Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Title page of the first three-book edition | |

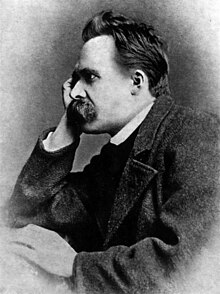

| Author | Friedrich Nietzsche |

|---|---|

| Original title | Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Publisher | Ernst Schmeitzner |

Publication date | 1883–1892 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Preceded by | The Gay Science |

| Followed by | Beyond Good and Evil |

| Text | Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None at Wikisource |

Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None (German: Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen) also translated as Thus Spake Zarathustra, is a work of philosophical fiction written by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche between 1883 and 1885. The protagonist is nominally the historical Zarathustra, but, besides a handful of sentences, Nietzsche is not particularly concerned with any resemblance. Much of the book purports to be what Zarathustra said, and it repeats the refrain, "Thus spoke Zarathustra".

The style of Zarathustra has facilitated variegated and often incompatible ideas about what Zarathustra says. "Zarathustra speaks about stars, animals, trees, tarantulas, dreams, and so forth".[1] Though there is no consensus with what Zarathustra means when he speaks, there is some consensus with what he speaks about. Zarathustra deals with ideas about the Übermensch, the death of God, the will to power, and eternal recurrence.

Zarathustra himself first appeared in Nietzsche's earlier book The Gay Science. Nietzsche has suggested that his Zarathustra is a tragedy and a parody and a polemic and the culmination of the German language. It was his favourite of his own books. He was aware, however, that readers might not understand it. Possibly this is why he subtitled it A Book for All and None. But as with the content whole, the subtitle has baffled many critics, and there is no consensus.

Zarathustra's themes and merits are continually disputed. It has nonetheless been hugely influential in various facets of culture.

Origins[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Nietzsche was born into, and largely remained within, the Bildungsbürgertum, a sort of highly cultivated middleclass.[2] By the time he was a teenager, he had been writing music and poetry.[3][4] His aunt Rosalie gave him a biography of Alexander von Humboldt for his 15th birthday, and reading this inspired a love of learning "for its own sake".[5] The schools he attended and the books he read and his general milieu fostered and inculcated his interests in Bildung, or selfdevelopment – a concept at least tangential to many in Zarathustra – and he worked extremely hard. He became an outstanding philologist almost accidentally, and he renounced his ideas about being an artist. As a philologist he became particularly sensitive to the transmissions and modifications of ideas,[6] which also bears relevance into Zarathustra. Nietzsche's growing distaste toward philology, however, was yoked with his growing taste toward philosophy. As a student, this yoke was his work with Diogenes Laertius. Even with that work he strongly opposed received opinion. With subsequent and properly philosophical work he continued to oppose received opinion.[7] His books leading up to Zarathustra have been described as nihilistic destruction.[7] Such nihilistic destruction combined with his increasing isolation and the rejection of his marriage proposals (to Lou Andreas-Salomé) and devastated him.[7] While he was working on Zarathustra he was walking very much.[7] The imagery of his walks mingled with his physical and emotional and intellectual pains and his prior decades of hard work. What "erupted" was Thus Spoke Zarathustra.[7]

Nietzsche has said that the central idea of Zarathusta is the eternal recurrence. He has also said that this central idea first occurred to him in August 1881: he was near a "pyramidal block of stone" while walking through the woods along the shores of Lake Silvaplana in the Upper Engadine, and he made a small note that read "6,000 feet beyond man and time."[clarification needed][8]

A few weeks after meeting this idea, he paraphrased in a notebook something written by Friedrich von Hellwald about Zarathustra.[9] This paraphrase was developed into the beginning of Thus Spoke Zarathustra.[9]

A year and a half after making that paraphrase, Nietzsche was living in Rapallo.[9] Nietzsche claimed that the entire first part was conceived, and that Zarathustra himself "came over him", while walking. He was regularly walking "the magnificent road to Zoagli" and "the whole Bay of Santa Margherita".[10] He said in a letter that the entire first part "was conceived in the course of strenuous hiking: absolute certainty, as if every sentence were being called out to me".[10]

