The Wolf of Wall Street (2013 film)

| The Wolf of Wall Street | |

|---|---|

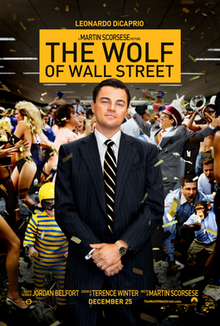

Theatrical release poster | |

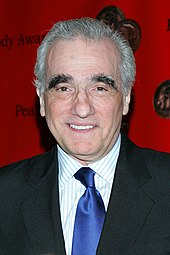

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Screenplay by | Terence Winter |

| Based on | The Wolf of Wall Street by Jordan Belfort |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Rodrigo Prieto |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 180 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $100 million[2] |

| Box office | $392 million[2] |

The Wolf of Wall Street is a 2013 American epic biographical black comedy crime film directed by Martin Scorsese and written by Terence Winter, based on the 2007 memoir of the same name by Jordan Belfort. It recounts Belfort's perspective on his career as a stockbroker in New York City and how his firm, Stratton Oakmont, engaged in rampant corruption and fraud on Wall Street, which ultimately led to his downfall. Leonardo DiCaprio, who was also a producer on the film, stars as Belfort, with Jonah Hill as his business partner and friend, Donnie Azoff, Margot Robbie as his wife, Naomi Lapaglia, and Kyle Chandler as FBI agent Patrick Denham, who tries to bring Belfort down.

The film premiered in New York City on December 17, 2013, and was released in the United States on December 25, 2013, by Paramount Pictures, and was the first major American film to be released exclusively through digital distribution.[3] It was a major commercial success, grossing $392 million worldwide during its theatrical run, becoming Scorsese's highest-grossing film.[4] The film sparked controversy over its morally ambiguous depiction of events, lack of sympathy for victims, explicit sexual content, extreme profanity, depiction of hard drug use, and the use of animals during production. It set a Guinness World Record for the most instances of swearing in a film.

The film received generally positive reviews from critics, along with some moral censure. It was nominated for several awards, including five at the 86th Academy Awards ceremony: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor (for DiCaprio) and Best Supporting Actor (for Hill). DiCaprio won Best Actor – Musical or Comedy at the 71st Golden Globe Awards, where the film was also nominated for Best Picture – Musical or Comedy.

Plot[]

In 1987, Jordan Belfort lands a job as a Wall Street stockbroker for L.F. Rothschild, employed under Mark Hanna. He is quickly enticed into the drug-fueled stockbroker culture and Hanna's belief that a broker's only goal is to make money for himself. Jordan loses his job following Black Monday, the largest one-day stock market drop in history, and takes a job at a boiler room brokerage firm on Long Island that specializes in penny stocks. Thanks to his aggressive pitching style and the high commissions, Jordan makes a small fortune.

Jordan befriends his neighbor Donnie Azoff, and the two found their own company. They recruit several of Jordan's friends, whom Jordan trains in the art of the "hard sell". Jordan's tactics and salesmanship largely contribute to the success of his pump and dump scheme, which involves inflating the price of a stock through issuing misleading, positive statements in order to sell it at an artificially augmented price. When the perpetrators of the scheme sell their overvalued securities, the price drops immensely and those who were conned into buying at the inflated price are left with stock that is suddenly worth much less than what they paid. To cloak this, Jordan gives the firm the respectable-sounding name Stratton Oakmont in 1989.

After an exposé in Forbes, hundreds of ambitious young financiers flock to his company. Jordan becomes immensely successful and slides into a decadent lifestyle of prostitutes and drugs. He has an affair with a woman named Naomi Lapaglia; when his wife finds out, Jordan divorces her and marries Naomi in 1991. Meanwhile, the SEC and the FBI begin investigating Stratton Oakmont.

In 1993, Jordan illegally makes $22 million in three hours upon securing the IPO of Steve Madden. This brings him and his firm further to the attention of the FBI. To hide his money, Jordan opens a Swiss bank account with corrupt banker Jean-Jacques Saurel in the name of Naomi's Aunt Emma, who is a British national and thus outside the reach of American authorities. He uses the wife and in-laws of his friend Brad Bodnick, who have European passports, to smuggle the cash into Switzerland.

Donnie and Brad get into a public brawl; Donnie escapes, but Brad is arrested. Brad does not say a word about Donnie or Jordan to the police. Jordan learns from his private investigator that the FBI is wiretapping his phones. Fearing for his son, Jordan's father advises him to leave Stratton Oakmont and lie low while Jordan's lawyer negotiates a deal to keep him out of prison. Jordan, however, cannot bear to quit and talks himself into staying in the middle of his farewell speech. In 1996, Jordan, Donnie and their wives are on a yacht trip to Italy when they learn that Aunt Emma has died of a heart attack. Jordan decides to travel to Switzerland immediately to settle the bank account. To bypass border controls, he orders his yacht captain to sail to Monaco, but the ship capsizes in a storm. After their rescue, the plane sent to take them to Geneva is destroyed when a seagull flies into the engine; Jordan takes this as a sign from God and decides to sober up.

