The Lion King (video game)

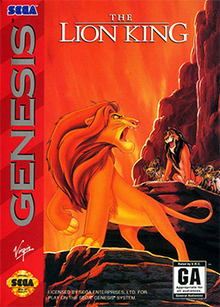

| The Lion King | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) |

|

| Publisher(s) | Virgin Interactive Entertainment |

| Director(s) | Louis Castle |

| Producer(s) | Louis Castle Patrick Gilmore Paul Curasi |

| Designer(s) | Seth Mendelsohn |

| Programmer(s) | Rob Povey Barry Green |

| Artist(s) | John Fiorito Alex Schaeffer Christina Vann Ann-Bettina Colace |

| Composer(s) | Super NES Frank Klepacki Dwight Okahara John Wright Zack Bremner Patrick Collins Genesis Matt Furniss MS-DOS, Amiga Allister Brimble Game Boy, NES Kevin Bateson |

| Series | The Lion King |

| Platform(s) | Super NES, Genesis, MS-DOS, Amiga, Game Gear, Master System, Game Boy, NES |

| Release | show

1994 |

| Genre(s) | Platform |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The Lion King is a platform game based on Disney's animated film of the same name. The game was developed by Westwood Studios and published by Virgin Interactive Entertainment for the Super NES and Genesis in 1994, and was also ported to MS-DOS, Amiga, Game Gear, Master System, and Nintendo Entertainment System. The Amiga, Master System, and NES versions were only released in the PAL region, with the NES version in particular being the last game released for the platform in the region in addition to being the final licensed game for the platform worldwide. The game follows Simba's journey from a young cub to the battle with his evil uncle Scar as an adult.

Gameplay[]

The Lion King is a side-scrolling platform game in which players control the protagonist, Simba, through the events of the film, going through both child and adult forms as the game progresses. In the first half of the game, players control Simba as a cub, who primarily defeats enemies by jumping on them. Simba also has the ability to roar, using up a replenishable meter, which can be used to stun enemies, make them vulnerable, or solve puzzles. In the second half of the game, Simba becomes an adult and gains access to various combat moves such as scratching, mauling, and throws. In either form, Simba will lose a life if he runs out of health or encounters an instant-death obstacle, such as a bottomless pit or a rolling boulder.

Throughout the game, the player can collect various types of bugs to help them through the game. Some bugs restore Simba's health and roar meters, other more rare bugs can increase these meters for the remainder of the game, while black spiders will cause Simba to lose health. By finding certain bugs hidden in certain levels, the player can participate in bonus levels in which they play as Timon and Pumbaa to earn extra lives and continues. Pumbaa's stages have him collecting falling bugs and items until either one hits the bottom of the screen or he eats a bad bug, while Timon's stages have him hunting for bugs within a time limit while avoiding spiders.

Development[]

The sprites and backgrounds were drawn by Disney animators themselves at Walt Disney Feature Animation, and the music was adapted from songs and orchestrations in the soundtrack. In a "Devs Play" session with Double Fine, game designer Louis Castle revealed that two of the game's levels, Hakuna Matata and Be Prepared, were adapted from scenes that were scrapped from the final movie.[5]

An Amiga 1200 version of the game was developed with assembly language in two months by Dave Semmons, who was willing to take on the conversion if he received the Genesis source code. He assumed the game to be programmed in 68000 assembly, since the Amiga and Genesis shared the same CPU family developed by Motorola, but turned out to be written in C, a language he was unfamiliar with.[6]

Westwood Studios developed the game for SNES, Genesis and Amiga. The development of ports for the other platforms was outsourced to different studios. East Point Software ported the game to MS-DOS, adding enhanced music and sound effects. The Sega Master System and Game Gear versions were developed by Syrox Developments, while the NES and Game Boy versions were developed by Dark Technologies.

Re-release[]

The versions of the game for SNES, Genesis, and Game Boy are included alongside Aladdin in Disney Classics: Aladdin and The Lion King, which released for the Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and Microsoft Windows on October 29, 2019.

Voice cast[]

- Jonathan Taylor Thomas as Simba (archive footage)

- James Earl Jones as Mufasa (archive footage)

- Robert Guillaume as Rafiki (archive footage)

- Nathan Lane as Timon (archive footage)

- Ernie Sabella as Pumbaa (archive footage)

- Cheech Marin as Banzai (archive footage)

Reception[]

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| EGM | SGG: 31/40[7] |

| GameFan | SNES: 268/300[8] |

| Next Generation | SNES: |

| Nintendo Power | SNES: 16.3/20[10] |

| VideoGames & Computer Entertainment | SMD & SNES: 7/10[11] |

| Electronic Games | SMD: A[12] |

| Entertainment Weekly | SMD: B+[13] SNES: A[13] |

| GB Action | GB: 85%[14] |

| Games World | SGG: 85/100[15] |

The SNES version of The Lion King sold well, with 1.27 million copies sold in the United States.[16] The MS-DOS version sold over 200,000 copies.[17] In the United Kingdom, it was the top-selling Sega Master System game in November 1994.[18] In 2002, Westwood's Louis Castle remarked that The Lion King sold roughly 4.5 million copies in total.[19]