Nietzsche returned to "the sacred place" in the summer of 1883 and he "found" the second part".[9]

Nietzsche was in Nice the following winter and he "found" the third part.[9]

According to Nietzsche in Ecce Homo it was "scarcely one year for the entire work", and ten days each part.[9] More broadly, however, he said in a letter: "The whole of Zarathustra is an explosion of forces that have been accumulating for decades".[10]

In January 1884 Nietzsche had finished the third part and thought the book finished.[9] But by November he expected a fourth part to be finished by January.[9] He also mentioned a fifth and sixth part leading to Zarathustra's death, "or else he will give me no peace".[10] But after the fourth part was finished he called it "a fourth (and last) part of Zarathustra, a kind of sublime finale, which is not at all meant for the public".[10]

The first three parts were initially published individually and were first published together in a single volume in 1887.[citation needed] The fourth part was written in 1885 and kept private.[9] While Nietzsche retained mental capacity and was involved in the publication of his works, forty-five copies of the fourth part were printed at his own expense and distributed to his closest friends, to whom he expressed "a vehement desire never to have the Fourth Part made public".[9] In 1889, however, Nietzsche became significantly incapacitated. In March 1892 the four parts were published in a single volume.[9]

Synopsis[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (May 2021) |

Themes[]

This section needs expansion with: Each subsection implies that there is consensus. There is no consensus. You can help by . (April 2021) |

Scholars have argued that "the worst possible way to understand Zarathustra is as a teacher of doctrines".[11] Nonetheless Thus Spoke Zarathustra "has contributed most to the public perception of Nietzsche as philosopher – namely, as the teacher of the 'doctrines' of the will to power, the overman and the eternal return".[12]

Will to power[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2021) |

Now hear my word, you who are wisest! Test in earnest whether I have crept into the very heart of Life, and into the very roots of her heart!

Nietzsche, translated by Parkes, On Self-Overcoming

Nietzsche's thinking was significantly influenced by the thinking of Arthur Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer emphasised will, and particularly will to live. Nietzsche emphasised Wille zur Macht, or will to power. Will to power has been one of the more problematic of Nietzsche's ideas.

Nietzsche was not a systematic philosopher and left much of what he wrote open to interpretation. Receptive fascists are said to have misinterpreted the will to power, having overlooked Nietzsche's distinction between Kraft ("force" or "strength") and Macht ("power" or "might").[13]

Scholars have often had recourse to Nietzsche's notebooks, where will to power is described in ways such as "willing-to-become-stronger [Stärker-werden-wollen], willing growth".[14]

Übermensch[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2021) |

You have made your way from worm to human, and much in you is still worm.

Nietzsche, translated by Parkes, Zarathustra's Prologue

It is allegedly "well-known that as a term, Nietzsche’s Übermensch derives from Lucian of Samosata's hyperanthropos".[15] This hyperanthropos, or overhuman, appears in Lucian's Menippean satire Κατάπλους ἢ Τύραννος, usually translated Downward Journey or The Tyrant. This hyperanthropos is "imagined to be superior to others of 'lesser' station in this-worldly life and the same tyrant after his (comically unwilling) transport into the underworld".[15] Nietzsche celebrated Goethe as an actualisation of the Übermensch.[7]

Eternal recurrence[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2021) |

Thus I was talking, and ever more softly: for I was afraid of my own thoughts and the motives behind them.

Nietzsche, translated by Parkes, On the Vision and the Riddle

Interpretations of the eternal recurrence have mostly revolved around cosmological and attitudinal and normative principles.[16]

As a cosmological principle, it has been supposed to mean that time is circular, that all things recur eternally.[17] A weak attempt at proof has been noted in Nietzsche's notebooks, and it is not clear to what extent, if at all, Nietzsche believed in the truth of it.[18] Critics have mostly dealt with the cosmological principle as a puzzle of why Nietzsche might have touted the idea.

