The Age

Front page of The Age (11 May 2020) | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Compact |

| Owner(s) | Nine Entertainment |

| Editor | Gay Alcorn |

| Founded | 17 October 1854 |

| Headquarters | Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Readership | Total 5.321 million, Digital 4.849 million, Print 1.198 million (EMMA, March 2020) |

| ISSN | 0312-6307 |

| Website | theage |

The Age is a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, that has been published since 1854. Owned and published by Nine Entertainment, The Age primarily serves Victoria, but copies also sell in Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and border regions of South Australia and southern New South Wales. It is delivered both in print and digital formats. The newspaper shares some articles with its sister newspaper The Sydney Morning Herald.

The Age is considered a newspaper of record for Australia, and has variously been known for its investigative reporting, with its journalists having won dozens of Walkley Awards, Australia's most prestigious journalism prize.[1][2] As of March 2020, The Age had a monthly readership of 5.321 million.[3]

History[]

Foundation[]

Three Melbourne businessmen, brothers John and Henry Cooke (who had arrived from New Zealand in the 1840s) and Walter Powell founded The Age. The first edition appeared on 17 October 1854.

Syme family[]

The venture was not initially a success, and in June 1856 the Cookes sold the paper to Ebenezer Syme, a Scottish-born businessman, and James McEwan, an ironmonger and founder of McEwans & Co, for 2,000 pounds at auction. The first edition under the new owners came out on 17 June 1856. From its foundation the paper was self-consciously liberal in its politics: "aiming at a wide extension of the rights of free citizenship and a full development of representative institutions", and supporting "the removal of all restrictions upon freedom of commerce, freedom of religion and—to the utmost extent that is compatible with public morality—upon freedom of personal action".[4]

Ebenezer Syme was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly shortly after buying The Age, and his brother David Syme soon came to dominate the paper, editorially and managerially. When Ebenezer died in 1860 David became editor-in-chief, a position he retained until his death in 1908, although a succession of editors did the day-to-day editorial work.

In 1882 The Age published an eight-part series written by journalist and future physician George E. Morrison, who had sailed, undercover, for the New Hebrides, while posing as crew of the brigantine slave-ship, Lavinia, as it made cargo of Kanakas. By October the series was also being published in The Age's weekly companion magazine, the Leader. "A Cruise in a Queensland Slaver. By a Medical Student" was written in a tone of wonder, expressing "only the mildest criticism"; six months later, Morrison "revised his original assessment", describing details of the schooner's blackbirding operation, and sharply denouncing the slave trade in Queensland. His articles, letters to the editor, and newspaper's editorials, led to expanded government intervention.[5]

In 1891, Syme bought out Ebenezer's heirs and McEwan's and became sole proprietor. He built up The Age into Victoria's leading newspaper. In circulation, it soon overtook its rivals The Herald and The Argus, and by 1890 it was selling 100,000 copies a day, making it one of the world's most successful newspapers.

Under Syme's control The Age exercised enormous political power in Victoria. It supported liberal politicians such as Graham Berry, George Higinbotham and George Turner, and other leading liberals such as Alfred Deakin and Charles Pearson furthered their careers as The Age journalists. Syme was originally a free trader, but converted to protectionism through his belief that Victoria needed to develop its manufacturing industries behind tariff barriers. During the 1890s The Age was a leading supporter of Australian federation and of the White Australia policy.

After David Syme's death, the paper remained in the hands of his three sons, with his eldest son Herbert becoming general manager until his death in 1939.

David Syme's will prevented the sale of any equity in the paper during his sons' lifetimes, an arrangement designed to protect family control, but which had the unintended consequence of starving the paper of investment capital for 40 years.

Under the management of Sir Geoffrey Syme (1908–42), and his editors, Gottlieb Schuler and Harold Campbell, The Age was unable to modernise, and gradually lost market share to The Argus and the tabloid The Sun News-Pictorial, with only its classified advertisement sections keeping the paper profitable. By the 1940s, the paper's circulation was lower than it had been in 1900, and its political influence had also declined. Although it remained more liberal than the extremely conservative Argus, it lost much of its distinct political identity.

The historian Sybil Nolan writes: "Accounts of The Age in these years generally suggest that the paper was second-rate, outdated in both its outlook and appearance. Walker described a newspaper which had fallen asleep in the embrace of the Liberal Party; "querulous", "doddery" and "turgid" are some of the epithets applied by other journalists. It is inevitably criticised not only for its increasing conservatism, but for its failure to keep pace with innovations in layout and editorial technique so dramatically demonstrated in papers like The Sun News-Pictorial and The Herald."

