Steal This Book

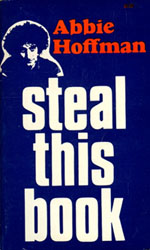

Cover of Steal This Book | |

| Author | Abbie Hoffman |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Pirate Editions / Grove Press |

Publication date | 1971 |

| Pages | 308 +xii, illustrations, bibliography[1] |

| ISBN | 1-56858-053-3 |

| OCLC | 32589277 |

| 335/.83 20 | |

| LC Class | HX843.7.H64 A3 1971a |

Steal This Book is a book written by Abbie Hoffman. Written in 1970 and published in 1971, the book exemplified the counterculture of the sixties. The book sold more than a quarter of a million copies between April and November 1971.[2]

The book is, in the style of the counterculture, mainly focused on ways to fight against the government and against corporations in any way possible. The book is written in the form of a guide to the youth. Hoffman, a political and social activist himself, used many of his own activities as the inspiration for some of his advice in Steal This Book.[3]

Creation[]

The main author of the book, Abbie Hoffman, was one of the most influential and recognizable North American activists of the late 1960s and early 1970s, gaining fame with his leadership in anti-Vietnam War protests. In the introduction, Hoffman writes that 50 people were involved in the creation of Steal This Book. Izak Haber and Bert Cohen are credited on the title page as "co-conspirator" and "accessory after the fact", respectively. Steal This Book was written in the climate of the counterculture, in which opposition to tradition and government was rampant, and experimentation with new forms of living was encouraged. When the book was published, it took hold among the new left, especially among students on college campuses, such as Brandeis University, where Hoffman had been a student.[4]

Content[]

Steal This Book is divided into three sections, "Survive!", "Fight!" and "Liberate!". There is also an introduction and appendix that lists "approved" organizations and other books worth stealing.

"Survive!" gives information and methods for obtaining goods and services for free or at discounted rates. A wide range of things are covered, including food, clothing, furniture, transportation, land, livestock, housing, education, medical care, communication, entertainment, money, and drugs. There is further advice on slug coins, panhandling, welfare, shoplifting, growing cannabis, and establishing a commune.

"Fight!" includes chapters on starting an underground press, broadcasting through guerrilla radio or guerrilla television, non-violent demonstrations and how to protect oneself if they become violent, how to make an assortment of home-made bombs, first aid for street fighters, legal advice, how to seek political asylum, guerrilla warfare, gun laws, and identification papers.

The final section, "Liberate!", contains information particular to four major cities: New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

Hoffman has an idiosyncratic writing style, and incorporates slang specific to his subculture—e.g., referring to his country as "Amerika." In the book, Hoffman calls America the "Pig Empire" and contends that it is not immoral to steal from it—in fact, Hoffman wrote, it is immoral not to do so.[5] The term was picked up by the Yippies, and was widely used by what became known as the "Woodstock Nation."[6] Some of the information in the book has since become obsolete for technological or regulatory reasons, but the book iconically reflects the hippie zeitgeist.[7]

Publication and reception[]

Steal This Book was rejected by at least 30 publishers before it was able to get into print, and Hoffman was eventually forced to make a publishing company of his own, Pirate Editions, to sell the book, with Grove Press as the distributor. Some of the publishers rejected the book out of moral opposition to its content, while others were afraid of the government. Some editors feared a negative reaction from booksellers, to the title as well as the content. This fear proved to be well-founded; in the US, many regional distributors and book stores were unwilling to carry the book. In Canada, it was banned by the government.

Once it got into print, Steal This Book had many readers and became a bestseller mainly through word of mouth. Dotson Rader in The New York Times described it as a "necessary" work "of warning and practical knowledge" that had been written with "gentleness and affection." He wrote that the book had received no reviews and that only one paper had permitted an advertisement, though the book had sold 100,000 copies. Rader felt that the "remarkable" suppression of the book constituted a form of "fearsome censorship."[8] Hoffman was quoted saying, "It's embarrassing when you try to overthrow the government and you wind up on the Best Seller's List."[9]

Subsequent to publication, two contributors to the book, Tom Forcade and Izak Haber, had a dispute with Hoffman. Forcade accused him of failing to pay sufficient royalties, contravening the contract Hoffman had made. Hoffman responded that Forcade had done an "inadequate job" of editing the book. Haber threatened to sue Hoffman for breaking his contract; he claimed that he was due 22 percent of the royalties for having compiled and written the book, but received only $1,000.[10]

See also[]

- Steal This Movie!

- Woodstock Nation (book)

- The Anarchist Cookbook

- Steal This Film

- Steal This Album!

- "Steal This Episode"

- "Download This Song" by MC Lars

References[]

- ^ CATNYP: New York Public Library online catalog

- ^ Bill Hartel (August 26, 1996). "Steal This Book-Abbie's Magnum Opus".

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. (21 Feb 2012). "The Chicago Seven Conspiracy Trial". UMKC School of Law.

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (1987). The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. Toronto: Bantam. ISBN 9780553052336. OCLC 781900043.

- ^ Raskin, Jonah (1996). For the Hell of It. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21379-3.

- ^ Harris, Randy (1993). The Linguistics Wars. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509834-X.

- ^ Lezard, Nicholas (May 25, 2002). "Direct action". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Rader, Dotson (July 18, 1971). "Book Review: Steal This Book". The New York Times. p. BR19.

- ^ Solheim, Bruce Olav (2006). The Vietnam War Era: A Personal Journey. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-275-98308-6.

- ^ Graham, Fred P. (September 9, 1971). "Abbie Hoffman Accused Before 'Court' of Peers". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

External links[]

- 1971 non-fiction books

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Literature critical of work and the work ethic

- Non-fiction books about consumerism