The Common Law (1931 film)

| The Common Law | |

|---|---|

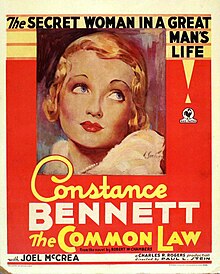

Theatrical poster of film | |

| Directed by | Paul L. Stein |

| Screenplay by | John Farrow |

| Based on | The Common Law by Robert W. Chambers |

| Produced by | Charles R. Rogers |

| Starring | Joel McCrea Constance Bennett Lew Cody |

| Cinematography | Hal Mohr |

| Edited by | Charles Craft |

| Music by | Arthur Lange |

Production company | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release dates | |

Running time | 75 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $339,000[3] |

| Box office | $713,000[3] |

The Common Law is a 1931 American pre-Code romantic drama film, directed by Paul L. Stein and produced by Charles R. Rogers. Based on Robert W. Chambers' 1911 novel of the same name, this was the third time the book was made into a film, and the first during the talking film era. The sexual drama stars Constance Bennett and Joel McCrea in the title roles. It was received well both at the box office and by film critics, becoming one of RKO's most financially successful films of the year.

Plot[]

Valerie West is a young American expatriate living with her wealthy lover, Dick Carmedon, in Paris. Tired of the relationship, she moves out, after which she meets struggling American artist John Neville. She begins posing nude for him. At first the relationship is purely business, but the two soon fall in love, and she moves in with him. The two begin to live an idyllic life, despite Carmedon's attempts to get Valerie back.

Unbeknownst to Valerie, Neville is a member of a wealthy, socially prominent family from Tarrytown, New York. Sam, a friend of Neville's, tells him about Valerie's past relationship with Carmedon. Valerie confirms it is true, but states that she left Carmedon before she met Neville. Disillusioned, Neville changes his mind about proposing to her. Valerie calls him a hypocrite and breaks up with him.

Later, Neville runs into Valerie at a nightclub, where she is out with Querido. Neville leaves in disgust. Valerie follows, jumping into his taxi and going home with him. Very soon, he proposes marriage. She asks him to wait, wanting to make sure that their feelings for one another are for real before making what she hopes will be a life-long commitment. When Clare Collins, Neville's sister, hears about the situation from friends returning from Europe, she informs Neville that their father is very ill (he only has a cough) and insists that he return home.

Neville brings Valerie with him to the family estate. Clare throws a party on the family yacht, to which she invites Carmedon and an old girlfriend of Neville's, Stephanie Brown. Neville's father tells Valerie he approves of her; he can see that his son is happy and more confident. Fed up with Clare's obvious attempts to split up the couple, Valerie turns in for the night. A drunk Carmedon barges into her stateroom, but she pushes him out, in full view of Clare. Neville helps Carmedon to his room and, behind closed doors, punches him. Then, he informs Valerie that they are going to find a justice of the peace to marry them.

Cast[]

- Constance Bennett as Valerie West

- Joel McCrea as John Neville

- Lew Cody as Dick Carmedon

- Robert Williams as Sam

- Hedda Hopper as Mrs. Clare Collis

- Marion Shilling as Stephanie Brown

- Walter Walker as John Neville, Sr.

- as Querido

- Yola d'Avril as Fifi

- Emile Chautard as Doorman (uncredited)

- Albert Conti as Strangeways Party Guest (uncredited)

- Carrie Daumery as Strangeways Party Guest (uncredited)

- George Davis as Charles - Dick's Butler (uncredited)

- Julia Swayne Gordon as Mrs. Strangeways (uncredited)

- George Irving as Doctor (uncredited)

- Dolores Murray as Queen at the Ball (uncredited)

- Tom Ricketts as Elderly Party Guest (uncredited)

- Ellinor Vanderveer as Party Guest (uncredited)

- Nella Walker as Yacht Guest (uncredited)

Production[]

Robert W. Chambers' 1911 novel was a best seller in the 1910s, and was called by some "as the most daring piece of writing that Chambers ever turned out".[4]

