |

| Running time | 105 minutes |

| Production company | Ohlmeyer Communications Company |

| Distributor | NBC |

| Release | |

| Original network | NBC |

| Original release | March 20, 1983 |

Special Bulletin is a 1983 American made-for-television film. It was an early collaboration between director Edward Zwick and writer Marshall Herskovitz, a team that would later produce such series as thirtysomething and My So-Called Life. The movie was first broadcast March 20, 1983 on NBC as an edition of NBC Sunday Night at the Movies.[1][2]

In this movie, a terrorist group brings a homemade atomic bomb aboard a tugboat in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina in order to blackmail the U.S. Government into disabling its nuclear weapons, and the incident is caught live on television. The movie simulates a series of live news broadcasts on the fictional RBS Network.[1][2]

Synopsis[]

The entirety of the film is portrayed through the perspective of a news broadcast through the fictional RBS news network.

In Charleston, South Carolina, a skirmish is fought between Coast Guard personnel and a group of terrorists aboard a docked tugboat in Charleston Harbor. Caught in the battle, RBS reporter Steve Levitt as well as his cameraman are taken hostage aboard the boat. As part of a deal to release the surrendered coast guards, the terrorists; notably Doctors Bruce Lyman and David McKeeson ask to broadcast their demands to the U.S. Government. Dr. Lyman demands that the triggers for every nuclear device in the local area (Charleston Naval Shipyard being an important staging ground for US nuclear submarines) delivered to them. Dr. Lyman states that failure to oblige to the demand or any deviation from such plan will result in the group detonating their own improvised nuclear device stowed aboard the ship.

Subsequent investigations into Dr. Lyman and McKeeson reveal their background in nuclear weaponry and technology. Dr. Lyman himself being instrumental in the construction of the neutron bomb and Dr. McKeeson being the one who built the bomb aboard the ship, and also states that he has fitted several fail-safes and anti-tamper devices to the bomb, suggesting that he alone can disarm it. Eventually, the Department of Defense agrees to the terrorist demands and a van arrives outside the tugboat, supposedly carrying the nuclear triggers.

Moments before the handover, a power failure occurs in Charleston - all televisions including one on the tugboat go off the air. This however proves to be deliberate as a Delta Force commando team storms the boat, killing several of the terrorists including Dr. Lyman. Dr. McKeeson is cornered, but commits suicide. Steve Levitt and his cameraman are safely taken off the ship, but continue to broadcast on the dock whilst a NEST Team boards the boat to disarm the device. A camera aboard the boat records the team working, who accidentally trigger one of McKeeson's safeguards. As the team frantically try to stabilize the device, the feed is suddenly interrupted by static, at which point the broadcast returns to the RBS Studio. The hosts are clearly shaken by what they have just witnessed. The broadcast shifts to another reporter, Meg Barclay, who was aboard USS Yorktown (CV-10) 2 miles away. Footage reveals that the device exploded, resulting in a 23-kiloton nuclear blast that has caused a firestorm, destroying the city of Charleston.

Three days later, RBS broadcasts the aftermath of the detonation. Thanks to an earlier ordered evacuation, only 2000 citizens perished in the detonation. However, thousands more have been left homeless and the surrounding area will be uninhabitable for decades to come. The film ends as the news station reports on other stories across the world.

Cast[]

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Ed Flanders | John Woodley (RBS Anchor) |

| Kathryn Walker | Susan Myles (RBS Anchor) |

| Christopher Allport | Steven Levitt (WPIV reporter) |

| David Clennon | Dr. Bruce Lyman (Terrorist) |

| Rosalind Cash | Frieda Barton (Terrorist) |

| Roxanne Hart | Megan "Meg" Barclay (RBS Reporter) |

| David Rasche | Dr. David McKeeson (Terrorist) |

| Lane Smith | Morton Sanders (RBS Reporter) |

| Ebbe Roe Smith | Jim Seaver (Terrorist) |

| Roberta Maxwell | Diane Silverman (Terrorist) |

| J. Wesley Huston | Bernard Frost (WPIV) |

| William A. Gamble, Jr. | Special Forces Commander |

Impact[]

Several factors enhanced Special Bulletin's resemblance to an actual live news broadcast. The movie was shot on videotape rather than film, which gave the presentation the visual appearance of being "live". Other small touches, such as actors hesitating or stumbling over dialogue (as if being spoken extemporaneously) and small technical glitches (as would often be experienced in a live broadcast), contributed to the realism. With the exception of RBS network and news jingles, there is also no musical score used. The end credits are accompanied by the sound of a teletype.[1][2]

