The Dark Side of the Moon

| The Dark Side of the Moon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Pink Floyd | ||||

| Released | 1 March 1973 | |||

| Recorded | June 1972 – January 1973 | |||

| Studio | Abbey Road, London | |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Length | 43:09 | |||

| Label | Harvest | |||

| Producer | Pink Floyd | |||

| Pink Floyd chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Dark Side of the Moon | ||||

| ||||

The Dark Side of the Moon is the eighth studio album by the English rock band Pink Floyd, released on 1 March 1973 by Harvest Records. Primarily developed during live performances, the band premiered an early version of the record several months before recording began. The record was conceived as an album that focused on the pressures faced by the band during their arduous lifestyle, and dealing with the apparent mental health problems suffered by former band member Syd Barrett, who departed the group in 1968. New material was recorded in two sessions in 1972 and 1973 at Abbey Road Studios in London.

The record builds on ideas explored in Pink Floyd's earlier recordings and performances, while omitting the extended instrumentals that characterised their earlier work. The group employed multitrack recording, tape loops, and analogue synthesisers, including experimentation with the EMS VCS 3 and a Synthi A. Engineer Alan Parsons was responsible for many sonic aspects and the recruitment of singer Clare Torry, who appears on "The Great Gig in the Sky".

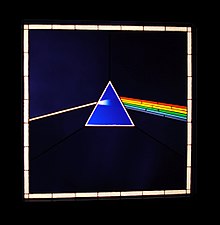

A concept album, The Dark Side of the Moon explores themes such as conflict, greed, time, death and mental illness. Snippets from interviews with the band's road crew are featured alongside philosophical quotations. The sleeve, which depicts a prism spectrum, was designed by Storm Thorgerson in response to keyboardist Richard Wright's request for a "simple and bold" design, representing the band's lighting and the album's themes. The album was promoted with two singles: "Money" and "Us and Them".

The Dark Side of the Moon is among the most critically acclaimed records in history, often featuring on professional listings of the greatest albums of all time. The record helped propel Pink Floyd to international fame, bringing wealth and recognition to all four of its members. A blockbuster release of the album era, it also propelled record sales throughout the music industry during the 1970s. It has been certified 14× platinum in the United Kingdom, and topped the US Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart, where it has charted for 958 weeks in total. With estimated sales of over 45 million copies, it is Pink Floyd's most commercially successful album, and one of the best-selling albums worldwide. In 2013, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress for being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Background[]

Following Meddle in 1971, Pink Floyd assembled for a tour of Britain, Japan and the United States in December that year. In a band meeting at drummer Nick Mason's home in Camden, bassist Roger Waters proposed that a new album could form part of the tour. Waters conceived an album that dealt with things that "make people mad", focusing on the pressures associated with the band's arduous lifestyle, and dealing with the apparent mental health problems suffered by former band member Syd Barrett.[1][2] The band had explored a similar idea with 1969's The Man and The Journey.[3] In an interview for Rolling Stone, guitarist David Gilmour said: "I think we all thought – and Roger definitely thought – that a lot of the lyrics that we had been using were a little too indirect. There was definitely a feeling that the words were going to be very clear and specific."[4]

For the most part, all four members approved of Waters' concept for an album unified by a single theme.[4] Waters, Gilmour, Mason and keyboardist Richard Wright participated in the writing and production of the new material, and Waters created the early demo tracks at his Islington home in a small studio built in his garden shed.[5] Parts of the album were taken from previously unused material; the opening line of "Breathe" came from an earlier work by Waters and Ron Geesin, written for the soundtrack of The Body,[6] and the basic structure of "Us and Them" was borrowed from an original composition by Wright for Zabriskie Point.[7] The band rehearsed at a warehouse in London owned by the Rolling Stones, and then at the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park, London. They also purchased extra equipment, which included new speakers, a PA system, a 28-track mixing desk with a four channel quadraphonic output, and a custom-built lighting rig. Nine tonnes of kit was transported in three lorries; this would be the first time the band had taken an entire album on tour.[8][9] The album had been given the provisional title of Dark Side of the Moon (an allusion to lunacy, rather than astronomy).[10] However, after discovering that title had already been used by another band, Medicine Head, it was temporarily changed to Eclipse. The new material premiered at The Dome in Brighton, on 20 January 1972,[11] and after the commercial failure of Medicine Head's album the title was changed back to the band's original preference.[12][13][nb 1]

Dark Side of the Moon: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics, as it was then known,[3] was performed in the presence of an assembled press on 17 February 1972 – more than a year before its release – at the Rainbow Theatre, and was critically acclaimed.[14] Michael Wale of The Times described the piece as "bringing tears to the eyes. It was so completely understanding and musically questioning."[15] Derek Jewell of The Sunday Times wrote "The ambition of the Floyd's artistic intention is now vast."[12] Melody Maker was less enthusiastic: "Musically, there were some great ideas, but the sound effects often left me wondering if I was in a bird-cage at London zoo."[16] The following tour was praised by the public. The new material was performed in the same order in which it was eventually sequenced on the album release; differences included the lack of synthesisers in tracks such as "On the Run", and Clare Torry's vocals on "The Great Gig in the Sky" being replaced by readings from the Bible.[14]

Pink Floyd's lengthy tour through Europe and North America gave them the opportunity to make continual improvements to the scale and quality of their performances.[17] Work on the album was interrupted in late February when the band travelled to France and recorded music for French director Barbet Schroeder's film La Vallée.[18][nb 2] They then performed in Japan and returned to France in March to complete work on the film. After a series of dates in North America, the band flew to London to begin recording, from 24 May to 25 June. More concerts in Europe and North America followed before the band returned on 9 January 1973 to complete the album.[19][20][21]

Concept[]

The Dark Side of the Moon built upon experiments Pink Floyd had attempted in their previous live shows and recordings, but it lacks the extended instrumental excursions which, according to critic David Fricke, had become characteristic of the band following founding member Syd Barrett's departure in 1968. Gilmour, Barrett's replacement, later referred to those instrumentals as "that psychedelic noodling stuff". He and Waters cited 1971's Meddle as a turning point towards what would be realised on the album. The Dark Side of the Moon's lyrical themes include conflict, greed, the passage of time, death and insanity, the latter inspired in part by Barrett's deteriorating mental state.[7] The album contains musique concrète on several tracks.[3]

Each side of the album is a continuous piece of music. The five tracks on each side reflect various stages of human life, beginning and ending with a heartbeat, exploring the nature of the human experience and, according to Waters, "empathy".[7] "Speak to Me" and "Breathe" together highlight the mundane and futile elements of life that accompany the ever-present threat of madness, and the importance of living one's own life – "Don't be afraid to care".[22] By shifting the scene to an airport, the synthesiser-driven instrumental "On the Run" evokes the stress and anxiety of modern travel, in particular Wright's fear of flying.[23] "Time" examines the manner in which its passage can control one's life and offers a stark warning to those who remain focused on mundane pursuits; it is followed by a retreat into solitude and withdrawal in "Breathe (Reprise)". The first side of the album ends with Wright and vocalist Clare Torry's soulful metaphor for death, "The Great Gig in the Sky".[3]

