Streaming media

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2021) |

| E-commerce |

|---|

| Online goods and services |

|

| Retail services |

|

| Marketplace services |

|

| Mobile commerce |

|

| Customer service |

|

| E-procurement |

| Purchase-to-pay |

| Super-apps |

Streaming media is multimedia that is delivered and consumed in a continuous manner from a source, with little or no intermediate storage in network elements. Streaming refers to the delivery method of content, rather than the content itself.

Distinguishing delivery method from the media applies specifically to telecommunications networks, as most of the traditional media delivery systems are either inherently streaming (e.g. radio, television) or inherently non-streaming (e.g. books, videotape, audio CDs). There are challenges with streaming content on the Internet. For example, users whose Internet connection lacks sufficient bandwidth may experience stops, lags, or slow buffering of the content. And users lacking compatible hardware or software systems may be unable to stream certain content. With the use of buffering content just a few seconds in advance, the quality can get much better.

Livestreaming is the real-time delivery of content during production, much as live television broadcasts content via television channels. Livestreaming requires a form of source media (e.g. a video camera, an audio interface, screen capture software), an encoder to digitize the content, a media publisher, and a content delivery network to distribute and deliver the content.

Streaming is an alternative to file downloading, a process in which the end-user obtains the entire file for the content before watching or listening to it. Through streaming, an end-user can use their media player to start playing digital video or digital audio content before the entire file has been transmitted. The term "streaming media" can apply to media other than video and audio, such as live closed captioning, ticker tape, and real-time text, which are all considered "streaming text".

Streaming is most prevalent in video on demand and streaming television services. Other services stream music. Video game live streaming uses streaming for online gaming.

Etymology[]

The term "streaming" was first used for tape drives manufactured by Data Electronics Inc. that were meant to slowly ramp up and run for the entire track; slower ramp times lowered drive costs. "Streaming" was applied in the early 1990s as a better description for video on demand and later live video on IP networks. It was first done by Starlight Networks for video streaming and Real Networks for audio streaming. Such video had previously been referred to by the misnomer "store and forward video."[1]

Precursors[]

Beginning in 1881, Théâtrophone enabled subscribers to listen to opera and theatre performances over telephone lines. This operated until 1932. The concept of media streaming eventually came to America.[2]

In the early 1920s, George O. Squier was granted patents for a system for the transmission and distribution of signals over electrical lines,[3] which was the technical basis for what later became Muzak, a technology streaming continuous music to commercial customers without the use of radio.

The Telephone Music Service, a live jukebox service, began in 1929 and continued until 1997.[4][5] The clientele eventually included 120 bars and restaurants in the Pittsburgh area. A tavern customer would deposit money in the jukebox, use a telephone on top of the jukebox, and ask the operator to play a song. The operator would find the record in the studio library of more than 100,000 records, put it on a turntable, and the music would be piped over the telephone line to play in the tavern. The music media began as 78s, 33s and 45s, played on the six turntables they monitored. CDs and tapes were incorporated in later years.

The business had a succession of owners, notably Bill Purse, his daughter Helen Reutzel, and finally, Dotti White. The revenue stream of each quarter was split 60% to the music service and 40% to the tavern owner.[6] This business model eventually became unsustainable due to city permits and the cost of setting up these telephone lines.[5]

History[]

Early development[]

Attempts to display media on computers date back to the earliest days of computing in the mid-20th century. However, little progress was made for several decades, primarily due to the high cost and limited capabilities of computer hardware. From the late 1980s through the 1990s, consumer-grade personal computers became powerful enough to display various media. The primary technical issues related to streaming were having enough CPU and bus bandwidth to support the required data rates, achieving real-time computing performance required to prevent buffer underrun and enable smooth streaming of the content. However, computer networks were still limited in the mid-1990s, and audio and video media were usually delivered over non-streaming channels, such as playback from a local hard disk drive or CD-ROMs on the end user's computer.

In 1990 the first commercial Ethernet switch was introduced by Kalpana, which enabled the more powerful computer networks that led to the first streaming video solutions used by schools and corporations.

Practical streaming media was only made possible with advances in data compression, due to the impractically high bandwidth requirements of uncompressed media. Raw digital audio encoded with pulse-code modulation (PCM) requires a bandwidth of 1.4 Mbit/s for uncompressed CD audio, while raw digital video requires a bandwidth of 168 Mbit/s for SD video and over 1000 Mbit/s for FHD video.[7]

Late 1990s to early 2000s[]

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, users had increased access to computer networks, especially the Internet. During the early 2000s, users had access to increased network bandwidth, especially in the last mile. These technological improvements facilitated the streaming of audio and video content to computer users in their homes and workplaces. There was also an increasing use of standard protocols and formats, such as TCP/IP, HTTP, HTML as the Internet became increasingly commercialized, which led to an infusion of investment into the sector.

