Sum of public power

The neutrality of this article is disputed. (January 2013) |

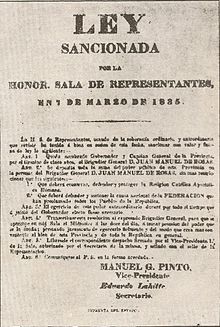

| Sum of Public Power | |

|---|---|

Ruling of the Legislature | |

| Created | 1835 |

| Signatories | Legislature of Buenos Aires |

The sum of public power (Spanish: Suma del poder público) is a legal term from Argentina, included in its constitution. It represents the sum of the three powers, and deems the complete delegation of them into the executive power as a crime of high treason.

The term was created in 1835, when governor Juan Manuel de Rosas was granted such powers by the legislature of Buenos Aires. Justo José de Urquiza led an army to depose Rosas in order to enact a Constitution, which Rosas had delayed for years, and the 1853 Constitution legally forbade such a thing from happening again.

Historical context[]

The death of the federalist caudillo Facundo Quiroga caused great concern in the Argentine Confederation, and soon the legislature of Buenos Aires elected Rosas as governor. A law from August 3, 1821, allowed the legislature to grant those powers.[1] Those powers were fully delegated on him, with the sole exceptions of keeping, defending and protecting the Roman Catholic Church, and keeping and defending the cause of the Confederation.[2] The term of office of the governor, of three years, was extended to five years. The legislature reelected Rosas three times, allowing him three full mandates of 5 years, being overthrown during the fourth. Rosas could use the sum of public power during any time period he deemed convenient during his mandate.[1]

To confirm the legitimacy of his mandate, Rosas requested a vote to approve or reject him. Although there was no universal suffrage in Argentina by then, Rosas requested that all the people in Buenos Aires was allowed to vote, regardless of wealth or social conditions. This proposal was influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau's The Social Contract. The only ones who could not vote were the women, the slaves, children under 20 years old (unless emancipated) and foreigners without a stable residence in the country. The final result had 9720 votes for Rosas and only 8 against him.[3]

Nature[]

Although Rosas received the sum of public power, he did not become an absolute monarch. He still had a limited term of office, and the legislature and other republican institutions were kept.[4]

It was not a tyranny either, as he did not have the usual traits of a tyranny. He did not take the power by an illegal way, such as a coup d'état, but by an appointment of the legislature, and no law prevented the legislature from doing what it did. He did not become governor against the will of the population, as it was confirmed by a popular vote. He did not rule on behalf of a social minority, either.[4]

His appointment was in line with the ideas of Rousseau, who thought that "If, on the other hand, the peril is of such a kind that the paraphernalia of the laws are an obstacle to their preservation, the method is to nominate a supreme ruler, who shall silence all the laws and suspend for a moment the sovereign authority. In such a case, there is no doubt about the general will, and it is clear that the people's first intention is that the State shall not perish".[5] This principle influenced as well the concept of the state of emergency, included in the 1853 constitution and in most legal systems around the world.[6]

Actual usage[]

Rosas did not fully use the powers invested in him. He did not close the legislature, which continued working during his rule. He was not interested in the tasks of the judiciary power, so he did not use any judiciary powers after the end of the trial about the death of Facundo Quiroga. Even more, the governor used to be the highest court of appeal since the times of Spanish authority, so the legislature sanctioned a law in 1838 that established the "Tribunal Supremo de Recursos Extraordinarios", so that the highest court of the judiciary was still outside the executive power. Rosas gave his consent to the new law immediately.[7]

Controversy[]

The delegation of the sum of public power on Rosas was highly controversial. Domingo Faustino Sarmiento compared Rosas with other historical dictators in his work Facundo, where he said as follows:

Once being owner of absolute power, who will ask him for it later? Who will dare to dispute his titles to the domination? The Romans gave the dictatorship in rare cases and for short-term, fixed durations, and yet the use of temporary dictatorship allowed the perpetual one that destroyed the Republic and brought all the wildness of the Empire. When the term of government expires Rosas announces his resolute determination to retire to private life, the death of his beloved wife, his father, had ulcerated his heart and needs to go away from the tumult of public affairs to mourn the wide losses as bitter. The reader should recall hearing this language in the mouths of Rosas, that he had not seen his father since his youth, and whose wife had been such bitter days, something like the hypocritical protests of Tiberius to the Roman Senate. The Board of Buenos Aires pleads, begs him to continue making sacrifices for their country, Rosas is left to persuade, still only six months, spending six months and leaves the farce of the election. And indeed, what need has been elected a leader who has entrenched the power in his person? Who asks trembling from the terror that has inspired all of them?[8]

On the contrary, José de San Martín gave his full support to the delegation, on the grounds that the current situation in the country was so chaotic that it was needed to create order.

