The Long Goodbye (film)

| The Long Goodbye | |

|---|---|

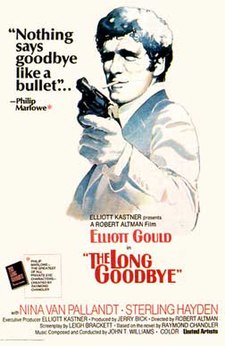

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Altman |

| Screenplay by | Leigh Brackett |

| Based on | The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler |

| Produced by | Jerry Bick |

| Starring | Elliott Gould Nina van Pallandt Sterling Hayden |

| Cinematography | Vilmos Zsigmond |

| Edited by | Lou Lombardo |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.7 million[1] |

| Box office | $959,000 |

The Long Goodbye is a 1973 American neo-noir[2][3][4] satirical mystery crime thriller film directed by Robert Altman and based on Raymond Chandler's 1953 novel. The screenplay was written by Leigh Brackett, who co-wrote the screenplay for Chandler's The Big Sleep in 1946. The film stars Elliott Gould as Philip Marlowe and features Sterling Hayden, Nina Van Pallandt, Jim Bouton (in a rare acting role), Mark Rydell and an early uncredited appearance by Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The story's period was moved from 1949–50 to 1970s Hollywood. The Long Goodbye has been described as "a study of a moral and decent man cast adrift in a selfish, self-obsessed society where lives can be thrown away without a backward glance ... and any notions of friendship and loyalty are meaningless."[5]

In 2021, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[6]

Plot[]

Late one night, private investigator Philip Marlowe is visited by his close friend Terry Lennox, who asks for a lift from Los Angeles to the California–Mexico border at Tijuana. Marlowe obliges. On returning home, Marlowe is met by two police detectives who accuse Lennox of having murdered his rich wife, Sylvia. Marlowe refuses to give them any information, so they arrest him. After he is jailed for three days, the police release him, because they have learned that Lennox has committed suicide in Mexico. The police and the press seem to believe it is an obvious case, but Marlowe does not accept the official facts.

Marlowe is hired by Eileen Wade, who asks him to find her missing husband Roger, an alcoholic novelist with writer's block whose macho, Hemingway-like persona is proving self-destructive, resulting in days-long disappearances from their Malibu home. While investigating Eileen's missing husband, Marlowe visits the subculture of private detoxification clinics for rich alcoholics and drug addicts. He locates and recovers Roger and learns that the Wades knew the Lennoxes socially, and suspects that there is more to Lennox's suicide and Sylvia's murder. Marlowe incurs the wrath of gangster Marty Augustine, who wants money returned that Lennox owed him, and threatens Marlowe by maiming his own mistress.

After a side-trip to Mexico, where officials corroborate the details of Lennox's death, Marlowe returns to the Wade house. A party breaks up after an argument over Roger's unpaid bill from the detoxification clinic. Later that night, Eileen and Marlowe are interrupted when she sees a drunken Roger wandering into the sea; before they can stop him, he drowns. Eileen confesses that Roger had been having an affair with Sylvia, and might have killed her. Marlowe tells this to the police, who tell him that Roger's time at the clinic provides an alibi.

After visiting Augustine, whose missing money has been returned, Marlowe sees Eileen driving away in her open topped Mercedes-Benz 450SL. While running after her, he is struck by a car and hospitalized. Waking up, he is given a harmonica by the heavily-bandaged patient in the next bed. Returning to Malibu, he finds the Wade house being packed up by a real estate company and Eileen gone.

He returns to Mexico, where he bribes local officials into revealing the truth. They confess to having set up Terry's apparent suicide and reveal he is alive and well in a Mexican villa. Marlowe finds Terry, who admits to killing Sylvia and reveals that he is having an affair with Eileen. Roger had discovered the affair and disclosed it to Sylvia, after which Terry killed her in the course of a violent argument. Terry gloats that Marlowe fell for his manipulations, causing Marlowe to fatally shoot Terry. As Marlowe walks away, he passes Eileen, who is on her way to meeting Terry. Marlowe pulls out his harmonica and plays it while strolling jauntily down the road.