In 1942, David Syme's last surviving son, Oswald, took over the paper, and began to modernise the paper's appearance and standards of news coverage, removing classified advertisements from the front page and introducing photographs long after other papers had done so.

In 1948, after realising the paper needed outside capital, Oswald persuaded the courts to overturn his father's will and floated David Syme and Co. as a public company, selling 400,000 pounds' worth of shares. This sale enabled a badly needed technical upgrade of the newspaper's antiquated production machinery, and defeated a takeover attempt by the Fairfax family, publishers of The Sydney Morning Herald.

This new lease on life allowed The Age to recover commercially, and in 1957 it received a great boost when The Argus, after twenty years of financial losses, ceased publication.

1960–present[]

Oswald Syme retired in 1964 and his grandson Ranald Macdonald was appointed managing director at the age of 26 and Two years later he appointed Graham Perkin as editor. in order to ensure that the 36-year-old Perkin was free of board influence, Macdonald took on the role of editor-in-chief, a position he held until 1970. Together they radically changed the paper's format and shifted its editorial line from rather conservative liberalism to a new "left liberalism" characterised by attention to issues such as race, gender, the disabled and the environment, as well as opposition to White Australia and the death penalty.

It also became more supportive of the Australian Labor Party after years of having usually supported the Coalition. The Liberal Premier of Victoria, Henry Bolte, subsequently called The Age "that pinko rag" in a view conservatives have maintained ever since. Former editor Michael Gawenda in his book American Notebook wrote that the "default position of most journalists at The Age was on the political Left."[6] In 1966, the Syme family shareholders joined with Fairfax to create a 50/50 voting partnership which guaranteed editorial independence and forestalled takeover moves from newspaper proprietors in Australia and overseas. This lasted for 17 years, until Fairfax bought controlling interest in 1972.

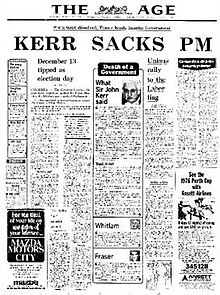

Perkin's editorship coincided with Gough Whitlam's reforms of the Labor Party, and The Age became a key supporter of the Whitlam government, which came to power in 1972. Contrary to subsequent mythology, however, The Age was not an uncritical supporter of Whitlam, and played a leading role in exposing the Loans Affair, one of the scandals which contributed to the demise of the Whitlam government. It was one of many papers to call for Whitlam's resignation on 15 October 1975. Its editorial that day, "Go now, go decently", began, "We will say it straight, and clear, and at once. The Whitlam Government has run its course." It would be Perkin's last editorial; he died the next day.

After Perkin's death, The Age returned to a more moderate liberal position. While it criticised Whitlam's dismissal later that year, it supported Malcolm Fraser's Liberal government in its early years. However, after 1980 it became increasingly critical and was a leading supporter of Bob Hawke's reforming government after 1983. But from the 1970s, the political influence of The Age, as with other broadsheet newspapers, derived less from what it said in its editorial columns (which relatively few people read) than from the opinions expressed by journalists, cartoonists, feature writers and guest columnists. The Age has always kept a stable of leading editorial cartoonists, notably Les Tanner, Bruce Petty, Ron Tandberg and Michael Leunig.

In 1983, Fairfax bought out the remaining shares in David Syme and Co., which became a subsidiary of John Fairfax and Co.[7] Macdonald was criticised by some members of the Syme family (who nevertheless accepted Fairfax's generous offer for their shares), but he argued that The Age was a natural partner for Fairfax's flagship property, The Sydney Morning Herald. He believed the greater resources of the Fairfax group would enable The Age to remain competitive. By the mid-1960s a new competitor had appeared in Rupert Murdoch's national daily The Australian, which was first published on 15 July 1964. In 1999 David Syme and Co. became The Age Company Ltd, finally ending the Syme connection.

The Age was published from offices in Collins Street until 1969, when it moved to 250 Spencer Street (hence the nickname "The Spencer Street Soviet" favoured by some critics). In 2003, The Age opened a new printing centre at Tullamarine. The Headquarters moved again in 2009 to Collins Street opposite Southern Cross station. Since acquisition by Nine, the headquarters was moved to 717 Bourke St, Docklands, Melbourne, Victoria, which is also tenanted by Nine.

