The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in French Polynesia

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in French Polynesia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Membership | 28,704 (2019)[1] |

| Stakes | 11 |

| Districts | 2 |

| Wards | 73 |

| Branches | 23 |

| Total Congregations | 96 |

| Missions | 1 |

| Temples | 1 |

| Family History Centers | 22[2] |

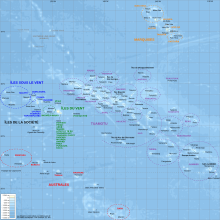

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the French Polynesia refers to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and its members in French Polynesia. The LDS Church in French Polynesia was founded in 1843 as the first foreign-language mission of the church. It existed until 1852 when it was closed due to restrictions by the French government, and the missionaries left the territory. In 1892, the mission resumed with the return of the missionaries after general religious tolerance was established.

As of 2019, there were 28,704 members in 96 congregations.[1] The French Polynesia has the third most LDS Church members per capita in Polynesia, and the fourth most members per capita of any country in the world, behind Tonga, Samoa, and Kiribati.[3]

History[]

| Year | Membership |

|---|---|

| 1846 | 866 |

| 1930 | 1,149 |

| 1940 | 1,488 |

| 1950 | 1,671 |

| 1960 | 2,920 |

| 1970 | 4,721 |

| 1980 | 6,600 |

| 1989* | 11,000 |

| 1999 | 16,230 |

| 2009 | 20,805 |

| 2019 | 28,704 |

| *1989 membership was published as a rounded number for both French Polynesia and American French Polynesia Source: Windall J. Ashton; Jim M. Wall, Deseret News, various years, Church Almanac Country Information: French Polynesia | |

Early missionary efforts: 1843 to 1852[]

On May 11, 1843, Addison Pratt, Noah Rogers, Knowlton F. Hanks, and Benjamin F. Grouard were called as missionaries[4] to the South Pacific by Joseph Smith. They were set apart by Heber C. Kimball, Brigham Young, Orson Hyde, and Parley P. Pratt on May 23,[5] and left Nauvoo, Illinois, on May 23.[6]: 3 This mission was the first foreign-language mission created by the church.[5] They set sail to the Society Islands on October 9, 1843, after being unable to find a ship to their mission area.[5] Although their destination was to the Society Islands, their provisions ran short and they stopped in Tahiti. Hanks was the first Mormon missionary to die at sea on November 3,[6]: 4 and the other missionaries spent six months on board their ship.[7]

The three missionaries arrived in Tubuai on April 30, 1844.[4] Pratt stayed alone on the island and had success during his first year. He was able to baptize 60 people in his first year there. Eventually he baptized enough people to establish a small congregation, known in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as a branch,[7] in 1844.[8] Pratt's early success may have been due to the fact that he knew some Hawaiian and was, therefore, able to recognize some cognate words between the two languages, allowing him to gain favor with natives. The first member of the church in French Polynesia was a convert that Pratt baptized, Ambrose Alexander. He was baptized on June 15, 1844; he was joined by ten more members five weeks later.[4] The missionaries not only taught principles of church teachings and doctrines, but emphasized the export of cash crops and economic autonomy.[9]: 143

Rogers and Grouard both arrived in Tahiti on May 14,[4] where they taught people on over nine islands.[7] They began teaching Europeans on the island while they were learning Tahitian. The first converts on Tahiti were Seth George Lincoln and his wife.[4] They focused their proselyting efforts mainly on crews of whaling ships. Rogers left Grouard on October 17, 1844, after hearing that there may be sailors on Huahine that would be receptive to teachings. Gourard, who felt alone after his companion left, traveled to visit Pratt in Tubuai. The two companions were reunited in Tahiti in early 1845, but decided that it was best if they sailed to different islands to spread the gospel. Rogers traveled to Mangaia and then returned to Tahiti in June because he did not find success there. Grouard visited Tuamotus, but did not find that it would be fruitful for missionary work; he went to the island of Anaa instead and landed May 1, 1945.[6]: 8–9 Rogers returned to the U.S. in 1845.[4]

Grouard became the first white missionary to live in Anaa. He baptized 620 people and organized 5 branches in the area during only 5 months. French Polynesia's first church conference was held on this island in 1846 that saw 866 members in attendance.[10] Due to the increasing number of members, Grouard sent for Pratt to come help him.[6]: 12 Pratt later joined Grouard[4] and they baptized over 1,000 people in French Polynesia before Pratt returned to Salt Lake City in 1848.[7] While in Salt Lake City with his family, Pratt taught Tahitian classes. Pratt even returned two years later with his family. his wife Louisa Barnes Pratt taught classes to the women of the church and conducted school. In October 1950, a group of 21 missionaries arrived in Tubuai including Hanks's brother.[6]: 15–17 Missionary success did not last for long, however, since France placed restrictions on religious freedom in French Polynesia that resulted in the mission closing in May 1852.[7]

