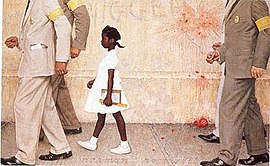

The Problem We All Live With

| The Problem We All Live With | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Norman Rockwell |

| Year | 1964 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 91 cm × 150 cm (36 in × 58 in) |

| Location | Norman Rockwell Museum[1], Stockbridge, Massachusetts |

The Problem We All Live With is a painting by Norman Rockwell that was considered an iconic image of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.[2] It depicts Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old African-American girl, on her way to William Frantz Elementary School, an all-white public school, on November 14, 1960, during the New Orleans school desegregation crisis. Because of threats of violence against her, she is escorted by four deputy U.S. marshals; the painting is framed so that the marshals' heads are cropped at the shoulders.[3][4] On the wall behind her are written the racial slur "nigger" and the letters "KKK"; a smashed and splattered tomato thrown against the wall is also visible. The white protesters are not visible, as the viewer is looking at the scene from their point of view.[3] The painting is oil on canvas and measures 36 inches (91 cm) high by 58 inches (150 cm) wide.[5]

History[]

The painting was originally published as a centerfold in the January 14, 1964, issue of Look.[5] Rockwell had ended his contract with the Saturday Evening Post the previous year due to frustration with the limits the magazine placed on his expression of political themes, and Look offered him a forum for his social interests, including civil rights and racial integration.[3] Rockwell explored similar themes in Southern Justice (Murder in Mississippi) and New Kids in the Neighborhood;[6] unlike his previous works for the Post, The Problem We All Live With and these others place black people as sole protagonists, instead of as observers, part of group scenes, or in servile roles.[7][8] Like New Kids in the Neighborhood, The Problem We All Live With depicts a black child protagonist;[7] like Southern Justice, it uses strong light-dark contrasts to further its racial theme.[9]

While the subject of the painting was inspired by Ruby Bridges, Rockwell used a local girl, Lynda Gunn, as the model for his painting;[10] her cousin, Anita Gunn, was also used.[11] One of the marshals was modelled by William Obanhein.[11]

After the work was published, Rockwell received "sacks of disapproving mail", one example accusing him of being a race traitor.[11]

Legacy[]

At Bridges' suggestion, President Barack Obama had the painting installed in the White House, in a hallway outside the Oval Office, from July to October 2011. Art historian William Kloss stated, "The N-word there – it sure stops you. There's a realistic reason for having the graffiti as a slur, [but] it's also right in the middle of the painting. It's a painting that could not be hung even for a brief time in the public spaces [of the White House]. I'm pretty sure of that."[1]

The painting was used to "dress" O. J. Simpson's house during his 1995 murder trial by defense attorney Johnnie Cochran. Cochran hoped to evoke the sympathy of visiting jurors, who were mostly black, by including "something depicting African-American history."[12]

See also[]

- Civil rights movement in popular culture

- Desegregated public schools in New Orleans

- McDonogh Three

- Trying to Trash Betsy DeVos

- Art in the White House

References[]

- ^ a b Gerstein, Josh (August 24, 2011). "Norman Rockwell painting sends rare White House message on race". Politico. p. 1, 2.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (2013). American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 378. ISBN 9780374113094.

- ^ a b c Halpern, Richard (2006). Norman Rockwell: the underside of innocence. University of Chicago Press. pp. 124–31.

- ^ Greene, Bob (September 4, 2011). "America's glory in a civil rights painting". CNN.

- ^ a b ""The Problem We All Live With," Norman Rockwell, 1963. Oil on canvas, 36" x 58". Illustration for "Look," January 14, 1964. Norman Rockwell Museum Collection. ©NRELC, Niles, IL". Norman Rockwell Museum. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ^ "O say, can you see". The Economist. December 25, 1993 – January 7, 1994.

- ^ a b Grant, Daniel (July 24, 1989). "Exhibit Offers Clues to Rockwell's Sentiments". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "Exile on Main Street". The Economist. December 2, 1999.

- ^ Claridge, Laura P (2001). Norman Rockwell: A Life. Random House.

- ^ Bradway, Rich (October 6, 2019). "Remembering Lynda Jean Gunn - Norman Rockwell Museum - The Home for American Illustration".

- ^ a b c Carson, Tom (19 February 2020). "The true story of the awakening of Norman Rockwell". Vox. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard, "Shedding Light on How Simpson's Lawyers Won", The New York Times, October 16, 1996.

External links[]

Media related to The Problem We All Live With at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Problem We All Live With at Wikimedia Commons- President Obama talking with Ruby Bridges, The Problem We All Live With painting (YouTube.com-The White House channel)

- Detailed record of the painting via the Norman Rockwell Museum website

- 2020 Vox.com article about Rockwell and the painting

- Paintings by Norman Rockwell

- School segregation in the United States

- Art based on actual events

- Black people in art

- Works originally published in Look (American magazine)

- 1964 paintings

- Civil rights movement in popular culture

- Art in the White House