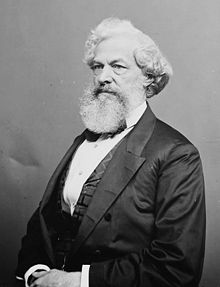

Thomas Ustick Walter

Thomas Ustick Walter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Architect of the Capitol | |

| In office June 11, 1851 – May 26, 1865 | |

| President | Millard Fillmore Franklin Pierce James Buchanan Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Charles Bulfinch |

| Succeeded by | Edward Clark |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 4, 1804 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died | October 30, 1887 (aged 83) Washington, D.C., US |

| Nationality | American |

| Profession | Civil Engineer |

Thomas Ustick Walter | |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Moyamensing Prison Girard College |

| Projects | United States Capitol dome Philadelphia City Hall |

Thomas Ustick Walter (September 4, 1804 – October 30, 1887) was an American architect of German descent, the dean of American architecture between the 1820 death of Benjamin Latrobe and the emergence of H.H. Richardson in the 1870s. He was the fourth Architect of the Capitol and responsible for adding the north (Senate) and south (House) wings and the central dome that is predominately the current appearance of the U.S. Capitol building. Walter was one of the founders and second president of the American Institute of Architects. In 1839, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[1]

Early life[]

Born in 1804 in Philadelphia, Walter was the son of mason and bricklayer Joseph S. Walter and his wife Deborah.[2] Walter was a mason's apprentice to his father. He also studied architecture and technical drawing at the Franklin Institute.

Walter received early training in a variety of fields including masonry, mathematics, physical science, and the fine arts. At 15, Walter entered the office of William Strickland, studying architecture and mechanical drawing,[2] then established his own practice in 1830.[3]

Works[]

Walter was commissioned by Spruce Street Baptist Church to design its new building at 418 Spruce Street in Philadelphia. The 1829 building is today home to the Society Hill Synagogue. Walter's first major commission was Moyamensing Prison, the Philadelphia County Prison. Designed as a humane model in its time, the prison was built between 1832 and 1835.[3] Walter also designed the First Presbyterian Church of West Chester, which opened its doors in January 1834.[4] In March 1834, the Walter-designed Wills Eye Hospital opened on the southwest corner of 18th and Race Streets in Philadelphia (on Logan Square).[5]

Walter first came to national recognition for his design of Girard College for Orphans (1833–1848) in Philadelphia, among the last and grandest expressions of the Greek Revival movement.[citation needed] Walter designed mansions, banks, churches, the hotel at Brandywine Springs, and courthouses.[6] In 1836, he designed the Bank of Chester County at West Chester, Pennsylvania.[7] In 1845, he was commissioned a decade later, he designed the 1846 Chester County Courthouse in Greek Revival style.[8] He designed the St. James Episcopal Church (Wilmington, North Carolina) which opened in 1840. In Lexington, Virginia, he designed the Lexington Presbyterian Church in 1843.[9] The same year he designed the Chapel of the Cross in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. In Norfolk, Virginia, he designed the Norfolk Academy in 1840.[10] The Tabb Street Presbyterian Church was erected at Petersburg, Virginia in 1843.[11] It has also been suggested that Walter designed the Second Empire-styled Quarters B and Quarters D at Admiral's Row in Brooklyn, New York.[citation needed]

Among the notable residences designed by Walter were his own home, located at High and Morton Streets in the Germantown section of Philadelphia,[12] the Nicholas Biddle estate Andalusia; Inglewood Cottage; and St. George's Hall, residence of Matthew Newkirk, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad (PW&B).[13] Walter also designed the Garrett-Dunn House in Philadelphia's Mt. Airy neighborhood,[14] which was destroyed by fire after being struck by lightning in 2009.[15] Among his smaller designs was the 1839 Newkirk Viaduct Monument, commissioned by the PW&B to mark the completion of the first rail line south from Philadelphia.[16]

The U.S. Capitol and its dome[]

The most famous of Walter's constructions is the dome of the U.S. Capitol. By 1850, the rapid expansion of the United States had caused a space shortage in the Capitol. Walter was selected to design extensions for the Capitol. His plan more than doubled the size of the existing building and added the familiar cast-iron dome.