As an attitudinal principle it has often been dealt with as a thought experiment, to see how one would react, or as a sort of ultimate expression of life-affirmation, as if one should desire eternal recurrence.[19]

As a normative principle, it has been thought of as a measure or standard, akin to a "moral rule".[20]

Criticism of Religion(s)[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2021) |

Ah, brothers, this God that I created was humans'-work and -madness, just like all Gods!

Nietzsche, translated by Parkes, On Believers in a World Behind

Nietzsche studied extensively and was very familiar with Schopenhauer and Christianity and Buddhism, each of which he considered nihilistic and "enemies to a healthy culture".[21] Thus Spoke Zarathustra can be understood as a "polemic" against these influences.[22]

Though Nietzsche "probably learned Sanskrit while at Leipzig from 1865 to 1868",[23] and "was probably one of the best read and most solidly grounded in Buddhism for his time among Europeans",[24] Nietzsche was writing when Eastern thought was only beginning to be acknowledged in the West, and Eastern thought was easily misconstrued.[25] Nietzsche's interpretations of Buddhism were coloured by his study of Schopenhauer,[26] and it is "clear that Nietzsche, as well as Schopenhauer, entertained inaccurate views of Buddhism".[27] An egregious example has been the idea of śūnyatā as "nothingness" rather than "emptiness".[28] "Perhaps the most serious misreading we find in Nietzsche's account of Buddhism was his inability to recognize that the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness was an initiatory stage leading to a reawakening".[29] Nietzsche dismissed Schopenhauer and Christianity and Buddhism as pessimistic and nihilistic, but, according to Benjamin A. Elman, "[w]hen understood on its own terms, Buddhism cannot be dismissed as pessimistic or nihilistic".[30] Moreover, answers which Nietzsche assembled to the questions he was asking, not only generally but also in Zarathustra, put him "very close to some basic doctrines found in Buddhism".[31] An example is when Zarathustra says that "the soul is only a word for something about the body".[32]

Nihilism[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (July 2021) |

'Verily,' he said to his disciples, 'just a little while and this long twilight will be upon us'.

Nietzsche, translated by Parkes, The Soothsayer

It has been often repeated in some way that Nietzsche takes with one hand what he gives with the other. Accordingly, interpreting what he wrote has been notoriously slippery. One of the most vexed points in discussions of Nietzsche has been whether or not he was a nihilist.[33] Though arguments have been made for either side, what is clear is that Nietzsche was at least interested in nihilism.

As far as nihilism touched other people, at least, metaphysical understandings of the world were progressively undermined until people could contend that "God is dead".[7] Without God, humanity was greatly devalued.[7] Without metaphysical or supernatural lenses, humans could be seen as animals with primitive drives which were or could be sublimated.[7] According to Hollingdale, this led to Nietzsche's ideas about the will to power.[7] Likewise, "Sublimated will to power was now the Ariadne's thread tracing the way out of the labyrinth of nihilism".[7]

Style[]

This section needs expansion with: Nietzsche's general style and epistemology at least. You can help by . (May 2021) |

Of all that is written, I love only that which one writes with one's own blood."[34]

Thus Spoke Zarathustra, The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Volume VI, 1899, C. G. Naumann, Leipzig.

My style is a dance.

Nietzsche, letter to Erwin Rohde.[9]

The nature of the text is musical and operatic.[9] While working on it Nietzsche wrote "of his aim 'to become Wagner's heir'".[9] Nietzsche thought of it as akin to a symphony or opera.[9] "No lesser a symphonist than Gustav Mahler corroborates: 'His Zarathustra was born completely from the spirit of music, and is even "symphonically constructed"'".[9] Nietzsche

later draws special attention to "the tempo of Zarathustra's speeches" and their "delicate slowness" – "from an infinite fullness of light and depth of happiness drop falls after drop, word after word" – as well as the necessity of "hearing properly the tone that issues from his mouth, this halcyon tone".[9]

The length of paragraphs and the punctuation and the repetitions all enhance the musicality.[9]

