Threshold host density

Threshold host density (NT), in the context of wildlife disease ecology, refers to the concentration of a population of a particular organism as it relates to disease. Specifically, the threshold host density (NT) of a species refers to the minimum concentration of individuals necessary to sustain a given disease within a population.[1]

Threshold host density (NT) only applies to density dependent diseases, where there is an "aggregation of risk" to the host in either high host density or low host density patches. When low host density causes an increase in incidence of parasitism or disease, this is known as inverse host density dependence, whereas when incidence of parasitism or disease is elevated in high host density conditions, it is known as direct host density dependence.

Host density independent diseases show no correlation between the concentration of a given host population and the incidence of a particular disease. Some examples of host density independent diseases are sexually transmitted diseases in both humans and other animals. This is due to the constant incidence of interaction observed in sexually transmitted diseases—even if there are only 20 individuals left of a given population, survival of the species requires sexual contact, and continued spread of the disease.

Density dependent diseases are significantly less likely to cause extinction of a population,[2] as the natural course of disease will bring down the density, and thus the propinquity of individuals in the population. In other words, less individuals—as caused by disease—means lower infection rates and a population equilibrium.

Host density-dependent diseases[]

Host density-independent diseases[]

- Chlamydia in koalas

- Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[3]

Contact between individuals within a population as it relates to density in host density-dependent disease[]

This graph shows the direct relationship between disease spread through contact and population density. As the population density increases, so do transmission events between individuals.

This graph shows the direct relationship between disease spread through contact and population density. As the population density increases, so do transmission events between individuals.

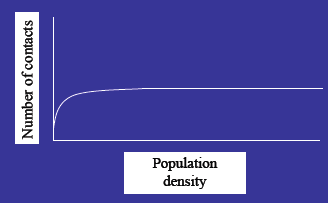

Contact between individuals within a population as it relates to density in sexually transmitted infections[]

There is a rapid initial increase in disease transmission as the population increases from zero, and then the plateau of transmission throughout most of the graph. As sexual contact is required in nearly all sexually reproducing species, transmission is not very host density dependent. It is only in cases of near-extinction where sexually transmitted diseases show any dependence on host density. It is for this reason that sexually transmitted diseases are more likely than density dependent diseases to cause extinction.[4]

Contact between individuals within a population as it relates to density in vector-borne disease[]

This graph shows the relationship between population density and the transmission of vector-borne disease. Initially, the number of contacts between individuals and vectors increases as population density increases. Eventually, however, the advantage of host density diminishes as the density becomes too great for the vector to maintain its natural ecological relationship with the host, and transmission decreases.

References[]

- ^ Begon, M.; Harper, J.L.; Townsend, C.R. (2009). "Glossary: H". In Striano, T.; Reid, V. (eds.). Essentials Of Ecology (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1444305340.

- ^ Holmes, E., Kareiva, P., Sabo, J. (2004). "Efficacy of Simple Viability Models in Ecological Risk Assessment: Does Density Dependence Matter?". Ecology. 85 (2): 328–341. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.452.245. doi:10.1890/03-0035. JSTOR 3450199.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Wobeser, Gary A. (2005). Essentials of Disease in Wild Animals. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-8138-0589-4.

- ^ Cabaret, J.; Hugonnet, L. (1987). "Infection of roe-deer in France by the lung nematode, Dictyocaulus eckerti Skrjabin, 1931 (Trichostrongyloidea): influence of environmental factors and host density". J. Wildl. Dis. 23 (1): 109–12. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-23.1.109. PMID 2950246.

Further reading[]

- (scientific journal articles pertaining to host density and disease)

- Ebert, Dieter (2005). "Ch. 8: Epidemiology". Ecology, Epidemiology, and Evolution of Parasitism in Daphnia. Bethesda MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). ISBN 1-932811-06-0. NBK2036.

- Jaffe, B.; Phillips, R.; Muldoon, A.; Mangel, M. (1992). "Density-Dependent Host-Pathogen Dynamics in Soil Microcosms". Ecology. 73 (2): 495–506. doi:10.2307/1940755. JSTOR 1940755.

- Lentz, Amanda Jean (2007). The Effect of Aphids in Parasitoid-Caterpillar-Plant Interactions (PhD thesis). Blacksburg, VA: University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. etd-07262007-141303.

External links[]

- Disease ecology

- Conservation biology

- Epidemiology

- Ecology

- Habitat