Opening with the sound of cash registers and loose change, the first track on side two, "Money", mocks greed and consumerism using tongue-in-cheek lyrics and cash-related sound effects. "Money" became the most commercially successful track, and has been covered by several artists in subsequent years.[24] "Us and Them" addresses the isolation of the depressed with the symbolism of conflict and the use of simple dichotomies to describe personal relationships. "Any Colour You Like" tackles the illusion of choice one has in society. "Brain Damage" looks at mental illness resulting from the elevation of fame and success above the needs of the self; in particular, the line "and if the band you're in starts playing different tunes" reflects the mental breakdown of former bandmate Syd Barrett. The album ends with "Eclipse", which espouses the concepts of alterity and unity, while forcing the listener to recognise the common traits shared by humanity.[25][26]

Recording[]

The album was recorded at Abbey Road Studios, in two sessions, between May 1972 and January 1973. The band was assigned staff engineer Alan Parsons, who had worked as assistant tape operator on its album Atom Heart Mother and gained experience as a recording engineer on the Beatles' Abbey Road and Let It Be.[27][28] The recording sessions made use of advanced studio techniques; the studio was capable of 16-track mixes, which offered a greater degree of flexibility than the eight- or four-track mixes Pink Floyd had previously used, although they often used so many tracks that to make more space available second-generation copies were made.[29]

The first track recorded was "Us and Them" on 1 June, followed six days later by "Money". Waters had created effects loops from recordings of various money-related objects, including coins thrown into a mixing bowl taken from his wife's pottery studio; these were rerecorded to take advantage of the band's decision to record a quadraphonic mix of the album. (Parsons has since expressed dissatisfaction with the result of this mix, attributed to a lack of time and the paucity of available multi-track tape recorders.)[28] "Time" and "The Great Gig in the Sky" were recorded next, followed by a two-month break, during which the band spent time with their families and prepared for an upcoming tour across the United States.[30] The recording sessions were frequently interrupted; Waters, a supporter of Arsenal F.C., would often break to see his team compete, and the band would occasionally stop work to watch Monty Python's Flying Circus on the television, leaving Parsons to work on material recorded up to that point.[29] Gilmour has, however, disputed this claim; in an interview in 2003 he said: "We would sometimes watch them but when we were on a roll, we would get on."[31][32]

On returning from the US in January 1973, they recorded "Brain Damage", "Eclipse", "Any Colour You Like" and "On the Run", while fine-tuning the work they had already laid down in the previous sessions. A group of four female vocalists was assembled to sing on "Brain Damage", "Eclipse" and "Time", and saxophonist Dick Parry was booked to play on "Us and Them" and "Money". With director Adrian Maben, the band also filmed studio footage for Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii.[33] Once the recording sessions were complete, the band began a tour of Europe.[34]

Instrumentation[]

The album features metronomic sound effects during "Speak to Me", and tape loops opening "Money". Mason created a rough version of "Speak to Me" at his home, before completing it in the studio. The track serves as an overture and contains cross-fades of elements from other pieces on the album. A piano chord, replayed backwards, serves to augment the build-up of effects, which are immediately followed by the opening of "Breathe". Mason received a rare solo composing credit for "Speak to Me".[nb 3][35][36]

The sound effects on "Money" were created by splicing together Waters' recordings of clinking coins, tearing paper, a ringing cash register, and a clicking adding machine, which were used to create a 7-beat effects loop (later adapted to four tracks to create a "walk around the room" effect in quadraphonic presentations of the album).[37] At times the degree of sonic experimentation on the album required the engineers and band to operate the mixing console's faders simultaneously, to mix down the intricately assembled multitrack recordings of several of the songs (particularly "On the Run").[7]

Along with the conventional rock band instrumentation, Pink Floyd added prominent synthesisers to their sound. For example, the band experimented with an EMS VCS 3 on "Brain Damage" and "Any Colour You Like", and a Synthi A on "Time" and "On the Run". They also devised and recorded unconventional sounds, such as an assistant engineer running around the studio's echo chamber (during "On the Run"),[38] and a specially treated bass drum made to simulate a human heartbeat (during "Speak to Me", "On the Run", "Time" and "Eclipse"). This heartbeat is most prominent as the intro and the outro to the album, but it can also be heard sporadically on "Time" and "On the Run".[7] "Time" features assorted clocks ticking, then chiming simultaneously at the start of the song, accompanied by a series of Rototoms. The recordings were initially created as a quadraphonic test by Parsons, who recorded each timepiece at an antique clock shop.[35] Although these recordings had not been created specifically for the album, elements of this material were eventually used in the track.[39]

Voices[]

Several tracks, including "Us and Them" and "Time", demonstrated Richard Wright's and David Gilmour's ability to harmonise their voices. In the 2003 Classic Albums documentary The Making of The Dark Side of the Moon, Waters attributed this to the fact that their voices sounded extremely similar. To take advantage of this, Parsons used studio techniques such as the double tracking of vocals and guitars, which allowed Gilmour to harmonise with himself. The engineer also made prominent use of flanging and phase shifting effects on vocals and instruments, odd trickery with reverb,[7] and the panning of sounds between channels (most notable in the quadraphonic mix of "On the Run", when the sound of the Hammond B3 organ played through a Leslie speaker rapidly swirls around the listener).[40]

The album's credits include Clare Torry, a session singer and songwriter, and a regular at Abbey Road. She had worked on pop material and numerous cover albums, one of which convinced Parsons to invite her to the studio to sing on Wright's composition "The Great Gig in the Sky". She declined this invitation as she wanted to watch Chuck Berry perform at the Hammersmith Odeon, but arranged to come in on the following Sunday. The band explained the concept behind the album, but were unable to tell her exactly what she should do. Gilmour was in charge of the session, and in a few short takes on a Sunday night Torry improvised a wordless melody to accompany Wright's emotive piano solo. She was initially embarrassed by her exuberance in the recording booth, and wanted to apologise to the band – only to find them delighted with her performance.[41][42] Her takes were then selectively edited to produce the version used on the track.[4] For her contribution she was paid £30,[43] her standard session fee,[40] equivalent to about £400 in 2021.[41][44] In 2004, she sued EMI and Pink Floyd for 50% of the songwriting royalties, arguing that her contribution to "The Great Gig in the Sky" was substantial enough to be considered co-authorship. The case was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum, with all post-2005 pressings crediting Wright and Torry jointly.[45][46]

Snippets of voices between and over the music are another notable feature of the album. During recording sessions, Waters recruited both the staff and the temporary occupants of the studio to answer a series of questions printed on flashcards. The interviewees were placed in front of a microphone in a darkened Studio 3,[47] and shown such questions as "What's your favourite colour?" and "What's your favourite food?", before moving on to themes more central to the album (such as madness, violence, and death). Questions such as "When was the last time you were violent?", followed immediately by "Were you in the right?", were answered in the order they were presented.[7] Roger "The Hat" Manifold proved difficult to find, and was the only contributor recorded in a conventional sit-down interview, as by then the flashcards had been mislaid. Waters asked him about a violent encounter he had had with another motorist, and Manifold replied "... give 'em a quick, short, sharp shock ..." When asked about death he responded "live for today, gone tomorrow, that's me ..."[48] Another roadie, Chris Adamson, who was on tour with Pink Floyd, recorded the snippet which opens the album: "I've been mad for fucking years – absolutely years".[49] The band's road manager Peter Watts (father of actress Naomi Watts)[50] contributed the repeated laughter during "Brain Damage" and "Speak to Me". His second wife, Patricia "Puddie" Watts (now Patricia Gleason), was responsible for the line about the "geezer" who was "cruisin' for a bruisin'" used in the segue between "Money" and "Us and Them", and the words "I never said I was frightened of dying" heard halfway through "The Great Gig in the Sky".[51]

