Star Control

| Star Control | |

|---|---|

Sega Genesis cover art by Boris Vallejo | |

| Developer(s) | Toys for Bob |

| Publisher(s) | Accolade |

| Producer(s) | Pam Levins |

| Designer(s) | Fred Ford Paul Reiche III |

| Programmer(s) | Fred Ford Robert Leyland |

| Artist(s) | Greg Johnson Paul Reiche III |

| Composer(s) | Kyle Freeman Tommy V. Dunbar |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, MS-DOS, Sega Mega Drive/Genesis, Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum |

| Release | July 1990 (Amiga, DOS) 1991 (ports) |

| Genre(s) | Action, strategy |

| Mode(s) | Single player, multiplayer |

Star Control: Famous Battles of the Ur-Quan Conflict, Volume IV or just simply Star Control is a science fiction video game developed by Toys for Bob and published by Accolade in 1990. It was originally released for Amiga and MS-DOS in 1990, followed by ports for the Sega Mega Drive/Genesis, Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum in 1991. The game was a commercial and critical success, and is remembered as one of the best games of all time, as well its foundation for the highly praised sequel. Two sequels were released, Star Control II in 1992 (and the free open-source remake The Ur-Quan Masters in 2002), and Star Control 3 in 1996.

Gameplay[]

Star Control is a combination of a strategy game and real-time one-on-one ship combat game. The ship combat is based on the classic game Spacewar!, while the turn-based strategy is inspired by Paul Reiche III's 1983 game Archon.[1] Players have the option to play the full game with the turn-based campaign, or to practice the one-on-one ship battles.[2]

The full game allows players to select one of 15 different scenarios, with opposing fleets arranged on a rotating star map. The player has up to three ship actions per turn, which are used to explore new stars and colonize or fortify worlds.[3] These colonies provide resources to the player's ships, such as currency and crew.[1] The goal is to move your ships across the galaxy, claim planets along the way, and finally destroy your opponent’s star base.[3]

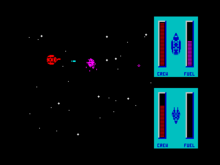

When two rival ships meet on the battlefield, an arcade-style combat sequence begins.[3] The game offers different ships to pilot, which are deliberately imbalanced in ability. Match-ups between these ships have a major influence over combat.[1] There are 14 different ships, with unique abilities for each.[3] Ships typically have a unique firing attack, as well as some kind of secondary ability. Both actions consume the ship's battery, which recharges automatically (with few exceptions). Ships have a limited amount of crew, representing the total damage a ship can take before being destroyed.[1] This ties into the strategic meta-game between combat, where the crew can be replenished at colonies.[1]

During combat, the screen frames the action between the two ships with an overhead view, zooming in as they approach each other. Players try to outgun and outmaneuver each other. There is a planet in the middle of the battlefield, providing a centre of gravity, which players can either crash into, or glide nearby to gain momentum.[1]

The story framing the gameplay is minimal compared to the sequel, described mostly in the game's scenario introductions. Some background can be found in the manuals about two warring factions. The game can be played by one player against the computer, or two players head to head.[1] As was typical of copy protection at the time, Star Control requested a special pass phrase that players found by using a three-ply code wheel, called "Professor Zorq's Instant Etiquette Analyzer".[4]

Development[]

Concept and origins[]

Star Control is the first collaboration between Paul Reiche III and Fred Ford.[5][6] Reiche had started his career working for Dungeons & Dragons publisher TSR, before developing PC games for Free Fall Associates.[7] After releasing World Tour Golf, Reiche created an advertising mock-up for what would become Star Control, showing a dreadnaught and some ships fighting. He pitched the game to Electronic Arts, before instead securing an agreement with Accolade as a publisher, thanks to Reiche's former producer taking a job there.[8] Meanwhile, Ford had started his career creating games for Japanese personal computers before transitioning to more corporate software development.[6] After a few years working at graphics companies in Silicon Valley, Ford realized he missed working in the game industry.[8] At this point, Reiche needed a programmer-engineer and Ford was seeking a designer-artist, so their mutual friends set up a gaming night to re-introduce them.[7] The meeting was hosted at game designer Greg Johnson's house,[8] and one of the friends who encouraged the meeting was fantasy artist Erol Otus.[9]

Originally called Starcon, the game began as an evolution on concepts that Reiche first created in Archon: The Light and the Dark, as well as Mail Order Monsters.[6] The vision for the game was science-fiction Archon, where asymmetric combatants fight using different abilities in space.[7] According to Ford, "StarCon is really just Archon with an S-T in front of it", pointing to the one-on-one combat and strategic modes of both games.[8] Star Control would base its combat sequences on the classic game Spacewar!,[5] as well as the core experience of space combat game Star Raiders.[10] As Ford and Reiche were still building their workflow as a team, the game took on a more limited scope compared to the sequel.[7]