Two years later, the FBI arrests Jordan because Saurel, arrested in Florida on an unrelated charge, has informed the FBI on Jordan. Since the evidence against him is overwhelming, Jordan agrees to gather evidence on his colleagues in exchange for leniency. At home, Naomi tells Jordan she is divorcing him and wants full custody of their daughter and infant son; in an impulsive, cocaine-fueled rage, Jordan assaults Naomi and tries to drive away with his daughter before crashing his car in the driveway. Later on, Jordan wears a wire to work but slips a note to Donnie, warning him. The FBI discovers this, arrests Jordan, and raids and shuts down Stratton Oakmont. Despite breaching his deal, Jordan receives a reduced sentence of 36 months in a minimum security prison for his testimony, and is released after serving 22 months. After his release, Jordan makes a living hosting seminars on sales technique.

Cast[]

- Leonardo DiCaprio as Jordan Belfort

- Jonah Hill as Donnie Azoff (Danny Porush)

- Margot Robbie as Naomi Lapaglia

- Kyle Chandler as FBI Agent Patrick Denham

- Rob Reiner as Max Belfort

- Jon Bernthal as Brad Bodnick

- Matthew McConaughey as Mark Hanna

- Jon Favreau as Manny Riskin

- Jean Dujardin as Jean-Jacques Saurel

- Joanna Lumley as Aunt Emma

- Cristin Milioti as Teresa Petrillo

- Christine Ebersole as Leah Belfort

- Shea Whigham as Captain Ted Beecham

- Katarina Čas as Chantalle Bodnick

- Stephanie Kurtzuba as Kimmie Belzer

- P. J. Byrne as Nicky Koskoff

- Kenneth Choi as Chester Ming

- Brian Sacca as Robbie Feinberg

- Henry Zebrowski as Alden Kupferberg

- Ethan Suplee as Toby Welch

- Jake Hoffman as Steve Madden

- Mackenzie Meehan as Hildy Azoff

- Bo Dietl as himself

- Jon Spinogatti as Nicholas

- Aya Cash as Janet

- Jordan Belfort as Auckland Straight Line Host

- Catherine Curtin as FBI Agent

- Stephen Kunken as Jerry Fogel

- Barry Rothbart as Peter DeBlasio

- Welker White as Waiter

- Danny Flaherty as Zip (Lude Buying Teenager #1)

- Ted Griffin as Agent Hughes

- Steven Boyer and Danny A. Abeckaser as Investor Center Brokers

- J. C. MacKenzie as Lucas Solomon

- Ashlie Atkinson as Rochelle Applebaum

- Thomas Middleditch as Stratton Broker in a Bowtie

- Fran Lebowitz as the Honorable Samantha Stogel

- Spike Jonze as Dwayne (uncredited)[5]

Production[]

Development[]

In 2007, Leonardo DiCaprio and Warner Bros. won a bidding war for the rights to Jordan Belfort's memoir The Wolf of Wall Street, with Belfort making $1 million off the deal.[6][7] Having worked on writing the film's script, Martin Scorsese was considered to direct the film but abandoned the project to work on Shutter Island (2010).[8] He describes having "wasted five months of [his] life" without getting a green light on production dates by the Warner Bros. studio.[7] In 2010, Warner Bros. had offered the directorial role to Ridley Scott, with Leonardo DiCaprio playing the male lead,[9] but the studio eventually abandoned the project.[10]

In 2012, a green light was given by the independent company Red Granite Pictures, imposing no content restrictions. Scorsese, knowing there would be no limits to the content he would produce, came back on board, resulting in an R rating.[11] Red Granite Pictures also asked Paramount Pictures to distribute the film;[12] Paramount Pictures agreed to distribute the film in North America and Japan, but passed on the rest of the international market.[13] The rights to internationally distribute the film were acquired by Universal Pictures.[14]

According to Jordan Belfort,[15] Random House asked him to tone down or excise the depictions of debauchery in some passages of his memoir before publication, especially those relating to his bachelor party which featured acts of zoophilia, rampant use of drugs and nitrous oxide, and a particularly "disturbing" act which he recounted in Logan Paul's podcast;[16] neither the published version of the memoir nor the film contain references to this.[17]

In the film, most of the real-life characters' names have been changed from Belfort's original memoir. Donnie Azoff is based on Danny Porush. The name was changed after Porush threatened to sue the filmmakers. Porush maintains that much of the film was fictional and that Donnie Azoff was not in fact an accurate depiction of him.[18][19] Former Donna Karan Jeanswear CEO Elliot Lavigne does not appear explicitly in the film, but an incident recounted in the book, in which Belfort gives Lavigne mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to save him from choking to death, is similar to a scene in the film involving Donnie. The FBI agent known as Patrick Denham is the stand-in for real-life Gregory Coleman,[20] and lawyer Manny Riskin is based on Ira Sorkin.[21] Belfort's first wife Denise Lombardo is renamed Teresa Petrillo, while second wife Nadine Caridi became Naomi Lapaglia on-screen. In contrast, Mark Hanna's name remains the same as the LF Rothschild stockbroker who, like Belfort, was convicted of fraud and served time in prison.[22][23] Belfort's parents Max and Leah Belfort's names remained the same for the film.[24] The role of Aunt Emma was initially offered to Julie Andrews, who refused it as she was recovering from an ankle injury, and she was replaced by Joanna Lumley.[25] In January 2014, Jonah Hill revealed in an interview with Howard Stern that he had made only $60,000 on the film (the lowest possible SAG-AFTRA rate for his amount of work), while his co-star Leonardo DiCaprio (who also produced) received $10 million.[26][27][28]

