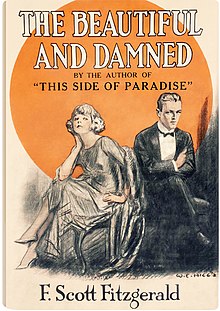

The Beautiful and Damned

First edition cover | |

| Author | F. Scott Fitzgerald |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | William E. Hill |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Published | March 4, 1922[a] |

| Publisher | Charles Scribner's Sons |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Preceded by | This Side of Paradise (1920) |

| Followed by | The Great Gatsby (1925) |

| Text | The Beautiful and Damned at Wikisource |

The Beautiful and Damned is a 1922 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, his second, that portrays New York café society and the American Eastern elite during the Jazz Age.[1] As in his other novels, Fitzgerald's characters in this novel are complex, materialistic and experience significant disruptions in respect to classism, marriage, and intimacy.

The novel purportedly was based on the early years of Fitzgerald's marriage to his wife Zelda Fitzgerald,[2] and many critics typically consider the work to be among Fitzgerald's weaker novels.[3] During the final decade of his life, Fitzgerald remarked upon the novel's lack of quality in a letter to his wife: "I wish the Beautiful and Damned had been a maturely written book because it was all true. We ruined ourselves—I have never honestly thought that we ruined each other."[4]

Plot summary[]

In 1913,[5] Anthony Patch is a twenty-five year old Harvard alumnus residing in New York City. He is the presumptive heir to his dying grandfather's vast fortune. He marries flapper Gloria Gilbert, and the couple become hedonistic libertines.

Gloria and Anthony's marital bliss soon evaporates, especially when they are each pitted against the other's selfish attitudes. Once the couple's infatuation with each other fades, they begin to see their differences that do more harm than good, as well as leaving each other with some unfulfilled hopes.

Anthony's grandfather learns of Anthony's dissipation and disinherits him. Anthony briefly serves in the United States Army during World War I and has an extramarital liaison with a Southern woman. When the battle over the grandfather's inheritance finally concludes, Anthony wins his inheritance. However, he has now become a hopeless alcoholic and his wife has lost her beauty. By the close of the novel in 1921, the couple are now wealthy but morally and physically ruined.

Major characters[]

- Anthony Patch – a self-acclaimed romantic who is an heir to his grandfather's large fortune. He is unambitious, and therefore unmotivated to work even as he pursues various careers. He is enthralled by Gloria Gilbert and falls in love with her immediately. He is drafted into the army but does not display active or patriotic service. Throughout the novel he compensates for a lack of vocation with parties and increasing alcoholism. His expectations of future wealth make him powerless to act in the present, leaving him with empty relationships in the end.

- Gloria Gilbert – a beauty who takes Anthony's heart, breaking a heart or two along the way. She is a socialite but entertains notions of becoming an actress. Gloria is self-absorbed but loves Anthony. Her personality revolves around her beauty and a belief that this makes her more important than everyone else. She simultaneously loves Anthony and hates him. Like Anthony, she is incapable of being in the present because she cannot imagine a future beyond her first flower of beauty. Gloria's obsession with her appearance spoils any chance for personal victories. The character was based on Fitzgerald's wife Zelda.[2]

- Richard "Dick" Caramel – an aspiring author and one of Anthony's best friends. During the course of the book he publishes his novel The Demon Lover and basks in his glory for a good amount of time after publication. He is Gloria's cousin and the one who brought Anthony and Gloria together.

- Mr. Bloeckman – a movie producer who is in love with Gloria and hopes she will leave Anthony for him. Gloria and Bloeckman had a relationship in the works when Gloria met Anthony. He is a friend of the family, but Gloria falls for Anthony instead. He continues to be friends with Gloria, giving Anthony some suspicion of an affair.

- Dorothy "Dot" Raycroft – the 19 year old woman that Anthony has an affair with while training for the army. She is a lost soul looking for someone to share her life with. She falls in love with Anthony despite learning that he is married, causes problems between Gloria and Anthony, and spurs Anthony's decline in mental health.

