The 120 Days of Sodom

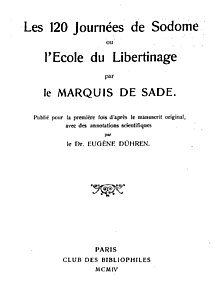

Title page of Les 120 Journées de Sodome, first edition, 1904 (Paris) | |

| Editor | Dr. Eugen Dühren |

|---|---|

| Author | Marquis de Sade |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Subject | Sadism |

| Genre | Erotic fiction, philosophical literature |

| Publisher | Club des Bibliophiles (Paris) Penguin Books (recent English edition) |

Publication date | 1904 |

Published in English | Unknown |

| Media type | Print (Manuscript) |

| ISBN | 978-0141394343 (recent edition) |

| OCLC | 942708954 |

The 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinage[1] (French: Les 120 Journées de Sodome ou l'école du libertinage) is a novel by the French writer and nobleman Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade. Described as both pornographic[2] and erotic,[3] it was written in 1785.[4] It tells the story of four wealthy male libertines who resolve to experience the ultimate sexual gratification in orgies. To do this, they seal themselves away for four months in an inaccessible castle in the heart of the Black Forest,[4] with a harem of 36 victims, mostly male and female teenagers, and engage four female brothel keepers to tell the stories of their lives and adventures. The crimes and tortures in the women's narratives inspire the libertines to similarly abuse and torture their victims, which gradually grows in intensity and ends in their slaughter.

The novel was never completed; it exists mainly in rough draft and note form. Sade wrote it in secrecy while imprisoned in the Bastille in 1785; shortly after he was transferred elsewhere the Bastille was attacked by revolutionaries, leading him to believe the work was destroyed, but it was instead recovered by a mysterious figure and preserved long enough thereafter to become available in the early 20th century.[5] It was not until the latter half of the 20th century that it became more widely available in countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States and France.[2] Since then, it has been translated into many languages, including English, Japanese, Spanish, Russian, and German. It remains a highly controversial book, having been banned by some governments due to its explicit nature and themes of sexual violence and extreme cruelty, such as in the UK in the 1950s,[6] but remains of significant interest to students and historians.[5] In 2016 an English translation of the work became a Penguin Classic.[6]

Plot[]

The 120 Days of Sodom is set in a remote medieval castle, high in the mountains and surrounded by forests, detached from the rest of the world, either at the end of Louis XIV's reign or at the beginning of the Régence.

The novel takes place over five months, November to March. Four wealthy libertines lock themselves in a castle, the Château de Silling, along with a number of victims and accomplices (the description of Silling matches de Sade's own castle, the Château de Lacoste). Since they state that the sensations produced by the organs of hearing are the most erotic, they intend to listen to various tales of depravity from four veteran prostitutes, which will inspire them to engage in similar activities with their victims.

The novel is notable for not existing in a complete state, with only the first section being written in detail. After that, the remaining three parts are written as a draft, in note form, with de Sade's notes to himself still present in most translations. Either at the outset, or during the writing of the work, de Sade had evidently decided he would not be able to complete it in full and elected to write out the remaining three-quarters in brief and finish it later.

The story does portray some black humor, and de Sade seems almost light-hearted in his introduction, referring to the reader as "friendly reader". In this introduction, he contradicts himself, at one point insisting that one should not be horrified by the 600 passions outlined in the story because everybody has their own tastes, but at the same time going out of his way to warn the reader of the horrors that lie ahead, suggesting that the reader should have doubts about continuing. Consequently, he glorifies as well as vilifies the four main protagonists, alternately declaring them freethinking heroes and debased villains, often in the same passage.

Characters[]

The four principal characters are wealthy men, who are libertine, ruthless, and each "lawless and without religion, whom crime amused, and whose only interest lay in his passions ... and had nothing to obey but the imperious decrees of his perfidious lusts." It is no coincidence that they are authority figures in terms of their occupations. De Sade despised religion; in the chateau of the 120 Days, toilet activities must be performed in the chapel. He also opposed authority, and in many of his works he enjoyed mocking religion and authority by portraying priests, bishops, judges, and the like as sexual perverts and criminals.

