Superkilen

Superkilen is a public park in the Nørrebro district of Copenhagen, Denmark. The park is designed to bring refugees and locals together, promoting tolerance and unity[1] in one of Denmark's most ethnically-diverse and socially-challenged communities.[2] Not only is the park a meeting place for local residents, it is a tourist attraction for Copenhagen.[3] Designed by the arts group Superflex with the collaboration of Bjarke Ingels Group and , a German landscape architecture firm, the park was officially opened in June 2012.[4] The almost kilometre-long[5] park's name refers to its shape, "kilen" meaning "wedge".[2]

Background[]

The park is part of an urban improvement plan coordinated by the City of Copenhagen in a partnership with Realdania, a private philanthropic organization.[6] The objective was to upgrade the Nørrebro neighbourhood to a high standard of urban development liable to inspire other cities and districts.[7] It is designed as a kind of world exposition for the local inhabitants, covering over 60 nationalities, who have been able to contribute their own ideas and artefacts to the project.[4]

Nørrebro is a neighbourhood plagued by crime and areas to the East and West of the park's location were cut off from the rest of the city by two major highways.[6] It was also the site of riots in 2006 triggered by a controversial cartoon.[8] The Copenhagen-based architects experienced the vandalism and violence of these riots in the streets outside their office, just after designing a downtown mosque, and decided to focus on creating urban spaces to promote integration across ethnicity, religion, culture, and languages.[9]

The designers see the park as not a finite project but an "artwork in progress."[8] The design is based on dreams that could transform into objects and is meant to make people of diverse backgrounds feel at home.[10] It uses humour to represent the different cultures in a respectful manner.[10]

Commissioned in June 2008, the design process lasted from January 2009 until February 2010, with construction between August 2010 and June 2012.[2] The project cost $8,879,000 USD.[2]

Awards and recognition[]

The project was rewarded with a 2013 AIA Honor Award in the Regional & Urban Design category by the American Institute of Architects.[11] It was shortlisted for Design of the Year by the Design Museum in London[12] as well as for the European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture.[13] Superkilen was also one of six winners of the 2016 Aga Khan Award for Architecture[14] recognized for promoting integration of the various religious and ethnic groups living in the area[15] despite tensions between immigrant and host populations,[16] with a mix of humour, history, and hubris.[17]

Various tourist platforms list the park as one of Copenhagen's top ten must-visit sites.[8] Many advertisements have used the park as a background.[8]

Features[]

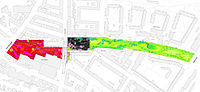

Stretching some 750 metres (2,460 ft) along either side of a public cycle track and covering a total area of some 30,000 square metres (320,000 sq ft), Superkilen is made up of three main areas: a red square, a black market and a green park. While the red square, painted bright red, orange and pink, focuses on recreation and modern living, the black market at the centre is the classic square with a fountain where neighbours can meet, with its barbecue grills and palm trees from China, an "urban living room".[2] The green park, literally entirely green, has rolling hills, trees and plants suitable for picnics, sports and dog-walking.[18][19]

Many of the objects in the park have been specially imported or copied from foreign designs. They include swings from Iraq, benches from Brazil, a fountain from Morocco and litter bins from England.[18] There are neon signs from throughout the world advertising everything from a Russian hotel to a Chinese beauty parlour. Even the manhole covers come from Zanzibar, Gdansk and Paris. In all, there are 108 plants and artefacts illustrating the ethnic diversity of the local population,[20] whose backgrounds touch 62 different countries.[2] These objects help symbolize residents' shared ownership of the park.[6]

A plate on the ground next to each item describes it in Danish and the language of its home country,[3] and visitors can download an app to learn more about each object.[8]

Furnishings and activities[]

- Moroccan fountain: star-shaped,[2] provides a place where parents can sit and chat while their kids play [10]

- Skateboard ramps[21]

- Basketball hoops: from Mogadishu[6]

- Hockey[3]

- Exercise equipment: from Muscle Beach in Los Angeles, USA[6]

- Gymnastic rings: meet new friends and training partners[22]

- Green Park children's playground[10]

- Swings: mothers bring their children to play[21]

- Double swings[10]

- Swing bench: from Baghdad[10]

- Octopus: represents Japan and acts as a play area for children[10]

- Playground from India[10]

- Elephant slide: from Chernobyl[10]

- Walking: the park is described as a "highly walkable experience"[21]

- Bike path[10]

- Chess tables: represents Bulgaria and connects elderly people with young children of diverse backgrounds[10]

- Red square: open surface for community-organized cultural activities such as open-air concerts, cultural mixers, and storytelling events[10]

- Black Market white stripes: visually striking, parallel yet diverging, meant to guide people toward objects.[10]