GamePro gave the SNES version a generally negative review, commenting that the game has outstanding graphics and voices but "repetitive, tedious game play that's too daunting for beginning players and too annoying for experienced ones." They particularly noted the imprecise controls and highly uneven difficulty, though they felt the "movie-quality graphics, animations, and sounds" were good enough to make the game worth playing regardless of the gameplay.[20] They similarly remarked of the Genesis version, "The Lion King looks good and sounds great, but the game play needs a little more fine-tuning ..."[21]

The four reviewers of Electronic Gaming Monthly praised the Game Gear version as having graphics equal to the SNES and Genesis versions and controls that are vastly improved over those versions.[7] GamePro wrote that the graphics are not as good as those of the SNES and Genesis versions, but agreed that they are exceptional by Game Gear standards, and praised the Game Gear version for having a much more gradual difficulty slope than the earlier versions.[22] Gameplayers wrote in their November 1994 issue that "even on the easy setting, the game is hard for an experienced player".[citation needed]

Next Generation reviewed the SNES version of the game, rating it four stars out of five, and stated that "even though the game is much harder than Aladdin, it's never unfair or frustrating."[9]

Entertainment Weekly gave the Super NES version an A and the Genesis version a B+ and wrote that "Controlling Simba when he's a playful bundle of fur is one thing; putting him through his paces as a full-maned adult is quite another. When the grown-up Simba gives a blood-curdling roar and mauls snarling hyenas, the interaction is so well observed that it's like watching a PBS nature documentary. The sense of power it gives you is exhilarating, and by the time Simba takes his climactic heavyweight stand against his evil uncle Scar, this Lion King has turned into a wild-kingdom variant of Street Fighter II."[13] Super Play gave the Super NES version an overall score of 82/100 praising the game’s graphics and sound as “almost film-like quality” and stating “a very high-quality platformer game with little in the way of innovation.”[23]

See also[]

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Nintendo staff. "Super NES Games" (PDF). Nintendo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Game Players Vol 7, #10 pg. 10". Sega Retro. October 1994. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "Sega Magazine #11 pg. 74". Sega Retro. November 1994. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Nintendo staff. "Game Boy (original) Games" (PDF). Nintendo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ Mike Fahey. "How Westwood Made The Lion King, One Of Gaming's Finest Platformers". Kotaku UK. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "An interview with Dave Semmens". Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Review Crew: The Lion King". Electronic Gaming Monthly (65). Ziff Davis. December 1994. p. 46.

- ^ "Viewpoint - Lion King - SNES". GameFan. Vol. 2 no. 11. DieHard Gamers Club. November 1994. p. 33.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Finals". Next Generation. No. 1. Imagine Media. January 1995. pp. 102, 104.

- ^ "Now Playing". Nintendo Power. Vol. 68. January 1995. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Constant, Niko (December 1994). "The Lion King". Video Games & Computer Entertainment. No. 71. pp. 96–97. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Yates, Lauren (November 1994). "The Lion King". Electronic Games. pp. 110–111. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Lion King". Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ "The Lion King". Video Games & Computer Entertainment. No. 33. Christmas 1994. pp. 8–9. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Dave; Nick; Nick II; Adrian (December 1994). "The Lion King". Games World. No. 6. p. 21. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "US Platinum Videogame Chart". The Magic Box. Retrieved August 13, 2005.

- ^ Bateman, Selby (April 1995). "Movers & Shakers". Next Generation. Imagine Media (4): 27.

- ^ "Chart Attack with HMV" (PDF). Computer & Video Games. No. 158 (January 1995). Future plc. January 1995. p. 115.

- ^ Pearce, Celia (December 2002). "The Player with Many Faces". Game Studies. 2 (2). Archived from the original on June 27, 2003.

- ^ "ProReview: The Lion King". GamePro (64). IDG. November 1994. pp. 116–117.

- ^ "ProReview: The Lion King". GamePro (65). IDG. December 1994. pp. 90–91.

- ^ "ProReview: The Lion King". GamePro (65). IDG. December 1994. p. 220.

- ^ Leach, James (March 1995). The Lion King Review. Future Publishing. pp. 44–45.

External links[]

- The Lion King (franchise) video games

- 1994 video games

- Amiga games

- DOS games

- Game Boy games

- Sega Game Gear games

- Mobile games

- Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Platform games

- Sega Genesis games

- Master System games

- Super Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Virgin Interactive games

- Westwood Studios games

- Video games set in Africa

- Amiga 1200 games

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games scored by Allister Brimble

- Video games scored by Frank Klepacki

- Single-player video games