There were at least six draftsmen in Walter's office, headed by Walter's chief assistant, August Schoenborn, a German immigrant who had learned his profession from the ground up. It appears that he was responsible for some of the fundamental ideas in the Capitol structure. These included the curved arch ribs and an ingenious arrangement used to cantilever the base of the columns. This made it appear that the diameter of the base exceeded the actual diameter of the foundation, thereby enlarging the proportions of the total structure.[17]

Construction on the wings began in 1851 and proceeded rapidly; the House of Representatives met in its new quarters in December 1857 and the Senate occupied its new chamber by January 1859. Walter's fireproof cast iron dome was authorized by Congress on March 3, 1855, and was nearly completed by December 2, 1863, when the Statue of Freedom was placed on top. The dome's cast iron frame was supplied and constructed by the iron foundry Janes, Fowler, Kirtland & Co.[18] He also reconstructed the interior of the west center building for the Library of Congress after the fire of 1851. Walter continued as Capitol architect until 1865, when he resigned his position over a minor contract dispute. After 14 years in Washington, he retired to his native Philadelphia.[citation needed]

In the 1870s, financial setbacks forced Walter to come out of retirement, and he worked as second-in-command when his friend and younger colleague John McArthur, Jr., won the design competition for Philadelphia City Hall. He continued on that vast project until his death in 1887. He was interred at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.[19]

Other honors[]

For their architectural accomplishments, both Walter and Benjamin Latrobe are honored in a ceiling mosaic in the East Mosaic Corridor at the entrance to the Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress.

Walter's grandson, Thomas Ustick Walter III, was also an architect; he practiced in Birmingham, Alabama, from the 1890s to the 1910s.[20]

Gallery[]

Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia. It was completed in 1835, and demolished in 1968.

One of Walter's first commissions, the First Presbyterian Church, West Chester, Pennsylvania, built 1832.

Lexington Presbyterian Church, Lexington, Virginia, built 1843–45.

Chester County Courthouse in West Chester.

First Baptist Church, Bristol, Pennsylvania

Mosaic in ceiling of Library of Congress, Washington, DC honoring Benjamin Henry Latrobe and Thomas Walter

Mosaic detail

Tabb Street Presbyterian Church, December 2009

Chester County Prison, built 1838, demolished 1960

Horticultural Hall - Former Opera House, Current Home of Chester County Historical Society.[21]

See also[]

- Old Patent Office Building

- 1877 U. S. Patent Office fire

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas U. Walter. |

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Frary, Ihna Thayer (1940). They Built the Capitol. Ayer Publishing. p. 201.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mason, Jr., George C. (1888). "Memoir". Proceedings of the ... Annual Convention of the American Institute of Architects. 21–22: 101–108.

- ^ Filemban, Mustafa. "WC History: The Shipwrecked Entrepreneur". www.downtownwestchester.com. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ Tasman, William (1980). The History of Wills Eye Hospital. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0061425318.

- ^ "Thomas Ustick Walter- Historic Architecture for a Modern World". Philaathenaeum.org. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ "Bank of Chester County, 17 North High Street, West Chester, Chester County, PA" (Searchable database). Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey, Engineering Record, Landscapes Survey Collection. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- ^ dsf.chesco.org Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine - Chester county courthouse West Chester, Pennsylvania

- ^ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (March 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Lexington Presbyterian Church" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ^ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (July 1969). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Norfolk Academy" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. and Accompanying photo

- ^ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (February 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Tabb Street Presbyterian Church" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ^ "Walter Residence". www.philadelphiabuildings.org. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ "St. George's Hall. [graphic]". The Library Company of Philadelphia. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ^ "Garrett Residence". www.philadelphiabuildings.org. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ "Garrett-Dunn House destroyed". WHYY. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ "Newkirk Monument". www.philadelphiabuildings.org. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ August Schoenborn at archINFORM

- ^ Terrell, Ellen (2015-05-20). "The Capitol Dome: Janes, Fowler, & Kirtland Co. | Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ Laurel Hill Cemetery

- ^ Fazio, Michael W. (2010) Landscape of Transformations: Architecture and Birmingham, Alabama. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press ISBN 978-1-57233-687-2

- ^ Lukens, Ph.D., Rob (December 11, 2011). "THOMAS U. WHO???". www.chestercohistorical.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-20. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

External links[]

- Aoc.gov file

- Brief biography of Thomas Ustick Walter

- Walter's drawings at the Atheneum of Philadelphia

- The Winterthur Library Overview of an archival collection on Thomas Ustick Walter.

- Library of Congress, Jefferson Building East Corridor mosaics

- Old Patent Office Building video

- 1804 births

- 1887 deaths

- Architects from Philadelphia

- Fellows of the American Institute of Architects

- American people of German descent

- Architects of the Capitol

- Greek Revival architects

- Presidents of the American Institute of Architects

- 19th-century American architects

- Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia)