Theophanes the Cretan

Theophanes Bathas | |

|---|---|

Virgn & Child | |

| Born | 1485-1490 |

| Died | 1559 |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Known for | Painter |

| Movement | Cretan School |

Theophanis Strelitzas (Greek: Θεοφάνης Στρελίτζας 1490–1559), also known as Theophanes the Cretan (Θεοφάνης ὁ Κρής) pronounced Theophanes O Krees or Theophanes Bathas (Θεοφάνης Μπαθᾶς). He was a Greek painter and educator. He painted icons and frescos. He was a member of a prominent family of painters Strelitzas-Bathas. The origin of the family was the Peloponnesus region. His son was famous painter Symeon Bathas Strelitzas. He was also his apprentice. Other important painters of the same name were Thomas Bathas and Markos Bathas. Another fresco painter of the same period was Fragkos Katelanos. Theophanes's family built the framework of the Cretan School. Over one hundred icons and frescos have survived. They can be found all over Greece. Theophanes influenced countless painters. Some of the painters were Fragkos Katelanos and Dionysius of Fourna. He was one of the most important fresco painters of the period.[1][2][3]

History[]

Theophanes was born in Heraklion, Crete. He came from a long line of painters. His family was associated with painting for over one hundred years prior to his birth. They came from the Peloponnesus region. He was married and had two sons Symeon and Nifos-Neophytos. His wife died young. Theophanes decided to become a priest. He became a priest before 1527. Theophanes traveled to Mount Athos where he became a monk at the prominent monastery with his two sons. They both became monks and painters.[4]

He painted frescos in the largest monastery at Mount Athos. The Monastery of Great Lavra at Mount Athos. Theophanes had become so popular that he was entrusted with this very important task. He painted the frescos in the main building. It was a large Byzantine church founded in 1004. Theophanes's signature can be found in many parts of the building.[5]

In 1536, Theophanis purchased a seat in Great Lavra Monastery for him and his sons. In 1540, he gave more money to purchase a better location within the monastery. He obtained a vineyard and orchard. When his children were old enough he purchased the right for them to stay at the monastery with him. He also paid for his funeral in advance. Three years later Theophanes settled in Karyes. It was the administrative and commercial center of Mount Athos. He exchanged some of his property for a pyrgos or tower and meadows with orchards.[6]

Historians believe he traveled back and forth to Heraklion. They also agree Theophanis worked as a painter in Meteora at Saint Nicholas Monastery and Cyprus the Chrysostomou Monastery. By 1552, records indicate he was in Heraklion. He amassed a sizable fortune. He died the same day his will was recorded. He died on February 24, 1559. He gave his two children a sizable fortune consisting of gold coins, gold ducats, silver, and valuable gold byzantine coins. He also gave his children apartments in Heraklion.[7]

The Bathas family was a very important family in the world of icon painting. His sons continued his legacy. Other Bathas family members active around his life were Thomas Bathas, Markos Bathas and . Both Thomas Bathas and Markos Bathas traveled to Venice where they were active artists. Thomas Bathas became a very important figure in Venice. He was associated with Metropolitan of Philadelphia . Thomas Bathas also painted parts of the famous Greek-Italian church San Giorgio dei Greci.[8]

Notable Works[]

Frescos[]

- Narthex of the monastery of Agios Nikolaos Meteora

- Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos

- The Great Lavra Monastery Mount Athos

Icon Paintings[]

- Icon of Jesus Katholikon the Great Lavra Monastery Mount Athos

- Icon of Virgin Mary Katholikon the Great Lavra Monastery Mount Athos

- 11 Icons of the Dodekáorto (Twelve feasts of the Eastern Orthodox Church) Katholikon the Great Lavra Monastery Mount Athos

Gallery[]