The novel had already been made into a film twice during the silent era, both with a Selznick producing. The first, in 1916, was produced by Lewis J. Selznick starred Clara Kimball Young and Conway Tearle. Lewis was the father of David O. Selznick. David's brother, Myron, would remake the film, this time in 1923, in which Tearle would again star, this time opposite Corinne Griffith.[5]

In February 1931, RKO announced it had purchased the rights to Chambers novel. Charles R. Rogers made the announcement, as well as stating that Constance Bennett would be the star of the film, and that John Farrow would be adapting the screenplay.[6] Production on the film was to be scheduled to begin as soon as Bennett finished shooting on Lost Love, however, due to an illness for Bennett, the start of production was delayed slightly. In mid-March, it was announced that Paul L. Stein would helm the film.[7] By the end of March, more roles were cast, with Joel McCrea, Lew Cody, Gilbert Roland, Walter Walker, Marion Shilling, and Robert Williams being assigned to the film. By this point, the only major role still to cast was that of Neville's sister, Clare.[8] The final major role would be cast in the beginning of April, with Hedda Hopper being chosen to play Clare.[9] The Common Law went into production in mid-April 1931. Gwen Wakeling, who was the head of costuming for RKO, designed the costumes.[10] Small roles would go to Erin La Bissionaire,[11] Julia Swayne Gordon,[12] Nella Walker,[13] and Yola d'Avril in the role of Fifi.[14] Margot De La Falaise, the wife of the Comte Alain De La Falaise, made her film debut in this picture, also in a small role. Alain was the younger brother of RKO's chief of French film versions, Henri.[15]

During production a yacht built for American financier, E.H. Harriman, was used as the setting for film's climactic scene.[16] One of the most expansive scenes in the film, where Neville runs into Valerie a month after she leaves him, was set at a nightclub during the famous Four Arts Ball, which was held annually in Paris. Many of the female extras in the scene had to wear full body makeup due to the scantiness of their costumes.[17] By mid-June, shooting on the film had wrapped.[18]

Williams' appearance in this film would lead to him signing on as a contract player with RKO.[19]

Marion Shilling remembered the way Bennett monopolized McCrea's time during the production. "She had a mad crush on Joel McCrea. The rest of us were just pieces of furniture to her. The minute the director yelled cut, Connie would yank Joel to her portable dressing room, bang the door and not reappear until they were again called to the set."[20]

Release[]

The film premiered at the Mayfair theater in New York on July 17, 1931; and was released nationally the following Friday, on July 24.[21] The publisher of Chambers' novel, Grosset & Dunlap, re-issued it in a special edition which featured a picture of Bennett on a wrapper; the books were prominently featured in sales displays to coincide with the film's opening.[22]

Critical response[]

The New York Age gave the film a very positive review, calling Bennett's performance, "matchless".[23] While praising the performances of Bennett and McCrae, as well as singling out the scene at the Four Arts Ball, The Film Daily gave the film a lukewarm review, stating that "... the story itself doesn't produce much of a dramatic punch due to lots of talk and little action."[2] The Reading Times gave the film a glowing review, calling Bennett "superb", and the rest of the cast "excellent".[24] Modern Screen called the film a "lavish production", and gave high marks to Bennett and the rest of the cast, stating "The star and an excellent cast imbue the old tale of artists and models with an up-to-date flavor, and the problem presented is one that will ever hold popular appeal."[25] Another favorable review was given by Motion Picture Daily, calling it a "sophisticated drama", and praising the performances of Bennett and McCrae, although they did counsel that the film was not suitable for children.[26] Photoplay also warned against bringing children to see the film, and while they lauded the performances of Bennett, McCrea, Hopper, and Cody, they did not think much of the film, calling it a "poor adaptation of Robert Chamber's best seller".[27] Screenland rated the film one of their "Six Best Pictures of the Month" in October 1931, and Bennett's performance one of the ten best.[28] Silver Screen magazine merely gave the film a "good" rating.[29]

The sexual relationships became an issue for the Hays Commission, which was in its infancy at this time in the pre-Code era, since the film promoted non-marital sex.[30]

Box office[]

According to RKO records, the film made a profit of $150,000.[3] The financial success of the film led to a new weekly record being set for RKO theaters in August 1931.[31] The Common Law was one of the few financial successes for RKO Pictures in 1931.[32]

References[]

- ^ a b "The Common Law: Detail View". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 2, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Common Law". The Film Daily. July 19, 1931. p. 10.