Cast[]

- Elliott Gould as Philip Marlowe

- Nina van Pallandt as Eileen Wade

- Sterling Hayden as Roger Wade

- Mark Rydell as Marty Augustine

- Henry Gibson as Dr. Verringer

- David Arkin as Harry

- Jim Bouton as Terry Lennox

- Warren Berlinger as Morgan

- Pancho Córdova as Doctor

- Enrique Lucero as Jefe

- Rutanya Alda as Rutanya Sweet

- Jack Riley as Riley

- Jerry Jones as Det. Green

- John S. Davies as Det. Dayton

- Arnold Schwarzenegger as Hood in Augustine's Office (uncredited)[7]

Development[]

It took a number of years for a film of The Long Goodbye to be made, although there had been a television production in 1954 with Dick Powell.[8] By the time of Chandler's death, the only novels of his that had not been made into films were The Long Goodbye and Playback.

In October 1965 it was announced the rights to Goodbye were held by producers Elliott Kastner and Jerry Gershwin who would make it the following year in Los Angeles and Mexico.[9]

In 1967 producer Gabriel Katzka had the rights.[10] He wanted to make it as a follow up to their adaptation of The Little Sister (which became Marlowe).[11] Stirling Silliphant, who wrote Marlowe, did a script. However the film was not made and MGM let their option lapse.[12]

Producers Jerry Bick and Elliott Kastner bought the rights back and made a production deal with the United Artists distribution company for them to finance.[13] Sales of Chandler had been consistent over the years and in the early 1970s the author's books were selling as much as when Chandler was alive.[14]

Leigh Brackett[]

They commissioned the screenplay from Leigh Brackett, who had been Kastner's client when he was an agent and had written the script for the Humphrey Bogart version of The Big Sleep. Brackett:

... set the deal with United Artists, and they had a commitment for a film with Elliott Gould, so either you take Elliott Gould or you don't make the film. Elliott Gould was not exactly my idea of Philip Marlowe, but anyway there we were. Also, as far as the story was concerned, time had gone by—it was twenty-odd years since the novel was written, and the private eye had become a cliché. It had become funny. You had to watch out what you were doing. If you had Humphrey Bogart at the same age that he was when he did The Big Sleep, he wouldn't do it the same way. Also, we were faced with a technical problem of this enormous book, which was the longest one Chandler ever wrote. It's tremendously involuted and convoluted. If you did it the way he wrote it, you would have a five-hour film.[15]

Brian G. Hutton, who had made a number of movies for Kastner, was originally attached as director and Brackett says Hutton wanted the script structured so that "the heavy had planned the whole thing from the start" but when writing it she found the idea contrived.[15]

The producers offered the script to both Howard Hawks and Peter Bogdanovich to direct it. Both refused the offer, but Bogdanovich recommended Robert Altman.[13]

Robert Altman[]

United Artists president David Picker may have picked Gould to play Marlowe as a ploy to get Altman to direct. At the time, Gould was in professional disfavor because of his rumored troubles on the set of A Glimpse of Tiger, in which he bickered with costar Kim Darby, fought with director Anthony Harvey, and acted erratically. Consequently, he had not worked in nearly two years; nevertheless, Altman convinced Bick that Gould suited the role.[13] United Artists had Elliott Gould undergo the usual employment medical examination, and also a psychological examination attesting to his mental stability.[16]

In January 1972 it was announced Altman and Gould would make the film.[17] Altman called the film "a satire in melancholy."[18]

In adapting Chandler's book, Leigh Brackett had problems with its plot, which she felt was "riddled with cliches", and faced the choice of making it a period piece or updating it.[19] Altman received a copy of the script while shooting Images in Ireland. He liked the ending because it was so out of character for Marlowe. He agreed to direct but only if the ending was not changed.[20]

Brackett recalled meeting Altman while doing Images. "We conferred about ten o'clock in the morning and yakked all day, and I went back to the hotel and typed all the notes and went back the next day. In a week we had it all worked out. He was a joy to work with. He had a very keen story mind."[15]

