This Island Earth

| This Island Earth | |

|---|---|

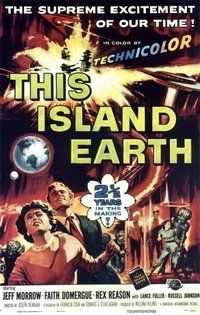

Theatrical release poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | This Island Earth 1952 novel by Raymond F. Jones |

| Produced by | William Alland |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Clifford Stine |

| Edited by | Virgil Vogel |

| Music by | (supervision) Uncredited: Henry Mancini Hans J. Salter Herman Stein |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal-International |

Release date |

|

Running time | 86 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $800,000 (estimated)[2] |

| Box office | $1.7 million[3] |

This Island Earth is a 1955 American science fiction film from Universal-International, produced by William Alland, directed by Joseph M. Newman and Jack Arnold, starring Jeff Morrow, Faith Domergue and Rex Reason. It is based on the eponymous 1952 novel by Raymond F. Jones, which was originally published in the magazine Thrilling Wonder Stories as three related novelettes: "The Alien Machine" in the June 1949 issue, "The Shroud of Secrecy" in December 1949, and "The Greater Conflict" in February 1950. The film was released in 1955 as a double feature with Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy.

Upon initial release, the film was praised by critics, who cited the special effects, well-written script, and eye-popping Technicolor prints as being its major assets.[4][5] In 1996, it was edited down and lampooned in Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie, a spin-off of the popular syndicated movie riffing television series Mystery Science Theater 3000. Scream Factory released the film on Blu-ray with a new 4K scan of the interpositive, featuring two aspect ratios: 1.85:1 and 1.37:1.[6]

Plot[]

Dr. Cal Meacham is flying to his laboratory in a borrowed Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star jet. Just before landing, the jet's engine fails, but he is saved from crashing by a mysterious green glow.

At the lab is an unusual substitute for the electronic condensers that he had ordered. Instead, he discovers instructions and parts to build a complex device called an "interocitor". Neither Meacham nor his assistant Joe Wilson have heard of such a device, but they immediately begin its construction. When they finish, a mysterious man named Exeter appears on the interocitor screen and informs Meacham that he has passed the test. His ability to build the interocitor demonstrates that he is gifted enough to be part of Exeter's special research project.

Intrigued, Meacham is picked up at the airport by an unmanned, computer-controlled Douglas C-47 aircraft with no windows. Landing in a remote area of Georgia, he finds an international group of top scientists already present, including an old flame, Dr. Ruth Adams. Cal is confused by Ruth's failure to recognize him and suspicious of Exeter, his assistant Brack and other odd-looking men leading the project.

Cal and Ruth flee with a third scientist, Steve Carlson, but their car is attacked and Carlson is killed. When they take off in a Stinson 108 light aircraft, Cal and Ruth watch as the facility and all its inhabitants are incinerated. Their aircraft is then drawn up by a bright beam into a flying saucer. Exeter explains that he and his men are from the planet Metaluna and are locked in a war with the Zagons. They defend against the Zagons with an energy field, but are running out of uranium to keep it running. They enlisted the humans in an effort to transmute lead to uranium, but time has run out. Exeter takes the Earthlings back to his world, sealing them in protective tubes to offset pressure differences between planets.

They land safely on Metaluna, but the planet is under attack by Zagon starships guiding meteors as weapons against them. The defensive "ionization layer" is failing, and the battle is entering its final stage. Metaluna's leader, the Monitor, reveals that the Metalunans intend to flee to Earth, then insists that Meacham and Adams be subjected to a Thought Transference Chamber in order to subjugate their free will, which he indicates will be the fate of the rest of humanity as well upon Metalunan relocation. Exeter believes that this is immoral and misguided.

Before the couple can be sent into the brain-reprogramming device, Exeter helps them escape. Exeter is badly injured by a Mutant while he, Cal and Ruth flee from Metaluna in the saucer, while the planet's ionization layer becomes totally ineffective. Under the Zagon bombardment, Metaluna heats up and turns into a lifeless "radioactive sun". The Mutant has also boarded the saucer and attacks Ruth, but dies as a result of pressure differences on the journey back to Earth.

As they enter Earth's atmosphere, Exeter sends Cal and Ruth on their way in their aircraft, declining an invitation to join them. Exeter is dying and the ship's energy is nearly depleted. The saucer flies out over the ocean and rapidly accelerates until it is enclosed in a fireball, crashes into the water, and explodes.