In 2004, editor Michael Gawenda was succeeded as editor by British journalist Andrew Jaspan, who was in turn replaced by Andrew Holden in 2012.[8]

The Age has been known for its tradition of investigative reporting. In 1984, the newspaper reported what became known as "The Age Tapes" affair, which revealed recordings made by police of alleged corrupt dealings between organised crime figures, politicians and public officials and which sparked the Stewart Royal Commission.[9] The paper's extensive reporting on malpractice in Australia's banking sector led to a Royal Commission being announced by the Turnbull Government into the financial services industry,[10] and with The Age's journalist Adele Ferguson awarded the Gold Walkley.[11] A series of stories in The Age between 2009 and 2015 about alleged corruption involving subsidiaries of Australia's central bank, the Reserve Bank, led to Australia's first ever prosecutions of companies and businessman for foreign bribery.[12][13] In 2017, the paper's deputy editor Michael Bachelard was awarded the Gold Walkley for The Age's reports on the liberation of Mosul after the defeat of Islamic State.[14] The Age's reporting of the Unaoil international bribery scandal led to investigations by anti-corruption agencies in the UK, US, across Europe and Australia and several businessmen pleading guilty for paying bribes in nine countries over 17 years.[15]

In February 2007, The Age's editorial section argued that Australian citizen David Hicks should be released as a prisoner from Guantanamo Bay, stating that Mr Hicks was no hero and "probably downright deluded and dangerous" but the case for releasing him was just given he was being held without charge or trial.[16][17][18]

In 2009, The Age suspended its columnist Michael Backman after one of his columns condemned Israeli tourists as greedy and badly behaved, prompting criticism that he was anti-semitic. A Press Council complaint against The Age for its handling of the complaints against Backman was dismissed.[19]

In 2014 The Age put a photograph of an innocent man, Abu Bakar Alam, on the front page, mistakenly identifying him as the perpetrator of the 2014 Endeavour Hills stabbings. As part of the settlement the newspaper donated $20,000 towards building a mosque in nearby Doveton.[20]

As of 2012, three editions of The Age are printed nightly: the NAA edition, for interstate and country Victorian readers, the MEA edition, for metropolitan areas and a final late metropolitan edition.

Like its Fairfax stablemate The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age announced in early 2007 that it would be moving from a broadsheet format to the smaller Berliner size, in the footsteps of The Guardian and The Courier-Mail.[21]

In December 2016, editor-in-chief Mark Forbes was stood down from his position pending the result of a sexual harassment investigation and was replaced by Alex Lavelle, who served for four years as chief editor.[22][23]

In September 2020, it was announced that The Age's former Washington correspondent Gay Alcorn would be appointed editor of The Age, the first woman to hold the position in the paper's history.[24]

Headquarters[]

The Age's purpose-built former headquarters, named Media House, was located at 655 Collins St, Docklands, Melbourne, Victoria. After acquisition by Nine, The Age moved to 717 Bourke St, Docklands, Melbourne, Victoria to be co-located with their new owners.[25]

Masthead[]

The Age's masthead has received a number of updates since 1854. The most recent update to the design was made in 2002. The current masthead features a stylised version of the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom and "The Age" in Electra bold type. The coat of arms features the French motto Dieu et mon droit ("God and my right"). According to The Age's art director, Bill Farr: "No one knows why they picked the royal crest. But I guess we were a colony at the time, and to be seen to be linked with the Empire would be a positive thing."[citation needed] The original 1854 masthead included the Colony of Victoria crest. In 1856, that crest was removed and in 1861, the royal coat of arms was introduced. This was changed again in 1967, with the shield and decoration altered and the lion crowned. In 1971, a bold typeface was introduced and the crest shield rounded and less ornate. In 1997, the masthead was stacked and contained in a blue box (with the logo in white). In 2002, in conjunction with an overall revamp of the paper, the masthead was redesigned in its present form.[26]

Photography[]

Though Hugh Bull was appointed the newspaper's first full-time photographer as early as 1927,[27] it was comparatively late in the history of The Age that photographs were used on the front page as a matter of course,[28] but they became, especially under the editorship of Graham Perkin and his successors,[29] a vital part of its identity, with picture credits for staff photographers, and their images, often uncropped, run across several columns.