Missionaries return to French Polynesia: 1892 to 1946[]

After the missionaries left French Polynesia, church members faced harassment from some government officials and members of the Catholic Church. In 1867, general religious toleration was established in Polynesia which eventually led to the return of missionaries in the territory.[6]: 21 In 1892, missionaries were able to return to the islands.[7] Joseph W. Damron and William A. Seegmiller were the missionaries who were assigned to return to the islands. They found that many of the members who had joined the church in the mid-1800s had fallen away.[4] Joseph F. Smith, counselor in the First Presidency, called James S. Brown, who was Pratt's mission companion in 1849, to be the new mission president when it reopened.[11] Brown accepted. Upon his arrival to the islands, he discovered that there were some members who had remained faithful but that many had joined the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Eventually, Brown and the missionaries who accompanied him were successful in re-baptizing many Tahitians into the LDS Church.

Missionaries in this time worked to create more branches and construct church buildings. In July 1893, Brown turned the leadership of the mission over to Joseph W. Damron. After Damron served as president, Daniel T. Miller was called and was instrumental in translating church materials into Tahitian. Under his direction [6]: 29 The Book of Mormon was translated into Tahitian and finished on July 7, 1899, and was published in 1904.[4] Miller decided to send missionaries to Moorea and the Leeward Islands of the Society Islands.[6]: 35 Missionaries had a headquarters at Tuamotu until a new mission home was opened in October 1906 in Papeete.[4] In 1907 the mission, which had been known as the Society Islands Mission, was renamed the Tahitian Mission.[12]

Church members were visited by Elder David O. McKay who was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles at the time and Hugh J. Cannon on April 11, 1921.[4] He encouraged missionaries to get the members involved, suggested that the mission have a boat for transportation, and that the missionaries stop living with members and go live with people on islands who had not yet been exposed to the church.[6]: 56 During World War II all foreign missionaries were recalled, and church members were asked to fulfill leadership positions that the foreign missionaries had held until they were able to return in June 1946.[4]

During this time period missionaries faced difficulties like the depression, World War II, a limited population, and sprawled islands. Much of their time was spent in transportation between islands and, therefore, they did not visit the people from house-to-house as is typical of Mormon missionary work. Instead, they sold mission newspapers, directed plays, held conferences, performed service, and supervised local members. Between 1920 and 1940, 12 chapels were built.[6]: 54–55

Church expansion since the mid 1900s[]

Matthew Cowley dedicated a meetinghouse and a new mission home in Papeete just four years later on January 22, 1950. Later that same year, the church purchased a two-masted schooner that was used to aid in transporting missionaries and members from the various islands in French Polynesia.[4] The boat was called Paraita which was the Tahitian name for Addison Pratt. The schooner was scheduled to take a group of members to Hawaii to visit the temple. President McKay instructed the members to cancel the trip in 1959. The boat sank a few days later and never would have made the trip.[6]: 69 In 1963, the church experienced a tragedy when a boat that was transporting members back to Maupiti crashed. 15 church members were killed.[13]

Missionaries began teaching the French-speaking population beginning in 1955. The first French-speaking branch began in October 1957.[4] The Hamilton New Zealand Temple was completed in 1958 and members of the church were able to travel there. An elementary school was built by the church in 1964 in Tahiti.[7] In 1972 the first stake was organized in French Polynesia in Tahiti by President Spencer W. Kimball,[4] and by 1983 the Papeete Tahiti Temple was finished and dedicated.[7] The stake met in the meetinghouse that had been dedicated by Cowley.[4] The church continued to grow there and Tahiti had its second stake created in 1982, followed by a third one in 1990.[7]

The church operated an LDS school that opened in 1914. It was closed during World War II and reopened in 1964. All classes were offered in French. The school was closed permanently in 1982 and the site later became the ground for the Papeete Temple. The church began offering home-study seminary in the 1970s to high school students.[6]: 80–82

Marquesas Islands[]

In 1899 the first missionaries, Edgar L. Cropper and Eli Horton, were sent to the Marquesas Islands. There was little success in proselyting efforts, so missionaries were removed in July 1904. Missionaries were sent to the islands again in 1961 and in the 1980s, but had little success again. In 1991, however, four large families were baptized in Hiva Oa. One of these new converts was Robert O'Conner, who later was called as the branch president of the Marquesas Islands. The church built its first meetinghouse on the islands in 1998.[4]

Church relations with government officials[]

Between 1932 and 1933, the government denied visas to new missionaries. The church was accused of taking too much contribution money from the islands, and the French government did not want the American influence of foreign missionaries. In 1933, however, after a new governor was appointed in French Polynesia, relations with the church improved greatly. This governor even visited Salt Lake City.[6]: 58–59

President Russell M. Nelson, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, had the opportunity to meet the territory's president along with the entire cabinet. Gordon B. Hinckley, then president of the church, was welcomed by President Gaston Flosse to visit the islands in October 1997.[4] In January 2000, Flosse, his vice president Edward Fritche, and other government officials attended a dinner that was held by the mission president at the time, Ralph T. Andersen, in the mission home. Each official was also given a copy of The Family: A Proclamation to the World.[14] When the presidency of French Polynesia held its inauguration in 2000, a choir of 400 member of the church sang at the ceremony. After attacks on 9/11, a memorial service was held in Papeete in which missionaries who were from the U.S. were invited to sing the national anthem. Afterwards, President Flosse and other officials shook hands with the missionaries.[4]

Status today[]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints reported 25,841 members in six stakes, three districts, 90 congregations (54 wards and 29 branches), one mission, and one temple in French Polynesia.[4][7] Five percent of the population of French Polynesia is recorded as being members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[15]

Missions[]

Mission presidents[]

| Mission President | Years of service |

|---|---|

| Noah Rogers | 1843–1845 |

| Addison Pratt | 1845–1847 |

| Benjamin Franklin Grouard | 1847–1850 |

| Addison Pratt | 1849–1852 |

| James Stephens Brown | 1892–1893 |

| Joseph W. Damron | 1893–1895 |

| Frank Cutler | 1895–1896 |

| Daniel Thomas Miller | 1896–1899 |

| William Henry Chamberlin Jr. | 1899–1900 |

| Joseph Y. Haight | 1899–1902 |

| Edward S. Hall | 1900–1907 |

| Franklin Julius Fullmer | 1904–1907 |

| Frank Cutler | 1907–1908 |

| William Adam Seegmiller | 1908–1911 |

| Franklin Junius Fullmer | 1911–1914 |

| Ira Hyer | 1912–1915 |

| Ernest Crabtree Rossiter | 1915–1920 |

| Leonard John McCullough | 1917–1921 |

| Leonidas Hamlin Kennard Jr. | 1920–1922 |

| Ole Bertrand Peterson | 1922–1925 |

| Herbert Brown Foulger | 1923–1926 |

| Stanley William Bird | 1923–1927 |

| Alma Gardner Burton | 1926–1929 |

| George William Burbidge | 1929–1933 |

| LeRoy R. Mallory | 1933–1937 |

| Thomas Lambert Woodbury | 1936–1938 |

| Kenneth Richard Stevens | 1938–1940[12] |

Papeete Tahiti Temple[]

On October 27, 1983, the Papeete Tahiti Temple was dedicated by First Presidency member Gordon B. Hinckley.[16] The temple was closed in 2005 for renovations, but it was rededicated by Elder L. Tom Perry and opened in November 2006.[17]

|

|

25. Papeete Tahiti Temple | ||

|

Location: |

Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia | ||

See also[]

- French Polynesia: Religion

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in France

References[]

- ^ a b "Facts and Statistics: Statistics by Country: French Polynesia", Newsroom, LDS Church, retrieved 22 July 2021

- ^ Category:French Polynesia Family History Centers, familysearch.org, retrieved 22 July 2021

- ^ The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints membership statistics

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Country information: French Polynesia". Church News. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 29 Jan 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Paulsen, Vivian (March 1995). "150 Years in Paradise". Liahona. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Britsch, R. Lanier (December 1986). Unto the islands of the sea: A history of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific. Deseret Book. pp. 1–90. ISBN 9780877477549.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hunter, Richard. "Facts and Statistics: Statistics by Country: French Polynesia". Newsroom. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saings. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ Jenson, Andres (1941). Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. p. 888. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Newbury, Colin W. (July 1980). Tahiti Nui: Change and Survival in French Polynesia, 1767–1945. Univ of Hawaii Pr. ISBN 9780824806309.

- ^ Britsch, R. Lanier. "The Church in the South Pacific - Ensign Feb. 1976 - ensign". ChurchofJesusChrist.org. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- ^ Brown, James (1960). Giant of the Lord: Life of a Pioneer. SLC UT: Bookcraft, Inc. pp. 496–503.

- ^ a b "Tahitian Mission". Early Mormon Missionaries. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ "LDS Statistics and Church Facts | Total Church Membership". Mormon Newsroom. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- ^ "French Polynesian president meets with Church leaders". Church News. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 26 Feb 2000. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ "French Polynesia". Countries and their Cultures. Advameg Inc. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ^ "More Temples Underway around the World". Ensign. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. August 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Weaver, Sarah (18 Nov 2006). "Tahitian temple, pearl of the Pacific: Elder Perry rededicates Church's renovated edifice". Church News. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

External links[]

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Pacific Area

- ComeUntoChrist.org Latter-day Saints Visitor site

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Official site

- French-Polynesian Mission History 1843–1978

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in French Polynesia

- Christianity in French Polynesia