The four men are:

- The Duc de Blangis – aged 50, an aristocrat who acquired his wealth by poisoning his mother for the purposes of inheritance, prescribing the same fate to his sister when she found out about his plot. Blangis is described as being tall, strongly built, and highly sexually potent, although it is emphasised that he is a complete coward and proud of it.

- The Bishop (l’Évêque) – Blangis's brother. He is 45, a scrawny and weak man "with a nasty mouth". He greatly enjoys sodomy (anal sex), especially passive sodomy. He enjoys combining murder with sex. He refuses to have vaginal intercourse.

- The Président de Curval – aged 60, a tall and lanky man "frightfully dirty about his body and attaching voluptuousness thereto". He is so encrusted with bodily filth that it adds inches to the surface of his penis and anus. He used to be a judge and especially enjoyed handing out death sentences to defendants he knew to be innocent. He murdered a mother and her young daughter.

- Durcet – aged 53, a banker described as short and pale, with a portly, markedly feminine shape, although well kept and firm-skinned. He is effeminate and enjoys receiving anal sex from men above any other sexual activity. Like his cohorts, he has been responsible for several murders.

Their accomplices are:

- Four accomplished prostitutes, middle-aged women who will relate anecdotes of their depraved careers to inspire the four principal characters into similar acts of depravity.

- Madame Duclos, 48, witty, and still fairly attractive and well-kept.

- Madame Champville, 50, a lesbian, partial to having her 3-inch (8 cm) clitoris tickled; she is a vaginal virgin, but her rear is flabby and worn from use, so much so that she feels nothing there.

- Madame Martaine, 52, especially excited by anal sex; a natural deformity prevents her from having any other kind.

- Madame Desgranges, 56, pale and emaciated, with dead eyes, whose anus is so enlarged she does not feel anything there. She is missing one nipple, three fingers, six teeth, and an eye. By far the most depraved of the four; a murderer, rapist, and general criminal.

- Eight studs (French: fouteurs, "fuckers") who are chosen solely because of their large penises.

- Hercule, 26

- Antinoüs, 40

- Brise-Cul ("break-arse")

- Bande-au-ciel ("erect-to-the-sky")

The victims are:

- The daughters of the four principal characters, whom they have been sexually abusing for years. All of them die with the exception of the Duc's daughter Julie, who is spared after becoming something of a libertine herself.

- Eight boys and eight girls aged from 12 to 15. All have been kidnapped and chosen because of their beauty. They are also all virgins and the four libertines plan on deflowering them, vaginally and especially anally. In the selection process, the boys are dressed as girls to help the four in making selections.

- The girls:

- Augustine, 15

- Fanny, 14

- Zelmire, 15

- Sophie, 14

- Colombe, 13

- Hébé, 12

- Rosette, 13

- Mimi, 12

- The boys:

- Zélamir, 13

- Cupidon, 13

- Narcisse, 12

- Zephyr, 12

- Celadon, 14

- Adonis, 15

- Hyacinthe, 14

- Giton, 12

- Four middle-aged women, chosen for their ugliness to stand in contrast to the children.

- Marie, 58, who strangled all 14 of her children and one of whose buttocks is consumed by an abscess.

- Louison, 60, stunted, hunchbacked, blind in one eye and lame.

- Thérèse, 62, has no hair or teeth. Her anus, which she has never wiped in her whole life, resembles a volcano. All of her orifices stink.

- Fanchon, 69, short and heavy, with hemorrhoids the size of a fist hanging from her anus. She is usually drunk, vomits constantly, and has fecal incontinence.

- Four of the eight aforementioned studs.

There are also several cooks and female servants, those in the latter category later being dragged into the proceedings.