The title is Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Much of the book is what Zarathustra said. What Zarathustra says

is throughout so highly parabolic, metaphorical, and aphoristic. Rather than state various claims about virtues and the present age and religion and aspirations, Zarathustra speaks about stars, animals, trees, tarantulas, dreams, and so forth. Explanations and claims are almost always analogical and figurative.[35]

Nietzsche would often appropriate masks and models to develop himself and his thoughts and ideas, and to find voices and names through which to communicate.[36] While writing Zarathustra, Nietzsche was particularly influenced by "the language of Luther and the poetic form of the Bible".[9] But Zarathustra also frequently alludes to or appropriates from Hölderlin's Hyperion and Goethe's Faust and Emerson's Essays, among other things. It is generally agreed that the sorcerer is based on Wagner and the soothsayer is based on Schopenhauer.

The original text contains a great deal of word-play. For instance, words beginning with über ('over, above') and unter ('down, below') are often paired to emphasise the contrast, which is not always possible to bring out in translation, except by coinages. An example is untergang (lit. 'down-going'), which is used in German to mean 'setting' (as in, of the sun), but also 'sinking', 'demise', 'downfall', or 'doom'. Nietzsche pairs this word with its opposite übergang ('over-going'), used to mean 'transition'. Another example is übermensch ('overman' or 'superman').

Reception and influence[]

Critical[]

Nietzsche wrote in a letter of February 1884:

With Zarathustra I believe I have brought the German language to its culmination. After Luther and Goethe there was still a third step to be made.[9]

To this, Parkes has said: "Many scholars believe that Nietzsche managed to make that step".[9] But critical opinion varies extremely. The book is "a masterpiece of literature as well as philosophy"[9] and "in large part a failure".[35]

Nietzsche[]

Nietzsche has said that "among my writings my Zarathustra stands to my mind by itself."[37] Emphasizing its centrality and its status as his magnum opus, Nietzsche has stated that:

With [Thus Spoke Zarathustra] I have given mankind the greatest present that has ever been made to it so far. This book, with a voice bridging centuries, is not only the highest book there is, the book that is truly characterized by the air of the heights—the whole fact of man lies beneath it at a tremendous distance—it is also the deepest, born out of the innermost wealth of truth, an inexhaustible well to which no pail descends without coming up again filled with gold and goodness.

— Ecce Homo, "Preface" §4, translated by W. Kaufmann

Not Nietzsche[]

This section needs expansion with: things more comprehensive and relevant. You can help by . (May 2021) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

The style of the book, along with its ambiguity and paradoxical nature, has helped its eventual enthusiastic reception by the reading public, but has frustrated academic attempts at analysis (as Nietzsche may have intended). Thus Spoke Zarathustra remained unpopular as a topic for scholars (especially those in the Anglo-American analytic tradition) until the latter half of the 20th century brought widespread interest in Nietzsche and his unconventional style.[38]

The critic Harold Bloom criticized Thus Spoke Zarathustra in The Western Canon (1994), calling the book "a gorgeous disaster" and "unreadable."[39] Other commentators have suggested that Nietzsche's style is intentionally ironic for much of the book.

Literary[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (July 2021) |

Memorial[]

Text from Thus Spoke Zarathustra constitutes the Nietzsche memorial stone that was erected at Lake Sils in 1900, the year Nietzsche died.

Musical[]

19th century[]

- "Zarathustra's Roundelay" was set as part of Gustav Mahler's Third Symphony, originally under the title What Man Tells Me, or alternatively What the Night Tells Me (Of Man).

- Richard Strauss composed the tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra, which he designated "freely based on Friedrich Nietzsche."[40]

20th century[]

- Frederick Delius based his major choral-orchestral work A Mass of Life (1904–5) on texts from Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The work ends with a setting of "Zarathustra's Roundelay" which Delius had composed earlier, in 1898, as a separate work.

- Carl Orff composed a three-movement setting of part of Nietzsche's text as a teenager, but this has remained unpublished.

- The short score of the third symphony by Arnold Bax originally began with a quotation from Thus Spoke Zarathustra: "My wisdom became pregnant on lonely mountains; upon barren stones she brought forth her young."