Design and production[]

Fred Ford's first prototype was a two-player action game where the VUX and Yehat ships blow up asteroids, which led them to build the entire universe around that simple play experience.[6] Ford designed the Yehat ship with a crescent-shape, and the ship's shield-generator led them to optimize the ship for close combat.[8] They built on these two original ships with many additional ships and character concepts,[5] and play-tested them with friends such as Greg Johnson and Robert Leyland.[8] The team preferred to iterate on ship designs rather than plan them, as they discovered different play-styles during testing.[8] The asymmetry between the combatants became essential to the experience. Ford explained: "Our ships weren't balanced at all, one on one... but the idea was, your fleet of ships, your selection of ships in total was as strong as someone else's, and then, it came down to which matchup did you find".[11] Still, the ships were still given some balance by having their energy recharge at different rates.[8]

Although the story does not factor heavily into the game,[1] the character concepts were created based on the ship designs.[7] The team would begin with paper illustrations, followed by logical abilities for those ships, and a character concept that suited the ship's look-and-feel.[6] The first ship sketches were based on popular science fiction, such as SpaceWars! or Battlestar Galactica, and slowly evolved into original designs as they discussed why the ships were fighting each other.[8] Paul Reiche III describes their character creation process: "I know it probably sounds weird, but when I design a game like this, I make drawings of the characters and stare at them. I hold little conversations with them. 'What do you guys do?' And they tell me".[5] By the end of this process, they wrote a short summary for each alien, describing their story and personality.[8]

After creating a large ship that launches fighters on command, Reiche and Ford decided this would be a dominating race.[11] These antagonists would be called the Ur-Quan, with a motivation to dominate the galaxy to hunt for slaves, and an appearance based on a National Geographic image of a predatory caterpillar dangling over its prey.[5] They decided to organize the characters into nominally "good" and "bad" factions, each with seven unique races and ships, with the humans on the good side.[8] As they were creating the alien characters based on the ship abilities, the Spathi's cowardly personality was inspired by their backwards-shooting missiles.[7] A more robotic ship inspired an alien race called the Androsynth, whose appearance was imagined as Devo flying a spaceship.[6] The team also decided that the game would need more humanoid characters, and created the Syreen as a powerful and attractive humanoid female race.[8] Reiche and Ford were also inspired by character concepts in David Brin's The Uplift War. The designers asked what kind of race would be uplifted by the fiercely heroic Yehat, and decided to create the Shofixti as a ferocious super rodent.[7]

Each alien race also had a short victory theme song, composed by Reiche's friend Tommy Dunbar of The Rubinoos. The longer Ur-Quan theme played at the end of the game was composed by fantasy artist Erol Otus.[8]

Porting and compatibility[]

The number of visible colors was a major technological limitation at the time, and the team created different settings for CGA, EGA, and VGA monitors.[7] A separate team ported a stripped down version of the game to the Commodore 64, Spectrum and Amstrad, which meant reducing the number of ships to 8, not to mention the introduction of new bugs and balance issues.[2] Additional problems were caused by the number of simultaneous key-presses required for a multiplayer game, which required Ford to code a solution that would work across multiple different computer keyboards.[7]

Star Control was ultimately ported to the Sega Genesis,[12] in a team led by Fred Ford.[8] Because the Genesis port was a cartridge-based game with no battery backup, it lacked the scenario-creator of its PC cousin, but it came pre-loaded with a few additional scenarios not originally in the game.[13] Where the PC version featured synthesized audio, the team discovered the digital MOD file format to help port the music to console, which would later become the core music format for the sequel.[7] It took nearly 5 months to convert the code and color palates,[13] leaving little time to optimize the game under Accolade's tight schedule, leading to slowdown issues.[14][15] Released under Accolade's new "Ballistic" label for high quality games, the game was touted as the first 12-megabit cartridge created for the system.[12] The box art for the Sega version was adapted from the original PC version, this time re-painted by famed artist Boris Vallejo.[2]

The Genesis port was not authorized by Sega, which led to a lawsuit between Accolade and Sega of America.[7] Sega v. Accolade became an important legal case, creating a precedent to allow reverse engineering under fair use.[16][17] This led Sega to settle the lawsuit in Accolade's favor, making them a licensed Sega developer.[18]

Reception[]