The band Severe Tire Damage was the first group to perform live on the Internet. On June 24, 1993, the band was playing a gig at Xerox PARC while elsewhere in the building, scientists were discussing new technology (the Mbone) for broadcasting on the Internet using multicasting. As proof of PARC's technology, the band's performance was broadcast and could be seen live in Australia and elsewhere. In a March 2017 interview, band member Russ Haines stated that the band had used approximately "half of the total bandwidth of the internet" to stream the performance, which was a 152 × 76 pixel video, updated eight to twelve times per second, with audio quality that was, "at best, a bad telephone connection."[8]

RealNetworks pioneered the broadcast of a baseball game between the New York Yankees and the Seattle Mariners over the Internet in 1995.[9] The first symphonic concert on the Internet—a collaboration between the Seattle Symphony and guest musicians Slash, Matt Cameron, and Barrett Martin—took place at the Paramount Theater in Seattle, Washington, on November 10, 1995.[10]

Business developments[]

The first commercial streaming product appeared in late 1992 and was named StarWorks.[11] StarWorks enabled on-demand MPEG-1 full-motion videos to be randomly accessed on corporate Ethernet networks. Starworks was from Starlight Networks, who also pioneered live video streaming on Ethernet and via Internet Protocol over satellites with Hughes Network Systems.[12] Other early companies that created streaming media technology include RealNetworks (originally known as Progressive Networks) and Protocomm both prior to widespread World Wide Web usage. Once the web became popular in the late 90s, streaming video on the internet blossomed from startups such as VDOnet (later acquired by RealNetworks) and Precept (later acquired by Cisco).

Microsoft developed a media player known as ActiveMovie in 1995 that supported streaming media and included a proprietary streaming format, which was the precursor to the streaming feature later in Windows Media Player 6.4 in 1999. In June 1999 Apple also introduced a streaming media format in its QuickTime 4 application. It was later also widely adopted on websites along with RealPlayer and Windows Media streaming formats. The competing formats on websites required each user to download the respective applications for streaming and resulted in many users having to have all three applications on their computer for general compatibility.

In 2000 Industryview.com launched its "world's largest streaming video archive" website to help businesses promote themselves.[13] Webcasting became an emerging tool for business marketing and advertising that combined the immersive nature of television with the interactivity of the Web. The ability to collect data and feedback from potential customers caused this technology to gain momentum quickly.[14]

Around 2002, the interest in a single, unified, streaming format and the widespread adoption of Adobe Flash prompted the development of a video streaming format through Flash, which was the format used in Flash-based players on video hosting sites. The first popular video streaming site, YouTube, was founded by Steve Chen, Chad Hurley and Jawed Karim in 2005. It initially used a Flash-based player, which played MPEG-4 AVC video and AAC audio, but now defaults to HTML5 video.[15] Increasing consumer demand for live streaming prompted YouTube to implement a new live streaming service to users.[16] The company currently also offers a (secured) link returning the available connection speed of the user.[17]

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) revealed through its 2015 earnings report that streaming services were responsible for 34.3 percent of the year's total music industry's revenue, growing 29 percent from the previous year and becoming the largest source of income, pulling in around $2.4 billion.[18][19] US streaming revenue grew 57 percent to $1.6 billion in the first half of 2016 and accounted for almost half of industry sales.[20]

Streaming wars[]

The term streaming wars was coined to discuss the new era of competition between video streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, HBO Max, Disney+, Apple TV+, and Peacock.[21]

Competition among online platforms has forced them to find ways to differentiate themselves. One key way they have done this is by offering exclusive content, often self-produced and created specifically for a market. This approach to streaming competition, can have disadvantages for consumers and for the industry as a whole. Once content is made available online, the corresponding piracy searches decrease. Competition or legal availability across multiple platforms effectively deters online piracy and more exclusivity does not necessarily translate into higher average investment in content, as investment decisions are also dependent on the level and type of competition in online markets.[22]

Use by the general public[]

Advances in computer networking, combined with powerful home computers and operating system advances, made streaming media practical and affordable for the public. Stand-alone Internet radio devices emerged to offer listeners a non-technical option for listening to audio streams. These audio streaming services became increasingly popular, as streaming music reached a record of 118.1 billion streams in 2013.[23]

"Streaming creates the illusion—greatly magnified by headphone use, which is another matter—that music is a utility you can turn on and off; the water metaphor is intrinsic to how it works. It dematerializes music, denies it a crucial measure of autonomy, reality, and power. It makes music seem disposable, impermanent. Hence it intensifies the ebb and flow of pop fashion, the way musical 'memes' rise up for a week or a month and are then forgotten. And it renders our experience of individual artists/groups shallower."

—Robert Christgau, 2018[24]

In 1996, Marc Scarpa produced the first large-scale, online, live broadcast, the Adam Yauch-led Tibetan Freedom Concert, an event that would define the format of social change broadcasts. Scarpa continued to pioneer in the streaming media world with projects such as Woodstock '99, Townhall with President Clinton, and more recently Covered CA's campaign "Tell a Friend Get Covered" which was live streamed on YouTube.

In general, multimedia content is data intensive, so media storage and transmission costs are still significant. Media is generally compressed for transport and storage. Increasing consumer demand for streaming of high-definition (HD) content has led the industry to develop technologies such as WirelessHD and G.hn, which are optimized for streaming HD content.