A photographer of the rival Herald Sun Jay Town distinguishes the 'house style'; "There's a big difference between the set-up, cheesy, tight and bright Herald Sun-type [photograph] and then the nice, broadsheet picture–well, back when the Age was a fantastic broadsheet that could really showcase their photographers' work."[30] This distinction was to start to break down in 1983 with the pooling of photographers across all Fairfax publications, and the paper's change in format from broadsheet to 'compact' in 2007, preceding move to online publication and subscription; 2014 saw Fairfax Media shedding 75 per cent of its photographers.[31]

In its heyday the newspaper was a significant step in the career of notable Australian news photographers and photojournalists, many of whom started as cadets.[32][33] They include:

- Hugh Bull

- Bryan Charlton

- John Lamb

- Ron Lovitt

- Bill McAuley

- Fiona McDougall

- Justin McManus

- Simon O’Dwyer

- Bruce Postle

- Michael Rayner

- Sandy Scheltema

- Jason South

- Penny Stephens

Ownership[]

This section does not cite any sources. (October 2019) |

In 1972, John Fairfax Holdings bought a majority of David Syme's shares, and in 1983 bought out all the remaining shares.[citation needed]

On 26 July 2018, Nine Entertainment Co. and Fairfax Media, the parent company of The Age, announced they agreed on terms for a merger between the two companies to become Australia's largest media company. Nine shareholders will own 51.1 per cent of the combined entity, and Fairfax shareholders will own 48.9 per cent.[34]

Printing[]

The Age was published from its office in Collins Street until 1969, when the newspaper moved to 250 Spencer Street. In July 2003, the $220 million five-storey Age Print Centre was opened at Tullamarine.[35] The Centre produced a wide range of publications for both Fairfax and commercial clients. Among its stable of daily print publications are The Age, The Australian Financial Review and the Bendigo Advertiser. The building was sold in 2014, and printing was to be transferred to "regional presses".[36]

Editorial[]

The Age believes in "economic and social progress, in liberty and justice, in equity and compassion, and openness of government. We believe the role of government is to build a strong, fair nation for future generations, and not to pander to sectional interests."[37]

Editors[]

This section does not cite any sources. (January 2021) |

| Ordinal | Editor(s) | Year appointed | Year ended | Years as editor | Owner(s) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T. L. Bright | 1854 | 1856 | 1–2 years |

|

|

| 2 | David Blair | |||||

| 3 | Ebenezer Syme | 1856 | 1860 | 3–4 years |

|

|

| 4 | 1860 | 1867 | 6–7 years | David Syme | ||

| 5 | James Harrison | 1867 | 1872 | 4–5 years | ||

| 6 | Arthur Windsor | 1872 | 1900 | 27–28 years | ||

| 7 | Gottlieb Schuler | 1900 | 1908 | 25–26 years | ||

| 1908 | 1926 | |||||

| 8 | 1926 | 1939 | 12–13 years | |||

| 9 | 1939 | 1942 | 2–3 years | |||

| 1942 | 1959 | |||||

| 10 | 1959 | 1966 | 6–7 years | |||

| 11 | Graham Perkin | 1966 | 1972 | 8–9 years | David Syme and Co. | |

| 1972 | 1975 | John Fairfax and Sons | ||||

| 12 | Les Carlyon | 1975 | 1976 | 0–1 years | ||

| 13 | 1976 | 1979 | 2–3 years | |||

| 14 | Michael Davie | 1979 | 1981 | 1–2 years | ||

| 15 | Creighton Burns | 1981 | 1987 | 7–8 years | ||

| 1987 | 1989 |

|

||||

| 16 | Mike Smith | 1989 | 1990 | 2–3 years | ||

| 1990 | 1992 |

|

||||

| 17 | Alan Kohler | 1992 | 1995 | 2–3 years | ||

| 18 | Bruce Guthrie | 1995 | 1996 | 1–2 years | ||

| 1996 | 1997 | John Fairfax Holdings | ||||

| 19 | Michael Gawenda | 1997 | 2004 | 6–7 years | ||

| 20 | Andrew Jaspan | 2004 | 2007 | 3–4 years | ||

| 2007 | 2008 | Fairfax Media | ||||

| 21 | Paul Ramadge | 2008 | 2012 | 3–4 years | ||

| 22 | 2012 | 2016 | 3–4 years | |||

| 23 | 2016 | 2016 | 0 years | |||

| 24 | 2016 | 2020 | 3–4 years |

|

||

| 25 | Gay Alcorn | 2020 | incumbent | 0–1 years | Nine Entertainment Co |

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Walkley Foundation appoints Adele Ferguson as a director". Mumbrella. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Michael Bachelard and Kate Geraghty". The Walkley Foundation. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "News media delivers record readership as news brands reach 18.2m Australians – emma data". NewsMediaWorks. 31 May 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ "The History of The Age". About us. The Age Company Ltd. 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Kroeger, Brooke (31 August 2012). Undercover Reporting: The Truth About Deception. Northwestern University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780810163515.