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| CGW | |

| CVG | 68% (Amiga)[24] 90% (Sega)[25] |

| MegaTech | 90% (Sega)[19] |

| Sega16 | 8/10 (Sega)[12] |

| Videogame & Computer World | 8/10 (PC/C64)[20][21] 9/10 (Amiga)[22] |

| Entertainment Weekly | B (Sega)[26] |

| Joystick | 75% (Sega)[27] |

| The Games Machine | 88% (PC)[28] |

| Raze Magazine | 70/100 (Sega)[29] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Computer and Video Games[25] | CVG Hit |

| MegaTech[19] | Hyper Game Award |

| VG&CE[30] | Best Computer Science Fiction Game 1990 |

Star Control was a commercial success at the time, reaching the top 5 on the sales charts by September 1990.[7] According to a retrospective by Finnish gaming magazine Pelit, the game would go on to sell 120,000 copies, leading Accolade to request a sequel from creators Reiche and Ford.[31]

Critics also praised Star Control for its arcade combat, as well as its character designs, animations, and sound. MegaTech described it as "one of the best two-player Mega Drive games ever", and gave it their editorial Hyper Game Award.[19] Similarly, Computer and Video Games chose Star Control for their editorial "CVG Hit" award, citing the sound effects and the playability of the game's two-player mode.[25] The two-player mode earned additional praise from Digital Press, who also highlighted the game's artistic detail and lore.[32] Strategy Plus similarly praised the humor and personality of the aliens, and declared the graphics as "truly spectacular in 256 color VGA".[33] Italian publication The Games Machine rated the game 88%, describing it as a modern re-invention of Spacewar! with many entertaining artistic details.[28] Similarly, Videogame & Computer World praised the game's unique animations and replayable arcade mode, giving a rating of 8/10 on the PC,[20] 8/10 on the Commodore 64,[21] and 9/10 on the Amiga.[22] Entertainment Weekly praised the game for evolving the Spacewar! formula with a variety of unique ships.[26]

Some reviews were more mixed. Computer Gaming World criticized Star Control for its thin strategic gameplay, but still praised the game's arcade combat.[23] Advanced Computer Entertainment called the Amiga version "disappointing", criticizing the load times and "tacky two-dimensional combat sequences that look as if they've been borrowed from an early Eighties coin-op".[34] Computer and Video Games similarly compared Star Control to the "aging co-op Spacewars!", rating the game at 68%.[24] Raze Magazine rated the Sega version at 70/100 for lacking the polish of the PC version.[29] Joystick rated the game 75%, with strongest praise for the game's sound design.[27]

At the end of the year, Video Games & Computer Entertainment gave Star Control an award for "Best Computer Science Fiction Game", noting that "the two creators have put together a game that is great either as a full simulation or an action-combat contest".[30] They later highlighted the game in a list of science fiction releases, proclaiming "Reiche and Ford's action-strategy tour de force is one of the most absorbing and challenging science fiction games of all-time".[35] Star Control was also highlighted by Strategy Plus in their review of 1990, praising the game among other strategy titles for its unique humor.[36] The game was additionally nominated for Best Action/Arcade Program at the 1991 Spring Symposium of the Software Publishers Association.[37]

Legacy and impact[]

Star Control has earned a legacy for combining different kinds of gameplay into an artistically detailed space setting. Years after its release, Retro Gamer described Star Control as "a textbook example of good game design", where "two genres were brilliantly combined, making for a finely balanced and well-rounded game experience".[2] Sega-16 also called the game "superb in its simplicity", noting that "Star Control graphically does borrow from existing concepts, the design and presentation is so impeccably done that it stands well on its own".[12]

In 1996, Video Games & Computer Entertainment ranked it as the 127th best game of all time, describing it as "Space War enters the 90s with a touch of humor".[38] In 2001, PC Gameplay ranked Star Control as the 45th most influential game of all time, based on a survey of dozens of game studios.[39] In 2017, Polygon mentioned it in their top 500 games of all time, with its flexibility "as a melee or strategic game, it helped define the idea that games can be malleable and dynamic and players can make an experience wholly their own".[40] The game is also celebrated for the debut of the Ur-Quan, as "one of the all-time villainous races in the history of computer games".[5]

The legacy of the original Star Control is also its foundation for future games, including the critically acclaimed sequel Star Control II.[41] Retro Gamer highlighted the numerous "elements that gave Star Control 'soul'", describing it as "the seed from which the vastly expanded narrative found in Star Control 2 grew".[2] Sega-16 explains that "Star Control remains a fantastic game and a blueprint for what many would call one of if not the best game ever, Star Control II".[12] Founder of BioWare, Ray Muzyka, cites the Star Control series as an inspiration for the Mass Effect series of games, stating that "the uncharted worlds in Mass Effect comes from imagining what a freely explorable universe would be like inside a very realistic next-gen game".[42] Former BioWare writer Mike Laidlaw also praised the creativity of the Star Control ship designs, and credited the game with laying the foundation for a sequel, which influenced him as a writer on Mass Effect.[43]

Sequels and open-source remake[]

Star Control II[]

Star Control II is an action-adventure science fiction game, set in an open universe.[44] The game was originally published by Accolade in 1992 for MS-DOS, and was later ported to the 3DO with an enhanced multimedia presentation.[45] Created by Fred Ford and Paul Reiche III, it vastly expands on the story and characters introduced in the first game.[43] When the player discovers that Earth has been encased in a slave shield, they must recruit allies to liberate the galaxy.[46] The game features ship-to-ship combat based on the original Star Control, but removes the first game's strategy elements to focus on story and dialog, as seen in other adventure games.[45] Star Control II has earned acclaim as one of the best games of all time through the 1990s,[47] 2000s,[48] and 2010s.[49] It is also ranked among the best games in several creative areas, including writing,[50] world design,[51] character design,[52] and music.[53]

Star Control 3[]

Star Control 3 is an adventure science fiction video game developed by Legend Entertainment, and published by Accolade in 1996.[54][55] The story takes place after the events of Star Control II when the player must travel deeper into the galaxy to investigate the mysterious collapse of hyperspace.[56] Several game systems from Star Control II are changed.[54] Hyperspace navigation is replaced with instant fast travel, and planet landing is replaced with a colony system inspired by the original Star Control game.[55] Accolade hired Legend Entertainment to develop the game after original creators Paul Reiche III and Fred Ford decided to pursue other projects.[57] Though the game was considered a critical and commercial success upon release, it would receive unfavourable comparisons to the award-winning Star Control II.[58][59]

Cancelled Star Control 4[]

In the late 1990s, Accolade was developing Star Control 4.[60] Also known as StarCon, it was designed as a 3D space combat game.[61] By this time, Electronic Arts had agreed to become the distributor for all games developed by Accolade.[62] Accolade producer George MacDonald announced that "we want to move away from the adventure element and concentrate on what it seems the players really want – action!"[63] Though heavier on combat than previous titles, players would still have the opportunity to fly to planets and communicate with different aliens.[64] The team also created a Star Control History Compendium, to help them resolve storylines from the previous games.[63] In a playable alpha version of the game, players could control a fleet carrier, with the ability to launch a fighter that could be controlled by either the same player or a second player.[65] The game was later announced for the Sony PlayStation with plans for release in 1999, featuring a 40-hour variable storyline, and both competitive and co-operative multiplayer.[60] Electronic Arts and Accolade promoted the choice of playing as "one of two alliances (Hyperium or Crux)", with the option of operating a fighter, carrier, or turrets.[66] Another publication described the ability to select from three different alien races, with different missions that impact the storyline, and the ability to destroy entire planets.[67]

Development on the game was halted at the end of 1998. Not happy with the game's progress, Accolade put the project on hold with intentions to re-evaluate their plans for the Star Control license.[68][69] In 1999, Accolade was acquired by Infogrames SA for $50 million,[70] as one of many corporate restructurings that eventually led to Infogrames merging with Atari and re-branding under a revived Atari brand.[71] Star Control 3 thus marked the last official instalment to the series.[72][73][43]

The Ur-Quan Masters[]

By the early 2000s, Accolade's copyright license for Star Control expired, triggered by a contractual clause when the games were no longer generating royalties.[74][75] As the games were no longer available in stores, Reiche and Ford wanted to keep their work in the public eye, to maintain an audience for a potential sequel.[8] Reiche and Ford still owned the copyrights in Star Control I and II, but they could not successfully purchase the Star Control trademark from Accolade, leading them to consider a new title for a potential follow-up.[76] This led them to remake Star Control II as The Ur-Quan Masters,[77] which they released in 2002 as a free download under an open source copyright license.[78] The official free release is maintained by an active fan community,[79] and prevented Star Control II from becoming abandonware.[80]

Aftermath[]

