Thetis

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

|

| Greek deities series |

|---|

|

| Aquatic deities |

|

| Nymphs |

| Greek deities series |

|---|

|

| Aquatic deities |

|

Thetis (/ˈθiːtɪs/; Greek: Θέτις [tʰétis]), is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, or one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.[1]

When described as a Nereid in Classical myths, Thetis was the daughter of Nereus and Doris,[2] and a granddaughter of Tethys with whom she sometimes shares characteristics. Often she seems to lead the Nereids as they attend to her tasks. Sometimes she also is identified with Metis.

Some sources argue that she was one of the earliest of deities worshipped in Archaic Greece, the oral traditions and records of which are lost. Only one written record, a fragment, exists attesting to her worship and an early Alcman hymn exists that identifies Thetis as the creator of the universe. Worship of Thetis as the goddess is documented to have persisted in some regions by historical writers such as Pausanias.

In the Trojan War cycle of myth, the wedding of Thetis and the Greek hero Peleus is one of the precipitating events in the war which also led to the birth of their child Achilles.

As goddess[]

| Greek deities series |

|---|

|

| Nymphs |

Most extant material about Thetis concerns her role as mother of Achilles, but there is some evidence that as the sea-goddess she played a more central role in the religious beliefs and practices of Archaic Greece. The pre-modern etymology of her name, from tithemi (τίθημι), "to set up, establish," suggests a perception among Classical Greeks of an early political role. Walter Burkert[3] considers her name a transformed doublet of Tethys.

In Iliad I, Achilles recalls to his mother her role in defending, and thus legitimizing, the reign of Zeus against an incipient rebellion by three Olympians, each of whom has pre-Olympian roots:

You alone of all the gods saved Zeus the Darkener of the Skies from an inglorious fate, when some of the other Olympians – Hera, Poseidon, and Pallas Athene – had plotted to throw him into chains ... You, goddess, went and saved him from that indignity. You quickly summoned to high Olympus the monster of the hundred arms whom the gods call Briareus, but mankind Aegaeon,[4] a giant more powerful even than his father. He squatted by the Son of Cronos with such a show of force that the blessed gods slunk off in terror, leaving Zeus free

- — E.V. Rieu translation

Quintus of Smyrna, recalling this passage, does write that Thetis once released Zeus from chains; but there is no other reference to this rebellion among the Olympians, and some readers, such as M. M. Willcock,[5] have understood the episode as an ad hoc invention of Homer's to support Achilles' request that his mother intervene with Zeus. Laura Slatkin explores the apparent contradiction, in that the immediate presentation of Thetis in the Iliad is as a helpless minor goddess overcome by grief and lamenting to her Nereid sisters, and links the goddess's present and past through her grief.[6] She draws comparisons with Eos' role in another work of the epic Cycle concerning Troy, the lost Aethiopis,[7] which presents a strikingly similar relationship – that of the divine Dawn, Eos, with her slain son Memnon; she supplements the parallels with images from the repertory of archaic vase-painters, where Eos and Thetis flank the symmetrically opposed heroes, Achilles and Memnon, with a theme that may have been derived from traditional epic songs.[8]

Thetis does not need to appeal to Zeus for immortality for her son, but snatches him away to the White Island Leuke in the Black Sea, an alternate Elysium[9] where he has transcended death, and where an Achilles cult lingered into historic times.

Mythology[]

Thetis and the other deities[]

Pseudo-Apollodorus' Bibliotheke asserts that Thetis was courted by both Zeus and Poseidon, but she was married off to the mortal Peleus because of their fears about the prophecy by Themis[10] (or Prometheus, or Calchas, according to others) that her son would become greater than his father. Thus, she is revealed as a figure of cosmic capacity, quite capable of unsettling the divine order. (Slatkin 1986:12)

When Hephaestus was thrown from Olympus, whether cast out by Hera for his lameness or evicted by Zeus for taking Hera's side, the Oceanid Eurynome and the Nereid Thetis caught him and cared for him on the volcanic isle of Lemnos, while he labored for them as a smith, "working there in the hollow of the cave, and the stream of Okeanos around us went on forever with its foam and its murmur" (Iliad 18.369).