- Another setting of the roundelay is one of the songs of Lukas Foss's Time Cycle for soprano and orchestra.

- Italian progressive rock band Museo Rosenbach released the album Zarathustra, with lyrics referring to the book.

21st century[]

- The[which?] English translation of part 2 chapter 7, Tarantulas, has been narrated by Jordan Peterson[41] and musically toned by artist Akira the Don.[42]

Philosophical[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (July 2021) |

Political[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2021) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

In 1893, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche returned to Germany from administrating a failed colony in Paraguay and took charge of Nietzsche's manuscripts. Nietzsche was by this point incapacitated. Förster-Nietzsche edited the manuscripts and invented false biographical information and fostered affiliations with the Nazis. The Nazis issued special editions of Zarathustra to soldiers.

Visual[]

- Between 1995 and 1997 Lena Hades created a series of oil paintings, or "visual metaphors", based on and named after the book.

Video games[]

- Also Sprach Zarathustra is referenced in the Xenosaga video-game series, the plot of which covers similar topics that Nietzsche covers in his writings. The book is most explicitly used by the series in its third episode, Xenosaga Episode III: Also Sprach Zarathustra (2006).

English translations[]

The first English translation of Zarathustra was published in 1896 by Alexander Tille.

Common (1909)[]

Thomas Common published a translation in 1909 which was based on Alexander Tille's earlier attempt.[43] Common wrote in the style of Shakespeare or the King James Version of the Bible.[clarification needed] Common's poetic interpretation of the text, which renders the title Thus Spake Zarathustra, received wide acclaim for its lambent portrayal.[citation needed] Common reasoned that because the original German was written in a pseudo-Luther-Biblical style, a pseudo-King-James-Biblical style would be fitting in the English translation.

Kaufmann's introduction to his own translation included a blistering critique of Common's version; he notes that in one instance, Common has taken the German "most evil" and rendered it "baddest", a particularly unfortunate error not merely for his having coined the term "baddest", but also because Nietzsche dedicated a third of The Genealogy of Morals to the difference between "bad" and "evil."[43] This and other errors led Kaufmann to wonder whether Common "had little German and less English."[43]

The German text available to Common was considerably flawed.[44]

From Zarathustra's Prologue:

The Superman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: The Superman shall be the meaning of the earth!

I conjure you, my brethren, remain true to the earth, and believe not those who speak unto you of superearthly hopes! Poisoners are they, whether they know it or not.

Kaufmann (1954) and Hollingdale (1961)[]

The Common translation remained widely accepted until more critical translations, titled Thus Spoke Zarathustra, were published by Walter Kaufmann in 1954,[45] and R.J. Hollingdale in 1961,[46] which are considered to convey the German text more accurately than the Common version. The translations of Kaufmann and Hollingdale render the text in a far more familiar, less archaic, style of language, than that of Common. However, "deficiencies" have been noted.[47]

The German text from which Hollingdale and Kaufmann worked was untrue to Nietzsche's own work in some ways.[44] Martin criticizes Kaufmann for changing punctuation, altering literal and philosophical meanings, and dampening some of Nietzsche's more controversial metaphors.[44] Kaufmann's version, which has become the most widely available, features a translator's note suggesting that Nietzsche's text would have benefited from an editor; Martin suggests that Kaufmann "took it upon himself to become [Nietzsche's] editor."[44]

Kaufmann, from Zarathustra's Prologue:

The overman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: the overman shall be the meaning of the earth! I beseech you, my brothers, remain faithful to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of otherworldly hopes! Poison-mixers are they, whether they know it or not.

Hollingdale, from Zarathustra's Prologue:

The Superman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: the Superman shall be the meaning of the earth!

I entreat you, my brothers, remain true to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of superterrestrial hopes! They are poisoners, whether they know it or not.

Wayne (2003)[]

Thomas Wayne, an English Professor at Edison State College in Fort Myers, Florida, published a translation in 2003. The introduction by Roger W. Phillips, Ph.D., says "Wayne's close reading of the original text has exposed the deficiencies of earlier translations, preeminent among them that of the highly esteemed Walter Kaufmann", and gives several reasons.