History[]

[needs update]

Sade wrote The 120 Days of Sodom in the space of 37 days[citation needed] in 1785 while he was imprisoned in the Bastille. Being short of writing materials and fearing confiscation, he wrote it in tiny writing on a continuous roll of paper, made up of individual small pieces of paper smuggled into the prison and glued together. The result was a scroll 12 metres long that Sade would hide by rolling it tightly and placing it inside his cell wall. Sade incited a riot among the people gathered outside when he shouted to them that the guards were murdering inmates; as a result, two days later on 4 July 1789, he was transferred to the asylum at Charenton, "naked as a worm" and unable to retrieve the novel in progress. Sade believed the work was destroyed when the Bastille was stormed and looted on 14 July 1789, at the beginning of the French Revolution. He was distraught over its loss and wrote that he "wept tears of blood" in his grief.[7]

However, the long scroll of paper on which it was written was found hidden in the walls of his cell where Sade had left it, and removed two days before the storming by a citizen named Arnoux de Saint-Maximin.[7] Historians know little about Saint-Maximin or why he took the manuscript.[7] It was first published in 1904[7] by the Berlin psychiatrist and sexologist Iwan Bloch (who used a pseudonym, "Dr. Eugen Dühren", to avoid controversy).[2][6] Viscount Charles de Noailles, whose wife Marie-Laure was a direct descendant of de Sade, bought the manuscript in 1929.[8] It was inherited by their daughter Natalie, who kept it in a drawer on the family estate. She would occasionally bring it out and show it to guests, among them the writer Italo Calvino.[8] Natalie de Noailles later entrusted the manuscript to a friend, Jean Grouet. In 1982, Grouet betrayed Natalie de Noailles' trust and smuggled the manuscript into Switzerland, where he sold it to for $60,000.[8] An international legal wrangle ensued, with a French court ordering it to be returned to the Noailles family, only to be overruled in 1998 by a Swiss court that declared it had been bought by the collector in good faith.[2] She filed suit in France, and in 1990 France's highest court ordered the return of the manuscript. Switzerland had not yet signed the UNESCO convention for restitution of stolen cultural objects, so de Noailles had to take the case through the Swiss courts. The Swiss federal court sided with Nordmann, ruling in 1998 that he had bought the manuscript in good faith.[8]

It was first put on display near Geneva in 2004. Gérard Lhéritier, president and founder of Aristophil, a company specializing in rare manuscripts, bought the scroll for €7 million, and in 2014 put it on display at his Musée des Lettres et Manuscrits (Museum of Letters and Manuscripts) in Paris.[2][7][6] In 2015, Lhéritier was taken into police custody and charged with fraud for allegedly running his company as a Ponzi scheme.[9] The manuscripts were seized by French authorities and were due to be returned to their investors before going to auction.[10] On December 19, 2017, the French government recognized the original manuscript as a National Treasure. The move came just days before the manuscript was expected to be sold at auction. As a National Treasure, French law stipulates that it must be kept in France for at least 30 months, which would give the government time to raise funds to purchase it.[11][12][6] In early 2021, the French government announced that it offered tax benefits to corporations aiding it in acquiring the original manuscript for the National Library of France by sponsoring a sum of €4.55 million.[13]

Assessments[]

Sade described his work as "the most impure tale that has ever been told since the world began".[14] The first publisher of the work, Bloch, regarded its thorough categorisation of all manner of sexual fetishes as having "scientific importance ... to doctors, jurists, and anthropologists". He equated it with Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis. Feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir wrote an essay titled "Must We Burn Sade?", protesting the destruction of The 120 Days of Sodom because of the light it sheds on humanity's darkest side when, in 1955, French authorities planned on destroying it and three other major works by Sade.[15]

Camille Paglia considers Sade's work a "satirical response to Jean-Jacques Rousseau" in particular, and the Enlightenment concept of man's innate goodness in general. Gilles Deleuze considers The 120 Days along with the rest of Sade's corpus in conjunction with Leopold von Sacher-Masoch:

The work of Sade and Masoch cannot be regarded as pornography; it merits the more exalted title of 'pornology' because its erotic language cannot be reduced to the elementary functions of ordering and describing.[16]

Georges Bataille points in his Literature and Evil:

In the solitude of prison Sade was the first man to give a rational expression to those uncontrollable desires, on the basis of which consciousness has based the social structure and the very image of man… Indeed this book is the only one in which the mind of man is shown as it really is. The language of Les Cent Vingt Journées de Sodome is that of a universe which degrades gradually and systematically, which tortures and destroys the totality of the beings which it presents… Nobody, unless he is totally deaf to it, can finish Les Cent Vingt Journées de Sodome without feeling sick.’

