The Master Thief

| The Master Thief | |

|---|---|

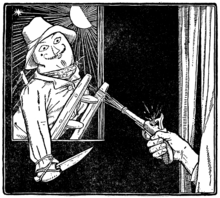

The lord mistakingly shoots the decoy dummy. Illustration from Joseph Jacobs's Europa's Fairy Book (1916) by John D. Batten. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Master Thief |

| Also known as | Mestertyven; Die Meisterdieb |

| Data | |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | 1525A |

| Country | Norway |

| Published in |

|

"The Master Thief" is a Norwegian fairy tale collected by Peter Chr. Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe.[1][2] The Brothers Grimm included a shorter variant as tale 192 in their fairy tales. Andrew Lang included it in The Red Fairy Book. George Webbe Dasent included a translation of the tale in Popular Tales From the Norse.[3] It is Aarne–Thompson type 1525A, Tasks for a Thief.

Synopsis[]

A poor cottager had nothing to give his three sons, so he walked with them to a crossroad, where each son took a different road. The youngest went into a great woods, and a storm struck, so he sought shelter in a house. The old woman there warned him that it is a den of robbers, but he stayed, and when the robbers arrived, he persuaded them to take him on as a servant.

They set him to prove himself by stealing an ox that a man brought to market to sell. He took a shoe with a silver buckle and left it in the road. The man saw it and thought it would be good if only he had the other, and went on. The son took the shoe and ran through the countryside, to leave it in the road again. The man left his ox and went back to find the other, and the son drove the ox off.

The man went back to get the second ox to sell it, and the robbers told the son that if he stole that one as well, they would take him into the band. The son hanged himself up along the way, and when the man passed, ran on and hanged himself again, and then a third time, until the man was half-convinced that it was witchcraft and went back to see if the first two bodies were still hanging, and the son drove off his ox.

The man went for his third and last ox, and the robbers said that they would make him the band's leader if he stole it. The son made a sound like an ox bellowing in the woods, and the man, thinking it was his stolen oxen, ran off, leaving the third behind, and the son stole that one as well.

The robbers were not pleased with his leading the band, and so they all left him. The son drove the oxen out, so they returned to their owner, took all the treasure in the house, and returned to his father.

He decided to marry the daughter of a local squire and sent his father to ask for her hand, telling him to tell the squire that he was a Master Thief. The squire agreed, if the son could steal the roast from the spit on Sunday. The son caught three hares and released them near the squire's kitchen, and the people there, thinking it was one hare, went out to catch it, and the son got in and stole the roast.

The priest made fun of him, and when the Master Thief came to claim his reward, the squire asked him to prove his skill further, by playing some trick on the priest. The Master Thief dressed up as an angel and convinced the priest that he was come to take him to heaven. He dragged the priest over stones and thorns and threw him into the goose-house, telling him it was purgatory, and then stole all his treasure.

The squire was pleased, but still put off the Master Thief, telling him to steal twelve horses from his stable, with twelve grooms in their saddles. The Master Thief prepared and disguised himself as an old woman to take shelter in the stable, and when the night grew cold, drank brandy against it. The grooms demanded some, and he gave them a drugged drink, putting them to sleep, and stole the horses.

The squire put him off again, asking if he could steal a horse while he was riding it. The Master Thief said he could, and disguised himself as an old man with a cask of mead, and put his finger in the hole, in place of the tap. The squire rode up and asked him if he would look in the woods, to be sure that the Master Thief did not lurk there. The Master Thief said that he could not, because he had to keep the mead from spilling, and the squire took his place and lent him his horse to look.

The squire put him off again, asking if he could steal the sheet off his bed and his wife's shift. The Master Thief made up a dummy like a man and put it at the window, and the squire shot at it. The Master Thief let it drop. Fearing talk, the squire went to bury it, and the Master Thief, pretending to be the squire, got the sheet and the shift on the pretext they were needed to clean the blood up.

The squire decided that he was too afraid of what the thief would steal next, and let him marry his daughter.