Fans continued to demand a new Star Control game well into the late 2000s.[81][82] In the early 2000s, thousands of fans signed a petition in hopes of a sequel.[83] Toys for Bob producer Alex Ness responded in April 2006 with an article on the company website, stating that "if enough of you people out there send me emails requesting that Toys For Bob do a legitimate sequel to Star Control 2, I'll be able to show them to Activision, along with a loaded handgun, and they will finally be convinced to roll the dice on this thing".[84] In the months that followed, Ness announced the petition's impact, reporting that "there did honestly seem to be some real live interest on [Activision's] part. At least on the prototype and concept-test level. This is something we may in fact get to do when we finish our current game".[85] In a 2011 interview about their next game Skylanders: Spyro's Adventure, Paul Reiche declared that they will one day make the real sequel.[86]

Intellectual property split[]

By the early 2000s, the Star Control trademark was held by Infogrames Entertainment.[77] Star Control publisher Accolade had sold their company to Infogrames in 1999,[87] who merged with Atari and re-branded under the Atari name in 2003.[88] In September 2007, Atari released an online flash game with the name "Star Control", created by independent game developer Iocaine Studios. Atari ordered the game to be delivered in just four days, which Iocaine produced in two days.[89] Also in September, Atari applied to renew the Star Control trademark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office, citing images of Iocaine's flash game to demonstrate their Declaration of Use in Commerce.[90]

Atari declared bankruptcy in 2013, and their assets were listed for auction.[91] When Stardock became the top bidder Atari's Star Control assets, Paul Reiche indicated that he still owned the copyrighted materials from the first two Star Control games, which implied that Stardock must have purchased the Star Control trademark and the copyright in any original elements of Star Control 3. Stardock confirmed this intellectual property split soon after.[92][93][94] As Stardock began developing their new Star Control game, they re-iterated that they did not acquire the copyright to the first two games, and that they would need a license from Reiche and Ford to use their content and lore.[95] Reiche and Ford echoed this understanding in their 2015 Game Developer Conference interview, stating that Stardock's game would use the Star Control trademark only.[7] After a lawsuit, the parties ultimately agreed on the same intellectual property split.[96]

Notes and references[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kalata, Kurt (September 11, 2018). "Star Control". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Szczepaniak, John (2005). "Control & Conquer" (PDF). Retro Gamer. pp. 85–87. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Weiss, Brett (21 September 2016). Classic Home Video Games, 1989-1990: A Complete Guide to Sega Genesis, Neo Geo and TurboGrafx-16 Games. McFarland. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-4766-6794-2. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Andrew (2017-03-16). History of Digital Games: Developments in Art, Design and Interaction. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-317-50380-4.

- ^ a b c d e f DeMaria, Rusel (December 7, 2018). High Score! Expanded: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games 3rd Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-429-77139-2. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Barton, Matt (April 19, 2016). Honoring the Code: Conversations with Great Game Designers. CRC Press. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-1-4665-6754-2. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Fred Ford & Paul Reiche III (June 30, 2015). "Classic Game Postmortem: Star Control". YouTube. Game Developers Conference. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hutchinson, Lee (July 7, 2020). Dacanay, Sean; Niehaus, Marcus (eds.). "Star Control Creators Paul Reiche & Fred Ford: Extended Interview". Ars Technica. Archived (Transcript) from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

(2:00-16:04)

- ^ Hutchinson, Lee (October 26, 2018). "Video: The people who helped make Star Control 2 did a ton of other stuff". Ars Technica. Archived (Transcript) from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Aycock, Heidi E H (January 1992). "Principles of Good Design - Fun Comes First". Compute. p. 94. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, Lee (October 23, 2018). "War Stories: How Star Control II Was Almost TOO Realistic". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Galway, Benjamin (August 14, 2006). "Genesis Review - Star Control". Sega 16. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Staff (May 1991). "Behind the Screens at Accolade Software". Electronic Gaming Monthly. p. 36. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "Emails from Fred Ford". IGN - Classic Gaming. May 15, 2001. Archived from the original on May 15, 2001. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Log of the 2007-06-13 IRC session with Toys for Bob: "The same goes for the Genesis version of SC1 where we did a quick port with the intention of optimizing it for speed, but they though (sic) having a 12megabit cartridge was a much better selling point".

- ^ Raja, Vinesh; Fernandes, Kiran J. (2007). Reverse Engineering: An Industrial Perspective. Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-1-84628-856-2. ISSN 1860-5168. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Sega Enterprises Ltd. v. Accolade, Inc. (977 F.2d 1510 (9th Cir. 1992)).Text

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2010). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-56087-2. OCLC 842903312. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Star Control II (Review). MegaTech Issue 19. July 1993. p. 111. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Staff (1990-11-15). Review - Star Control. Videogame & Computer World 1990-21. p. 15. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Staff (April 1991). New Releases - Star Control. Videogame & Computer World 1991-07. p. 20. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Staff (February 1991). Reviews - Star Control. Italy: Videogame & Computer World 1991 Issue 04. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Brooks, M. Evan (November 1992). "Strategy & Wargames: The Future (2000-....)". Computer Gaming World. p. 99. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ a b Staff (April 1991). Amiga Reviews - Star Control. Computer and Video Games Magazine Issue 113. p. 68.