Chronology[]

The novel is set out to a strict timetable. For each of the first four months, November to February, the prostitutes take turns to tell five stories each day, relating to the fetishes of their most interesting clients, and thus totaling 150 stories for each month (in theory at least; de Sade made a few mistakes, as he was apparently unable to go back and review his work as he went along). These passions are separated into four categories – simple, complex, criminal, and murderous – escalating in complexity and savagery.

- November: the simple passions – these anecdotes are the only ones written in detail. They are only considered 'simple' in terms of them not including actual sexual penetration. The anecdotes include men who like to masturbate in the faces of seven-year-old girls and indulge in urine drinking and coprophagia/scatology. As they do throughout the story-telling sections, the four libertines – Blangis, the Bishop, Curval and Durcet – indulge in activities similar to those they have heard with their daughters and the kidnapped children.

- December: the complex passions – these anecdotes involve more extravagant perversions, such as men who vaginally rape female children and indulge in incest and flagellation. Tales of men who indulge in sacrilegious activities are also recounted, such as a man who enjoyed having sex with nuns whilst watching Mass being performed. The female children are deflowered vaginally during the evening orgies with other elements of that month's stories – such as whipping – occasionally thrown in.

- January: the criminal passions – tales are told of perverts who indulge in criminal activities, albeit stopping short of murder. They include men who sodomise girls as young as three, men who prostitute their own daughters to other perverts and watch the proceedings and others who mutilate women by tearing off their fingers or burning them with red-hot pokers. During the month, the four libertines begin having anal sex with the sixteen male and female children who, along with the other victims, are treated more brutally as time goes on, with regular beatings and whippings.

- February: the murderous passions – the final 150 anecdotes are those involving murder. They include perverts who skin children alive, disembowel pregnant women, burn entire families alive and kill newborn babies in front of their mothers. The final tale is the only one since the simple passions of November written in detail. It features the 'Hell Libertine' who masturbates while watching 15 teenage girls being simultaneously tortured to death. During this month, the libertines brutally kill three of the four daughters they have between them, along with four of the female children and two of the male ones. The murder of one of the girls, 15-year-old Augustine, is described in great detail, with the tortures she is subjected to including having her flesh stripped from her limbs, her vagina being mutilated and her intestines being pulled out of her sliced-open belly and burned.

- March – this is the shortest of the segments, de Sade summarising things even more by this final point in the novel. He lists the days on which the surviving children and many of the other characters are disposed of, although he does not give any details. Instead he leaves a footnote to himself pointing out his intention on detailing things more in a future revision.

It is perhaps significant that de Sade was interested in the manner in which sexual fetishes are developed, as are his primary characters, who urge the storytellers to remind them, in later stages, as to what the client in that particular anecdote enjoyed doing in their younger years. There are therefore a number of recurring figures, such as a man who, in the early tales, enjoys pricking women's breasts with pins and, at his reappearance in the tales in the 'murderous passions' category, delights in killing women by raping them atop a bed of nails. At the end of the novel, de Sade draws up a list of the characters with a note of those who were killed and when, and also those who survived.

The characters consider it normal, even routine, to sexually abuse very young children, both male and female. A lot of attention is given to feces, which the men consume as a delicacy. They designate the chapel for defecation.