Filming[]

Filming began on August 8, 2012, in New York City.[29] Jonah Hill announced on Twitter that his first day of shooting was September 4, 2012.[30] Filming also took place in Closter, New Jersey, and Harrison, New York.[31][32] Vitamin D powder was used as the fake substance for cocaine in the film; Jonah Hill was hospitalized with bronchitis due to snorting large quantities over the course of filming.[33]

Scorsese's longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker, who has received seven Academy Award nominations for Best Film Editing, stated that the film would be shot digitally instead of on film.[34] Scorsese had been a proponent of shooting on film, but decided to shoot Hugo digitally because it was being photographed in 3D. Despite being filmed in 2D, The Wolf of Wall Street was originally planned to be shot digitally.[35] Schoonmaker expressed her disappointment with the decision: "It would appear that we've lost the battle. I think Marty just feels it's unfortunately over, and there's been no bigger champion of film than him."[34] After extensive comparison tests during pre-production, eventually the majority of the film was shot on film stock, while scenes that used green screen effects or low light were shot with the digital Arri Alexa camera system.[35] The film contains 400–450 VFX shots.[36]

Profanity[]

The film set a Guinness World Record for the most instances of swearing in a motion picture.[37] The word "fuck" is used 569 times in the film, averaging 2.81 times per minute.[38][39][40] The previous record holders were Scorsese's 1995 gangster film Casino, which had 422 uses of the word, including in the voice-over narration, and the 1997 British film Nil by Mouth, in which the word was used 428 times.[37] The record has since been topped by Swearnet: The Movie, which says the word 935 times.[41]

The film's distributor in the United Arab Emirates cut some 45 minutes off the runtime to delete explicit scenes of swearing, religious profanity, drug use, and sex, and "muted" dialogue containing expletives. The National reported that filmgoers in the UAE believed the film should not have been shown rather than being edited so heavily.[42]

Release[]

Theatrical[]

The Wolf of Wall Street premiered at the Ziegfeld Theatre in New York City on December 17, 2013,[43] followed by a wide release on December 25, 2013. The film's original release date of November 15 was pushed back after cuts were made to reduce the runtime.[44] On October 22, 2013, it was reported that the film was set for release that Christmas.[45] On October 29, Paramount officially confirmed that the film would release on Christmas Day, with a running time of 165 minutes.[46][47] This runtime was changed to 179 minutes on November 25.[48] It was officially rated R by the Motion Picture Association for "sequences of strong sexual content, graphic nudity, drug use and language throughout, and for some violence".[49] In the UK, the film received an 18 certificate from the British Board of Film Classification for "very strong language, strong sex [and] hard drug use".[1]

The film is banned in Malaysia, Nepal, Zimbabwe, and Kenya because of its scenes depicting sex, drugs, and excessive use of profanity, and additional scenes have been cut in the versions playing in India. In Singapore, after cuts were made to an orgy scene as well as some religiously profane or denigrating language, the film was passed R21.[50][51]

The release of The Wolf of Wall Street marked a shift in cinema history when Paramount became the first major studio to distribute movies to theaters in digital format, eliminating 35mm film entirely. Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues was the last Paramount production to include a 35mm film version, while The Wolf of Wall Street was the first major movie distributed entirely digitally.[52][53]

Home media[]

The Wolf of Wall Street was released on DVD and Blu-ray on March 25, 2014.[54] On January 27, 2014, it was revealed that a four-hour director's cut would be attached to the home release.[55] It was later revealed by Paramount Pictures and Red Granite Pictures that the home release would feature only the theatrical release.[56]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The Wolf of Wall Street grossed $116.9 million in North America and $275.1 million internationally, for a total gross of $392 million,[2] making it Scorsese's highest-grossing film worldwide.[57] In North America, the film opened at number five in its first weekend, with $19.4 million in 3,387 theaters, behind The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, Frozen, Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues, and American Hustle.[58] In Australia, it is the highest grossing R-rated film, earning $12.96 million.[59]

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 79% based on 286 reviews and an average rating of 7.80/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Funny, self-referential, and irreverent to a fault, The Wolf of Wall Street finds Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio at their most infectiously dynamic."[60] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 75 out of 100 based on 47 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[61]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone magazine named The Wolf of Wall Street as the third best film of 2013, behind 12 Years a Slave and Gravity at numbers one and two, respectively.[62] The movie was chosen as one of the top ten films of the year by the American Film Institute.[63] Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle said "it is the best and most enjoyable American film to be released this year."[64] The Chicago Sun-Times's Richard Roeper gave the film a "B+" score, saying the film was "good, not great Scorsese".[65]