- ^ Overington, Caroline (21 July 2007). "Leunig off line: ex-editor". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 22 July 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Fairfax Extends Control of David Syme and Co..,The Canberra Times, Thu 15 Sep 1983". from Trove archive, the Canberra Times.

- ^ "Andrew Holden appointed Age editor". www.abc.net.au. 26 June 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ McClymont, Kate (21 July 2017). "Lionel Murphy: Nation's most enduring judicial scandal reignited after 31 years". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "The three amigos who forced the banking royal commission". www.abc.net.au. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Foundation, Walkley (13 August 2016). "Gold Walkley award winners Mario Christodoulou (L) and Adele Ferguson, at the Walkleys Awards, December 4, 2014". ABC News. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Bribery scandal results in record $21m in fines for Reserve Bank companies". www.abc.net.au. 28 November 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Letts, business reporter Stephen (28 November 2018). "How the RBA scandal unfolded". ABC News. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Fairfax Media wins 11 Walkley Awards, including the top prize for excellence in journalism". The Sydney Morning Herald. 29 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Unaoil executives admit paying multimillion-dollar bribes". The Guardian. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Let's bring David Hicks home". The Age. 12 November 2005. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ Debelle, Penelope (5 February 2007). "The image David Hicks' family hopes will set him free". The Age. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "David Hicks is no hero but the case for freeing him is just". The Age. 30 December 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Complaint against The Age dismissed". The Age. Fairfax Media. 26 April 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Trounson, Andrew (3 March 2015). "Age sorry to victim of snap slip". The Australian.

- ^ Hogan, Jesse (26 April 2007). "Fairfax flags narrower papers, job losses". The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ^ "Subscribe to The Australian". www.theaustralian.com.au. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Josh (18 June 2020). "Age editor Alex Lavelle departs less than a week after staff voiced discontent". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Bailey, Samantha (11 September 2020). "Gay Alcorn to edit The Age". The Australian. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "The Age breaks 50-years of Spencer Street". Fairfax Media. 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Johnstone, Graeme (March 2009). "Evolution of a masthead". The Age Extra (4): 4–5. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ CREATOR. "Hugh Bull - A History of Press Photography in Australia". ppia.esrc.info. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Anderson, F. (2014) "Chasing the Pictures: Press and Magazine Photography," in Media International Australia, No. 150, pp. 47-55

- ^ Matthew Ricketson, 'Life in Australia seen through lenses of genius', The Age, 24 March 2007

- ^ Town quoted in Anderson, Fay; Young, Sally, 1975-, (author.); Henningham, Nikki, (author.); EBSCOhost (2016), Shooting the picture : press photography in Australia, The Miegunyah Press, an imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited, ISBN 978-0-522-86856-2CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Rod (May 2015). "Victoria: Fairfax to cut 80 jobs in regions". Australian Newspaper History Group Newsletter. No. 82. ISSN 1443-4962.

- ^ Whelan, Kathleen (2014), Photography of the Age : newspaper photography in Australia, from glass plate negatives to digital, Brolga Publishing, ISBN 978-1-922175-66-3

- ^ Fay Anderson (2014) 'Photography' in A Companion to the Australian Media, Bridget Griffen-Foley (ed), Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, p 337-340

- ^ https://www.smh.com.au/business/companies/what-does-the-nine-fairfax-merger-mean-20181204-p50k1o.html

- ^ Johanson, Simon (19 June 2012). "Landmark printing press site to be sold". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Johnason, Simon (23 March 2013). "Fairfax puts timeline on sale of printing presses". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ "Labor's policies best reflect our values". The Age. 5 September 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

Further reading[]

- Merrill, John C. and Harold A. Fisher. The world's great dailies: profiles of fifty newspapers (1980) pp 44–50

- C. E. Sayers, David Syme, Cheshire 1965

- Don Hauser, The Printers of the Streets and Lanes of Melbourne (1837–1975) Nondescript Press, Melbourne 2006.

External links[]

- theage.com.au – The Age website

- about.theage.com.au – The Age corporate website

- inside.theage.com.au – The Age information hub

- Half a century of obscurity (Sybil Nolan on the history of The Age)

- Sir Geoffrey Syme "Sir Geoffrey Syme Journalist & Managing Editor of The Age from 1908 until 1942"

- The Age, Google news archive. —PDF files of 32,807 issues, dating from 1854 to 1989.

- The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954) at Trove

- Newspapers on Trove

- Newspapers published in Melbourne

- Publications established in 1854

- 1854 establishments in Australia

- Fairfax family (publishers)

- Australian news websites

- Fairfax Media

- Daily newspapers published in Australia

- Nine Entertainment