Perhaps the most notable responses "I am not frightened of dying. Any time will do: I don't mind. Why should I be frightened of dying? There's no reason for it – you've got to go sometime" and closing words "there is no dark side in the moon, really. As a matter of fact it's all dark" came from the studios' Irish doorman, Gerry O'Driscoll.[52] Paul and Linda McCartney were also interviewed, but their answers were judged to be "trying too hard to be funny", and were not included on the album.[53] McCartney's Wings bandmate Henry McCullough contributed the line "I don't know, I was really drunk at the time".[54]

Completion[]

Following the completion of the dialogue sessions, producer Chris Thomas was hired to provide "a fresh pair of ears". Thomas's background was in music, rather than engineering. He had worked with Beatles producer George Martin, and was an acquaintance of Pink Floyd's manager, Steve O'Rourke.[55] All four members of the band were engaged in a disagreement over the style of the mix, with Waters and Mason preferring a "dry" and "clean" mix that made more use of the non-musical elements, and Gilmour and Wright preferring a subtler and more "echoey" mix.[56] Thomas later claimed there were no such disagreements, stating "There was no difference in opinion between them, I don't remember Roger once saying that he wanted less echo. In fact, there were never any hints that they were later going to fall out. It was a very creative atmosphere. A lot of fun."[57] Although the truth remains unclear, Thomas's intervention resulted in a welcome compromise between Waters and Gilmour, leaving both entirely satisfied with the end product. Thomas was responsible for significant changes to the album, including the perfect timing of the echo used on "Us and Them". He was also present for the recording of "The Great Gig in the Sky" (although Parsons was responsible for hiring Torry).[58] Interviewed in 2006, when asked if he felt his goals had been accomplished in the studio, Waters said:

When the record was finished I took a reel-to-reel copy home with me and I remember playing it for my wife then, and I remember her bursting into tears when it was finished. And I thought, "This has obviously struck a chord somewhere", and I was kinda pleased by that. You know when you've done something, certainly if you create a piece of music, you then hear it with fresh ears when you play it for somebody else. And at that point I thought to myself, "Wow, this is a pretty complete piece of work", and I had every confidence that people would respond to it.[59]

Packaging[]

It felt like the whole band were working together. It was a creative time. We were all very open.

– Richard Wright[60]

The album was originally released in a gatefold LP sleeve designed by Hipgnosis and George Hardie. Hipgnosis had designed several of the band's previous albums, with controversial results; EMI had reacted with confusion when faced with the cover designs for Atom Heart Mother and Obscured by Clouds, as they had expected to see traditional designs which included lettering and words. Designers Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell were able to ignore such criticism as they were employed by the band. For The Dark Side of the Moon, Richard Wright instructed them to come up with something "smarter, neater – more classy".[61] The design was inspired by a photograph of a prism with a colour beam projected through it that Thorgerson had found in a photography book.

The artwork was created by their associate, George Hardie. Hipgnosis offered the band a choice of seven designs, but all four members agreed that the prism was by far the best. The final design depicts a glass prism dispersing light into colour. The design represents three elements: the band's stage lighting, the album lyrics, and Wright's request for a "simple and bold" design.[7] The spectrum of light continues through to the gatefold – an idea that Waters came up with.[62] Added shortly afterwards, the gatefold design also includes a visual representation of the heartbeat sound used throughout the album, and the back of the album cover contains Thorgerson's suggestion of another prism recombining the spectrum of light, facilitating interesting layouts of the sleeve in record shops.[63] The light band emanating from the prism on the album cover has six colours, missing indigo compared to the traditional division of the spectrum into red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. Inside the sleeve were two posters and two pyramid-themed stickers. One poster bore pictures of the band in concert, overlaid with scattered letters to form PINK FLOYD, and the other an infrared photograph of the Great Pyramids of Giza, created by Powell and Thorgerson.[63]

The band were so confident of the quality of Waters' lyrics that, for the first time, they printed them on the album's sleeve.[8]

Release[]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Billboard | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B[66] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | 5/5[68] |

| NME | 8/10[69] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Sputnikmusic | 5/5[72] |

| Uncut | |

(left to right) David Gilmour, Nick Mason, Dick Parry, Roger Waters

As the quadraphonic mix of the album was not then complete, the band (with the exception of Wright) boycotted the press reception held at the London Planetarium on 27 February.[73] The guests were, instead, presented with a quartet of life-sized cardboard cut-outs of the band, and the stereo mix of the album was played over a poor-quality public address system.[74][75] Generally, however, the press were enthusiastic; Melody Maker's Roy Hollingworth described side one as "so utterly confused with itself it was difficult to follow", but praised Side Two, writing: "The songs, the sounds, the rhythms were solid and sound, Saxophone hit the air, the band rocked and rolled, and then gushed and tripped away into the night."[76] Steve Peacock of Sounds wrote: "I don't care if you've never heard a note of the Pink Floyd's music in your life, I'd unreservedly recommend everyone to The Dark Side of the Moon".[74] In his 1973 review for Rolling Stone magazine, Loyd Grossman declared Dark Side "a fine album with a textural and conceptual richness that not only invites, but demands involvement".[77] In Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), Robert Christgau found its lyrical ideas clichéd and its music pretentious, but called it a "kitsch masterpiece" that can be charming with highlights such as taped speech fragments, Parry's saxophone, and studio effects which enhance Gilmour's guitar solos.[66]

The Dark Side of the Moon was released first in the US on 1 March 1973,[78] and then in the UK on 16 March.[79] It became an instant chart success in Britain and throughout Western Europe;[74] by the following month, it had gained a gold certification in the US.[80] Throughout March 1973 the band played the album as part of their US tour, including a midnight performance at Radio City Music Hall in New York City on 17 March before an audience of 6,000. The album reached the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart's number one spot on 28 April 1973,[81] and was so successful that the band returned two months later for another tour.[82]

Label[]

Much of the album's early American success is attributed to the efforts of Pink Floyd's US record company, Capitol Records. Newly appointed chairman Bhaskar Menon set about trying to reverse the relatively poor sales of the band's 1971 studio album Meddle. Meanwhile, disenchanted with Capitol, the band and manager O'Rourke had been quietly negotiating a new contract with CBS president Clive Davis, on Columbia Records. The Dark Side of the Moon was the last album that Pink Floyd were obliged to release before formally signing a new contract. Menon's enthusiasm for the new album was such that he began a huge promotional advertising campaign, which included radio-friendly truncated versions of "Us and Them" and "Time".[83] In some countries – notably the UK – Pink Floyd had not released a single since 1968's "Point Me at the Sky", and unusually "Money" was released as a single on 7 May, with "Any Colour You Like" on the B-side.[73][nb 4] It reached number 13 on the Billboard Hot 100 in July 1973.[84][nb 5] A two-sided white label promotional version of the single, with mono and stereo mixes, was sent to radio stations. The mono side had the word "bullshit" removed from the song – leaving "bull" in its place – however, the stereo side retained the uncensored version. This was subsequently withdrawn; the replacement was sent to radio stations with a note advising disc jockeys to dispose of the first uncensored copy.[86] On 4 February 1974, a double A-side single was released with "Time" on one side, and "Us and Them" on the opposite side.[nb 6][87] Menon's efforts to secure a contract renewal with Pink Floyd were in vain however; at the beginning of 1974, the band signed for Columbia with a reported advance fee of $1M (in Britain and Europe they continued to be represented by Harvest Records).[88]