Martin (2005)[]

This section needs expansion with: Something about this translation and not others. You can help by . (May 2021) |

Parkes (2005) and Del Caro (2006)[]

This section needs expansion with: These two editions are favoured by Anglophone Nietzsche scholars. You can help by . (May 2021) |

Graham Parkes describes his own 2005 translation as trying "above all to convey the musicality of the text."[48] In 2006, Cambridge University Press published a translation by Adrian Del Caro, edited by Robert Pippin.

Parkes, from Zarathustra's Prologue:

The Overhuman is the sense of the earth. May your will say: Let the Overhuman be the sense of the earth!

I beseech you, my brothers, stay true to the earth and do not believe those who talk of over-earthly hopes! They are poison-mixers, whether they know it or not.

Del Caro, from Zarathustra's Prologue:

The overman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: the overman shall be the meaning of the earth!

I beseech you, my brothers, remain faithful to the earth and do not believe those who speak to you of extraterrestrial hopes! They are mixers of poisons whether they know it or not.

Further reading[]

Selected editions[]

English[]

- Thus Spake Zarathustra, translated by Alexander Tille. New York: Macmillan. 1896.

- Thus Spake Zarathustra, trans. Thomas Common. Edinburgh: T. N. Foulis. 1909.

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Random House. 1954.

- Reprints: In The Portable Nietzsche, New York: Viking Press. 1954; Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 1976

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. R. J. Hollingdale. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 1961.

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. Graham Parkes. Oxford: Oxford World's Classics. 2005.

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. Clancy Martin. Barnes & Noble Books. 2005.

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. Adrian del Caro and edited by Robert Pippin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006.

German[]

- Also sprach Zarathustra, edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag (study edition of the standard German Nietzsche edition).

- Also sprach Zarathustra (bilingual ed.) (in German and Russian), with 20 oil paintings by Lena Hades. Moscow: Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences. 2004. ISBN 5-9540-0019-0.

Commentaries and introductions[]

English[]

- Nietzsche's 'Thus Spoke Zarathustra': Before Sunrise (essay collection), edited by James Luchte. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. 2008. ISBN 1-84706-221-0.

- Higgins, Kathleen. [1987]. 2010. Nietzsche's Zarathustra (rev. ed.). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- OSHO. 1987. "Zarathustra: A God That Can Dance." Pune, Indiana: OSHO Commune International.

- Lampert, Laurence. 1989. Nietzsche's Teaching: An Interpretation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rosen, Stanley. 1995. The Mask of Enlightenment: Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2004.

- Seung, T. K. 2005. Nietzsche's Epic of the Soul: Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

German[]

- Naumann, Gustav. 1899–1901. Zarathustra-Commentar (in German), 4 vols. Leipzig: Haessel.

- Zittel, Claus. 2011. Das ästhetische Kalkül von Friedrich Nietzsches 'Also sprach Zarathustra'. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. ISBN 978-3-8260-4649-0.

- Schmidt, Rüdiger. "Introduction" (in German). In Nietzsche für Anfänger: Also sprach Zarathustra – Eine Lese-Einführung.

See also[]

- Faith in the Earth

- Gathas (Hymns of Zoroaster)

- Influence and reception of Friedrich Nietzsche

- Nietzsche and Buddhism

- Nietzsche on the Manusmriti (Ancient text, otherwise known as Mānava-Dharmaśāstra or Laws of Manu).

- Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche

References[]

Notes[]

Citations[]

- ^ Pippin, Int. in TSZ, Cambridge

- ^ Blue, D. (2016), "Chapter 2: Half an orphan" in The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Blue, D. (2016), "Chapter 3: The Discovery of Writing" in The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Blue, D. (2016), "Chapter 4: The Discovery of Self" in The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Blue, D. (2016), "Chapter 5: Soul-building: the theory" in The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Blue, D. (2016), "Chapter 13: 'Become what you are'" in The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Hollingdale, "Introduction" in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Penguin

- ^ Gutmann, James. 1954. "The 'Tremendous Moment' of Nietzsche's Vision." The Journal of Philosophy 51(25):837–42. doi:10.2307/2020597. JSTOR 2020597.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Parkes, "Introduction" in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Oxford

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Nietzsche, cited in Parkes, "Introduction" in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Oxford

- ^ Pippin, Robert B. (2019), "Figurative Philosophy in Beyond Good and Evil", in The New Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche, pp. 195-221

- ^ Johnson, Dirk R. (2019), "Zarathustra: Nietzsche's Rendezvous with Eternity", in The New Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche, pp. 173-194

- ^ Golomb, Jacob (2002). Nietzsche, Godfather of Fascism? On the Uses and Abuses of a Philosophy.

- ^ Dunkle, I.D. (2020). On the Normativity of Nietzsche's Will to Power. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies 51(2), 188-211. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/773967.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Babich, Babette, "Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and Parodic Style: On Lucian’s Hyperanthropos and Nietzsche’s Übermensch" (2013). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 56. https://research.library.fordham.edu/phil_babich/56

- ^ Sinhababu, N., & Teng, K.U. (2019). Loving the Eternal Recurrence. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies 50(1), 106-124. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/721006.

- ^ Sinhababu, N., & Teng, K.U. (2019). Loving the Eternal Recurrence. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies 50(1), 106-124. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/721006.

- ^ Sinhababu, N., & Teng, K.U. (2019). Loving the Eternal Recurrence. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies 50(1), 106-124. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/721006.

- ^ Sinhababu, N., & Teng, K.U. (2019). Loving the Eternal Recurrence. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies 50(1), 106-124. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/721006.

- ^ Sinhababu, N., & Teng, K.U. (2019). Loving the Eternal Recurrence. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies 50(1), 106-124. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/721006.

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Elman, B. A. (1983) Nietzsche and Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709223

- ^ Parkes trans.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pippin, "Introduction" in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Cambridge

- ^ Kofman, Sarah And Yet It Quakes! (Nietzsche and Voltaire), https://doi.org/10.3366/para.2021.0358 accessed 9 Aug 2021

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich. [publ. 1908] 1967. "Preface." In Ecce Homo, translated and edited by W. Kaufmann. New York: Vintage. § 4.

- ^ Behler, Ernst. 1996. "Nietzsche in the Twentieth Century." Pp. 281–319 in The Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche, edited by Magnus and Higgins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. New York: Riverhead Books. pp. 196, 422. ISBN 1-57322-514-2.

- ^ Bernard Jacobson. "Richard Strauss, Also Sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 (1896)". American Symphony Orchestra: Dialogues and Extensions. Archived from the original on 2007-10-15. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ 1791 (user). 9 October 2018. "TARANTULAS | Friedrich Nietzsche." YouTube. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ "Akira The Don – Tarantulas Lyrics." Genius. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Nietzsche, Friedrich. Trans. Kaufmann, Walter. The Portable Nietzsche. 1976, pp. 108–09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nietzsche, Friedrich. Trans. Martin, Clancy. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. 2005, p. xxxiii.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1954). The Portable Nietzsche. trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Penguin.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich. [1883–1885] 1961. Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by R. J. Hollingdale. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- ^ q.v. #Wayne (2003)

- ^ Parkes, Graham. 2005. "Prologue." In Thus spoke Zarathustra. p. xxxv.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thus Spoke Zarathustra |

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra at Standard Ebooks

- Also sprach Zarathustra at Nietzsche Source

- Project Gutenberg's etext of Also sprach Zarathustra (the German original)

- Project Gutenberg's etext of Thus Spake Zarathustra, translated by Thomas Common

Thus Spake Zarathustra public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Thus Spake Zarathustra public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra

- 1883 German novels

- Books critical of Christianity

- Anti-Christian sentiment in Europe

- Books by Friedrich Nietzsche

- Ethics books

- German philosophical novels

- Philosophy of religion literature