- ^ a b c Glancey, Paul; Leadbetter, Richard (July 1991). Review - Star Control. Computer and Videogames Magazine Issue 116. pp. 108–110. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Strauss, Bob (May 24, 1991). "New Videogames - Star Control". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Staff (July 1991). Star Control (Review). France: Joystick Issue 018. p. 180. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Giorgi, Stefano (January 1991). Review - Star Control. Italy: The Games Machine Issue 27. pp. 73–74. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Star Control (Review). Raze Magazine Issue 12. October 1991. pp. 50–51. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Staff (February 1991). "VG&CE's Best Games - Best Computer Science-Fiction Game" (PDF). Video Games & Computer Entertainment. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Pelit (March 21, 2006). "Star Control - Kontrollin aikakirjat". Pelit. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Staff (November 1991). Reviews - Star Control. Digital Press - Issue 02. pp. 5–6. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Walker, Brian (November 1990). Star Control - Planet of the Japes. Strategy Plus. p. 13.

- ^ Star Control (Review). Advanced Computer Entertainment - Issue 43. April 1991. p. 67.

- ^ Katz, Arnie (April 1991). "Games Beyond Tomorrow - A Galaxy of Science Fiction Games". Video Games & Computer Entertainment. p. 86. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Walker, Brian (January 1991). 1990 - A Walkthru. Strategy Plus - Issue 4. p. 29.

- ^ Staff (June 1991). Celebrating Software - The 1991 Spring Symposium of the Software Publishers Association. Computer Gaming World - Issue 83. pp. 64–67.

- ^ "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. pp. 64–80. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ "The Big 50 Most Influential Games Of All Time!". PC Gameplay. April 4, 2001. Archived from the original on April 4, 2001. Retrieved 2021-10-03.

- ^ Polygon Staff (November 29, 2017). "500 Best Games of All Time". Polygon. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ IGN PC Team (December 3, 2008), The Wednesday 10: Franchises We Want Resurrected, IGN, retrieved October 20, 2020

- ^ John Gaudiosi (November 11, 2007). "Critically Acclaimed Mass Effect Powered by Unreal Engine 3". Unrealengine.com. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Sanchay, Pre (May 12, 2021). Kalata, Kurt (ed.). "Now and Forever: The Legacy of the Star Control II Universe – Hardcore Gaming 101". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Hamilton, Kirk (September 19, 2013). "The Game That "Won" Our Classic PC Games List (If It Had A Winner)". Kotaku. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Kalata, Kurt (September 11, 2018). "Star Control II". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ Cobbett, Richard (September 10, 2015). "Have You Played... Star Control 2?". Rock Paper Shotgun. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^

- "PC Gamer Top 40: The Best Games of All Time". PC Gamer US. No. 3. August 1994. pp. 32–42.

- "The PC Gamer Top 50 PC Games of All Time". PC Gamer. No. 5. April 1994. pp. 43–56.

- "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. pp. 64–80. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- "The Fifty Best Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 50. February 1999.

- ^

- Buecheler, Chris "shaithis" (September 2000). "The Gamespy Hall of Fame – Star Control 2". GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 30, 2001. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Kasavin, Greg (June 27, 2003). "The Greatest Games of All Time – Star Control 2". GameSpot. Archived from the original on August 14, 2005. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games of All Time (2003)". IGN. November 23, 2005. Archived from the original on November 23, 2005. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games (2005)". IGN. August 2, 2005. Archived from the original on August 2, 2005. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^

- "The 100 best PC games of all time". PC Gamer. February 19, 2011. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "HG101 Presents: The 200 Best Video Games of All Time". Hardcore Gaming 101. December 5, 2015. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Hamilton, Kirk (September 19, 2013). "The Game That 'Won' Our Classic PC Games List (If It Had A Winner)". Kotaku. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^

- "GameSpot's Best 10 Endings". GameSpot. March 2, 2000. Archived from the original on March 2, 2000. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "GameSpot's Ten Best Endings: RC". GameSpot. March 1, 2000. Archived from the original on March 1, 2000. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^

- Patrick Lindsey (January 7, 2015). "8 Games That Capture the Infinite Potential of Space". Paste magazine.