Sales[]

The Dark Side of the Moon became one of the best-selling albums of all time[89] and is in the top 25 of a list of best-selling albums in the United States.[46][90] Although it held the number one spot in the US for only a week, the album remained in the Billboard 200 albums chart for 736 nonconsecutive weeks (from 17 March 1973 to 16 July 1988).[91][92] The Dark Side of the Moon made its final appearance in the Billboard 200 albums chart during the 20th Century on the week ending 8 October 1988, in its 741st charted week.[93] The album re-appeared on the Billboard charts with the introduction of the Top Pop Catalog Albums chart in May 1991, and has been a perennial feature since then.[94] To this day, it occupies a prominent spot on Billboard's Pop Catalog chart. It reached number one when the 2003 hybrid CD/SACD edition was released and sold 800,000 copies in the US.[46] On the week of 5 May 2006 The Dark Side of the Moon achieved a combined total of 1,716 weeks on the Billboard 200 and Pop Catalog charts.[59] Upon a change in chart methodology in 2009 allowing catalogue titles to be included in the Billboard 200,[95] The Dark Side of the Moon returned to the chart at number 189 on 12 December of that year for its 742nd charting week.[96] It has continued to sporadically appear on the Billboard 200 since then, with the total at 958 weeks on the chart as of July 2021.[97] "On a slow week" between 8,000 and 9,000 copies are sold,[89] and a total of 400,000 were sold in 2002, making it the 200th-best-selling album of that year – nearly three decades after its initial release. The album has sold 9,502,000 copies in the US since 1991 when Nielsen SoundScan began tracking sales for Billboard.[98] One in every fourteen people in the US under the age of 50 is estimated to own, or to have owned, a copy.[46]

In terms of US sales certification by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), The Dark Side of the Moon was released before the introduction of platinum awards in 1976. It therefore held only a gold certification by the RIAA until 16 February 1990, when it was certified 11× platinum. On 4 June 1998, the RIAA certified the album 15× platinum,[46] denoting sales of fifteen million in the United States – making it their biggest-selling work there (The Wall is 23× platinum, but as a double album this signifies sales of 11.5 million).[99] "Money" has sold well as a single, and as with "Time", remains a radio favourite; in the US, for the year ending 20 April 2005, "Time" was played on 13,723 occasions, and "Money" on 13,731 occasions.[nb 7]

In the UK, The Dark Side of the Moon is the seventh-best-selling album of all time and the highest selling album never to reach number one.[100]

... I think that when it was finished, everyone thought it was the best thing we'd ever done to date, and everyone was very pleased with it, but there's no way that anyone felt it was five times as good as Meddle, or eight times as good as Atom Heart Mother, or the sort of figures that it has in fact sold. It was ... not only about being a good album but also about being in the right place at the right time.

– Nick Mason[75]

Industry sources suggest that worldwide sales of The Dark Side of the Moon total about 45 million.[65][101]

"The combination of words and music hit a peak," explained Gilmour. "All the music before had not had any great lyrical point to it. And this one was clear and concise. The cover was also right. I think it's become like a benevolent noose hanging behind us. Throughout our entire career, people have said we would never top the Dark Side record and tour. But The Wall earned more in dollar terms."[102] As one of the blockbuster LPs of the album era (1960s–2000s), The Dark Side of the Moon also led to an increase in record sales overall into the late 1970s.[103]

Re-issues and remastering[]

In 1979, The Dark Side of the Moon was released as a remastered LP by Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab,[104] and in April 1988 on their "Ultradisc" gold CD format.[105] The album was released by EMI and Harvest on the then-new compact disc format in Japan in June 1983,[nb 8] in the US and Europe in August 1984,[nb 9] and in 1992 it was re-released as a remastered CD in the box set Shine On.[106] This version was re-released as a 20th anniversary box set edition with postcards the following year. The cover design was again by Storm Thorgerson, the designer of the original 1973 cover.[107] On some pressings, a faintly audible orchestral version of the Beatles' "Ticket to Ride" can be heard after "Eclipse" over the album's closing heartbeats.[46]

The original quadraphonic mix,[nb 10] created by Alan Parsons,[108] was commissioned by EMI but never endorsed by Pink Floyd, as Parsons was disappointed with his mix.[28][108] To celebrate the album's 30th anniversary, an updated surround version was released in 2003. The band elected not to use Parsons' quadraphonic mix (done shortly after the original release), and instead had engineer James Guthrie create a new 5.1 channel surround sound mix on the SACD format.[28][109] Guthrie had worked with Pink Floyd since co-producing and engineering their eleventh album, The Wall, and had previously worked on surround versions of The Wall for DVD-Video and Waters' In the Flesh for SACD. Speaking in 2003, Alan Parsons expressed some disappointment with Guthrie's SACD mix, suggesting that Guthrie was "possibly a little too true to the original mix", but was generally complimentary.[28] The 30th-anniversary edition won four Surround Music Awards in 2003,[110] and has since sold more than 800,000 copies.[111] The cover image was created by a team of designers including Storm Thorgerson.[107] The image is a photograph of a custom-made stained glass window, built to match the exact dimensions and proportions of the original prism design. Transparent glass, held in place by strips of lead, was used in place of the opaque colours of the original. The idea is derived from the "sense of purity in the sound quality, being 5.1 surround sound ..." The image was created out of a desire to be "the same but different, such that the design was clearly DSotM, still the recognisable prism design, but was different and hence new".[112]

The Dark Side of the Moon was also re-released in 2003 on 180-gram virgin vinyl (mastered by Kevin Gray at AcousTech Mastering) and included slightly different versions of the posters and stickers that came with the original vinyl release, along with a new 30th anniversary poster.[113] In 2007 the album was included in Oh, by the Way, a box set celebrating the 40th anniversary of Pink Floyd,[114] and a DRM-free version was released on the iTunes Store.[111] In 2011 the album was re-released as part of the Why Pink Floyd...? campaign, featuring a remastered version of the album along with various other material.[115]

Legacy[]

It's changed me in many ways, because it's brought in a lot of money, and one feels very secure when you can sell an album for two years. But it hasn't changed my attitude to music. Even though it was so successful, it was made in the same way as all our other albums, and the only criterion we have about releasing music is whether we like it or not. It was not a deliberate attempt to make a commercial album. It just happened that way. We knew it had a lot more melody than previous Floyd albums, and there was a concept that ran all through it. The music was easier to absorb and having girls singing away added a commercial touch that none of our records had.