Dana Stevens of Slate was more critical labeling the film "epic in size, claustrophobically narrow in scope."[66] Marshall Fine of The Huffington Post argued that the story "wants us to be interested in characters who are dull people to start with, made duller by their delusions of being interesting because they are high".[67] Some critics viewed the film as an irresponsible glorification of Belfort and his associates rather than a satirical takedown. DiCaprio defended the film, arguing that it does not glorify the excessive lifestyle it depicts.[68][69]

In 2016, the film was ranked #78 on the BBC's 100 Greatest Films of the 21st Century list.[70] In June 2017, Richard Brody of The New Yorker named The Wolf of Wall Street as the second best film of the 21st century so far, behind Jean-Luc Godard's In Praise of Love.[71] In 2019, Brody named The Wolf of Wall Street the best film of the 2010s.[72]

Audience response[]

The film received an average grade of "C" on an A+ to F scale from audiences surveyed by CinemaScore,[73] the lowest rating of any film opening that week.[74] The Los Angeles Times argues that the film attracted conservative viewers by depicting a more moral tone in its marketing than the film itself depicted.[75]

Christina McDowell, daughter of Tom Prousalis, who worked closely with the real-life Belfort at Stratton Oakmont, wrote an open letter addressing Scorsese, DiCaprio, and Belfort himself, criticizing the film for insufficiently portraying the victims of the financial crimes created by Stratton Oakmont, for disregarding the damage that was done to her family as a result, and for giving celebrity status to persons (Belfort and his partners, including her father) who do not deserve it.[76]

Steven Perlberg of Business Insider saw an advance screening of the film at a Regal Cinemas near the Goldman Sachs building, with an audience of financial workers. Perlberg reported cheers from the audience at what he considered to be all the wrong moments, stating, "When Belfort — a drug addict attempting to remain sober — rips up a couch cushion to get to his secret coke stash, there were cheers."[77]

Former Assistant United States Attorney Joel M. Cohen, who prosecuted the real Belfort, criticized both the film and the book on which it is based. He said that he believes some of Belfort's claims were "invented", as for instance "[Belfort] aggrandized his importance and reverence for him by others at his firm." He strongly criticized the film for not depicting the "thousands of [scam] victims who lost hundreds of millions of dollars", not accepting the filmmakers' argument that it would have diverted attention from the wrongdoers. He deplored the ending—"beyond an insult" to Belfort's victims—in which the real Belfort appears, while showing "a large sign advertising the name of Mr. Belfort's real motivational speaking company", and a positive depiction of Belfort uttering "variants of the same falsehoods he trained others to use against his victims".[78]

Top ten lists[]

The Wolf of Wall Street was listed on many critics' top ten lists.[79]

- 1st – Sasha Stone, Awards Daily

- 1st – Stephen Schaefer, Boston Herald

- 1st – Richard Brody, The New Yorker (tied with To the Wonder)

- 2nd – Wesley Morris, Grantland

- 2nd – Mick LaSalle, San Francisco Chronicle

- 2nd – Ben Kenigsberg, The A.V. Club

- 3rd – James Berardinelli, Reelviews

- 3rd – MTV

- 3rd – Glenn Kenny, RogerEbert.com

- 3rd – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

- 4th – Scott Feinberg, The Hollywood Reporter

- 4th – Drew McWeeny, HitFix

- 4th – Yahoo! Movies

- 4th – Christopher Orr, The Atlantic

- 4th – Barbara Vancheri, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

- 5th – Caryn James, Indiewire[80]

- 5th – Stephen Holden, The New York Times

- 5th – Rex Reed, The New York Observer

- 5th – Katey Rich, Vanity Fair

- 5th – David Chen, /Film

- 6th – TV Guide

- 7th – Matt Zoller Seitz, RogerEbert.com[81]

- 7th – Film School Rejects

- 7th – Todd McCarthy, The Hollywood Reporter

- 7th – Scott Tobias, The Dissolve

- 7th – Scott Mantz, Access Hollywood

- 7th – Mark Mohan, The Oregonian

- 7th – Sam Adams, The A.V. Club

- 8th – Nathan Rabin, The Dissolve

- 8th – Bill Goodykoontz, Arizona Republic

- 8th – Randy Myers, San Jose Mercury News

- 9th – Joe Neumaier, New York Daily News

- 10th – Andrew O'Hehir, Salon.com

- 10th – Jessica Kiang and Katie Walsh, Indiewire

- 10th – A.O. Scott, The New York Times

- 10th – Rene Rodriguez, Miami Herald

- 10th – Marjorie Baumgarten, Austin Chronicle

- 10th – Keith Uhlich, Time Out New York

- Top 10 – (unranked top 10 lists)

- Top 10 – James Verniere, Boston Herald

- Top 10 – Stephen Whitty, The Star-Ledger

- Top 10 – Joe Williams, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Controversies[]

Use of animals[]

The Wolf of Wall Street uses animals including a chimpanzee, a lion, a snake, a fish, and dogs.[82] The chimpanzee and the lion were provided by the Big Cat Habitat wildlife sanctuary in Sarasota County, Florida. The four-year-old chimpanzee Chance spent time with actor Leonardo DiCaprio and learned to roller skate over the course of three weeks. The sanctuary also provided a lion named Handsome because the trading company depicted in the film used a lion as its symbol.[83] Danny Porush denied that there were any animals in the office, although he admitted to eating an employee's goldfish.[84]

In December 2013, prior to the film's premiere, the organization Friends of Animals criticized the use of the chimpanzee and organized a boycott of the film. Variety reported, "Friends of Animals thinks the chimp ... suffered irreversible psychological damage after being forced to act."[85] The Guardian commented on the increasing criticism of Hollywood's use of animals, stating that "The Wolf of Wall Street's use of a chimpanzee arrives as Hollywood comes under ever-increasing scrutiny for its employment of animals on screen". PETA also launched a campaign to highlight mistreatment of ape "actors" and to petition for DiCaprio not to work with great apes.[84]

Alleged 1MDB connection and subsequent Red Granite lawsuit[]

The film was alleged by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) to have been financed by money stolen from the Malaysian 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) sovereign wealth fund by producer Riza Aziz, who pled not guilty to charges laid in July 2019.[86] The film is part of a broader investigation into these illicit monetary movements, and, in 2016, was named in a series of civil complaints filed by the United States Department of Justice "for having provided a trust account through which hundreds of millions of dollars belonging to the 1MDB fund were illicitly siphoned".[87][88][89] To settle the civil lawsuit, Red Granite Pictures agreed to pay US$60 million to the U.S. government with no "admission of wrongdoing or liability on the part of Red Granite".[90] This settlement was part of a more expansive U.S. effort to seize approximately $1.7 billion in assets allegedly purchased with funds embezzled from 1MDB.[90] In January 2020, Belfort sued Red Granite for $300 million, also wishing to void his rights deal; he said that he would never have sold the rights to the production company if he had known where the film was being financed from.[91][92]

Thematic controversy and debate[]

Various scholars and individuals have criticized the film as materialistic, encouraging greedy behavior, extreme wealth, and advocating for the infamous individuals portrayed in the film. Christina McDowell, whose father, Tom Prousalis, worked in association with Jordan Belfort, accused the filmmakers of "exacerbating our national obsession with wealth and status and glorifying greed and psychopathic behavior". She continues to emphasize the gravity and timely significance of Belfort's crimes stating that Wolf of Wall Street is a "reckless attempt at continuing to pretend that these sorts of schemes are entertaining, even as the country is reeling from yet another round of Wall Street scandals".[93]

In response to Leonardo DiCaprio defending himself from criticism, Variety journalist Whitney Friedlander describes the film as "still three hours of cash, drugs, hookers, repeat". Friedlander argues that the film is a "celebration of this lifestyle" and argues that short-lived extreme wealth and extraordinary experiences are superior to a societally normal behavior.[94]

There are also those like Nikole TenBrink, vice president of marketing and membership at Risk and Insurance Management Society, who believes that the film is a "cautionary tale of what can happen when fraud is left unchecked". She describes Belfort's business acumen, his talent in communicating and selling his ideas, and his ability to motivate others as offering "valuable lessons for risk professionals as they seek to avoid similar pitfalls".[95]

Jordan Belfort's reception[]

In an interview on London Real, Jordan Belfort commented on the film's depiction of himself and of Stratton Oakmont. In this interview, Belfort mentions that the film did an excellent job at describing the "overall feeling" of those years, stating that "the camaraderie, the insanity, that was accurate". Regarding his use of drugs, Belfort mentions that his actual habits were "much worse" than what is depicted in the film, stating that he was "on 22 different drugs at the end".[96]

Belfort also analyzes the major inaccuracies regarding the film's oversimplification of Stratton Oakmont's gradual transition from advocating for "speculative stocks" in order to "help build America" to committing crimes. During the interview, Belfort expresses that he "didn't like hearing" overly simplified and blunt depictions of his crimes because "it made me look like I was just trying to rip people off". While unhappy with these practices, Belfort does acknowledge the cinematic benefits of these oversimplifications as "a very easy way in three hours" to "move the audience emotionally".[96]

Accolades[]

The film was nominated for five Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Director for Scorsese, Best Adapted Screenplay for Winter, Best Actor for DiCaprio, and Best Supporting Actor for Hill.[97] It was also nominated for four BAFTAs, including Best Director, Best Actor and Best Adapted Screenplay, and two Golden Globe Awards, including Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[98] DiCaprio won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy.[99]

Soundtrack[]

| The Wolf of Wall Street: Music from the Motion Picture | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various artists | |

| Released | December 17, 2013 (Digital download) |

| Length | 56:30 |

| Label | Virgin Records |

The soundtrack to The Wolf of Wall Street features both original and existing music tracks. It was released on December 17, 2013, for digital download.[100][101]