A media stream can be streamed either live or on demand. Live streams are generally provided by a means called true streaming. True streaming sends the information straight to the computer or device without saving to a local file. On-demand streaming is provided by a means called progressive streaming or progressive download. Progressive streaming saves the received information to a local file and then is played from that location. On-demand streams are often saved to files for extended amounts of time; while the live streams are only available at one time only (e.g. during the football game).[25]

Streaming media is increasingly being coupled with use of social media. For example, sites such as YouTube encourage social interaction in webcasts through features such as live chat, online surveys, user posting of comments online and more. Furthermore, streaming media is increasingly being used for social business and e-learning.[26] Many developers have introduced HD streaming apps that work on smaller devices such as tablets and smartphones for everyday purposes.

The State of Pay TV, OTT and SVOD 2017 report said that 70 percent of those viewing content did so through a streaming service, and that 40 percent of TV viewing was done this way, twice the number from five years earlier. Millennials, the report said, streamed 60 percent of content.[27]

Transition from a DVD-based to streaming culture[]

One of the movie streaming industry's largest impacts was on the DVD industry, which effectively met its demise with the mass popularization of online content. The rise of media streaming caused the downfall of many DVD rental companies such as Blockbuster. In July 2015, The New York Times published an article about Netflix's DVD services. It stated that Netflix was continuing their DVD services with 5.3 million subscribers, which was a significant drop from the previous year. On the other hand, their streaming services had 65 million members.[28]

The roots of music streaming: Napster[]

Music streaming is one of the most popular ways in which consumers interact with streaming media. In the age of digitization, the private consumption of music transformed into a public good largely due to one player in the market: Napster.

Napster, a peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing network where users could upload and download MP3 files freely, broke all music industry conventions when it launched in early 1999 in Hull, Massachusetts. The platform was developed by Shawn and John Fanning as well as Sean Parker.[29] In an interview from 2009, Shawn Fanning explained that Napster "was something that came to me as a result of seeing a sort of an unmet need and the passion people had for being able to find all this music, particularly a lot of the obscure stuff which wouldn't be something you go to a record store and purchase, so it felt like a problem worth solving."[30]

Not only did this development disrupt the music industry by making songs that previously required payment to acquire freely accessible to any Napster user, it demonstrated the power of P2P networks in turning any digital file into a public, shareable good. For the brief period of time that Napster existed, mp3 files fundamentally changed as a type of good. Songs were no longer financially excludable – barring access to a computer with internet access – and they were not rival, meaning if one person downloaded a song it did not diminish another user from doing the same. Napster, like most other providers of public goods, faced the problem of free riding. Every user benefits when an individual uploads an mp3 file, but there is no requirement or mechanism that forces all users to share their music. Thus, Napster users were incentivized to let others upload music without sharing any of their own files.

This structure revolutionized the consumer's perception of ownership over digital goods – it made music freely replicable. Napster quickly garnered millions of users, growing faster than any other business in history. At the peak of its existence, Napster boasted about 80 million users globally. The site gained so much traffic that many college campuses had to block access to Napster because it created network congestion from so many students sharing music files.[31]

The advent of Napster sparked the creation of numerous other P2P sites including LimeWire (2000), BitTorrent (2001), and the Pirate Bay (2003). The reign of P2P networks was short-lived. The first to fall was Napster in 2001. Numerous lawsuits were filed against Napster by various record labels, all of which were subsidiaries of Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group, or EMI. In addition to this, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) also filed a lawsuit against Napster on the grounds of unauthorized distribution of copyrighted material, which ultimately led Napster to shutting down in 2001.[31] In an interview with Gary Stiffelman, who represents Eminem, Aerosmith, and TLC, he explained why Napster was a problem for record labels: loss in revenue. In an interview with the New York Times, Stiffelman said, "I’m not an opponent of artists’ music being included in these services, I'm just an opponent of their revenue not being shared."[32]

The fight for intellectual property rights: A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc.[]

The lawsuit A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc. fundamentally changed the way consumers interact with music streaming. It was argued on 2 October 2000 and was decided on 12 February 2001. The Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that a P2P file sharing service could be held liable for contributory and vicarious infringement of copyright, serving as a landmark decision for Intellectual property law.[33]

The first issue that the Court addressed was "fair use," which says that otherwise infringing activities are permissible so long as it is for purposes "such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching [...] scholarship, or research."[34] Judge Beezer, the judge for this case, noted that Napster claimed that its services fit "three specific alleged fair uses: sampling, where users make temporary copies of a work before purchasing; space-shifting, where users access a sound recording through the Napster system that they already own in audio CD format; and permissive distribution of recordings by both new and established artists."[34] Judge Beezer found that Napster did not fit these criteria, instead enabling their users to repeatedly copy music, which would affect the market value of the copyrighted good.