Thetis is not successful in her role protecting and nurturing a hero (the theme of kourotrophos), but her role in succoring deities is emphatically repeated by Homer, in three Iliad episodes: as well as her rescue of Zeus (1.396ff) and Hephaestus (18.369), Diomedes recalls that when Dionysus was expelled by Lycurgus with the Olympians' aid, he took refuge in the Erythraean Sea with Thetis in a bed of seaweed (6.123ff). These accounts associate Thetis with "a divine past—uninvolved with human events—with a level of divine invulnerability extraordinary by Olympian standards. Where within the framework of the Iliad the ultimate recourse is to Zeus for protection, here the poem seems to point to an alternative structure of cosmic relations"[11]

Marriage to Peleus[]

Zeus had received a prophecy that Thetis's son would become greater than his father, as Zeus had dethroned his father to lead the succeeding pantheon. In order to ensure a mortal father for her eventual offspring, Zeus and his brother Poseidon made arrangements for her to marry a human, Peleus, son of Aeacus, but she refused him.

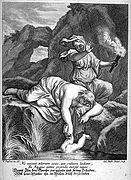

Proteus, an early sea-god, advised Peleus to find the sea nymph when she was asleep and bind her tightly to keep her from escaping by changing forms. She did shift shapes, becoming flame, water, a raging lioness, and a serpent.[12] Peleus held fast. Subdued, she then consented to marry him. Thetis is the mother of Achilles by Peleus, who became king of the Myrmidons.

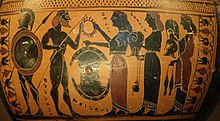

According to classical mythology, the wedding of Thetis and Peleus was celebrated on Mount Pelion, outside the cave of Chiron, and attended by the deities: there they celebrated the marriage with feasting. Apollo played the lyre and the Muses sang, Pindar claimed. At the wedding Chiron gave Peleus an ashen spear that had been polished by Athene and had a blade forged by Hephaestus. While the Olympian goddesses brought him gifts: from Aphrodite, a bowl with an embossed Eros, from Hera a chlamys while from Athena a flute. His father-in-law Nereus endowed him a basket of the salt called 'divine', which has an irresistible virtue for overeating, appetite and digestion, explaining the expression '...she poured the divine salt'. Zeus then bestowed the wings of Arce to the newly-wed couple which was later given by Thetis to her son, Achilles. Furthermore, the god of the sea, Poseidon gave Peleus the immortal horses, Balius and Xanthus.[13] Eris, the goddess of discord, had not been invited, however, and in spite, she threw a golden apple into the midst of the goddesses that was to be awarded only "to the fairest." In most interpretations, the award was made during the Judgement of Paris and eventually occasioned the Trojan War.

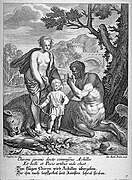

As is recounted in the Argonautica, written by the Hellenistic poet Apollonius of Rhodes, Thetis, in an attempt to make her son Achilles immortal, would burn away his mortality in a fire at night and during the day, she would anoint the child with ambrosia. When Peleus caught her searing the baby, he let out a cry.

Thetis heard him, and catching up the child threw him screaming to the ground, and she like a breath of wind passed swiftly from the hall as a dream and leapt into the sea, exceeding angry, and thereafter returned never again.

In a variant of the myth first recounted in the Achilleid, an unfinished epic written between 94–95 AD by the Roman poet Statius, Thetis tried to make Achilles invulnerable by dipping him in the River Styx (one of the five rivers that run through Hades, the realm of the dead). However, the heel by which she held him was not touched by the Styx's waters and failed to be protected. (A similar myth of immortalizing a child in fire is seen in the case of Demeter and the infant Demophoon). Some myths relate that because she had been interrupted by Peleus, Thetis had not made her son physically invulnerable. His heel, which she was about to burn away when her husband stopped her, had not been protected.

Peleus gave the boy to Chiron to raise. Prophecy said that the son of Thetis would have either a long but dull life, or a glorious but brief one. When the Trojan War broke out, Thetis was anxious and concealed Achilles, disguised as a girl, at the court of Lycomedes, king of Skyros. Achilles was already famed for his speed and skill in battle. Calchas, a priest of Agamemnon, prophesied the need for the great soldier within their ranks. Odysseus was subsequently sent by Agamemnon to try and find Achilles. Skyros was relatively close to Achilles’ home and Lycomedes was also a known friend of Thetis, so it was one of the first places that Odysseus looked. When Odysseus found that one of the girls at court was not a girl, he came up with a plan. Raising an alarm that they were under attack, Odysseus knew that the young Achilles would instinctively run for his weapons and armour, thereby revealing himself. Seeing that she could no longer prevent her son from realizing his destiny, Thetis then had Hephaestus make a shield and armor.

Iliad and the Trojan War[]

Thetis played a key part in the events of the Trojan War. Beyond the fact that the Judgement of Paris, which essentially kicked off the war, occurred at her wedding, Thetis influenced the actions of the Olympians and her son, Achilles.