Publication history[]

Fitzgerald wrote The Beautiful and Damned quickly in the winter and spring of 1921–22 while Zelda was pregnant with their daughter.[6] He revised the work based on editorial suggestions from his friend Edmund Wilson and his editor Max Perkins.[7] The serial rights were sold to Metropolitan Magazine for $7,000, and chapters were serialized by Metropolitan from September 1921 to March 1922.[8] Finally, on March 4, 1922, the book was published. [a][9] Following his best-selling This Side of Paradise, Scribner's prepared an initial print run of approximately 20,000 copies,[10] and sold well enough to warrant additional print runs reaching 50,000 copies.[11]

Fitzgerald dedicated the novel to the Irish writer Shane Leslie, George Jean Nathan, and Maxwell Perkins "in appreciation of much literary help and encouragement".[12] Originally called by Fitzgerald The Flight of the Rocket as a working title,[5] he had divided it pre-publication into three major parts: "The Pleasant Absurdity of Things", "The Romantic Bitterness of Things", and "The Ironic Tragedy of Things".[13] As published, however, it consists of three, untitled "Books" of three chapters each:[14]

The first book tells the story of the first meeting and courtship of a beautiful and spoiled couple, Anthony and Gloria, madly in love, with Gloria ecstatically exclaiming: "mother says that two souls are sometimes created together—and in love before they're born."[15]

Book two covers the first three years of their married life together, with Anthony and Gloria vowing to adhere to:

"The magnificent attitude of not giving a damn... for what they chose to do and what consequences it brought. Not to be sorry, not to lose one cry of regret, to live according to a clear code of honor toward each other, and to seek the moment's happiness as fervently and persistently as possible."[16]

The final book recounts Anthony's disinheritance, just as the U.S. enters World War I; his year in the army while Gloria remains home alone until his return; and the couple's rapid, final decline into alcoholism, dissolution and ruin—"to the syncopated beat of the Jazz Age".

At the end, Anthony Patch shows some of the same revisionism as his grandfather in the opening chapter, describing his great wealth as a necessary consequence of his character rather than to circumstance. Fitzgerald writing in the closing lines of the novel:

"Only a few months before people had been urging him to give in, to submit to mediocrity... But he had known that he was justified in his way of life—and he had stuck it out staunchly... 'I showed them... It was a hard fight, but I didn't give up and I came through!"[17]

Critical reception[]

There is a profounder truth in The Beautiful and Damned than the author perhaps intended to convey: the hero and heroine are strange creatures without purpose or method, who give themselves up to wild debaucheries and do not, from beginning to end perform a single serious act; but you somehow get the impression that, in spite of their madness, they are the most rational people in the book.... The inference is that, in such a civilization, the sanest and most creditable thing is to forget organized society and live for the jazz of the moment.

—Edmund Wilson, Literary Spotlight, 1924[18]

With his second work, The Beautiful and Damned, Fitzgerald discarded the trappings of collegiate bildungsromans as epitomized in his preceding novel This Side of Paradise and crafted an "ironical-pessimistic" [sic] novel in the style of Thomas Hardy's oeuvre.[19] The relentless pessimism of the novel would become a point of contention with many critics.[20] Louise Field of The New York Times found the novel showed Fitzgerald to be talented but too pessimistic.[20] Likewise, critic Fanny Butcher lamented that Fitzgerald had traded the giddiness of This Side of Paradise for a sequel which plumbed "the bitter dregs of reality."[21]

With the publication of this sophomore effort, critics promptly noticed an evolution in the artistry and quality of Fitzgerald's prose.[22] Whereas This Side of Paradise had been universally castigated by critics for its lackluster prose, The Beautiful and Damned displayed greater form and construction as well as an awakened literary consciousness.[22] Paul Rosenfeld commented that certain passages easily rivaled D. H. Lawrence in their artistry.[23]

Despite this significant improvement in form and construction over This Side of Paradise, critics deemed The Beautiful and Damned to be far less ground-breaking than his debut work.[24] Fanny Butcher feared that "Fitzgerald had a brilliant future ahead of him in 1920" but, "unless he does something better... it will be behind him in 1923."[25]