The second claim by the plaintiffs was that Napster was actively contributing to copyright infringement since it had knowledge of widespread file sharing on their platform. Since Napster took no action to reduce infringement and financially benefited from repeated use, the Court ruled against the P2P site. The court found that "as much as eighty-seven percent of the files available on Napster may be copyrighted and more than seventy percent may be owned or administered by plaintiffs."[34]

The injunction ordered against Napster ended the brief period in which music streaming was a public good – non-rival and non-excludable in nature. Other P2P networks had some success at sharing MP3s, though they all met a similar fate in court. The ruling set the precedent that copyrighted digital content cannot be freely replicated and shared unless given consent by the owner, thereby strengthening the property rights of artists and record labels alike.[33]

Music streaming platforms[]

Although music streaming is no longer a freely replicable public good, streaming platforms such as Spotify, Deezer, Apple Music, SoundCloud, and Amazon Music have shifted music streaming to a club-type good. While some platforms, most notably Spotify, give customers access to a freemium service that enables the use of limited features for exposure to advertisements, most companies operate under a premium subscription model.[36] Under such circumstances, music streaming is financially excludable, requiring that customers pay a monthly fee for access to a music library, but non-rival, since one customer's use does not impair another's.

Music streaming platforms have grown rapidly in popularity in recent years. Spotify has over 207 million users, as of 1 January 2019, in 78 different countries,[37] Apple Music has about 60 million, and SoundCloud has 175 million.[38] All platforms provide varying degrees of accessibility. Apple Music and Prime Music only offer their services for paid subscribers, whereas Spotify and SoundCloud offer freemium and premium services. Napster, owned by Rhapsody since 2011, has resurfaced as a music streaming platform offering subscription based services to over 4.5 million users as of January 2017.[39] As music streaming providers have proliferated and competition has pushed the price of subscriptions down, music piracy rates have also fallen (see chart to the right).

The music industry's response to music streaming was initially negative. Along with music piracy, streaming services disrupted the market and contributed to the fall in revenue from $14.6 billion in revenue in 1999 to $6.3 billion in 2009 for the U.S. CD's and single-track downloads were not selling because content was freely available on the Internet. The result was that record labels invested more in artists that were "safe" – chart music became more appealing to producers than bands with unique sounds. In 2018, however, music streaming revenue exceeded that of traditional revenue streams (e.g. record sales, album sales, downloads).[40] 2017 alone saw a 41.1% increase in streaming revenue alone and an 8.1% increase in overall revenue.[40] Streaming revenue is one of the largest driving forces behind the growth in the music industry. In an interview, Jonathan Dworkin, a senior vice president of strategy and business development at Universal, said that "we cannot be afraid of perpetual change, because that dynamism is driving growth."[40]

COVID-19 pandemic[]

By August 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had streaming services busier than ever. In the UK alone, twelve million people joined a new streaming service that they had not previously had.[41]

An impact analysis of 2020 data by the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (CISAC) indicated that remuneration from digital streaming of music increased with a strong rise in digital royalty collection (up 16.6% to EUR 2.4 billion), but it would not compensate the overall loss of income of authors from concerts, public performance and broadcast.[42] The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) recompiled the music industry initiatives around the world related to the COVID-19. In its State of the Industry report, it recorded that the global recorded music market grew by 7.4% in 2022, the 6th consecutive year of growth. This growth was driven by streaming, mostly from paid subscription streaming revenues which increased by 18.5%, fueled by 443 million users of subscription accounts by the end of 2020.[43]

The COVID-19 pandemic has also driven an increase in misinformation and disinformation, particularly on streaming platforms like YouTube and podcasts.[44]

Technologies[]

Bandwidth[]

A broadband speed of 2 Mbit/s or more is recommended for streaming standard definition video without experiencing buffering or skips, especially live video,[45] for example to a Roku, Apple TV, Google TV or a Sony TV Blu-ray Disc Player. 5 Mbit/s is recommended for High Definition content and 9 Mbit/s for Ultra-High Definition content.[46] Streaming media storage size is calculated from the streaming bandwidth and length of the media using the following formula (for a single user and file): storage size in megabytes is equal to length (in seconds) × bit rate (in bit/s) / (8 × 1024 × 1024). For example, one hour of digital video encoded at 300 kbit/s (this was a typical broadband video in 2005 and it was usually encoded in a 320 × 240 pixels window size) will be: (3,600 s × 300,000 bit/s) / (8×1024×1024) requires around 128 MB of storage.

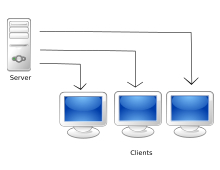

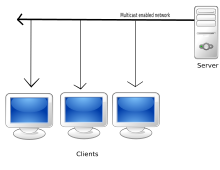

If the file is stored on a server for on-demand streaming and this stream is viewed by 1,000 people at the same time using a Unicast protocol, the requirement is 300 kbit/s × 1,000 = 300,000 kbit/s = 300 Mbit/s of bandwidth. This is equivalent to around 135 GB per hour. Using a multicast protocol the server sends out only a single stream that is common to all users. Therefore, such a stream would only use 300 kbit/s of serving bandwidth. See below for more information on these protocols. The calculation for live streaming is similar. Assuming that the seed at the encoder is 500 kbit/s and if the show lasts for 3 hours with 3,000 viewers, then the calculation is number of MBs transferred = encoder speed (in bit/s) × number of seconds × number of viewers / (8 × 1024 × 1024). The results of this calculation are as follows: number of MBs transferred = 500 x 1024 (bit/s) × 3 × 3,600 ( = 3 hours) × 3,000 (number of viewers) / (8 × 1024 × 1024) = 1,977,539 MB.[dubious ]