Cast[]

- Jeff Morrow as Exeter

- Faith Domergue as Ruth Adams

- Rex Reason as Cal Meacham

- Lance Fuller as Brack

- Russell Johnson as Steve Carlson

- Douglas Spencer as The Monitor

- Robert Nichols as Joe Wilson

- Orangey as Neutron the cat

Production[]

Principal photography for This Island Earth took place from January 30 to March 22, 1954. Location work took place at Mt. Wilson, California.[7] Most of the Metaluna sequence was directed by Jack Arnold; the front office was apparently dissatisfied with the footage Newman shot and had it redone by Arnold, who unlike Newman had several sci-fiction films to his credit.

Most of the sound effects, the ship, the interociter, etc. are simply recordings of radio teletype transmissions picked up on a short-wave radio played at various speeds. In a magazine article, the special effects department admitted that the "mutant" costume originally had legs that matched the upper body, but they had so much trouble making the legs look and work properly that they were forced by studio deadline to simply have the mutant wear a pair of trousers. Posters of the movie show the mutant as it was supposed to appear.

This title was one of the very few "flat widescreen" titles to be printed direct-to-matrix by Technicolor. This specially ordered 35-millimeter printing process was intended to maintain the highest possible print quality, as well as to protect the negative. Another film that was also given the direct-to-matrix treatment was Written on the Wind, which was also a Universal-International film.

Reception[]

Box-office[]

This Island Earth was released in June 1955,[8] and by the end of that year had accrued US$1,700,000 in distributors' domestic (United States and Canada) rentals, making it the year's 74th biggest earner.[9][N 1]

Critical response[]

A review in The New York Times by Howard Thompson stated: "The technical effects of This Island Earth, Universal's first science-fiction excursion in color, are so superlatively bizarre and beautiful that some serious shortcomings can be excused, if not overlooked."[4] "Whit" in Variety wrote: "Special effects of the most realistic type rival the story and characterizations in capturing the interest in this exciting science-fiction chiller, one of the most imaginative, fantastic and cleverly-conceived entries to date in the outer-space film field."[5] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times was also positive, calling it "one of the most fascinating — and frightening — science-fiction movies to come at us yet from outer space ... To the camera and effects men must go the major laurels for making this wonders visible and audible — in awesome Technicolor and a sound track that is as ear-wracking as it is eerie."[10] The Monthly Film Bulletin was less positive, writing: "Faced with the wonders of space, man's reactions prove, as usual, dreadfully limited. The dialogue—especially in the faked-up romance between Doctors Meacham and Adams—remains resolutely earth-bound, while the ending is simply a spacial variation on the conventional curtain. Joseph Newman has done his best to make his characters as intriguing as his special effects, but they have neither the stature nor the expression."[11]

Since its original release, the critical response to the film has continued to be mostly positive. Bill Warren has written that the film was "the best and most significant science fiction movie of 1955 … [it] remains a decent, competent example of any era's science fiction output".[8] In Phil Hardy's The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction, the film was described as "a full-blooded space opera complete with interplanetary warfare and bug-eyed monsters ... the film's space operatics are given a dreamlike quality and a moral dimension that makes the dramatic situation far more interesting".[12] Danny Peary felt that the film was "colorful, imaginative, gadget-laden sci-fi".[13] At the film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a score of 71%, based upon 14 reviews.[14] Greater Milwaukee Today described it as "an appalling film".[15]

In popular culture[]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

- Castle Films released a 9 to 12-minute (depending on projector speed) 8 mm cutting from the film (and retitled it War of the Planets) for the home movie audience, beginning in 1961.

- In Explorers (1985), one of the movies that Ben (played by Ethan Hawke) watches is This Island Earth. In that movie and this one, the character builds a device with help from an alien so that they may meet.

- A brief homage to This Island Earth is seen in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), E.T. turns the television on during a showing of the film, at the scene when Cal and Ruth are being abducted by the aliens and Cal says "They're pulling us up!"

- A segment of the television series Wonder Woman (season 2, episode 10, 1977) uses space battle footage from this, and the alien planet is also recycled footage.

- The album Happy Together (1987) by the a cappella group The Nylons featured a track titled "This Island Earth".[16]

- The video game Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders (1988) contains key references to this movie, such as large-headed aliens disguised as humans, communications through interstellar teleconferencing, and an aircraft pulled into a flying saucer.