More than sixty songs were used in the film, but only sixteen were included on the official soundtrack. Notably, among the exceptions are original compositions by Theodore Shapiro.[102]

| No. | Title | Artist(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy" | Cannonball Adderley | 5:11 |

| 2. | "Dust My Broom" | Elmore James | 2:53 |

| 3. | "Bang! Bang!" | Joe Cuba | 4:06 |

| 4. | "Movin' Out (Anthony's Song)" | Billy Joel | 3:29 |

| 5. | "C'est si bon" | Eartha Kitt | 2:58 |

| 6. | "Goldfinger" | Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings | 2:30 |

| 7. | "Pretty Thing" | Bo Diddley | 2:49 |

| 8. | "Moonlight in Vermont" (Live at the Pershing Lounge) | Ahmad Jamal | 3:10 |

| 9. | "Smokestack Lightning" | Howlin' Wolf | 3:07 |

| 10. | "Hey Leroy, Your Mama's Callin' You" | The Jimmy Castor Bunch | 2:26 |

| 11. | "Double Dutch" | Malcolm McLaren | 3:56 |

| 12. | "Never Say Never" | Romeo Void | 5:54 |

| 13. | "Meth Lab Zoso Sticker" | 7horse | 3:42 |

| 14. | "Road Runner" | Bo Diddley | 2:46 |

| 15. | "Mrs. Robinson" | The Lemonheads | 3:44 |

| 16. | "Cast Your Fate to the Wind" | Allen Toussaint | 3:19 |

| Total length: | 56:30 | ||

See also[]

- Scam 1992

- The Big Bull

- Boiler Room

- Gordon Gekko

- Microcap stock fraud

- List of films that most frequently use the word "fuck"

References[]

- ^ a b "The Wolf of Wall Street (18)". British Board of Film Classification. December 12, 2013. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on March 23, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ "The Triumph of Digital Will Be the Death of Many Movies - History". The New Republic. newrepublic.com. September 12, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ "2013 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 5, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Buchanan, Kyle (December 26, 2013). "How Spike Jonze Ended Up in The Wolf of Wall Street". Vulture. Archived from the original on December 29, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ Charlie Gasparino (March 12, 2013). "'Wolf of Wall Street' Gets $1M Pay Day for Movie Rights". Fox Business. Archived from the original on February 17, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ a b Saravia, Jerry (June 5, 2013). "Raging Bull of Cinema Part II". Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ Pamela McClintock (March 25, 2007). "Scorsese, DiCaprio cry 'Wolf'". Variety. Archived from the original on October 26, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike. "Ridley Scott Eyeing Reteam With Leo DiCaprio On 'The Wolf Of Wall Street'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike. "Cannes: Red Granite Acquires Leonardo DiCaprio Pic 'The Wolf Of Wall Street'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Schilling, Mary Kaye (August 25, 2013). "Leonardo DiCaprio and Martin Scorsese Explore the Funny Side of Financial Depravity in The Wolf of Wall Street". Vulture. Archived from the original on December 1, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "OSCARS Q&A: 'Wolf Of Wall Street' Producer Emma Tillinger Koskoff On 'Sexy, Scary, Infuriating' Pic". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Cieply, Michael; Barnes, Brooks. "Strong Profit Margin at Paramount Pictures Underlines a Hollywood Shift". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "'The Wolf of Wall Street' Secures Overseas Distribution in Multiple Territories Through Universal". TheWrap. November 8, 2012. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ "The Untold Stories of The WOLF OF WALL STREET, Jordan Belfort – IMPAULSIVE EP. 81". Archived from the original on May 19, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Jordan Belfort Shares the Most Disgusting Story from His life (Not in wolf of wall street)". Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ Belfort, Jordan (October 24, 2016). The Wolf of Wall Street Collection: The Wolf of Wall Street & Catching the Wolf of Wall Street. ISBN 9781473657311. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ "Real 'Wolf of Wall Street' exec's son slams movie's 'inaccurate' characterization of his father". New York Daily News. December 19, 2013. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ Dockterman, Eliana (December 26, 2013). "The Wolf of Wall Street: The True Story". Time. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ Napier, Jim. "Kyle Chandler Joins Martin Scorsese's THE WOLF OF WALL STREET". GeekTyrant. Geektyrant Industries LLC. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ^ Paur, Joey. "Jon Favreau Joins Martin Scorsese's THE WOLF OF WALL STREET". GeekTyrant. Geektyrant Industries LLC. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ^ "Excerpt of 'The Wolf of Wall Street'". USA Today. October 12, 2007. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ Dungan, Isabelle. "The Real Wolf of Wall Street". YouTube. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ Peyser, Andrea (December 9, 2013). "'Wolf of Wall Street' can't shake Queens roots". New York Post. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ "Ankle injury made Julie Andrews miss Wolf Of Wall Street". The Times of India. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- ^ Thompson, Arienne (January 22, 2014). "Jonah Hill made just $60K for 'Wolf of Wall Street'". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Hilary (January 22, 2014). "Jonah Hill Says He Was Paid $60K for 'The Wolf of Wall Street' (Audio)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 24, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Cavan Sieczkowski (January 22, 2014). "Jonah Hill Paid Paltry $60,000 For 'Wolf Of Wall Street'". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on January 25, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Berov, David (August 7, 2012). "Screenwriter Terence Winter Talks The Wolf Of Wall Street". After the Cut. Archived from the original on September 6, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ Hill, Jonah (September 4, 2012). "Jonah Hill announces completion of first day of shooting Wolf of Wall Street". Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Simone, Stephanie (September 13, 2012). "Leo and crew converge on Closter for latest Martin Scorsese film". North Jersey Media Group. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Doughherty, Mike (October 30, 2020). "NY country club used to shoot 'The Wolf of Wall Street' and 'Red Oaks' could be taken by eminent domain". Golfweek. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "Jonah Hill 'hospitalised' after snorting so much fake cocaine on Wolf of Wall Street". independent.co.uk. May 31, 2019.