In 2018 video was more than 60% of data traffic worldwide and accounted for 80% of growth in data usage.[47][48]

Protocols[]

The audio stream is compressed to make the file size smaller using an audio coding format such as MP3, Vorbis, AAC or Opus. The video stream is compressed using a video coding format to make the file size smaller. Video coding formats include H.264, HEVC, VP8 or VP9. Encoded audio and video streams are assembled in a container "bitstream" such as MP4, FLV, WebM, ASF or ISMA. The bitstream is delivered from a streaming server to a streaming client (e.g., the computer user with their Internet-connected laptop) using a transport protocol, such as Adobe's RTMP or RTP. In the 2010s, technologies such as Apple's HLS, Microsoft's Smooth Streaming, Adobe's HDS and non-proprietary formats such as MPEG-DASH have emerged to enable adaptive bitrate streaming over HTTP as an alternative to using proprietary transport protocols. Often, a streaming transport protocol is used to send video from an event venue to a "cloud" transcoding service and CDN, which then uses HTTP-based transport protocols to distribute the video to individual homes and users.[49] The streaming client (the end user) may interact with the streaming server using a control protocol, such as MMS or RTSP.

The quality of the interaction between servers and users is based on the workload of the streaming service; as more users attempt to access a service, the more quality is affected unless there is enough bandwidth or the host is using enough proxy networks.[50] Deploying clusters of streaming servers is one such method where there are regional servers spread across the network, managed by a singular, central server containing copies of all the media files as well as the IP addresses of the regional servers. This central server then uses load balancing and scheduling algorithms to redirect users to nearby regional servers capable of accommodating them. This approach also allows the central server to provide streaming data to both users as well as regional servers using FFMpeg libraries if required, thus demanding the central server to have powerful data-processing and immense storage capabilities. In return, workloads on the streaming backbone network are balanced and alleviated, allowing for optimal streaming quality.[51]

Designing a network protocol to support streaming media raises many problems. Datagram protocols, such as the User Datagram Protocol (UDP), send the media stream as a series of small packets. This is simple and efficient; however, there is no mechanism within the protocol to guarantee delivery. It is up to the receiving application to detect loss or corruption and recover data using error correction techniques. If data is lost, the stream may suffer a dropout. The Real-time Streaming Protocol (RTSP), Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP) and the Real-time Transport Control Protocol (RTCP) were specifically designed to stream media over networks. RTSP runs over a variety of transport protocols, while the latter two are built on top of UDP.

Another approach that seems to incorporate both the advantages of using a standard web protocol and the ability to be used for streaming even live content is adaptive bitrate streaming. HTTP adaptive bitrate streaming is based on HTTP progressive download, but contrary to the previous approach, here the files are very small, so that they can be compared to the streaming of packets, much like the case of using RTSP and RTP.[52] Reliable protocols, such as the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), guarantee correct delivery of each bit in the media stream. However, they accomplish this with a system of timeouts and retries, which makes them more complex to implement. It also means that when there is data loss on the network, the media stream stalls while the protocol handlers detect the loss and retransmit the missing data. Clients can minimize this effect by buffering data for display. While delay due to buffering is acceptable in video on demand scenarios, users of interactive applications such as video conferencing will experience a loss of fidelity if the delay caused by buffering exceeds 200 ms.[53]

Unicast protocols send a separate copy of the media stream from the server to each recipient. Unicast is the norm for most Internet connections, but does not scale well when many users want to view the same television program concurrently. Multicast protocols were developed to reduce the server/network loads resulting from duplicate data streams that occur when many recipients receive unicast content streams independently. These protocols send a single stream from the source to a group of recipients. Depending on the network infrastructure and type, multicast transmission may or may not be feasible. One potential disadvantage of multicasting is the loss of video on demand functionality. Continuous streaming of radio or television material usually precludes the recipient's ability to control playback. However, this problem can be mitigated by elements such as caching servers, digital set-top boxes, and buffered media players.

IP Multicast provides a means to send a single media stream to a group of recipients on a computer network. A multicast protocol, usually Internet Group Management Protocol, is used to manage delivery of multicast streams to the groups of recipients on a LAN. One of the challenges in deploying IP multicast is that routers and firewalls between LANs must allow the passage of packets destined to multicast groups. If the organization that is serving the content has control over the network between server and recipients (i.e., educational, government, and corporate intranets), then routing protocols such as Protocol Independent Multicast can be used to deliver stream content to multiple Local Area Network segments. Peer-to-peer (P2P) protocols arrange for prerecorded streams to be sent between computers. This prevents the server and its network connections from becoming a bottleneck. However, it raises technical, performance, security, quality, and business issues.