– Richard Wright[116]

The success of the album brought wealth to all four members of the band; Richard Wright and Roger Waters bought large country houses, and Nick Mason became a collector of upmarket cars.[117] Some of the profits were invested in the production of Monty Python and the Holy Grail.[118] Engineer Alan Parsons received a Grammy Award nomination for Best Engineered Recording, Non-Classical for The Dark Side of the Moon,[119] and he went on to have a successful career as a recording artist with the Alan Parsons Project. Although Waters and Gilmour have on occasion downplayed his contribution to the success of the album, Mason has praised his role.[120] In 2003, Parsons reflected: "I think they all felt that I managed to hang the rest of my career on Dark Side of the Moon, which has an element of truth to it. But I still wake up occasionally, frustrated about the fact that they made untold millions and a lot of the people involved in the record didn't."[32][nb 11]

Part of the legacy of The Dark Side of the Moon is its influence on modern music and on the musicians who have performed cover versions of its songs; moreover, the record gave rise to the "Dark Side of the Rainbow" theory, according to which the album matches up perfectly with the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz when they are played simultaneously. The album's release is often seen as a pivotal point in the history of rock music, and comparisons are sometimes made with Radiohead's 1997 album OK Computer,[122][123] including a premise explored by Ben Schleifer in 'Speak to Me': The Legacy of Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon (2006) that the two albums share a theme that "the creative individual loses the ability to function in the [modern] world".[124]

In a 2018 book about classic rock, Steven Hyden recalls concluding, in his teens, that The Dark Side of the Moon and Led Zeppelin IV were the two greatest albums of the genre, vision quests "encompass[ing] the twin poles of teenage desire". They had similarities, in that both album's cover and internal artwork eschew pictures of the bands in favor of "inscrutable iconography without any tangible meaning (which always seemed to give the music packaged inside more meaning)". But whereas Led Zeppelin had looked outward, toward "conquering the world" and was known at the time for its outrageous sexual antics while on tour, Pink Floyd looked inward, toward "overcoming your own hang-ups" and seemed so sedate and boring that, Hyden commented, the scene in Live at Pompeii where they take a lunch break at the studio might well have been the most interesting part of recording The Dark Side of the Moon.[125]

In 2013, The Dark Side of the Moon was selected for preservation in the United States National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress for being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[126]

Rankings[]

The Dark Side of the Moon frequently appears on professional rankings of the greatest albums.[127] In 1987, Rolling Stone ranked the record 35th in its list of the "Top 100 Albums of the Last 20 Years".[128] In 2003, the album was ranked number 43 on the magazine's list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time",[129] maintaining the ranking in a 2012 revision of the list, but dropping to number 55 in a 2020 revision of the list (the band's highest-charting album on the list).[130] Both Rolling Stone and Q have listed The Dark Side of the Moon as the best progressive rock album.[131][132]

In 2006, it was voted "My Favourite Album" by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's audience.[133] NME readers voted the album eighth in their 2006 "Best Album of All Time" online poll,[134] and in 2009, Planet Rock listeners voted the album the "greatest of all time".[135] The album is also number two on the "Definitive 200" list of albums, made by the National Association of Recording Merchandisers "in celebration of the art form of the record album".[136] It ranked 29th in The Observer's 2006 list of "The 50 Albums That Changed Music",[137] and 37th in The Guardian's 1997 list of the "100 Best Albums Ever", as voted for by a panel of artists and music critics.[138] In 2014, readers of Rhythm voted it the seventh most influential progressive drumming album.[139] It was voted number 9 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums 3rd Edition (2000).[140]

Based on such rankings, the aggregate website Acclaimed Music lists The Dark Side of the Moon as the 21st most acclaimed album in history, the seventh most acclaimed of the 1970s, and number one of albums from 1973.[127] The album's cover has also been lauded by critics and listeners alike, with VH1 proclaiming it the fourth greatest in history.[141]

Covers, tributes and samples[]

One of the more notable covers of The Dark Side of the Moon is Return to the Dark Side of the Moon: A Tribute to Pink Floyd. Released in 2006, the album is a progressive rock tribute featuring artists such as Adrian Belew, Tommy Shaw, Dweezil Zappa, and Rick Wakeman.[142] In 2000, The Squirrels released The Not So Bright Side of the Moon, which features a cover of the entire album.[143][144] The New York dub collective Easy Star All-Stars released Dub Side of the Moon in 2003[145] and Dubber Side of the Moon in 2010.[146] The group Voices on the Dark Side released the album Dark Side of the Moon a Cappella, a complete a cappella version of the album.[147] The bluegrass band Poor Man's Whiskey frequently play the album in bluegrass style, calling the suite Dark Side of the Moonshine.[148] A string quartet version of the album was released in 2003.[149] In 2009, The Flaming Lips released a track-by-track remake of the album in collaboration with Stardeath and White Dwarfs, and featuring Henry Rollins and Peaches as guest musicians.[150]

Several notable acts have covered the album live in its entirety, and a range of performers have used samples from The Dark Side of the Moon in their own material. Jam-rock band Phish performed a semi-improvised version of the entire album as part their show on 2 November 1998 in West Valley City, Utah.[151] Progressive metal band Dream Theater have twice covered the album in their live shows,[152] and in May 2011 Mary Fahl released From the Dark Side of the Moon, a song-by-song "re-imagining" of the album.[153] Milli Vanilli used the tape loops from Pink Floyd's "Money" to open their track "Money", followed by Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch on Music for the People.[154]

Dark Side of the Rainbow[]

Dark Side of the Rainbow and Dark Side of Oz are two names commonly used in reference to rumours (circulated on the Internet since at least 1994) that The Dark Side of the Moon was written as a soundtrack for the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. Observers playing the film and the album simultaneously have reported apparent synchronicities, such as Dorothy beginning to jog at the lyric "no one told you when to run" during "Time", and Dorothy balancing on a tightrope fence during the line "balanced on the biggest wave" in "Breathe".[155] David Gilmour and Nick Mason have both denied a connection between the two works, and Roger Waters has described the rumours as "amusing".[156] Alan Parsons has stated that the film was not mentioned during production of the album.[157]

Track listing[]

All lyrics are written by Roger Waters[158].

| No. | Title | Music | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Speak to Me" | Nick Mason | instrumental | 1:07 |

| 2. | "Breathe" (In the Air) |

| Gilmour | 2:49 |

| 3. | "On the Run" |

| instrumental | 3:45 |

| 4. | "Time" |

|

| 6:53 |

| 5. | "The Great Gig in the Sky" |

| Torry | 4:44 |

| 6. | "Money" | Waters | Gilmour | 6:23 |

| 7. | "Us and Them" |

| Gilmour | 7:49 |

| 8. | "Any Colour You Like" |

| instrumental | 3:26 |

| 9. | "Brain Damage" | Waters | Waters | 3:46 |

| 10. | "Eclipse" | Waters | Waters | 2:12 |

| Total length: | 43:09 | |||

Note

- Since the 2011 remasters, and the Discovery box set, "Speak to Me" and "Breathe (In the Air)" are indexed as individual tracks.

Personnel[]

Pink Floyd

- David Gilmour – vocals, guitars, Synthi AKS

- Nick Mason – drums, percussion, tape effects

- Richard Wright – organ (Hammond and Farfisa), piano, electric piano (Wurlitzer, Rhodes), EMS VCS 3, Synthi AKS, vocals

- Roger Waters – bass guitar, vocals, VCS 3, tape effects

|

Additional musicians

|

Production

Design

|

Charts[]

Weekly charts[]

|

Year-end charts[]

|

Certifications and sales[]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[254] certified in 1991 |

2× Platinum | 120,000^ |

| Argentina (CAPIF)[254] certified in 1994 |

2× Platinum | 120,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[255] video |

4× Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[256] | 14× Platinum | 980,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[257] | 2× Platinum | 100,000* |

| Belgium (BEA)[258] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[259] video |

5× Platinum | 50,000^ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[260] | 2× Diamond | 2,000,000^ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[261] Immersion Box Set |