Altman and Brackett spent a lot of time talking over the plot. Altman wanted Marlowe to be a loser. He even nicknamed Gould's character Rip Van Marlowe, as if he had been asleep for 20 years, had woken up, and was wandering around Los Angeles in the early 1970s but "trying to invoke the morals of a previous era".[21]

Brackett says her first draft was too long, and she shortened it, but the ending was inconclusive.[19] She had Marlowe shooting Terry Lennox.[22] Altman conceived of the film as a satire and made several changes to the script, like having Roger Wade commit suicide and having Marty Augustine smash a Coke bottle across his girlfriend's face.[22] Altman said, "it was supposed to get the attention of the audience and remind them that, in spite of Marlowe, there is a real world out there, and it is a violent world".[23]

"Chandler fans will hate my guts," said Altman. "I don't give a damn."[14]

Cast[]

Many of the key roles in the film were cast with unconventional choices. Jim Bouton, cast as Marlowe's friend Terry Lennox, was not an actor; he was a former Major League Baseball pitcher and the author of the bestselling book Ball Four. Nina Van Pallandt was best known at the time as the ex-lover of writer Clifford Irving, who had written a fake autobiography of Howard Hughes that turned into a major scandal.[24] Mark Rydell, who played vicious gangster Marty Augustine, had an acting background, but was better known as the director of films like The Cowboys and The Reivers.[25] Henry Gibson was another odd choice, having just completed four years as a cast member of the TV comedy-variety series Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In.[26]

In May 1972 it was announced Dan Blocker would appear.[27] He was cast in the role of Roger Wade. However he died before filming started. The film is dedicated to his memory in the closing credits.

In June it was announced that Vilmos Zsigmond would be cinematographer.[28]

Near the midpoint of the film, during a scene in which Marlowe meets with Marty Augustine, Augustine orders everyone to strip and we see Arnold Schwarzenegger in briefs portraying a massive thug working for Augustine. Arnold received neither screen credit nor lines in this appearance.

Principal photography[]

Altman did not read all of Chandler's book and instead used Raymond Chandler Speaking, a collection of letters and essays. He gave copies of this book to the cast and crew, advising them to study the author's literary essays.[22] The opening scene with Philip Marlowe and his cat came from a story a friend of Altman's told him about his cat only eating one type of cat food. Altman saw it as a comment on friendship.[20] The director decided that the camera should never stop moving and put it on a dolly.[29] The camera movements would counter the actions of the characters so that the audience would feel like a voyeur. To compensate for the harsh light of Southern California, Altman gave the film a soft pastel look reminiscent of old postcards from the 1940s.[29]

When it came to the scenes between Philip Marlowe and Roger Wade, Altman had Elliott Gould and Sterling Hayden ad lib most of their dialogue because, according to the director, Hayden was drunk and stoned on marijuana most of the time.[22] Altman was reportedly thrilled by Hayden's performance, despite him being second choice to Blocker. Altman's home in Malibu Colony was used as the location for the scenes that took place in Wade's house. "I hope it works," said Altman during filming. "We've got a script but we don't follow it closely."[14]

Soundtrack[]

The soundtrack of The Long Goodbye features two songs, "Hooray for Hollywood" and "The Long Goodbye", composed by John Williams and Johnny Mercer. It was Altman's idea to have every occurrence of the latter song arranged differently, from hippie chant to supermarket muzak to radio music, setting the mood for the hero's encounters with eccentric Californians, while pursuing his case.[30]