Recording[]

Media that is livestreamed can be recorded through certain media players such as VLC player, or through the use of a screen recorder. Live-streaming platforms such as Twitch may also incorporate a video on demand system that allows automatic recording of live broadcasts so that they can be watched later.[54] The popular site, YouTube also has recordings of live broadcasts, including television shows aired on major networks. These streams have the potential to be recorded by anyone who has access to them, whether legally or otherwise.[55]

Applications and marketing[]

Useful – and typical – applications of streaming are, for example, long video lectures performed online.[56] An advantage of this presentation is that these lectures can be very long, although they can always be interrupted or repeated at arbitrary places. There are also new marketing concepts. For example, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra sells Internet live streams of whole concerts, instead of several CDs or similar fixed media, by their Digital Concert Hall[57] using YouTube for trailers. These online concerts are also spread over a lot of different places – cinemas – at various places on the globe. A similar concept is used by the Metropolitan Opera in New York. There also is a livestream from the International Space Station.[58][59] In video entertainment, video streaming platforms like Netflix, Hulu, and Disney+ are mainstream elements of the media industry.[60]

Marketers have found many opportunities offered by streaming media and the platforms that offer them, especially in light of the significant increase in the use of streaming media during COVID lockdowns from 2020 onwards. While revenue and placement traditional advertising continues to decrease, digital marketing increased in 15% in 2021[61], with digital media and search representing 65% of the expenditures.

A case study commissioned by the WIPO[62] indicates that streaming services attract advertising budgets with the opportunities provided with interactivity and the use of data from users, resulting in personalization on a mass scale with content marketing[63]. Targeted marketing is expanding with the use of artificial intelligence, in particular programmatic advertisement, a tool that helps advertisers decide their campaign parameters, and whether they are interested in buying advertising space online or not. One example of advertising space acquisition is Real-Time Bidding (RTB) [64].

Challenges[]

Copyright issues[]

The availability of large bandwidth internet enabled the audiovisual streaming services to attract large number of users around the world. For OTT platforms, original content represents a critical variable in order to capture more subscribers.[65] This generated a number of effects related to the copyright over the audiovisual content and its international exploitation through streaming such as contractual practices,[66] international exploitation of rights, widespread use of standards and metadata in digital files.[67] The WIPO has indicated the several basic copyright issues arising for those pursuing to work in the film[68] [69]and music industry[70] in the era of streaming.

Streaming copyrighted content can involve making infringing copies of the works in question. The recording and distribution of streamed content is also an issue for many companies that rely on revenue based on views or attendance.[71]

Greenhouse gas emissions[]

The net greenhouse gas emissions from streaming music have been estimated at between 200 and 350 million kilograms per year in the United States, according to a 2019 study.[72] This is an increase from emissions in the pre-digital music period, which were estimated at "140 million kilograms in 1977, 136 million kilograms in 1988, and 157 million in 2000."[73]

A 2021 study claims that one hour of streaming or videoconferencing "emits 150-1,000 grams of carbon dioxide ... requires 2-12 liters of water and demands a land area adding up to about the size of an iPad Mini." The study suggests that turning the camera off during video calls can reduce the greenhouse gas and water use footprints by 96%, and that an 86% reduction is possible by using standard definition rather than high definition when streaming content with apps such as Netflix or Hulu.[74]

One way to decrease greenhouse gas emissions associated with streaming music is making data centers carbon neutral, by converting to electricity produced from renewable sources. On an individual level, purchase of a physical CD may be more environmentally friendly if it is to be played more than 27 times.[75] Another option for reducing energy use can be downloading the music for offline listening, to reduce the need for streaming over distance.[75] The Spotify service has a built-in local cache to reduce the necessity of repeating song streams.[76]

See also[]

- Cloud gaming

- Comparison of music streaming systems

- Comparison of streaming media systems

- Comparison of video streaming aggregators

- Comparison of video hosting services

- Content delivery platform

- Digital Living Network Alliance (DLNA)

- Digital television

- Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market

- IPTV

- List of streaming media services

- List of streaming media systems

- Livestreaming

- Livestreamed news

- M3U playlists

- National Streaming Day

- Over-the-top media service

- P2PTV

- Protection of Broadcasts and Broadcasting Organizations Treaty

- Push technology

- Pro rata

- Real-time data

- Record label

- Stream processing

- Stream recorder

- Video over cellular

- Web syndication

References[]

- ^ Gelman, A.D.; Halfin, S.; Willinger, W. (1991). "On buffer requirements for store-and-forward video on demand service circuits". IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference GLOBECOM '91: Countdown to the New Millennium. Conference Record. IEEE. pp. 976–980. doi:10.1109/GLOCOM.1991.188525. ISBN 0-87942-697-7. S2CID 61767197.

- ^ Reason, Samuel (6 November 2020). "Music Streaming Actually Existed Back In 1890". blitzlift.com. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ US 1,641,608, "Electrical signaling"

- ^ Greene, Bob. "GETTING PERSONAL WITH THE JUKEBOX". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ a b Furness, Zack (17 October 2019). "Did You Know Music Streaming Has Roots in Pittsburgh?". pittsburghmagazine.com. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Bradley-Steck, Tara (4 September 1988). "Complex Link-Up of Phone Lines, Old Phonograph Records : 'Human Jukebox' Spins Sounds for the Heart". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Lee, Jack (2005). Scalable Continuous Media Streaming Systems: Architecture, Design, Analysis and Implementation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 25. ISBN 9780470857649.