In addition, some specific references made the movie especially realistic to residents of Charleston. The call letters of the fictional Charleston RBS affiliate, WPIV, were close to those of NBC's then-affiliate in Charleston, WCIV. Also, a key plot element mentions "a power failure at a transmitter in North Charleston"; the TV transmitter sites are actually in Awendaw.[1][2]

The filmmakers were required to include on-screen disclaimers at the beginning and end of every commercial break in order to assure viewers that the events were a dramatization. The word "dramatization" also appeared on the screen during key moments of the original broadcast. Additionally, WCIV placed the word "Fiction" on screen at all times during its showing of the movie. The film also made use of "accelerated time"—events said to take place hours apart instead are shown only minutes apart. Nonetheless, there were still news reports of isolated panic in Charleston. Much as with the famous 1938 radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds, it was entirely possible for viewers to tune in between disclaimers and make a snap judgment about what they were seeing, although in both cases a quick flip of the dial would reveal that no other stations were covering this supposedly major news event. When the program was rebroadcast in 1984, the only disclaimers were made at the commercial breaks; there were none on the screen while the action was taking place.[3][4]

Reaction[]

Special Bulletin was nominated for six Emmy awards and won four, including Outstanding Drama Special. It also won Directors Guild of America and Writers Guild of America prizes for Zwick and Herskovitz, as well as the Humanitas Prize, which irked former NBC president Reuven Frank. In his book on TV news, Out of Thin Air, Frank called Special Bulletin "junk" and claimed he wanted to return his own Humanitas Prize in protest, "but I couldn't find it."[5][6]

Leonard Maltin's Movie and Video Guide rated Special Bulletin "way above average."[7]

The Washington Post described it as “A shrewd, keen, wise, hip, occasionally lacerating and sometimes gravely funny dark parody of network TV news coverage.” Also, “At times, the unfolding story in Special Bulletin comes across as ludicrous, but then one has to think, how much more ludicrous is it than some of the actual news events of the past 15 years or so, and the way television has honed its way of covering them? It’s a process that deserves scrutiny not just in poker-faced journals and ivory tower think tanks but on television. Praiseworthy trailblazers like the ABC News late night Viewpoint broadcasts have done this one way. Special Bulletin does it in another way-not a better one, perhaps, but in one more accessible to greater numbers of viewers.”[2]

The New York Times stated that 2,200 calls from alarmed viewers were received in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Washington and Cleveland. The WNBC-TV station in New York received 731 calls, 44 of them critical, and 43 asking if the program was real. The station manager of WCIV-TV in Charleston, Celia Shaw, said, “In retrospect, maybe it would have been better with a theoretical city, rather than Charleston, with its large number of military installations.”[8]

Home video[]

Lorimar Home Video issued Special Bulletin on VHS and Betamax, and Warner Home Video would later reissue it; these releases omit the on-screen "dramatization" overlay. Starting in January 2010, Warner Bros. made the film available on DVD for one year as part of its Warner Archive Collection. Warner's rights have since reverted to the production company and the DVD is currently out of print.[9]

See also[]

- Countdown to Looking Glass, a 1984 Canadian TV movie that used simulated news broadcasts to chronicle a Cold War showdown between the United States and the Soviet Union.

- Without Warning, an apocalyptic 1994 TV movie also presented as a faux news broadcast.

- The Day After, a 1983 made-for-TV movie about a nuclear war and its effects on the Midwest US.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rogers, Chris (September 11, 2012). "Thousand Words: "We interrupt this programme…" Reality television: Special Bulletin (Edward Zwick, 1983)". The Big Picture.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Shales, Tom (March 20, 1983). "Bulletin! The Show That Shook NBC". The Washington Post.

- ^ Stracener, William (April 30, 1984). "The repeat showing of the television movie "Special Bulletin"". United Press International.

- ^ El-Miskin, Tijani (March 1989). "Special Bulletin-Transfictional disavowal". Jump Cut. 34: 72–76.

- ^ "Special Bulletin-Awards & Nominations". Emmys-Television Academy. 2020.

- ^ Frank, Reuven, 1920-2006. (1991). Out of thin air : the brief wonderful life of network news. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-67758-6. OCLC 23461999.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Klein, Andy (November 5, 1998). "Final Jeopardy". Miami New Times.

- ^ Bedell, Sally (March 22, 1983). "NBC Nuclear-Terror Show Criticized". The New York Times.

- ^ "Widescreen Wonders." Warner Archive Podcast, 12-9-14

External links[]

- 1983 films

- 1983 drama films

- 1983 television films

- American films

- American docufiction films

- American drama films

- Cold War films

- English-language films

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- Films about terrorism in the United States

- Films directed by Edward Zwick

- Films set in Charleston, South Carolina

- NBC network original films

- Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Made for Television Movie winners