Gold | 50,000^ |

| Czech Republic[262] | Gold | 50,000 |

| France (SNEP)[264] | Platinum | 2,084,500[263] |

| Germany (BVMI)[265] | 2× Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

| Germany (BVMI)[266] video |

Gold | 25,000^ |

| Greece | — | 45,000[267] |

| Italy sales 1977–1989 |

— | 1,000,000[268] |

| Italy (FIMI)[269] sales since 2009 |

5× Platinum | 250,000 |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[270] | 16× Platinum | 240,000^ |

| Poland (ZPAV)[271] Warner Music PL Edition |

Platinum | 100,000 |

| Poland (ZPAV)[272] Pomatom EMI edition |

Platinum | 100,000* |

| Portugal (AFP)[273] reissue |

Silver | 10,000^ |

| Russia (NFPF)[274] Remastered |

Platinum | 20,000* |

| Spain | — | 50,000[275] |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[276] video |

Platinum | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[278] | 14× Platinum | 4,300,000[277] |

| United States (RIAA)[279] video |

3× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[280] certified sales 1973–1998 |

15× Platinum | 15,000,000^ |

| United States Nielsen sales 1991–2008 |

— | 8,360,000[281] |

| Summaries | ||

| Worldwide | — | 45,000,000[65] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Release history[]

| Country | Date | Label | Format | Catalogue no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1 March 1973 | Harvest Records | Vinyl, Cassette, 8-Track | SMAS-11163 (LP) 4XW-11163 (CC) 8XW-11163 (8-Track) |

| United States | Capitol Records | |||

| United Kingdom | 16 March 1973 | Harvest Records | SHVL 804 (LP) TC-SHVL 804 (CC) Q8-SHVL 804 (8-Track) | |

| Australia | 1973 | Vinyl | Q4 SHVLA.804 |

References[]

Informational notes[]

- ^ "At one time, it was called Eclipse because Medicine Head did an album called Dark Side of the Moon. But that didn't sell well, so what the hell. I was against Eclipse and we felt a bit annoyed because we had already thought of the title before Medicine Head came out. Not annoyed at them but because we wanted to use the title." – David Gilmour[13]

- ^ This material was later released under the title Obscured by Clouds.[14]

- ^ Mason is responsible for most of the sound effects used on Pink Floyd's discography.

- ^ Harvest / Capitol 3609

- ^ According to Paul McCartney in a 1975 interview, Capitol executive Al Coury suggested that the band issue the single. McCartney recalled: "Al Coury, Capitol's ace plugger, rang up and told us 'I persuaded Pink Floyd to take "Money" off Dark Side of the Moon as a single, and you want to know how many units we sold?'"[85]

- ^ Harvest / Capitol 3832

- ^ According to Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems[89]

- ^ EMI/Harvest CP35-3017

- ^ Harvest CDP 7 46001 2

- ^ Harvest Q4SHVL-804

- ^ Alan Parsons was paid a weekly wage of £35 while working on the original album (equivalent to £500 in 2019[44]).[121]

- ^ All post-2005 pressings including "The Great Gig in the Sky" credit both Wright and Torry for the song, as per her successful court challenge.[40]

Citations[]

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 165

- ^ Harris, John (12 March 2003), 'Dark Side' at 30: Roger Waters, rollingstone.com, archived from the original on 26 March 2009, retrieved 8 June 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mabbett 1995, p. n/a

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Harris, John (12 March 2003), 'Dark Side' at 30: David Gilmour, archived from the original on 19 September 2007, retrieved 31 May 2010

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 166

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 73–74

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Classic Albums: The Making of The Dark Side of the Moon (DVD), Eagle Rock Entertainment, 26 August 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mason 2005, p. 167

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 85–86

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 159

- ^ Reising 2005, p. 28

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schaffner 1991, p. 162

- ^ Jump up to: a b Povey 2007, p. 154

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Povey 2007, pp. 154–155

- ^ Wale, Michael (18 February 1972), Pink Floyd —The Rainbow, Issue 58405; col F, infotrac.galegroup.com, p. 10, retrieved 21 March 2009

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 91–93

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 159

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 168

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 157

- ^ Povey 2007, pp. 164–173

- ^ Reising 2005, p. 60

- ^ Whiteley 1992, pp. 105–106

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 78–79

- ^ Whiteley 1992, p. 111

- ^ Reising 2005, pp. 181–184

- ^ Whiteley 1992, p. 116

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 171

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Richardson, Ken (May 2003), Another Phase of the Moon, Sound & Vision, p. 1, retrieved 20 March 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris 2006, pp. 101–102

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 103–108

- ^ Waldon, Steve (24 June 2003), There is no dark side of the moon, really ..., The Age, retrieved 19 March 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris, John (12 March 2003), 'Dark Side' at 30: Alan Parsons, archived from the original on 24 June 2008, retrieved 31 May 2010

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 158

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 109–114

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schaffner 1991, p. 164

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 172

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 104–105

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 118–120

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 173

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Povey 2007, p. 161

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blake 2008, pp. 198–199

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 174

- ^ Simpson, Dave (21 October 2014). "The little-known musicians behind some of music's most famous moments". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Ann Harrison (3 July 2014). Music: The Business (6th ed.). Random House. p. 350. ISBN 9780753550717.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Povey 2007, p. 345

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 175

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 165

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 133

- ^ Sams, Christine (23 February 2004), How Naomi told her mum about Oscar, The Sydney Morning Herald, retrieved 17 March 2009

- ^ Sutcliffe, Phil; Henderson, Peter (March 1998). "The True Story of Dark Side of the Moon". Mojo. No. 52.

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 127–134

- ^ Mark Blake (28 October 2008). "10 things you probably didn't know about Pink Floyd". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ Price, Stephen (27 August 2006). "Rock: Henry McCullough". The Times. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 177

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 178

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 135

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 134–140

- ^ Jump up to: a b Waddell, Ray (5 May 2006). "Roger Waters Revisits The 'Dark Side'". Billboard. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 3

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 143

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 165–166

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris 2006, pp. 141–147

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Review: The Dark Side of the Moon". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Smirke, Richard (16 March 2013). "Pink Floyd, 'The Dark Side of the Moon' At 40: Classic Track-By-Track Review". Billboard. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Christgau 1981, p. 303.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Pink Floyd". Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Omnibus Press. p. 1985. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Graff & Durchholz 1999, p. 874.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Dark Side of the Moon Review". Tower Records. 20 March 1993. p. 33. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Davis, Johnny (October 1994), The Dark Side of the Moon Review, Q, p. 137

- ^ Coleman 1992, p. 545.

- ^ Campbell, Hernan M. (5 March 2012), Review: Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon, Sputnikmusic, retrieved 22 October 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b Povey 2007, p. 175

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Schaffner 1991, p. 166

- ^ Jump up to: a b Povey 2007, p. 160

- ^ Hollingworth, Roy (1973), Historical info – 1973 review, Melody Maker, pinkfloyd.com, archived from the original on 28 February 2009, retrieved 30 March 2009

- ^ Grossman, Lloyd (24 May 1973). "Dark Side of the Moon Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ "[Advertisement]". Billboard. Vol. 85 no. 8. 24 February 1973. p. 1. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

Album available March 1. Tour begins March 5.

- ^ "EMI Offers Special Deal to Dealers". Billboard. Vol. 85 no. 12. London. 24 March 1973. p. 54. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

EMI is to offer stock on a sale-or-return basis to selected dealers taking part in a $50,000 campaign on four albums released March 16. ... The four albums are: Pink Floyd's "Dark Side of the Moon", ...

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 187

- ^ "Top LP's & Tape" Billboard 28 April 1973:58

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 166–167

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 158–161

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. "Money". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ Gambaccini, Paul (1996). "The McCartney Interviews: After the Break-up". p. 105.