- ^ "History of the Internet Pt. 1 – The First Live Stream". From YouTube.com. Internet Archive – Stream Division. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "RealNetworks Inc". Funding Universe. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Cyberian Rhapsody". Billboard. United States: Lynne Segall. 17 February 1996.

- ^ Tobagi, F.A.; Pang, J. (1993). "Star Works-a video applications server". Digest of Papers. Compcon Spring. pp. 4–11. doi:10.1109/CMPCON.1993.289623. ISBN 0-8186-3400-6. S2CID 61039780.

- ^ "Starlight Networks and Hughes Network Systems". Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ Hebert, Steve (November 2000). "Streaming Video Opens New Doors". Videography. p. 164.

- ^ Reinstein, Bill (25 June 2001). "Webcasts Mature as Marketing Tool". DM News. p. 24.

- ^ "YouTube now defaults to HTML5 <video>". YouTube Engineering and Developers Blog. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Josh Lowensohn (2008). "YouTube to Offer Live Streaming This Year". Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "YouTube Video Speed History". YouTube. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "News and Notes on 2015 RIAA Shipment and Revenue Statistics" (PDF). RIAA. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "Streaming made more revenue for music industry in 2015 than digital downloads, physical sales". The Washington Times. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Shaw, Lucas (20 September 2016). "The Music Industry Is Finally Making Money on Streaming". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "Streaming Wars". The Verge. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ "Streaming wars (Creative Economy Notes Series)". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Masnick; M.; Ho, M.; Hung, J.; Beadon, L. "The Sky is Rising" (PDF). Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (20 November 2018). "Xgau Sez". robertchristgau.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Grant and Meadows. (2009). Communication Technology Update and Fundamentals 11th Edition. pp.114

- ^ Kellner, Scott (28 February 2013). "The Future of Webcasting". INXPO. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Umstead, R. Thomas (5 June 2017). "Horowitz: Streaming Is the New Normal". Broadcasting & Cable: 4.

- ^ Steel, Emily (26 July 2015). "Netflix Refines Its DVD Business, Even as Streaming Unit Booms". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "Ashes to ashes, peer to peer: An oral history of Napster". Fortune. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ 31 May, Benny Evangelista on; PM, 2009 at 8:00 (1 June 2009). "An interview with Napster's Shawn Fanning". The Technology Chronicles. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ a b expertise, Mark Harris Brings music; Producer, Including a Background as a Music; composer; Articles, To Digital Music. "The History of Napster: Yes, It's Still Around". Lifewire. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (18 February 2002). "Record Labels' Answer to Napster Still Has Artists Feeling Bypassed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Case Study: A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc. – Blog | @WashULaw". onlinelaw.wustl.edu. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "A&M RECORDS, INC. v. NAPSTER, INC., 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir. 2001)". law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Digital Media Association Annual Report" (PDF). March 2018.

- ^ "Battle of the Streaming Services: Which Is the Best Premium Video Service?". NDTV Gadgets 360. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Spotify 2018 Quarter 4 Letter to Shareholders" (PDF). Spotify.

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh. "The Top 10 Streaming Music Services By Number Of Users". Forbes. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Napster Proves That Streaming Music Can Be Profitable". Digital Music News. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "Global Music Report 2018: Annual State of the Industry" (PDF). GMR. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Rajan, Amol (5 August 2020). "TV watching and online streaming surge during lockdown". BBC News. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ CISAC. "CISAC Global Collections Report 2021 (for 2020 Data)". CISAC. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "IFPI issues Global Music Report 2021: Global recorded music revenues grow 7.4%". IFPI.org. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Hsu, Tiffany; Tracy, Marc (12 November 2021). "On Podcasts and Radio, Misleading Covid-19 Talk Goes Unchecked". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Staples, Kim (20 May 2016). "How to watch live TV online: The complete guide". broadbandchoices. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ Minimum requirements for Sony TV Blu-ray Disc Player, on advertisement attached to a NetFlix DVD[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "The myth of the green cloud". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Cisco Annual Internet Report - Cisco Annual Internet Report (2018–2023) White Paper". Cisco. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Streaming the London Olympic Games with the 'Go Live Package' from iStreamPlanet and Haivision | iStreamPlanet". www.istreamplanet.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ Sripanidkulchai, Kunwadee; Maggs, Bruce; Zhang, Hui (2004). "An Analysis of Live Streaming Workloads on the Internet". Proceedings of the 4th ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement. IMC '04. New York, NY, USA: ACM: 41–54. doi:10.1145/1028788.1028795. ISBN 9781581138214. S2CID 1742312.

- ^ Zhao, Hong; Chun-long, Zhou; Bao-zhao, Jin (3 February 2015). "Design and Implementation of Streaming Media Server Cluster Based on FFMpeg". The Scientific World Journal. 2015: 963083. doi:10.1155/2015/963083. PMC 4334929. PMID 25734187.