Other reviewers such as John V. A. Weaver recognized that the vast improvement in literary form and construction between his first and second novels augured great prospects for Fitzgerald's future.[26] Weaver predicted that, as Fitzgerald matured into a better writer, he would become regarded as one of the greatest authors of American literature.[26] Consequently, expectations arose that Fitzgerald would significantly improve with his third work, The Great Gatsby.[27]

Authorship[]

In 1922, after the book's publication, Zelda Fitzgerald was asked by Scott's friend Burton Rascoe to review the book for the New-York Tribune as a publicity stunt.[28] Rascoe asked Zelda to pretend to review it and then to insert deliberately "a rub here and there" in order to "cause a great deal of comment."[28] Per Rascoe's wishes, Zelda jokingly titled her review "Friend Husband's Latest" and wrote in the satirical review:[29]

"It also seems to me that on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and also scraps of letters, which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home."[30]

As a consequence of this off-hand remark written in a satirical review by Zelda,[31][28] various writers such as Penelope Green have speculated that Zelda was perhaps a co-author of the novel,[32] but most Fitzgerald scholars such as Matthew J. Bruccoli stated there is no evidence whatsoever to support this claim.[33] Bruccoli states:

"Zelda does not say she collaborated on The Beautiful and Damned: only that Fitzgerald incorporated a portion of her diary 'on one page' and that he revised 'scraps' of her letters. None of Fitzgerald's surviving manuscripts shows her hand".[11]

Themes[]

The Beautiful and Damned has been described as a morality tale, a meditation on love, money and decadence, and a social documentary. It concerns the characters' disproportionate appreciation of and focus on their past, which tends to consume them in the present. The theme of absorption in the past also continues through much of Fitzgerald's later works, perhaps best summarized in the final line of his 1925 novel The Great Gatsby: "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past", which is inscribed on Fitzgerald's tombstone shared with Zelda in Maryland.[34]

According to Fitzgerald scholar James West, The Beautiful and Damned is concerned with the question of 'vocation'—what does one do with oneself when one has nothing to do?[35] Fitzgerald presents Gloria as a woman whose vocation is nothing more than to catch a husband. After her marriage to Anthony, Gloria's sole vocation is to slide into indulgence and indolence, while her husband's sole vocation is to wait for his inheritance, during which time he slides into depression and alcoholism.[36]

Adaptations[]

A film adaptation in 1922, directed by William A. Seiter, starred Kenneth Harlan as Anthony Patch and Marie Prevost as Gloria.[37] The film did well at the box office, and the critical reception was generally favorable. However, F. Scott Fitzgerald disliked the film, and he later wrote to a friend: "It's by far the worst movie I've ever seen in my life-cheap, vulgar, ill-constructed and shoddy. We were utterly ashamed of it."[38]

Translations[]

Due to the novel's popular success, there were French and German translations of the work.[39]

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ a b Mizener 1951, p. 138, states the novel was published March 3rd, whereas Bruccoli 1981, p. 163, and Tate 1998, p. 14, state the novel was published March 4th.

Citations[]

- ^ Mizener 1951, pp. 138–143; Milford 1970, pp. 86–89.

- ^ a b Milford 1970, p. 88.

- ^ Elias 1990, p. 266; Mizener 1951, pp. 138–143; Bruccoli 1981, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 155.

- ^ a b Tate 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Milford 1970, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Elias 1990, p. 254; Mizener 1951, p. 132.

- ^ Tate 1998; Bruccoli 1981.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 163; Tate 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 163.

- ^ a b Bruccoli 1981, p. 166.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. iv.

- ^ Elias 1990, p. 247.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. v.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. 131.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. 226.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. 449.

- ^ Kazin 1951, p. 83; Wilson 1952, p. 34.

- ^ Wilson 1952, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Field 1922.

- ^ Butcher 1922, p. 109.

- ^ a b Stagg 1925, p. 9; Fitzgerald 1945, p. 321.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, p. 322.

- ^ Stagg 1925, p. 9; Hammond 1922.

- ^ Butcher 1923, p. 7.

- ^ a b Weaver 1922.

- ^ Mencken 1925.