Varèse Sarabande released selections from Williams' score on a CD in 2004 paired with the album re-recording of Williams' music from Fitzwilly; in 2015 Quartet Records issued a CD entirely devoted to The Long Goodbye.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Long Goodbye (John Williams, piano soloist)" | 3:07 |

| 2. | "The Long Goodbye (Clydie King, vocal)" | 4:35 |

| 3. | "The Long Goodbye (Dave Grusin trio)" | 5:02 |

| 4. | "The Long Goodbye (Jack Sheldon, vocal)" | 3:32 |

| 5. | "The Long Goodbye (Dave Grusin trio)" | 4:33 |

| 6. | "The Long Goodbye - Tango" | 2:30 |

| 7. | "The Long Goodbye (Irene Kral & Dave Grusin trio)" | 3:11 |

| 8. | "The Long Goodbye - Mariachi" | 2:04 |

| 9. | "Marlowe in Mexico" | 3:37 |

| 10. | "Main Title Montage" | 10:58 |

| 11. | "Night Talk" | 2:08 |

| 12. | "The Border" | 0:34 |

| 13. | "Love Theme from "The Long Goodbye"" | 1:58 |

| 14. | "The Long Goodbye - Sitar" | 1:02 |

| 15. | "Guitar Nostalgia" | 1:01 |

| 16. | "The Mexican Funeral" | 2:31 |

| 17. | "Finale" | 1:08 |

| 18. | "Clydie King Adlibs Rehearsal" | 8:25 |

| 19. | "Jack Riley and Ensemble Rehearsal" | 1:39 |

| 20. | "Violin Rehearsal" | 2:06 |

Home media[]

The film was released on DVD by MGM Home Entertainment on September 17, 2002.[32]

Release and reception[]

Initial release[]

The Long Goodbye was previewed at the Tarrytown Conference Center in Tarrytown, New York. The gala was hosted by Judith Crist, then the film critic for New York magazine.[23] The film was not well received by the audience, except for Nina van Pallandt's performance. Altman attended a question-and-answer session afterward, where the mood was "vaguely hostile", reportedly leaving the director "depressed".[23]

The Long Goodbye was not well received by critics during its limited release in Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia and Miami.[1][23] Time magazine's Jay Cocks wrote, "Altman's lazy, haphazard putdown is without affection or understanding, a nose-thumb not only at the idea of Philip Marlowe but at the genre that his tough-guy-soft-heart character epitomized. It is a curious spectacle to see Altman mocking a level of achievement to which, at his best, he could only aspire".[33] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times found the film "quite sleek, marvelously and inventively photographed ... The problem is that the Altman-Brackett Marlowe, played by Elliott Gould, is an untidy, unshaven, semiliterate, dim-wit slob who could not locate a missing skyscraper and would be refused service at a hot dog stand. He is not Chandler's Marlowe, or mine, and I can't find him interesting, sympathetic or amusing, and I can't be sure who will."[34] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote that the film "is not a movie version of the Chandler mystery that anyone with a liking for Chandler could possibly enjoy ... If you are not prepared to shuffle along from scene to pointless, protracted scene with klutzy old Elliott, there will be little to occupy your time or offset your annoyance."[35]

Roger Ebert, however, gave the film three out of four stars and praised Elliott Gould's "good performance, particularly the virtuoso ten-minute stretch at the beginning of the movie when he goes out to buy food for his cat. Gould has enough of the paranoid in his acting style to really put over Altman's revised view of the private eye".[36] Gene Siskel also liked the film and gave it three-and-a-half out of four stars, calling it "a most satisfying motion picture" with Gould displaying "surprising finesse and reserve" in his performance, though he faulted the "convoluted and too quickly resolved plot."[37]

The New York opening was canceled at the last minute after several advance screenings had already been held for the press. The film was abruptly withdrawn from release with rumors that it would be re-edited.[23]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 94% based on 47 reviews, with an average rating of 8.40/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "An ice-cold noir that retains Robert Altman's idiosyncratic sensibilities, The Long Goodbye ranks among the smartest and most satisfying Marlowe mysteries."[38] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 87 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating "universal acclaim."[39]

Re-release[]

Studio executives analyzed the reviews for months, concluding that the reason for the film's failure was the misleading advertising campaign in which it had been promoted as a "detective story". They spent $40,000 on a new release campaign, which included a poster by Mad magazine artist Jack Davis.[40][41]

When The Long Goodbye was re-released, reviewer Vincent Canby wrote, "it's an original work, complex without being obscure, visually breathtaking without seeming to be inappropriately fancy".[42]