- ^ Neely, Tim (1999), Goldmine Price Guide to 45 RPM Records (2 ed.)

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 346

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 173

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Werde, Bill (13 May 2006). "Floydian Theory". Billboard. Vol. 118 no. 19. p. 12. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums". RIAA. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Pink Floyd Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael. "The Day 'The Dark Side of the Moon' Ended Its Record Chart Run". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Billboard Top Pop Albums" (PDF). Billboard. 100 (41): 81. 1988. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Basham, David (15 November 2001). "Got Charts? Britney, Linkin Park Give Peers A Run For Their Sales Figures". MTV. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ "Seems Like Old Times: Catalog Returns To 200". Billboard. 5 December 2009.

- ^ "The Hot Box". Billboard. Vol. 121 no. 49. 12 December 2009. p. 33. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Billboard 200)". Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Grein, Paul (1 May 2013), Week Ending April 28, 2013. Albums: Snoop Lamb Is More Like It, music.yahoo.com, archived from the original on 4 November 2013, retrieved 9 July 2013

- ^ Ruhlmann 2004, p. 175

- ^ "The UK's 60 official biggest selling albums of all time revealed". Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Booth, Robert (11 March 2010), "Pink Floyd score victory for the concept album in court battle over ringtones", The Guardian, London, retrieved 22 June 2016

- ^ Gwyther, Matthew (7 March 1993). "The dark side of success". Observer magazine. p. 37.

- ^ Hogan, Marc (20 March 2017). "Exit Music: How Radiohead's OK Computer Destroyed the Art-Pop Album in Order to Save It". Pitchfork. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "MFSL Out of Print Archive – Original Master Recording LP". MOFI. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "MFSL Out of Print Archive – Ultradisc II Gold CD". MOFI. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 353

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Dark Side of the Moon – SACD re-issue, pinkfloyd.co.uk, archived from the original on 18 March 2009, retrieved 12 August 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson, Dave (9 August 2008). "The Many Sides of "Dark Side of the Moon"". Goldmine. Vol. 34 no. 18. Iola, WI: Krause Publications. pp. 38–41. ISSN 1055-2685. ProQuest 1506040.

- ^ Richardson, Ken (19 May 2003). "Tales from the Dark Side". Sound & Vision. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ^ Surround Music Awards 2003, surroundpro.com, 11 December 2003, archived from the original on 5 May 2008, retrieved 19 March 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b Musil, Steven (1 July 2007), 'Dark Side of the Moon' shines on iTunes, news.cnet.com, retrieved 12 August 2009

- ^ Thorgerson, Storm, "Album cover evolution – Storm Thorgerson explains", Pink Floyd official website, retrieved 18 August 2015 – via Brain Damage

- ^ Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon – 180 Gram Vinyl LP, store.acousticsounds.com, retrieved 29 March 2009

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (25 October 2007). ""Oh by the Way": Pink Floyd Celebrate Belated 40th Anniversary With Mega Box Set". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Why Pink Floyd?, whypinkfloyd.com, retrieved 6 July 2012

- ^ Dallas 1987, pp. 107–108

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 164–166

- ^ Parker & O'Shea 2006, pp. 50–51

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 163

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 173–174

- ^ "Inlay notes on The Alan Parsons Project", Tales of Mystery and Imagination

- ^ Griffiths 2004, p. 109

- ^ Buckley 2003, p. 843

- ^ Reising 2005, pp. 210

- ^ Hyden, Steven (2018). Twilight of the Gods: A Journey to the End of Classic Rock. Dey Street. pp. 25–27. ISBN 9780062657121.

- ^ "Chubby Checker Pink Floyd And Ramones Inducted into National Recording Registry", VNN music, 22 March 2013, retrieved 22 March 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Reising 2005, p. 7

- ^ The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, rollingstone.com, 18 November 2003, retrieved 31 May 2010

- ^ 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: Pink Floyd, 'The Dark Side of the Moon', rollingstone.com, 31 May 2012, retrieved 12 June 2012

- ^ Fischer, Reed (17 June 2015). "50 Greatest Prog Rock Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan (27 July 2010). "A-Z of progressive rock". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ My Favourite Album, abc.net.au, archived from the original on 5 December 2006, retrieved 22 March 2009

- ^ Best album of all time revealed, nme.com, 2 June 2006, retrieved 22 November 2009

- ^ Greatest Album poll top 40, planetrock.com, 2009, archived from the original on 4 October 2011, retrieved 20 March 2012

- ^ "Definitive 200", rockhall.com, rockhall.com, archived from the original on 1 August 2008, retrieved 21 June 2010

- ^ The 50 albums that changed music, guardian.co.uk, 16 July 2006, retrieved 22 November 2009

- ^ Sweeting, Adam (19 September 1997), Ton of Joy (Registration required), archive.guardian.co.uk, p. 28

- ^ Mackinnon, Eric (3 October 2014), "Peart named most influential prog drummer", Louder, retrieved 21 August 2015

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 37. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ The Greatest: 50 Greatest Album Covers, vh1.com, archived from the original on 12 November 2007, retrieved 17 March 2009

- ^ Prato, Greg, Return to the Dark Side of the Moon: A Tribute to Pink Floyd, allmusic.com, retrieved 22 August 2009

- ^ Reising 2005, pp. 198–199

- ^ The Not So Bright Side of the Moon, thesquirrels.com, archived from the original on 3 July 2008, retrieved 27 March 2009

- ^ Dub Side of the Moon, easystar.com, archived from the original on 6 February 2009, retrieved 27 March 2009

- ^ Jeffries, David (25 October 2010), Dubber Side of the Moon – Easy Star All-Stars, AllMusic, retrieved 11 December 2012

- ^ The Dark Side of the Moon – A Cappella, darksidevoices.com, archived from the original on 27 June 2013, retrieved 27 March 2009

- ^ Dark Side of the Moonshine, poormanswhiskey.com, 8 May 2007, archived from the original on 5 July 2008, retrieved 28 March 2009

- ^ The String Quartet Tribute to Pink Floyd's the Dark Side of the Moon, billboard.com, 2004, retrieved 2 August 2009

- ^ Lynch, Joseph Brannigan (31 December 2009), Flaming Lips cover Pink Floyd's 'Dark Side of the Moon' album; results are surprisingly awful, music-mix.ew.com, retrieved 14 January 2010

- ^ Iwasaki, Scott (3 November 1998), 'Phish Phans' jam to tunes by Pink 'Phloyd', deseretnews.com, retrieved 20 March 2012

- ^ Dark Side of the Moon CD, ytsejamrecords.com, retrieved 28 March 2009

- ^ Interview: Mary Fahl, nippertown.com, 22 September 2010, retrieved 11 May 2011

- ^ Reising 2005, pp. 189–190

- ^ Reising 2005, p. 57

- ^ Reising 2005, p. 59

- ^ Reising 2005, p. 70

- ^ "The Dark Side of the Moon". Harvest Records. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Kent, David (1993), Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (Illustrated ed.), St. Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book, p. 233, ISBN 0-646-11917-6