- "GameSpot's Top 10 Gameworlds". GameSpot. October 18, 2000. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Jeff Drake (November 10, 2019). "The 10 Biggest Open World Games". Game Rant. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Stuart Houghton (May 2, 2017). "10 classic game worlds we'd love to revisit". Red Bull. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^

- "The Ten Best Computer Game Villains - The Ur Quan". GameSpot. October 13, 1999. Archived from the original on October 13, 1999. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "Reader's Choice: Best Villains - Villains 5-1". GameSpot. October 12, 1999. Archived from the original on October 12, 1999. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^

- Brad Stabler, John Twells, Miles Bowe, Scott Wilson and Tom Lea (April 18, 2015). "The 100 best video game soundtracks of all time". FACT. Retrieved August 6, 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "The Ten Best Game Soundtracks". GameSpot. October 13, 1999. Archived from the original on October 13, 1999. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "The Ten Best Game Soundtracks: RC". GameSpot. September 1, 1999. Archived from the original on October 12, 1999. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ a b "New Release: Star Control 3". GOG.com. September 15, 2011. Archived from the original on November 23, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Kalata, Kurt (September 11, 2018). "Star Control 3". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt (September 11, 2018). "Star Control 3". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ Barton, Matt (April 19, 2016). Honoring the Code: Conversations with Great Game Designers. CRC Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-4665-6754-2. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt (September 11, 2018). "Star Control 3". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "Star Control III". GOG.com. September 14, 2011. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Star Control 4. PLAY Issue 039. October 1998. p. 81. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Pro News - Star People. Playstation Pro Issue 24. September 1998. p. 11. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "Electronic Arts signs Accolade". Silicon Valley Business Journal. March 24, 1996. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ a b StarCon. PC Gamer - Volume 5 Issue 1. January 1998. p. 46.

- ^ StarCon (Preview). Italy: PSM (PlayStation Magazine) 005. August 1998. p. 47. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "Next-Generation Online: StarCon Preview". Next-Generation Online. August 5, 1998. Archived from the original on December 3, 1998. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Pro-Prospects - StarCon. Playstation Pro Issue 26. November 1998. p. 82. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Star Control 4 (Preview). Playstation Plus Issue 37. October 1998. p. 37. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ PlayStation Gaming News - StarCon Heads Back to the Drawing Board. PSExtreme Issue 37. December 1998. p. 17.

- ^ IGN Staff (October 6, 1998), Accolade's Starcon Cancelled, IGN, retrieved October 20, 2020

- ^ "COMPANY NEWS; ACCOLADE IS BOUGHT BY INFOGRAMES ENTERTAINMENT (Published 1999)". The New York Times. April 20, 1999. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Haywald, Justin (May 29, 2009). "Atari Sheds Infogrames Branding : News from 1UP.com". 1up. Archived from the original on June 8, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Star Control III". GOG.com. September 14, 2011. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Booker, Logan (January 12, 2013). "Relive The Glory Of Star Control II In Delicious High Definition With Ur-Quan Masters HD". Kotaku AU. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Hutchison, Lee (July 7, 2020). Dacanay, Sean; Niehaus, Marcus (eds.). "Star Control Creators Paul Reiche & Fred Ford: Extended Interview". Ars Technica. Archived (Transcript) from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

Fred Ford: Star Control II, well and Star Control I have always been near and dear to our hearts. It's the first things we worked on, the first things we poured our passion in together. We have some diehard fans as a result of those two games and we wanted to service them and lay the groundwork for a return and keep the games in the fronts of their minds as much as possible so that when we were finally able to return to it we would still have a living audience.

Paul Reiche: There was a confluence of events that helped this. One was Accolade stopped selling the game and we stopped earning royalties right around your 2000 and that triggered the termination of their exclusive right to sell our game. So we got our game back. What we didn't have was the name Star Control. That was a trademark that the publisher owned and we negotiated back and forth with them, but ultimately we weren't able to come to terms for the name. So we decided, well we can't use that name, let's give it a new name, so we used the Ur-Quan Masters ... So the "Ur-Quan Masters" project, the open-source release of the game we created as Star Control II, that really kept our game alive in the doldrums between say 2001 or 2002 and then 2011 when our games began to be sold again through Good Old Games, known as GOG, which is an electronic distributor of classic games. - ^ "Interview with Fred Ford". classicgaming.com. May 15, 2001. Archived from the original on May 15, 2001. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

Fred Ford: [Accolade] owe us another payment for our portion of the property. They have told us they are going to default on this payment which means we are back to owning the characters and settings. They still own the trademark/name and continue to look for someone to buy it from them.