- ^ a b c Richard Jewel, 'RKO Film Grosses: 1931–1951', Historical Journal of Film Radio and Television, Vol 14 No 1, 1994 p39

- ^ "Constance Bennett returns to Liberty in the Greatest Triumph Since Common Clay". The Sedalia Democrat. July 26, 1931. p. 14.

- ^ "Film Article: The Common Law". Turner Classic Films. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ "Pathe Gets "Common Law" as Connie Bennett Film". The Film Daily. February 11, 1931. p. 6.

- ^ "Hollywood Activities: Connie Bennett Resuming". The Film Daily. March 15, 1931. p. 4.

- ^ "A Little from "Lots"". Silver Screen. March 30, 1931. p. 7.

- ^ "On The Dotted Line..." Motion Picture Herald. April 11, 1931. p. 60.

- ^ Wilk, Ralph (April 17, 1931). "A Little from "Lots"". The Film Daily. p. 6.

- ^ Wilk, Ralph (May 5, 1931). "A Little from "Lots"". The Film Daily. p. 6.

- ^ Wilk, Ralph (June 7, 1931). "A Little from "Lots"". The Film Daily. p. 4.

- ^ "A Little from "Lots"". The Film Daily. August 13, 1931. p. 8.

- ^ "Yola d'Avril in Common Law". The Film Daily. May 20, 1931. p. 21.

- ^ "Countess in Pathe's Common Law". The Film Daily. May 20, 1931. p. 21.

- ^ Daly, Phil M. (July 19, 1931). "Along the Rialto". The Film Daily. p. 47.

- ^ "The Common Law, Starring Constance Bennett, to Open 3-Day Run at Grand Sunday". Moberly Monitor-Index. August 15, 1931. p. 8.

- ^ "Pathe Studios Adds Four Sound Stages". The Film Daily. June 18, 1931. p. 12.

- ^ Blair, Harry N. (July 14, 1931). "Short Shots from Eastern Studios". The Film Daily. p. 6.

- ^ Ankerich, Michael G. The Sound of Silence: Conversations with 16 Film and Stage Personalities. McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC: 1998. p. 208.

- ^ "Common Law Release July 24". The Film Daily. July 15, 1931. p. 6.

- ^ "Exploitettes". The Film Daily. September 3, 1931. p. 7.

- ^ "Roosevelt Theatre". The New York Age. September 12, 1931. p. 6.

- ^ "Constance Bennett at the Capitol". Reading Times. August 19, 1931. p. 12.

- ^ "Modern Screen Reviews: The Common Law". The Modern Screen Magazine. August 1931. p. 82.

- ^ "Looking 'Em Over: 'The Common Law'". Motion Picture Daily. June 20, 1931. p. 14.

- ^ "The First and Best Talkie Reviews!". Photoplay. August 1931. p. 58.

- ^ "Reviews of the Best Pictures". Screenland. October 1931. pp. 60–61.

- ^ "Silver Screen's Reviewing Stand". Silver Screen. September 1931. p. 42.

- ^ "Riverside Common Law". The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle. July 24, 1931. p. 5.

- ^ "Current Week's Grosses in RKO Houses Sets Record". The Film Daily. August 1931. p. 4.

- ^ Jewell, Richard B.; Harbin, Vernon (1982). The RKO Story. New York: Arlington House. p. 37. ISBN 0-517-546566.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Common Law (1931 film). |

- The Common Law at IMDb

- Synopsis at AllMovie

- The Common Law at tcm.com

- 1931 films

- English-language films

- 1931 romantic drama films

- American black-and-white films

- American films

- American romantic drama films

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on works by Robert W. Chambers

- Films directed by Paul L. Stein

- Films set in Paris

- RKO Pictures films

- Films scored by Arthur Lange