Analysis and formula[]

"The Master Thief" is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as ATU 1525 and subtypes. Folklorist Stith Thompson argues the story can be found in tale collections from Europe, Asia and all over the world.[4]

Folklorist Joseph Jacobs wrote a reconstrution of the tale, with the same name, in his Europa's Fairy Book, following a formula he specified in his commentaries.[5]

The motif of the impossible thievery can be found in a story engraved in a Babylonian tablet with the tale of the Poor Man of Nippur.[6][7]

Joseph Jacobs, in his book More Celtic Fairy Tales,[8] mentions an Indian folkloric character named "Sharaf, the Thief" (Sharaf Tsúr; or Ashraf Chor).[9]

Folklorist and scholar Richard Dorson cited the opinions of two scholars about the origins of the tale type: Alexander H. Krappe suggested an Egyptian origin for the tale, while W. A. Clouston proposed an Asiatic provenance.[10]

Variants[]

- An earlier literary variant is Cassandrino, The Master-Thief, by Straparola in his The Facetious Nights.[11]

- , following Johannes Bolte and Jiri Polívka's Anmerkungen (1913),[12] lists Spanish picaresque novel Guzmán de Alfarache (1599) as a predecessor of the tale-type.[13]

- The Grimm Brothers' version begins with the son's arrival home, and the squire sets him the tasks of stealing the horses from the stable, the sheet and his wife's wedding ring, and the parson and clerk from the church as tests of skill, or he would hang him. The thief succeeds and leaves the country.

- German scholar Johann Georg von Hahn compared 6 variants he collected in Greece to the tale in the Brothers Grimm's compilation.[14]

- 19th century poet and novelist Clemens Brentano collected a variant named Witzenspitzel. His work was translated as Wittysplinter and published in The Diamond Fairy Book.[15][16]

- Variants of the tale and subtypes of the ATU 1525 are reported to exist in American and English compilations.[17]

- A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage"), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found the existence of variants and subtypes of the tale across Italian sources, grouped under the name Mastro Ladro.[18]

- Northern India folklore also attests the presence of two variants of the tale, this time involving a king's son as the "Master-Thief".[19]

- Irish folklorist Patrick Kennedy also listed Jack, The Cunning Thief as another variant of the Shifty Lad and, by extension, of The Master Thief cycle of stories.[20]

- Another Irish variant, The Apprentice Thief, was published anonymously in compilation The Royal Hibernian Tales.[21] In a third homonymous Irish variant, the king challenges young Jack, son of Billy Brogan, to steal three things without the King noticing.[22]

- In the Irish tale How Jack won a Wife, the Master Thief character, Jack, fulfills the squire's challenges to prove his craft and marries the squire's daughter.[23]

- Svend Grundtvig collected a Danish variant, titled Hans Mestertyv.[24]

- According to Professor Bronislava Kerbelytė, the story of the Master Thief is reported to contain several variants in Lithuania: 284 (two hundred and eighty-four) variants of the AT 1525A, "The Crafty Thief", and 216 (two hundred and sixteen) variants of AT 1525D, "Theft by Distracting Attention", both versions with and without contamination from other tale types.[25]

- Professor Andrejev noted that the tale type 1525A, "The Master Thief", was one of "the most populär tale types" across Ukrainian sources, with 28 variants, as well as "in the Russian material", with 19 versions.[26]

- Folklorist Stith Thompson argued that similarities between the European "Master Thief" tales and Native American trickster tales led to the merging of motifs, and the borrowing may have originated from French Canadian tales.[27]

- Anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons collected variants of the tale in Caribbean countries.[28]

Modern adaptations[]

In a storybook and cassette in the Once Upon a Time Fairy Tale series, the Squire is called the Count and the tasks he gives the thief are to steal his horse, the bedsheet and the Parson and Sexton from the church. When he has succeeded, the Count tells him if he changes his ways, he will make him Governor of the town. The Thief agrees, promising never to steal anything again.

See also[]

- How the Dragon was Tricked

- The Tale of the Shifty Lad, the Widow's Son

References[]

- ^ "The Master Thief." In True and Untrue and Other Norse Tales, edited by Undset Sigrid, by Chapman Frederick T., pp. 213–32. University of Minnesota Press, 1972. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt4cgg4g.27.

- ^ Asbjørnsen, Peter Christen, Jørgen Moe, Tiina Nunnally, and Neil Gaiman. "The Master Thief." In: The Complete and Original Norwegian Folktales of Asbjørnsen and Moe, pp. 140–52. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2019. doi:10.5749/j.ctvrxk3w0.38.