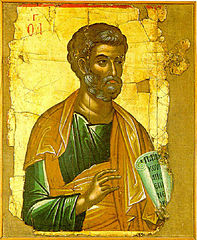

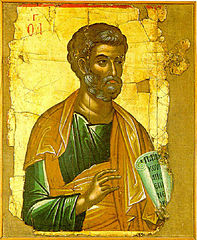

Apostle Peter - Stavronikita monastery, Mt Athos

Saint Paul 1546

Jesus in Golgotha

Crucifixion

Virgin and Child

The Ascension 1546

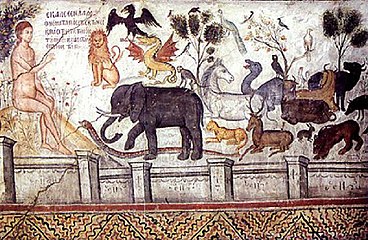

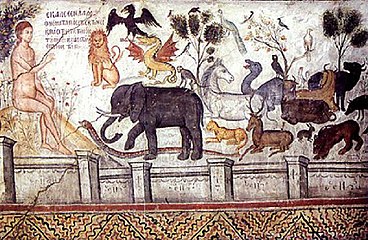

Adam naming the animals

Epitaphios (Lamentation of Christ) from Stavronikita monastery, Mount Athos.

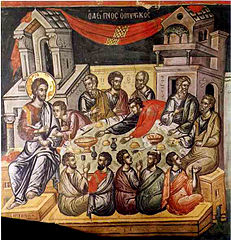

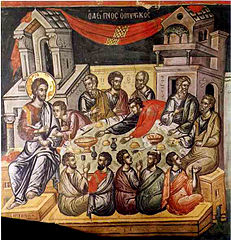

Last Supper, also from Stavronikita. Western influence is more apparent here, in the figures of the apostles especially.

Jesus and the Samaritan Woman

Saint Justin

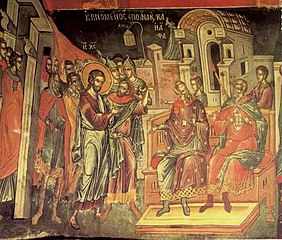

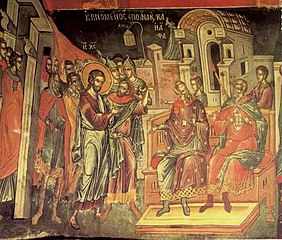

Jesus before Pontius Pilate

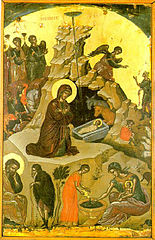

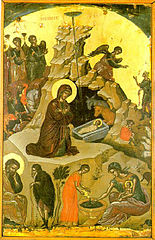

The Nativity Story

Prophet Ezekiel

Washing of the feet

St. John

References[]

- ^ Hatzidakis, Manolis & Drakopoulou, Eugenia (1997). Greek painters after the fall (1450-1830) Volume B (PDF). Center for Modern Greek Studies E.I.E. pp. 381–396.

- ^ Speake, Graham (2021). Encyclopedia of Greece and the Hellenic Tradition. London And New York: Rutledge Taylor & Francis Group. p. 1629-1630.

- ^ Eugenia Drakopoulou (June 28, 2021). "Strelitzas-Bathas Theofanis". Institute for Neohellenic Research. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Hatzidakis, 1997, pp 381-396

- ^ Hatzidakis, 1997, pp 381-396

- ^ Hatzidakis, 1997, pp 381-396

- ^ Hatzidakis, 1997, pp 381-396

- ^ Hatzidakis, 1997, pp 380-381

Bibliography[]

- Hatzidakis, Manolis (1987). Greek painters after the fall (1450-1830) Volume A. Center for Modern Greek Studies E.I.E.

- Hatzidakis, Manolis & Drakopoulou, Eugenia (1997). Greek painters after the fall (1450-1830) Volume B. Center for Modern Greek Studies E.I.E.

- Drakopoulou, Eugenia (2010). Greek painters after the fall (1450-1830) Volume C. Center for Modern Greek Studies E.I.E.

External links[]

- Byzantium: faith and power (1261-1557), an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Theophanes the Cretan

Media related to Theophanes the Cretan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Theophanes the Cretan at Wikimedia Commons- Article on his frescoes

- Theophanes of Crete in Byzantine art

- 1559 deaths

- Greek Christian monks

- Cretan Renaissance painters

- Artists from Heraklion

- Fresco painters

- Icon painters

- 16th-century Greek people

- 16th-century Greek painters