Film adaptations[]

In the final vignette of L'Age d'Or (1930), the surrealist film directed by Luis Buñuel and written by Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, the intertitle narration tells of an orgy of 120 days of depraved acts – a reference to The 120 Days of Sodom – and tells us that the survivors of the orgy are ready to emerge. From the door of a castle emerges the Duc de Blangis, who is supposed to look like Christ. When a young girl runs out of the castle, the Duc comforts the girl, but then escorts her back inside. A loud scream is then heard and he reemerges with blood on his robes and missing his beard.[citation needed]

In 1975, Pier Paolo Pasolini turned the book into a film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma). The film is transposed from 18th-century France to the last days of Benito Mussolini's regime in the Republic of Salò. Salò is commonly listed among the most controversial films ever made.[18]

See also[]

- Philosophy in the Bedroom, Justine, and Juliette, other works by Sade

- Sadism

References[]

- ^ Alternatively The School of Licentiousness

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Willsher, Kim (April 3, 2014). "Original Marquis de Sade scroll returns to Paris". The Guardian. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ "Sade's 120 Days of Sodom to return to France after two centuries' adventures". RFI. April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marquis de Sade (1966) [1785]. "Forward". In Seaver, Richard; Wainhouse, Austryn (eds.). 120 Days of Sodom and Other Writings. New York City: Grove Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b University of Melbourne (2013). Banned Books in Australia - A Special Collections-Art in the Library Exhibition." Retrieved on 2014-12-06 from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "The 120 Days of Sodom: France seeks help to buy 'most impure tale ever written'". the Guardian. 2021-02-22. Retrieved 2021-02-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Perrottet, Tony (February 2015). "Who Was the Marquis de Sade?". Smithsonian Magazine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sciolino, Elaine. (2013, January 22). It's a Sadistic Story, and France Wants It. The New York Times, p. C5.

- ^ Paris, Angelique Chrisafis (March 6, 2015). "France's 'king of manuscripts' held over suspected pyramid scheme fraud". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Noce, Vincent (16 March 2017). "Bankrupt French company's huge stock of precious manuscripts to go on sale". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "De Sade's 120 Days of Sodom declared French national treasure". RFI. 19 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura (19 December 2017). "Halting Auction, France Designates Marquis de Sade Manuscript a 'National Treasure'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- ^ "Avis d'appel au mécénat d'entreprise pour l'acquisition par l'Etat d'un trésor national dans le cadre de l'article 238 bis-0 A du code général des impôts - Légifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2021-02-22.

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (January 22, 2013). "It's a Sadistic Story, and France Wants It". The New York Times. New York City. p. C1. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ de Beauvoir, Simone (1999) [1955]. Sawhney, Deepak Narang (ed.). Must We Burn Sade?. Amherst, New York: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1573927390.

- ^ Deleuze, Gilles; von Sacher-Masoch, Leopold (1991). Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty & Venus in Furs. Translated by Jean McNeil. New York City: Zone Books. ISBN 978-0942299557.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books/about/Literature_and_Evil.html

- ^ Saunders, Tristram Fane (July 7, 2016). "Box-office gross: 12 movies that made audiences sick, from The Exorcist to The House that Jack Built". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

Bibliography[]

- The 120 Days of Sodom Penguin Books, London 2016 ISBN 978-0141394343

- The 120 Days of Sodom and Other Writings, Grove Press, New York; Reissue edition 1987 ISBN 978-0-8021-3012-9

External links[]

| French Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- English translation of French text. Another source for the same translation

- McLemee, Scott. "Sade, Marquis de (1740-1814)". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Novels by the Marquis de Sade

- 1785 novels

- 1904 French novels

- French LGBT novels

- 18th century in LGBT history

- Novels about French prostitution

- Obscenity controversies in literature

- Unfinished novels

- Prison writings

- Novels about child sexual abuse

- Novels about ephebophilia

- Novels about serial killers

- Novels set in Germany

- Pedophilia in literature

- French novels adapted into films

- Incest in fiction

- Novels published posthumously

- Matricide in fiction

- Sororicide in fiction

- Filicide in fiction

- Censored books

- Works about torture

- Books critical of Christianity