- ^ a b de Semlyen, Phil (June 27, 2012). "Scorsese Goes Digital, Abandons Film". Empire. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ a b Goldman, Michael (December 2013). "Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC and Martin Scorsese discuss their approach to The Wolf of Wall Street, the true story of a stockbrocker (sic) run amok". American Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ Bennett, Neil (September 20, 2013). "Interview: The Wolf of Wall Street's VFX producer". Digitalartsonline.co.uk. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ a b Thorne, Dan (January 16, 2014). "How The Wolf of Wall Street broke movie swearing record". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Forrest Wickman (January 7, 2014). "Is Wolf of Wall Street Really the Sweariest Movie of All Time? A Slate Investigation". Slate. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "The Wolf of Wall Street Breaks Profanity Record". Junkie Monkeys. December 29, 2013. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ Adam Holz (January 12, 2014). "Review: The Wolf of Wall Street". Plugged In. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014.

a handful more than 525 are f-words

- ^ Goldstein, Gary (September 25, 2014). "Review: 'Swearnet: The Movie'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

The f-bomb is unleashed a reported 935 times

- ^ Sinclair, Kyle (January 12, 2014). "Cinema fans question whether Scorsese movie should have been screened". The National. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Morfoot, Addie (December 18, 2013). "Terence Winter: Leo 'Brave Enough' for Candle Scene in 'Wolf of Wall Street'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (November 27, 2013). "Wolf of Wall Street Avoids NC-17 After Sex Cuts". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 9, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Brevet, Brad (October 22, 2013). "Scorsese's 'Wolf of Wall Street' Will Open on Christmas Day". Rope of Silicon. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (October 28, 2013). "It's Official: Martin Scorsese's 'Wolf of Wall Street' Gets Holiday Release". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (October 29, 2013). "Scorsese's 'Wolf of Wall Street' Will Open on Christmas Day". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (November 25, 2013). "THE WOLF OF WALL STREET Could Be Martin Scorsese's Longest Film Yet at 179 Minutes; 3 New Posters Released". Collider. Archived from the original on November 28, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Wolf of Wall Street Official Trailer". Paramount Pictures. YouTube. June 16, 2013. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ "Gay Orgy, Gone! 'Wolf of Wall Street' Censored, Banned Overseas". MovieThatMatters. Archived from the original on January 30, 2014.