- ^ a b c Milford 1970, p. 89.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 165.

- ^ Milford 1970, p. 89; Perrill 1922, p. 15.

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 14: "The review was partly a joke".

- ^ Green 2013.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 166: "Zelda was never his collaborator".

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 218.

- ^ West 2002, pp. 48.

- ^ West 2002, pp. 48–51.

- ^ The New York Times 1922.

- ^ Tate 2007, p. 32; Ankerich 2010, p. 287.

- ^ Winters 2004, pp. 71–89.

Works cited[]

- Ankerich, Michael G. (2010). Dangerous Curves Atop Hollywood Heels: The Lives, Careers, and Misfortunes of 14 Hard-Luck Girls of the Silent Screen. BearManor. ISBN 978-1-59393-605-1.

- Butcher, Fanny (July 21, 1923). "Fitzgerald and Leacock Write Two Funny Books". Chicago Tribune (Saturday ed.). Chicago, Illinois. p. 7. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Butcher, Fanny (March 5, 1922). "Tabloid Book Review". Chicago Tribune (Sunday ed.). Chicago Illinois. p. 109. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph (1981). Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald (1st ed.). New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-183242-0 – via Internet Archive.

- Elias, Amy J. (Spring 1990). "The Composition and Revision of Fitzgerald's 'The Beautiful and Damned'". 51 (3). The Princeton University Library Chronicle: 245–66. doi:10.2307/26403800. JSTOR 26403800.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Field, Louise (March 5, 1922). "Latest Works of Fiction". The New York Times. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1922). The Beautiful and Damned. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons – via Internet Archive.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1945). Wilson, Edmund (ed.). The Crack-Up. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-0051-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Green, Penelope (April 19, 2013). "Beautiful and Damned". The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- Hammond, Percy (May 5, 1922). "Books". The New York Tribune (Friday ed.). New York City. p. 10. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kazin, Alfred, ed. (1951). F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Man and His Work (1st ed.). New York City: World Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- Mencken, H. L. (May 2, 1925). "Fitzgerald, the Stylist, Challenges Fitzgerald, the Social Historian". The Evening Sun (Saturday ed.). Baltimore, Maryland. p. 9. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Milford, Nancy (1970). Zelda: A Biography. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 1-57003-455-9 – via Internet Archive.

- Mizener, Arthur (1951). The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin – via Internet Archive.

- Perrill, Penelope (April 9, 1922). "Paris Guide Book Now Very Much Sought For". Dayton Daily News (Sunday ed.). Dayton, Ohio. p. 15. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Stagg, Hunter (April 18, 1925). Scott Fitzgerald's Latest Novel is Heralded As His Best. The Evening Sun (Saturday ed.). Baltimore, Maryland. p. 9. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tate, Mary Jo (2007). Critical Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0845-2 – via Google Books.

- Tate, Mary Jo (1998) [1997]. F. Scott Fitzgerald A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 0-8160-3150-9.

- "The Screen: A Gay Cruze". The New York Times. December 11, 1922. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- Weaver, John V. A. (March 4, 1922). Better Than 'This Side of Paradise'. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Saturday ed.). Brooklyn, New York. p. 3. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- West, James L. W. III (2002). "The Question of Vocation in This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and Damned". In Prigozy, Ruth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–56. ISBN 0-521-62447-9.

- Wilson, Edmund (1952). The Shores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the Twenties and Thirties. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Young – via Internet Archive.

- Winters, Marion (2004). "German Translations of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Beautiful and Damned. A Corpus-based Study of Modal Particles as Features of Translators' Style". In Kemble, Ian (ed.). Using Corpora and Databases in Translation: Proceedings of the Conference Held on 14th November 2003 in Portsmouth. London: University of Portsmouth. pp. 71–89. ISBN 1861373651.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Beautiful and Damned at Standard Ebooks

- The Beautiful and Damned at Project Gutenberg

- The Beautiful and Damned at Internet Archive

The Beautiful and Damned public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Beautiful and Damned public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- 1922 American novels

- Modernist novels

- Novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- American novels adapted into films

- Novels set in the Roaring Twenties

- Novels set in New York City