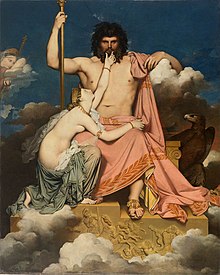

Nine years after the beginning of the Trojan War, Homer's Iliad starts with Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and the commander of the Achaeans, and Achilles, son of Thetis, arguing over Briseis, a war prize of Achilles. After initially refusing, Achilles relents and gives Briseis to Agamemnon. However, Achilles feels disrespect for having to give up Briseis and prays to Thetis, his mother, for restitution of his lost honor.[14] She urges Achilles to wait until she speaks with Zeus to rejoin the fighting, and Achilles listens.[15] When she finally speaks to Zeus, Thetis convinces him to do as she bids, and he seals his agreement with her by bowing his head, the strongest oath that he can make.[16]

Following the death of Patroclus, who wore Achilles' armor in the fighting, Thetis comes to Achilles to console him in his grief. She vows to return to him with armor forged by Hephaestus, the blacksmith of the gods, and tells him not to arm himself for battle until he sees her coming back. While Thetis is gone, Achilles is visited by Iris, the messenger of the gods, sent by Hera, who tells him to rejoin the fighting. He refuses, however, citing his mother's words and his promise to her to wait for her return.[17] Thetis, meanwhile, speaks with Hephaestus and begs him to make Achilles armor, which he does. First, he makes for Achilles a splendid shield, and having finished it, makes a breastplate, a helmet, and greaves.[18] When Thetis goes back to Achilles to deliver his new armor, she finds him still upset over Patroclus. Achilles fears that while he is off fighting the Trojans, Patroclus' body will decay and rot. Thetis, however, reassures him and places ambrosia and nectar in Patroclus' nose in order to protect his body against decay.[19]

After Achilles uses his new armor to defeat Hector in battle, he keeps Hector's body to mutilate and humiliate. However, after nine days, the gods call Thetis to Olympus and tell her that she must go to Achilles and pass him a message, that the gods are angry that Hector's body has not been returned. She does as she is bid, and convinces Achilles to return the body for ransom, thus avoiding the wrath of the gods.[20]

Worship in Laconia and other places[]

A noted exception to the general observation resulting from the existing historical records, that Thetis was not venerated as a goddess by cult, was in conservative Laconia, where Pausanias was informed that there had been priestesses of Thetis in archaic times, when a cult that was centered on a wooden cult image of Thetis (a xoanon), which preceded the building of the oldest temple; by the intervention of a highly placed woman, her cult had been re-founded with a temple; and in the second century AD she still was being worshipped with utmost reverence. The Lacedaemonians were at war with the Messenians, who had revolted, and their king Anaxander, having invaded Messenia, took as prisoners certain women, and among them Cleo, priestess of Thetis. The wife of Anaxander asked for this Cleo from her husband, and discovering that she had the wooden image of Thetis, she set up the woman Cleo in a temple for the goddess. This Leandris did because of a vision in a dream, but the wooden image of Thetis is guarded in secret.[21]

In one fragmentary hymn [22] by the seventh century Spartan poet, Alcman, Thetis appears as a demiurge, beginning her creation with poros (πόρος) "path, track" and tekmor (τέκμωρ) "marker, end-post". Third was skotos (σκότος) "darkness", and then the sun and moon. A close connection has been argued between Thetis and Metis, another shape-shifting sea-power later beloved by Zeus but prophesied bound to produce a son greater than his father because of her great strength.[23]

Herodotus[24] noted that the Persians sacrificed to "Thetis" at Cape Sepias. By the process of interpretatio graeca, Herodotus identifies a sea-goddess of another culture (probably Anahita) as the familiar Hellenic "Thetis" .

In other works[]

- Homer's Iliad makes many references to Thetis.

- Euripides's Andromache, 1232-1272

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica IV, 770–879.

- Bibliotheca 3.13.5.

- Francesco Cavalli's first opera Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo, composed in 1639, concerned the marriage of Thetis and Peleus

- WH Auden's poem The Shield of Achilles imagines Thetis's witnessing of the forging of Achilles's shield.

- In 1939, HMS Thetis (N25) then a new design of submarine, sank on her trials in the River Mersey shortly after she left the dock in Liverpool. There were 103 people on board and 99 died. The cause of the accident was an inspection hole to allow a sailor to look into the torpedo tubes. A special closure for this inspection hole had been painted over. Once submerged the torpedo tube flooded and the bow of the vessel sank. The stern was still above water. Ninety-nine people, half of them dockyard workers, died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

- In 1981, British actress Maggie Smith portrayed Thetis in the Ray Harryhausen film Clash of the Titans (for which she won a Saturn Award). In the film, she acts as the main antagonist to the hero Perseus for the mistreatment of her son Calibos.