Pauline Kael's lengthy review in The New Yorker called the film "a high-flying rap on Chandler and the movies", hailed Gould's performance as "his best yet" and praised Altman for achieving "a self-mocking fairy-tale poetry".[43]

Despite Kael's effusive endorsement and its influence among younger critics, The Long Goodbye was relatively unpopular and earned poorly in the rest of the United States. The New York Times listed it in its Ten Best List for film for that year, while Vilmos Zsigmond was awarded the National Society of Film Critics' prize for Best Cinematographer.[41][44] Ebert later ranked it among his Great Movies collection and wrote, "Most of its effect comes from the way it pushes against the genre, and the way Altman undermines the premise of all private eye movies, which is that the hero can walk down mean streets, see clearly, and tell right from wrong".[45]

Changes from the novel[]

The 1973 cinematic adaptation deviates markedly from the 1953 novel. Screenwriter Leigh Brackett took many literary liberties with the story, plot and characters of The Long Goodbye in her adaptation. In the film, Marlowe kills his best friend, Terry Lennox. Lennox did kill his own wife, because she discovered he was having an affair with Eileen, and he admits this to Marlowe. The father of millionairess Sylvia Lennox, as well as her sister, do not appear in the film; Roger Wade commits suicide in the film, rather than being murdered; and gangster Marty Augustine and his subplots are additions to the film. Bernie Ohls, Marlowe's sometime-friend on the LAPD, is also absent.

The film quotes from the novel when Marlowe, under police interrogation, asks, "Is this where I'm supposed to say, 'What's all this about?' and he [the cop] says, 'Shut up! I ask the questions'?"[46]

Throughout the film are stylistic nods to the Chandler novels and 1950s American culture. Marlowe drives a 1948 Lincoln Continental Convertible Cabriolet, in contrast with the contemporary cars driven by others in the film. Marlowe also chain smokes in the film, in contrast with a health-conscious California; no one else smokes on screen. As a reference to the American iconography which Chandler used in his novels, Marlowe wears a tie with American flags on it (the tie looks plain red in the movie due to cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond's post-flashing).[47]

A "making-of" featurette on the DVD is entitled "Rip van Marlowe", a reference to the character Rip Van Winkle, to emphasize the contrast between Marlowe's anachronistic 1950s behavior and the film's 1970s setting.[47]

Later screenings[]

When the film screened on TV in 1977, ABC cut off the final shooting.[48]

Legacy[]

Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017), the soundtrack of which was also composed by John Williams, briefly samples Williams's own theme for The Long Goodbye (lyrics by Johnny Mercer) during Finn and Rose's escape, although this was not included in the official soundtrack release. This is one of the few times that a Star Wars soundtrack incorporated a song from outside the Star Wars universe.[49]

See also[]

- List of American films of 1973

- Robert Altman Filmography

References[]

Notes

- ^ a b Long Goodbye' Proves a Big Sleeper Here By PAUL GARDNER. New York Times 8 Nov 1973: 59.

- ^ Putvinski, Anthony (2013-02-15). "Altman Defines Neo Noir with The Long Goodbye • Movie Fail". Movie Fail. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ "'The Long Goodbye': Robert Altman and Leigh Brackett's Unique and Fascinating Take on Chandler and Film Noir • Cinephilia & Beyond". Cinephilia & Beyond. 2017-01-03. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ Gore, Father (2016-06-07). "Altman's The Long Goodbye is Perfect Post-Modern Film Noir". Father Son Holy Gore. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ O'Brien, Daniel. Robert Altman: Hollywood Survivor. London: B.T. Batsford, 1995. p. 53. ISBN 9780713474817. See also:

Phillips, Gene C. (2000). Creatures of Darkness: Raymond Chandler, Detective Fiction and Film Noir. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 156 and 265. ISBN 0813121744 - ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (December 14, 2021). "National Film Registry Adds Return Of The Jedi, Fellowship Of The Ring, Strangers On A Train, Sounder, WALL-E & More". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ "A true 'hot property': Elliott Gould's 'Long Goodbye' apartment is for rent!". Los Angeles Times. 3 December 2014.