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Austriancharts.at – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 4816". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Norwegian charts portal (17/1973)". norwegiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Australian charts portal (09/05/1993)". australiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 1775". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "New Zealand charts portal (18/04/1993)". charts.nz. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Swedishcharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "GFK Chart-Track Albums: Week 15, 2003". Chart-Track. IRMA. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Italian charts portal (17/04/2003)". italiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd: The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "GFK Chart-Track Albums: Week 33, 2006". Chart-Track. IRMA. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Spanishcharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Australian chart portal (09/10/2011)". australiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon – Experience Edition" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon – Experience Edition" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Czech Albums – Top 100". ČNS IFPI. Note: On the chart page, select 201139 on the field besides the word "Zobrazit", and then click over the word to retrieve the correct chart data. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Danish charts portal (07/10/2011)". danishcharts.dk. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Finnish charts portal (40/2011)". finnishcharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon – Experience Edition". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "GFK Chart-Track Albums: Week 39, 2011". Chart-Track. IRMA. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Italian charts portal (06/10/2011)". italiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "New Zealand charts portal (03/10/2011)". charts.nz. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon – Experience Edition". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Portuguese charts portal (40/2011)". portuguesecharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Spanish charts portal (02/11/2011)". spanishcharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "South Korea Gaon Album Chart". On the page, select "2011.09.25" to obtain the corresponding chart. Gaon Chart Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "South Korea Gaon International Album Chart". On the page, select "2011.09.25", then "국외", to obtain the corresponding chart. Gaon Chart Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "Swedish charts portal (07/10/2011)". swedishcharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 1973". austriancharts.at. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1973". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1973". Billboard. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1974". Billboard. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1975". Billboard. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1980". Billboard. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1982". Billboard. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1983". Billboard. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "The Official UK Albums Chart 2003" (PDF). UKChartsPlus. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "ChartsPlusYE2005" (PDF). Chartsplus. Official Charts Company. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Classifica Annuale 2006" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on 12 January 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2021. Click on "Scarica l'allegato" to download the zipped file containing the year-end chart files.

- ^ "2006 UK Albums Chart" (PDF). ChartsPlus. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "FIMI Mercato 2009" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Classifiche annuali dei dischi più venditi e dei singoli più scaricati nel 2010" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. 17 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Classifiche annuali Fimi-GfK: Vasco Rossi con "Vivere o Niente" e' stato l'album piu' venduto nel 2011" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. 16 January 2012. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2021. Click on "Scarica allegato" to download the zipped file containing the year-end chart files.

- ^ "End Of Year Chart 2011" (PDF). Official Charts Company. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2012". Billboard. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2014". Billboard. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2015". Billboard. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2017". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2017". Billboard. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "TOP AFP 2018" (PDF). Associação Fonográfica Portuguesa (in Portuguese). Audiogest. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2018". Billboard. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2019". Ultratop. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 2019". Ultratop. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2019". Billboard. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2020". Ultratop. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 2020". Ultratop. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "Összesített album- és válogatáslemez-lista - eladási darabszám alapján - 2020" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Top Of The Music 2020: 'Persona' Di Marracash È L'album Piú Venduto" (Download the attachment and open the albums file) (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. 7 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2020". Billboard. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Argentinian album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". CAPIF. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2008 DVDs" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2007 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "Austrian album certifications – Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon" (in German). IFPI Austria. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 2008". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Canadian video certifications – Pink Floyd – The Making Of The Dark Side of the Moon". Music Canada. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Music Canada. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon – Immersion Box Set". Music Canada. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Czech Gold". Billboard. 17 November 1979. p. 70. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "InfoDisc: Les Meilleures Ventes de CD / Albums "Tout Temps"" (in French). infodisc.fr. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ "French album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in French). InfoDisc. Retrieved 8 March 2017. Select PINK FLOYD and click OK.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Pink Floyd; 'Dark Side of the Moon')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Pink Floyd; 'Dark Side of the Moon')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ "From the Music Capitols of the World – Athens" (PDF). Billboard. 18 November 1978. p. 73. Retrieved 28 October 2020 – via World Radio History.

- ^ Caroli, Daniele (9 December 1989). "Italy | Talent Challenges" (PDF). Billboard Magazine. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 101 (49): I-8. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved 25 July 2020 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 27 January 2020. Select "2020" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Select "The Dark Side of the Moon" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "Platinum CD – Archive". ZPAV. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Wyróżnienia - Platynowe płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 2003 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Top 30 Artistas". Clix Música (in Portuguese). Associação Fonográfica Portuguesa. Archived from the original on 3 July 2003. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "Russian album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon" (in Russian). National Federation of Phonogram Producers (NFPF). Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "International – Supertramp $$" (PDF). Billboard. 26 April 1980. p. 57. Retrieved 28 October 2020 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "British video certifications – Pink Floyd – The Making Of The Dark Side of the Moon". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 16 March 2020.Select videos in the Format field. Select Platinum in the Certification field. Type The Making Of The Dark Side of the Moon in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ^ Gumble, Daniel (5 July 2016). "UK's 60 Biggest Selling Albums of All Time". Music Week. Intent Media. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "British album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "American video certifications – Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "American album certifications – Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Barnes, Ken (16 February 2007). "Sales questions: Pink Floyd". USA Today. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

Bibliography[]

- Blake, Mark (2008), Comfortably Numb—The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Da Capo, ISBN 978-0-306-81752-6

- Buckley, Peter (2003), The Rough Guide to Rock, Rough Guides, ISBN 1-84353-105-4

- Christgau, Robert (1981), "Pink Floyd: The Dark Side of the Moon", Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies, Ticknor & Fields, ISBN 0-89919-025-1 – via robertchristgau.com

- Coleman, Mark (1992). "Pink Floyd". In DeCurtis, Anthony; Henke, James; George-Warren, Holly (eds.). The Rolling Stone Album Guide (3rd ed.). Random House. ISBN 0-679-73729-4.

- Dallas, Karl (1987), Pink Floyd: Bricks in the Wall, Shapolsky Publishers/Baton Press, ISBN 0-933503-88-1

- Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (eds) (1999), MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide, Farmington Hills, Michigan: Visible Ink Press, ISBN 1-57859-061-2CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Griffiths, Dai (2004), OK Computer, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0-8264-1663-2

- Harris, John (2006), The Dark Side of the Moon (third ed.), Harper Perennial, ISBN 978-0-00-779090-6

- Mabbett, Andy (1995), The Complete Guide to the Music of Pink Floyd, Omnibus Press, ISBN 0-7119-4301-X

- Mason, Nick (2005), Philip Dodd (ed.), Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (Paperback ed.), Phoenix, ISBN 0-7538-1906-6

- Parker, Alan; O'Shea, Mick (2006), And Now for Something Completely Digital, The Disinformation Company, ISBN 1-932857-31-1

- Povey, Glenn (2007), Echoes, Mind Head Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5

- Reising, Russell (2005), Speak to Me, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd, ISBN 0-7546-4019-1

- Ruhlmann, William (2004), Breaking Records, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-94305-1

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1991), Saucerful of Secrets (first ed.), London: Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN 0-283-06127-8

- Whiteley, Sheila (1992), The Space Between the Notes, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-06816-9

External links[]

Quotations related to The Dark Side of the Moon at Wikiquote

Quotations related to The Dark Side of the Moon at Wikiquote- The Dark Side of the Moon at Discogs (list of releases)

- 1973 albums

- Albums produced by David Gilmour

- Albums produced by Nick Mason

- Albums produced by Richard Wright (musician)

- Albums produced by Roger Waters

- Albums with cover art by Hipgnosis

- Albums with cover art by Storm Thorgerson

- Capitol Records albums

- Science fiction concept albums

- Works about the Moon

- EMI Records albums

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- Harvest Records albums

- Pink Floyd albums

- United States National Recording Registry recordings

- United States National Recording Registry albums