- In 1999, British poet Carol Ann Duffy published The World's Wife poetry collection, which included a poem based on Thetis

- In 2004, British actress Julie Christie portrayed Thetis in the Wolfgang Petersen film Troy.

- In 2011, American novelist Madeline Miller portrayed Thetis in The Song of Achilles as a harsh and remote deity.

- The 2018 novel The Silence of the Girls focuses on the character of Briseis in the first person, with interjections giving Achilles' internal state of mind, including his tormented relationship with his mother.

Gallery[]

Thetis, Peleus and Zeus[]

Wedding of Peleus and Thetis[]

Thetis and Achilles[]

Notes[]

- ^ "Nereus: Sea-God, the Old Man of the Sea | Greek mythology, w/ pictures". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 240 ff.; her mother was Thalassa according to Lucian, Dialog of the Sea Gods, 11, 2.

- ^ Burkert, The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age, 1993, pp 92-93.

- ^ The "goatish one"

- ^ M. M. Willcock, (1977), "Ad Hoc Invention in the Iliad", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 81 pp. 41-53.

- ^ Slatkin, "The Wrath of Thetis" Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974)116 (1986), pp. 1-24.

- ^ The summary by Proclus survives.

- ^ "When Achilles fights with Memnon, the two divine mothers, Thetis and Eos, rush to the scene – this was probably the subject of a pre-Iliad epic song, and it also appears on one of the earliest mythological vase paintings." (Walter Burkert, Greek Religion 1985, p 121.

- ^ Erwin Rohde calls the isle of Leuke a sonderelysion in Psyche: Seelen Unsterblickkeitsglaube der Grieche (1898) 3:371, noted by Slatkin 1986:4note.

- ^ Pindar, Eighth Isthmian Ode.

- ^ Slatkin 1986:10.

- ^ Ovid:Metamorphoses xi, 221ff.; Sophocles: Troilus, quoted by scholiast on Pindar's Nemean Odes iii. 35; Apollodorus: iii, 13.5; Pindar: Nemean Odes iv .62; Pausanias: v.18.1

- ^ Photius, Bibliotheca 190.46. Translated by John Henry Freese, from the SPCK edition of 1920, now in the public domain, and other brief excerpts from subsequent sections translated by Roger Pearse (from the French translation by Rene Henry, ed. Les Belles Lettres)

- ^ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press. pp. 59–70. ISBN 978-0226470498.

- ^ introduction, Homer ; translated by Robert Fagles; Knox, notes by Bernard (2001). The Iliad ([Repr. with revisions]. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. p. 91. ISBN 0140275363.

- ^ introduction, Homer ; translated by Robert Fagles; Knox, notes by Bernard (2001). The Iliad ([Repr. with revisions]. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. p. 95. ISBN 0140275363.

- ^ introduction, Homer ; translated by Robert Fagles; Knox, notes by Bernard (2001). The Iliad ([Repr. with revisions]. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. pp. 472–474. ISBN 0140275363.

- ^ introduction, Homer ; translated by Robert Fagles; Knox, notes by Bernard (2001). The Iliad ([Repr. with revisions]. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. pp. 480–487. ISBN 0140275363.

- ^ introduction, Homer ; translated by Robert Fagles; Knox, notes by Bernard (2001). The Iliad ([Repr. with revisions]. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. p. 489. ISBN 0140275363.

- ^ introduction, Homer ; translated by Robert Fagles; Knox, notes by Bernard (2001). The Iliad ([Repr. with revisions]. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. pp. 592–593. ISBN 0140275363.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 3.14.4–5

- ^ The papyrus fragment was found at Oxyrhynchus.

- ^ M. Detienne and J.-P. Vernant, Les Ruses de l'intelligence: la métis des Grecs (Paris, 1974) pp. 127–64, noted in Slatkin 1986:14note.

- ^ Herodotus Histories 6.1.191.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thetis. |

- Thetis: very full classical references

- Slatkin: The Power of Thetis: a seminal work freely available in the University of California Press, eScholarship collection.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Greek goddesses

- Greek sea goddesses

- Nereids

- Nymphs

- Shapeshifting

- Women in Greek mythology

- Characters in Greek mythology

- Deities in the Iliad

- Deeds of Zeus

- Deeds of Poseidon

- Achilles

- Metamorphoses characters