- Shock rock metal band GWAR's fourth album, This Toilet Earth (1994), and its companion short-form movie Skulhedface contain numerous references to this movie, including the title, an alien with an oversized brain posing as a human, and communication between aliens using an interstellar teleconference device.

- New Jersey punk rock band The Misfits included a song tribute entitled "This Island Earth" on their album American Psycho (1997).

- The alien Orbitron, the Man from Uranus, from the 1960s toy line "The Outer Space Men", also known as Colorform Aliens, is based on the Mutant.

- A fan of This Island Earth, Weird Al Yankovic has featured the interocitor in both his film UHF (1989) and the music video for "Dare to be Stupid".

- The Metaluna Mutant is one of the many alien monsters held captive at Area 52 in Looney Tunes: Back in Action. It was later one of the aliens released by Marvin the Martian so that it could stop the main characters from taking the "Queen of Diamonds" card.

- Experimental pop artist Eric Millikin created a large mosaic portrait of the Metaluna Mutant out of Halloween candy and spiders as part of his "Totally Sweet" series in 2013.[17]

- This Island Earth is the film-within-the-film in Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie (or MST3K: The Movie). In order to maintain a 73-minute running time and to accommodate several "host segments", This Island Earth was edited down by about 20 minutes. Michael J. Nelson said that This Island Earth was chosen to mock because, he felt, "nothing really happens" and "it violates all the rules of classical drama". Kevin Murphy added that the film had many elements that the writing crew liked, such as "A hero who's a big-chinned white-guy scientist with a deep voice. A wormy sidekick guy. Huge-foreheaded aliens who nobody can quite figure out are aliens – there's just 'something different about them'. And a couple of rubber monsters who die on their own without the hero ever doing anything."[18]

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ "Rentals" refers to the distributor/studio's share of the box office gross, which, according to Gebert, is roughly half of the money generated by ticket sales.

Citations[]

- ^ "This Island Earth - Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ Internet Movie Database Box office/Business for

- ^ "The Top Box-Office Hits of 1955". Variety Weekly, January 25, 1956.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson, Howard H. "This Island Earth (1955) 'This Island Earth' Explored From Space." The New York Times, June 11, 1955.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Willis 1985, p. 107.

- ^ Tatlock, Michael (June 24, 2019). "This Island Earth Blu-ray Review (Scream Factory)". Cultsploitation. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ "Original print Information: This Island Earth (1955)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: October 30, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Warren 1982, pp. 228–234; 444.

- ^ Geber 1996.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (June 16, 1955) "Space Tale Fascinates, Frightens". Los Angeles Times. Part III, p. 10.

- ^ "This Island Earth". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 22 (257): 87. June 1955.

- ^ Hardy 1995.

- ^ Peary 1986, p. 433.

- ^ "This Island Earth (1955)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved: October 30, 2014.

- ^ Snyder, Steven. "This Island Earth Reviews". Greater Milwaukee Today, December 12, 2002. Retrieved: October 30, 2014.

- ^ Nylons – This Island Earth. January 2, 2012 – via YouTube.

- ^ Millikin, Eric. "Eric Millikin's totally sweet Halloween candy monster portraits". Detroit Free Press, December 9, 2013. Retrieved: October 30, 2014.

- ^ 'MST3K' Attacks a New Alien Force: Real Moviegoers.

Bibliography[]

- Gebert, Michael. The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards. New York: St. Martin's Paperbacks, 1996. ISBN 0-668-05308-9.

- Hardy, Phil (editor). The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction. London: Aurum Press, 1984. Reprinted as The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction, Overlook Press, 1995, ISBN 0-87951-626-7.

- Peary, Danny. Guide for the Film Fanatic. New York: Fireside Books, 1986. ISBN 0-671-61081-3.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching The Skies, Vol. I: 1950–1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

- Willis, Don. Variety's Complete Science Fiction Reviews. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1985. ISBN 0-8240-6263-9.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: This Island Earth |

- 1955 films

- English-language films

- 1950s monster movies

- 1950s science fiction films

- American films

- American monster movies

- American science fiction war films

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on science fiction novels

- Films directed by Joseph M. Newman

- Films scored by Henry Mancini

- Films scored by Hans J. Salter

- Films scored by Herman Stein

- Films set on fictional planets

- Universal Pictures films