- ^ Dasent, George Webbe. Popular Tales from the Norse. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. 1912. pp. 232–251.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. pp. 174–176. ISBN 978-0520035379

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam's sons. 1916. pp. 245–246.

- ^ Johnston, Christopher. "Assyrian and Babylonian Beast Fables." The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 28, no. 2 (1912): 81–100. www.jstor.org/stable/528119.

- ^ Jason, Heda and Kempinski, Aharon. "How Old Are Folktales?". In: Fabula 22, no. Jahresband (1981): 4-5. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1981.22.1.1

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. More Celtic Fairy Tales. New York. G. P. Putnam's Sons. 1895. p. 224.

- ^ Knowles, James Hinton. Folk-tales of Kashmir. London: Trübner. 1888. pp. 338–352.

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. "Polish Wonder Tales of Joe Woods". In: Western Folklore 8, no. 1 (1949): 47 (footnote nr. 8). Accessed 8 March 2021. doi:10.2307/1497158.

- ^ "Cassandrino the Master-Thief." In The Pleasant Nights – Volume 1, edited by Beecher Donald, by Waters W.G., 172-98. Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto Press, 2012. www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442699519.8.

- ^ Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Dritter Band (NR. 121-225). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 379–406.

- ^ Boggs, Ralph Steele. Index of Spanish folktales, classified according to Antti Aarne's "Types of the folktale". Chicago: University of Chicago. 1930. pp. 129–130.

- ^ Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1–2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller. 1918 [1864]. pp. 290–302.

- ^ [no known authorship]. The Diamond Fairy Book. Illustrations by Frank Cheyne Papé and H. R. Millar. London: Hutchinson. [1897?]. pp. 127–143.

- ^ Blamires, David. "Clemens Brentano’s Fairytales." In: Telling Tales: The Impact of Germany on English Children’s Books 1780–1918, 263–74. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Open Book Publishers, 2009. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vjt8c.18.

- ^ Baughman, Ernest Warren. Type and Motif-index of the Folktales of England and North America. Indiana University Folklore Series No. 20. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton & Co. 1966. p. 37.

- ^ Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral and Non Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Motifs or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. pp. 323–326.

- ^ Crooke, William; Chaube, Pandit Ram Gharib. Folktales from Northern India. Classic Folk and Fairy Tales. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. 2002. pp. 100–103 and 103–105. ISBN 1-57607-698-9

- ^ Kennedy, Patrick. The fireside stories of Ireland. Dublin: M'Glashan and Gill: P. Kennedy. 1870. pp. 38–46 and 165.

- ^ The Royal Hibernian Tales: Being a Collection of the Most Entertaining now Extant. Dublin: C. M. Warren. [no date]. pp. 28–39. [1]

- ^ MacManus, Seumas. In chimney corners: Merry tales of Irish folk-lore. New York, Doubleday & McClure Co. 1899. pp. 207–223.

- ^ Johnson, Clifton. The Elm-tree Fairy Book: Favorite Fairy Tales. Boston: Little, Brown, 1908. pp. 233–253. [2]

- ^ Grundtvig, Svend. Gamle Danske Minder I Folkemunde. Kjøbenhavn: C. G. Iversen, 1861. pp. 68–72. [3]

- ^ Skabeikytė-Kazlauskienė, Gražina. Lithuanian Narrative Folklore: Didactical Guidelines. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University. 2013. p. 41. ISBN 978-9955-21-361-1

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. "A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus". In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 237. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Thompson, Stith. European Tales Among the North American Indians: a Study In the Migration of Folk-tales. Colorado Springs: Colorado College. 1919. pp. 426–430.

- ^ Parsons, Elsie Worthington Clews. Folk-lore of the Antilles, French And English. Part 3. New York: American Folk-lore Society. 1943. pp. 215–217.

Bibliography[]

- Cosquin, Emmanuel. Contes populaires de Lorraine comparés avec les contes des autres provinces de France et des pays étrangers, et précedés d'un essai sur l'origine et la propagation des contes populaires européens. Tome II. Deuxiéme Tirage. Paris: Vieweg. 1887. pp. 274–281.

External links[]

- Norwegian fairy tales

- Grimms' Fairy Tales

- Fictional thieves