- ^ Ch. Z. Patrikakis, N. Papaoulakis, Ch. Stefanoudaki, M. S. Nunes, "Streaming content wars: Download and play strikes back" presented at the Personalization in Media Delivery Platforms Workshop, [218 – 226], Venice, Italy, 2009.

- ^ Krasic, C. and Li, K. and Walpole, J., The case for streaming multimedia with TCP, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 213–218, Springer, 2001

- ^ "Videos On Demand". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ Burroughs, Benjamin; Rugg, Adam (3 July 2014). "Extending the Broadcast: Streaming Culture and the Problems of Digital Geographies". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 58 (3): 365–380. doi:10.1080/08838151.2014.935854. ISSN 0883-8151. S2CID 144577408.

- ^ A typical one-hour video lecture is the following live stream from an international conference on financial crises: /videolectures.net

- ^ "The Berliner Philharmoniker's Digital Concert Hall". Digital Concert Hall.

- ^ "High Definition Earth-Viewing System (HDEV)". NASA. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "ISS HD Earth Viewing Experiment". Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Forrester. "Q1 2020 Proves Streaming Is Essential To Consumers And To The Future Of Media Companies". Forbes. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Deloitte study: digital marketing spending is expected to increase by almost 15% until the end of 2021, while traditional advertising will slightly decrease". Deloitte Romania. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Ms. Leticia Ange Pozza and Ms. Ana Paola Sifuentes. "Case Study VI: Data in the Audiovisual business: Trends and Opportunities" (PDF). WIPO website. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Revised Proposal for a Pilot Project on Copyright and the Distribution of Content in the Digital Environment Submitted by Brazil". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "What is programmatic video advertising? (And why it's smart to use it)". Biteable. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Katz, Raul (October, 2021). Study on the copyright legal framework and licensing practices of audiovisual content in the digital environment, Part 1: Audiovisual OTT business models in Latin America: Recent trends and future evolution. https://www.wipo.int/ip-development/en/agenda/work_undertaken.html#pilot_project_cdcde World Intellectual Property Organization

- ^ Moullier, B; Galvis, Alexandra (October, 2021). Study on the copyright legal framework and licensing practices of audiovisual content in the digital environment, Part 4: contractual practices in the Latin American audiovisual sector in the digital environment. World Intellectual Property Organization https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/ip-development/en/agenda/pdf/part_4_contractual_practices_latin_american_audiovisual_sector_digital_environment.pdf

- ^ Schotz, Gustavo (October, 2021). Study on the copyright legal framework and licensing practices of audiovisual content in the digital environment, Part 5: The Identification and Use of Metadata in Audiovisual Works https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/ip-development/en/agenda/pdf/11_part_5_identification_and_metadata_av-en.pdf. World Intellectual Property Organization

- ^ WIPO, How to make a living in the Film Industry. Available at: How to Make a Living in the Film Industry https://www.wipo.int/copyright/en/creative_industries/film.html (wipo.int)

- ^ WIPO, How to make a living in the Film Industry. Rights, Camera, Action! https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/copyright/869/wipo_pub_869.pdf (wipo.int)

- ^ WIPO, How to make a living in the Music Industry. Available at: How to Make a Living in the Music Industry https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/copyright/939/wipo_pub_939.pdf (wipo.int)

- ^ Maeda, Mari (17 March 2001). "The internet of the future". Optical Fiber Communication Conference and International Conference on Quantum Information (2001), Paper TuK1. Optical Society of America: TuK1. doi:10.1364/OFC.2001.TuK1. ISBN 1-55752-654-0.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (23 May 2019). "Is Streaming Music Dangerous to the Environment? One Researcher Is Sounding the Alarm". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ "Music consumption has unintended economic and environmental costs". The University of Glasgow. 8 April 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ "Turn off that camera during virtual meetings, environmental study says: Simple tips to go green with your internet use during a pandemic". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ a b McKay, Deirdre; George, Sharon (10 January 2019). "The environmental impact of music: digital, records, CDs analysed". The Conversation. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Andrews, Robert (12 September 2012). "Streaming media could have larger carbon footprint than plastic discs". gigaom.com. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

Further reading[]

- Hagen, Anja Nylund (2020). Music in Streams: Communicating Music in the Streaming Paradigm, In Michael Filimowicz & Veronika Tzankova (ed.), Reimagining Communication: Mediation (1st Edition). Routledge.

- Preston, J. (11 December 2011). "Occupy Video Showcases Live Streaming". The New York Times.

- Sherman, Alex (27 October 2019). "AT&T, Disney and Comcast have very different plans for the streaming wars – here's what they're doing and why". CNBC.

External links[]

- "The Early History of the Streaming Media Industry and The Battle Between Microsoft & Real". streamingmedia.com. March 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- "What is Streaming? A high-level view of streaming media technology, history". streamingmedia.com. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Streaming media systems

- Applications of distributed computing

- Cloud storage

- File sharing networks

- Film and video technology

- Peer-to-peer computing

- Peercasting

- Television terminology

- Promotion and marketing communications

- Bundled products or services