Men do not live from dreams but from facts. What I care if it is repeated over and over again that I live in a country of liberty, if on the contrary, I'm being oppressed? Freedom!, Give it to a child of two years for enjoying by way of fun with a box of razor blades and you tell me the results. Freedom! So that if I devote myself to any kind of industry, comes a revolution that destroy the work of many years and the hope of leaving a loaf of bread for my children. Freedom! In order to charge me for contributions to pay the huge costs incurred, for four ambitious because they feel like, by way of speculation, making a revolution and go unpunished. Freedom! For the bad faith to found complete impunity as proved by the generality of bankruptcies ... this freedom, nor is the son of my mother going to enjoy the benefits it provides, until you see established a government that demagogues called tyrant, and protect me against the properties that freedom gives me today. Maybe you may tell that this letter is written in a good soldierly humor. You will be right, but you agree that at age 53 one can not admit that good faith will want to take for a ride ... Let this matter conclude and let me end by saying that the man who set the order of our country, whatever the means that for it employees, is the only one that would deserve the noble title of Liberator.[9]

Constitutional status[]

Rosas's mandate ended after his defeat at the Battle of Caseros, and Urquiza called for the making of a National Constitution, which was written the following year, 1853. The 29º article explicitly forbids a delegation of powers such as the one done with Rosas to be performed.

Congress can not give the National Executive, nor the provincial legislatures to governors of provinces, extraordinary powers, nor the sum of public power, nor may grant submission or supremacy whereby the life, the honor, or wealth of the Argentine people will be at mercy of governments or individual. Acts of this nature shall be utterly void, and shall render those who formulate, consent to or sign them, liable to be condemned as infamous traitors to the motherland.[10]

However, the penalty for the 1835 release of the public power to Rosas is not affected by this ruling, as the Constitution was not established back then and had no ex post facto law provisions.[11]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jaime Galvez, p. 32

- ^ Decreto concediendo la suma del poder público a Rosas (in Spanish)

- ^ Jaime Galvez, p. 37

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jaime Galvez, p. 38

- ^ Rousseau, p. 84

- ^ Jaime Gálvez, p. 39

- ^ Jaime Gálvez, p. 40

- ^ Facundo

- ^ San Martín Confidencial

- ^ Constitución Nacional Argentina Archived 2013-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jaime Gálvez, pp. 36-37

Bibliography[]

- Félix Luna; Arturo Jauretche; Benjamín Villegas Basavilbaso; Jaime Gálvez; León Rebollo Paz; Fermín Chávez; José Antonio Ginzo; Luis Soler Cañas; Arturo Capdevilla; Julio Irazusta; Enrique de Gandia; Ernesto Palacio; Bernardo González Arrili; Emilio Ravignani; José Antonio Saldías; Arturo Orgaz; Manuel Gálvez; Diego Luis Molinari; Ricardo Font Ezcurra; Héctor Pedro Blomberg; Ramón Doll; Adolfo Mitre; Rafael Padilla Rorbón; Alberto Gerchunoff; Mariano Bosch; Ramón de Castro Ortega; Carlos Steffens Soler; Julio Donato Álvarez; Roberto de Laferrere; Justiniano de la Fuente; Federico Barbará; Ricardo Caballero (2010). Con Rosas o contra Rosas (in Spanish). Santa Fe: H. Garetto Editor. ISBN 978-987-1493-15-9.

- Rousseau, Jean Jacques (2004). The social contract or principles of political right. Kessinger Publishing.

- Juan Manuel de Rosas

- Argentine law

- Argentine Civil War

- Emergency laws

- 1835 in law

- 1835 establishments in Argentina