- Inspired by the Lars von Trier film "Dogville."[10]

- Black Market food market[10]

- Cafes and retail spaces[6]

- Black Market picnic area[10]

- Armenian picnic tables[10]

- Pergola: inspired by a dance pavilion in St. Louis, USA[10]

- Bus stop from Kazakhstan[10]

- German bench[10]

- Bench from Switzerland[10]

- Romanian stools[10]

- Drain cover from Israel[3]

- 3 tonnes of soil from the Palestinian Territories:[23] inspired by two teenage girls who had never touched their home soil.[8]

Social impact[]

Superkilen has succeeded in joining two residential areas formerly divided by a fence[24] and has reconnected the surrounding areas to the rest of the city.[6] Pedestrian and cycling traffic has increased[24] between two major roads[6] and the park encourages people to become more active.[10] It provides a stimulating environment, particularly important for children.[10]

The park acts as a meeting place for residents of Denmark's most ethnically-diverse neighbourhood and attracts visitors from across the city and around the world.[25] It has rejuvenated the problematic area and brought together the sixty different nationalities living nearby.[22] In addition to the wide range of ethnicities using the park, it attracts a wide range of ages, from small children with their parents to elderly people.[26]

Although the area has a history of vandalism, this has not been a huge issue in the park.[26] Lighting in the area helps create a sense of security for residents.[6] Some area residents were initially concerned that it would not be a traditional green park, but are generally pleased with gaining a meeting place and the park's high level of activity, and are proud of their neighbourhood park.[26] Adding green space to the neighbourhood has aided water management.[26]

Design process[]

Instead of designing the park with traditional public outreach catering to political correctness and preconceived ideas, the architects used extreme public participation to drive the park's design.[3] They reached out to residents using internet, email, newspapers, and radio.[27] The public consultation process was extensive, gathering suggestions from area residents for objects the park could contain to represent all sixty nationalities,[3] then a local governance board selected the objects.[2] Diversity was less a problem requiring a solution than a useful tool in the creative process of creating the park's identity.[2]

Gallery[]

Palm trees

Red area cycle track

Russian pavilion

Japanese octopus

Armenian picnic tables

Red area

Moroccan fountain

References[]

- ^ "Danish park designed to promote tolerance in community wins architectural award". Reuters. 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2016 Winning Projects" (PDF). Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Superkilen". Archnet. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Superkilen" Archived 2012-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Københavns Kommune. (in Danish) Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ AFP (2016-11-07). "Six projects awarded Aga Khan architecture prize". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Aga Khan Award for Architecture" (PDF). Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Sebastian Jordana, "In Progress: Superkilen / BIG and Topotek 1", ArchDaily, 18 Aug 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Superkilen" (PDF). Superkilen Information sheet. Municipality of Copenhagen.

- ^ "Superkilen". Archnet. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Superkilen | Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- ^ "2013 AIA Institute Honor Awards - Regional & Urban Design". Bustler. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ "Designs of the Year 2013 Nominations". World Landscape Architecture. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ "Five Finalists for 2013 EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture - Mies van der Rohe Award". Bustler. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ^ http://www.washingtontimes.com, The Washington Times. "China, Denmark projects among architecture award winners". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

- ^ AP (2016-10-04). "China, Denmark projects among architecture award winners". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

- ^ "Danish park designed to promote tolerance in community wins architectural award". Reuters. 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

- ^ Winners of Aga Khan architecture award announced - VIDEO, retrieved 2019-12-28

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bonnie Fortune, "So many people lent a hand to give us parklife!", Copenhagen Post, 15 January 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Tools/Superkilen", Superflex. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ (in Danish) Karsten Ifversen, "Superkilen, der indvies i dag, er en skæg antropologisk have", Politiken, 22 June 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Browning, Noah (2016-10-04). "Danish park designed to promote tolerance in community wins architectural award". The Star Online. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "What's special about this Copenhagen park?". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ "What's special about this Copenhagen park?". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "2016 On Site Review Report Superkilen, Copenhagen, Denmark" (PDF). Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Muiruri, Peter. "'Green' buildings top awards". The Standard. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Akšamija, Azra. "2016 On Site Review Report" (PDF). Aga Khan Award for Architecture Report.

- ^ "Superkilen" (PDF). Retrieved 15 December 2019.

Further reading[]

- Daly, J. (2019) "Superkilen: exploring the human–nonhuman relations of intercultural encounter", in Journal of Urban Design.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Superkilen. |

- Superflex project description

- Article at The Atlantic Cities

Coordinates: 55°42′00″N 12°32′45″E / 55.70000°N 12.54583°E

- Parks in Copenhagen

- Squares in Copenhagen

- Bjarke Ingels buildings

- Linear parks