- ^ Television in Review: 'Climax': Raymond Chandler Play Opens C.B.S. Series Teresa Wright and Dick Powell in Lead Roles By JACK GOULD. New York Times 08 Oct 1954: 34.

- ^ Gene Kelly Readies Musical Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times 13 Oct 1965: d12.

- ^ Bobby Morse to Co-Star Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times 10 June 1967: b7.

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: 'Little Sister' on Schedule Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times 12 Mar 1968: c13.

- ^ Fade-out on Raymond Chandler Lochte, Richard S. Chicago Tribune 14 Dec 1969: 60.

- ^ a b c McGilligan 1989, p. 360.

- ^ a b c Goodbye, Mr. Marlowe Michaels, Ken. Chicago Tribune (1963-1996); Chicago, Ill. [Chicago, Ill]03 Dec 1972: 88.

- ^ a b c Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s By Patrick McGilligan p23

- ^ McGilligan 1989, p. 361.

- ^ Gould, Altman Team for 'Long Goodbye' Haber, Joyce. Los Angeles Times 27 Jan 1972: f12.

- ^ Altman, Gould Reunited for 'Goodbye' Warga, Wayne. Los Angeles Times 23 July 1972: u1

- ^ a b McGilligan 1989, p. 363.

- ^ a b Thompson 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d McGilligan 1989, p. 364.

- ^ a b c d e McGilligan 1989, p. 365.

- ^ Smith, Harrison (December 29, 2017). "Clifford Irving: Author whose literary hoax fooled America in the Seventies and inspired a Hollywood film". The Independent. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ "Mark Rydell". IMDb. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ "Henry Gibson". IMDb. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: Blocker, Gould to Costar Los Angeles Times (1923-1995); Los Angeles, Calif. [Los Angeles, Calif]05 May 1972: g22.

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: Redford Picked as 'Gatsby' Murphy, Mary. Los Angeles Times (1923-1995); Los Angeles, Calif. [Los Angeles, Calif]08 June 1972: h17.

- ^ a b Thompson 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 80.

- ^ "The Long Goodbye: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". Quartet Records. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ Rivero, Enrique (May 23, 2002). "MGM Preserves Zsigmond's Vision With 'Goodbye". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2002. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ Cocks, Jay (April 9, 1973). "A Curious Spectacle". Time. Archived from the original on January 13, 2005. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (March 8, 1973). "A Private Eye's Honor, Blackened". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (March 22, 1973). "The Long Goodbye". The Washington Post. D19.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 7, 1973). "The Long Goodbye". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (March 27, 1973). "The Long Goodbye". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 4.

- ^ "The Long Goodbye (1973)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ The Long Goodbye at Metacritic

- ^ Gardner, Paul (November 8, 1973). "Long Goodbye Proves a Big Sleeper Here". The New York Times.

- ^ a b McGilligan 1989, p. 367.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 18, 1973). "For The Long Goodbye A Warm Hello". The New York Times.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (October 22, 1973). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. 133-137.

- ^ McGilligan 1989, p. 362.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (April 23, 2006). "Great Movies: The Long Goodbye". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ The Long Goodbye, Houghton Mifflin, p. 28

- ^ a b Rip Van Marlowe, Director Greg Carson, 2002.

- ^ Deeb, Gary (29 July 1977). "'Long Goodbye' was a short one". Chicago Tribune. p. II-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017), retrieved 2017-12-30

Bibliography

- McGilligan, Patrick. Robert Altman: Jumping off the Cliff. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989.

- Thompson, David. Altman on Altman. London: Faber and Faber. 2005.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Long Goodbye (film) |

- 1973 films

- English-language films

- 1970s thriller films

- 1970s crime thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American detective films

- American films

- American mystery films

- American neo-noir films

- American satirical films

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on works by Raymond Chandler

- Films directed by Robert Altman

- Films produced by Elliott Kastner

- Films scored by John Williams

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films with screenplays by Leigh Brackett

- United Artists films

- United States National Film Registry films