- ^ Pelit (March 21, 2006). "Star Control - Kontrollin aikakirjat". Pelit. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Trey Walker (2002-06-26). "Star Control II remake in the works". GameSpot.

- ^ Wen, Howard (11 August 2005). "The Ur-Quan Masters". linuxdevcenter.com. O'Reilly Media. Archived from the original on 2016-03-16.

When the original developers of Star Control 2 contacted the online Star Control fan community, they presented an enticing question: if they released the source to the 3DO version of Star Control 2 under GPL, would anybody be interested in porting it to modern-day computers? Michael Martin, a 26-year-old Ph.D. student at Stanford University, answered the call. After removing proprietary 3DO-specific components from the code, the developers released the source for Star Control 2 to the public.

- ^ Meer, Alec (January 7, 2013). "Ur-Quan Masters HD: A Star Control 2 Remake". Rock Paper Shotgun. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Fox, Matt (2012-12-01). The Video Games Guide: 1,000+ Arcade, Console and Computer Games, 1962-2012, 2d ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0067-3.

- ^ Classics Reborn! Vol. 3 - IGN, retrieved 2020-11-16

- ^ The Wednesday 10: Franchises We Want Resurrected - IGN, retrieved 2020-09-08

- ^ Staff (January 2001). "Ur-Quan Masters". PC Gamer UK. No. 92. p. 31.

- ^ Sinclair, Brendan (April 14, 2006). "GameSpot's Rumor Control: Star Control sequel in the works?". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 23, 2006. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Ness, Alex (June 14, 2007). "Toys for Bob - News". toysforbob.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

Alex Ness: Star Control Sequel Update: Here comes that update. Well, we have talked to our parent company Activision about doing a Star Control sequel, quite seriously, and there did honestly seem to be some real live interest on their part. At least on the prototype and concept-test level. This is something we may in fact get to do when we finish our current game and clean our room. Again, I will continue to say that I really appreciate everybody's email and petition support. Believe me, it helps. Publishers are generally very scared to release original console games or in this case, a franchise game but the franchise is so old it might as well be original. ... So the more we show them that there is a sizeable, as well as wonderful and passionate, fan base out there, the less frightened they'll be.

- ^ "Interview: Paul Reiche Skylanders Spyro's Adventure". ComputerAndVideogames.com. October 7, 2011. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

Paul Reiche III: 22 years ago we founded Toys for Bob -- Fred Ford and myself -- making Star Control 1 and II, science fiction games which to this day have a bizarrely-dedicated fan following. And we promise someday we will make the real sequel.

Alt URL - ^ "Company News; Accolade is Bought by Infogrames Entertainment". The New York Times. April 20, 1999. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Haywald, Justin (May 29, 2009). "Atari Sheds Infogrames Branding : News from 1UP.com". 1up. Archived from the original on June 8, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Iocaine Studios Blog » Blog Archive » Life After Hyperbol". 2008-05-11. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Atari, Inc. (September 18, 2007). "Combined Declaration of Use In Commerce & Application For Renewal of Registration of A Mark Under Sections 8 & 9 - Star Control". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "World of Tanks Dev Bids on Auctioned Atari Assets | The Escapist". v1.escapistmagazine.com. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ Vazquez, Suriel. "Star Control: Origins Removed From GoG, Steam Amidst Legal Battle Between Stardock And Series Creators". Game Informer. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Open source Star Control 2 team express doubts over Atari IP sale". PC Invasion. 2013-07-23. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ "There's a new Star Control coming!". Critical Hit. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ Bradley Wardell (September 3, 2015). "Star Control: September 2015 update". Stardock. Archived from the original on 2016-08-26. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

... my position is that Stardock doesn't have the legal rights to the original lore either. Or, if we did, we have long since refuted those rights. The Star Control classic lore are the copyright of Paul Reiche and Fred Ford.

- ^ Hutchinson, Lee (2019-06-11). "Stardock and Star Control creators settle lawsuits—with mead and honey". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

External links[]

- Creators of Star Control—developer blog

- The Pages of Now and Forever—a fan site

- Star Control at MobyGames

- Star Control on classic reload

- Star Control

- 1990 video games

- Accolade (company) games

- Amiga games

- Amstrad CPC games

- Commodore 64 games

- DOS games

- Games about extraterrestrial life

- Games commercially released with DOSBox

- MacOS games

- Multidirectional shooters

- Multiplayer and single-player video games

- Sega Genesis games

- Space combat simulators

- Space opera video games

- Toys for Bob games

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games using code wheel copy protection

- ZX Spectrum games