- ^ Capital lifestyle (January 16, 2014). "Martin Scorsese's 'The Wolf of Wall Street' banned in Kenya". Capital Lifestyle. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Geuss, Megan (January 18, 2014). "Anchorman 2 was Paramount's final release on 35 mm film". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on January 21, 2014. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ Verrier, Richard (January 17, 2014). "End of film: Paramount first studio to stop distributing film prints". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "The Wolf of Wall Street Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Lee, Ann (January 28, 2014). "The Wolf of Wall Street DVD will be 4 hours long with more sex and swearing". Metro. Archived from the original on February 14, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (January 29, 2014). "THE WOLF OF WALL STREET Blu-ray/DVD May Include an Extended Cut with an Extra Hour of Sex and Swearing [UPDATED]". Collider. Archived from the original on February 17, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ "Box-Office Milestone: 'Wolf of Wall Street' Becomes Martin Scorsese's Top-Grossing Film". The Hollywood Reporter. February 11, 2014. Archived from the original on January 24, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 27–29, 2013". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ "The Wolf of Wall Street sets Australian record for an R-rated film". Smh.com.au. February 6, 2014. Archived from the original on June 7, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ "The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 10, 2013). "10 Best Movies of 2013". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "10 Outstanding Motion Pictures and Television Programs Inducted into the AFI Almanac of the Art Form". American Film Institute. December 9, 2013. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Mick LaSalle (December 24, 2013). "'Wolf of Wall Street' review: Scorsese right on the money". SFGate. Archived from the original on February 6, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "The Wolf of Wall Street". RichardRoeper.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Stevens, Dana (December 23, 2013). "The Wolf of Wall Street". Slate. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ Fine, Marshall (December 22, 2013). "Movie Review: The Wolf of Wall Street". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Leonardo DiCaprio Defends 'Wolf of Wall Street' Amid Controversy". MovieThatMatters.com. December 31, 2013. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Zagano, Phyllis (January 1, 2014). "The 'culture of prosperity'". National Catholic Reporter. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ Brody, Richard (June 12, 2017). "My Twenty-Five Best Films of the Century So Far". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 26, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Brody, Richard (November 26, 2019). "The Twenty-Seven Best Movies of the 2010s". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 17, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ "3 Obvious Reasons Why Audiences Hate The Wolf Of Wall Street". CinemaBlend. December 27, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Katey Rich (December 26, 2013). "The Wolf of Wall Street Is Enraging Moviegoers, Thrilling Bankers, And Making Tons Of Cash". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Steven Zeitchik (December 26, 2013). "'The Wolf of Wall Street:' Is it too polarizing for the mainstream? (2013)". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ Christina McDowell (December 26, 2013). "An Open Letter to the Makers of The Wolf of Wall Street, and the Wolf Himself". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ "Banker Pros Cheer At Wolf Of Wall Street". Business Insider. December 19, 2013. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Cohen, Joel M. (January 7, 2014). "The Real Belfort Story Missing From 'Wolf' Movie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ "2013 Film Critics Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. December 8, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ James, Caryn (December 20, 2013). "Best Films of 2013". Indiewire. Archived from the original on September 27, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Top Ten Lists of 2013 From Our Contributors". RogerEbert.com. January 1, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Tadeo, Maria (December 16, 2013). "Chimpanzee dressed in a suit roller-skating through prostitutes and dwarves in Wolf of Wall Street prompts boycott calls". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Cummings, Ian (December 26, 2013). "Sarasota chimp and lion have roles in 'Wolf of Wall Street'". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Child, Ben (December 16, 2013). "Scorsese's The Wolf of Wall Street: animal rights group calls for boycott". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Khatchatourian, Maane (December 13, 2013). "Animal Rights Group Boycotting 'Wolf of Wall Street'". Variety. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "Najib's stepson Riza Aziz charged with laundering $248m 1MDB money". Malay Mail. July 6, 2019. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Busch, Patrick Hipes, Anita (September 15, 2017). "Red Granite Settles With U.S. Government Over 2 Films As Part Of 1MDB Case". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ Hope, Bradley; Fritz, John R. Emshwiller And Ben (April 1, 2016). "The Secret Money Behind 'The Wolf of Wall Street'". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Pagliery, Jose (July 20, 2016). "Feds want 'Wolf of Wall Street' profits as part of $3.5 billion fraud allegations". CNN Money. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- ^ a b "'The Wolf of Wall Street' producers to pay $60 million to U.S. in..." Reuters. March 7, 2018. Archived from the original on November 2, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ El-Mahmond, Sarah (January 23, 2020). "The Wolf Of Wall Street Just Can't Catch A Break On Lawsuits". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Cullins, Ashley (January 23, 2020). "'Wolf of Wall Street' Inspiration Jordan Belfort Files $300M Fraud Lawsuit Against Red Granite". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Child, Ben (December 30, 2013). "The Wolf of Wall Street criticised for 'glorifying psychopathic behaviour'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ Friedlander, Whitney (December 31, 2013). "Does 'Wolf of Wall Street' Glorify Criminals? Yes". Variety. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ TenBrink, Nikole (March 2014). "Learning from the Wolf of Wall Street". Risk Management. 61 (2): 16. ProQuest 1506142048.

- ^ a b WHAT WAS REAL VS FICTION IN THE MOVIE WOLF OF WALL STREET – Jordan Belfort | London Real, retrieved December 15, 2019

- ^ "2014 Oscar Nominees". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. March 24, 2021. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Bafta Film Awards 2014: Full list of nominees". BBC News. January 8, 2014. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "Golden Globes 2014: Leonardo DiCaprio wins Best Actor for The Wolf of". The Independent. January 13, 2014. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (December 11, 2013). "'The Wolf Of Wall Street' Soundtrack Features The Lemonheads, Billy Joel & More Plus 2 New TV Spots And Poster". IndieWire. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Appelo, Tim (December 25, 2013). "Scorsese's Music Man on 'Wolf of Wall Street' Soundtrack Album: 'Marty is Fearless'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin. "All The Songs In 'The Wolf Of Wall Street' Including Devo, Cypress Hill, Foo Fighters & More". Indiewire. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Wolf of Wall Street (2013 film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Wolf of Wall Street (2013 film). |

- 2013 films

- English-language films

- 2010s biographical films

- 2013 black comedy films

- 2010s business films

- 2010s legal films

- American black comedy films

- American business films

- American films

- American legal films

- Fiction with unreliable narrators

- Films about drugs

- Biographical films about fraudsters

- Biographical films about businesspeople

- Films about financial crises

- Films directed by Martin Scorsese

- Films produced by Leonardo DiCaprio

- Comedy films based on actual events

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films featuring a Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films set in Italy

- Films set in the Las Vegas Valley

- Films set in London

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in New Zealand

- Films set in Switzerland

- Films set in the 1990s

- Films shot in New Jersey

- Films shot in New York (state)

- Films shot in New York City

- Appian Way Productions films

- Wall Street films

- Red Granite Pictures films

- Films about con artists

- Self-reflexive films

- 2010s English-language films

- Trading films

- Films about the upper class

- Films about narcissism

- Films produced by Martin Scorsese

- Cultural depictions of business people

- Cultural depictions of fraudsters

- Cultural depictions of American men

- Films banned in Nepal

- Works involved in a lawsuit

- Films set in 1991

- Films set in 1987

- Films set in 1989

- Films set in 1993

- Films set in 1996

- Films set in 1998

- Films about the Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Fictional portrayals of the New York City Police Department

- Paramount Pictures films