Tinder (app)

This article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| |

| Founded | 2012 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | West Hollywood, Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Area served | Global |

| Owner | Match Group |

| Founder(s) |

|

| CEO | Renate Nyborg[1] |

| Industry | Software |

| Employees | 750[2] |

| URL | www |

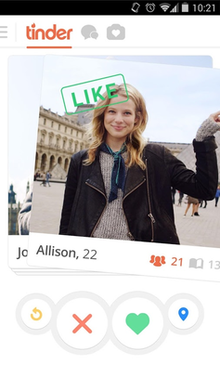

Example of swiping within Tinder | |

| Developer(s) | Tinder, Inc. |

|---|---|

| Initial release | September 12, 2012 |

| Operating system | iOS, Android, Web |

| Available in | 56 [3] languages |

List of languages

| |

| Website | tinder |

Tinder is an online dating and geosocial networking application. Users anonymously "swipe right" to like or "swipe left" to dislike other users' profiles, which include their photo, a short bio, and a list of their interests. Tinder uses a "double opt-in" system where both users must have "swiped right" to match before they can exchange messages.[4][5][6][7]

Sean Rad founded Tinder in 2012 at a hackathon held at the startup incubator Hatch Labs in West Hollywood.[8][9][10] By 2014, Tinder was registering about one billion daily "swipes" and reported that users logged into the app on average 11 times a day.[11] In 2015, Tinder was the fifth highest-grossing mobile app,[12] and in 2019 it surpassed Netflix in annual spending.[13] In 2020, Tinder had 6.2 million subscribers and 75 million monthly active users.[14] As of 2021, Tinder has recorded more than 65 billion matches worldwide.[15]

History[]

The original prototype for Tinder, called 'MatchBox' was built during a hackathon in February 2012 by Sean Rad and engineer Joe Munoz. The hackathon was hosted by Hatch Labs, a NY-based startup incubator with a West Hollywood outpost. Realizing the name MatchBox was too similar to Match.com, Rad, his co-founders, and early employees renamed the company to Tinder. The company's flame-themed logo remained consistent throughout the rebranding.[16]

2012: Prototype and launch[]

In January 2012, Rad was hired as General Manager of Cardify, a credit card loyalty app launched by Hatch Labs. During a hackathon in his first month, he presented the idea for a dating app called Matchbox. Rad and engineer Joe Munoz built the prototype for MatchBox and presented the "double opt-in" dating app on February 16, 2012.[17][16]

In March, co-founder Jonathan Badeen (front-end operator and later Tinder's CSO), and Chris Gulczynski (designer and later Tinder's CCO) joined Cardify.[18][19][20][21]

In May, while Cardify was going through Apple's App Store approval process, the team focused on MatchBox. During the same period, Alexa Mateen (Justin's sister) and her friend, Whitney Wolfe Herd, were hired as Cardify sales reps.[16]

In August 2012, Cardify was abandoned, Matchbox was renamed Tinder, and co-founder Justin Mateen[22] (marketer and later Tinder's CMO) joined the company.[16]

In September 2012, Tinder soft-launched in the App Store. It was then launched at several college campuses and started to quickly expand.[23]

2013: Swipe feature developed[]

In May 2013, Tinder ranked in the top 25 social networking sites according to app data. Tinder's selection function, which was initially click-based, evolved into the company's swipe feature. The feature was established when Rad and Badeen, interested in gamification - modeled the feature off a deck of cards. Badeen then streamlined the action following trial on a bathroom mirror.[24] Tinder has been credited, with popularizing the swipe feature many other companies now use.[25][26][27][28][29][30][31]

2014–2016: Growth[]

By October 2014, Tinder users completed over one billion swipes per day, producing about twelve million matches per day. By this time, Tinder's average user generally spent about 90 minutes a day on the app.[11]

Founder Sean Rad served as Tinder's CEO until March 2015, when he was replaced by former eBay and Microsoft executive Chris Payne. Rad returned as CEO in August 2015.[32]

In 2015 Tinder released its "Rewind" function, its "Super Like" function, and retired its Tinder "Moments" and "Last Active" feature.[33][34][35][36] In January 2015 Tinder acquired Chill, the developers of Tappy, a mobile messenger that uses "images and ephemerality".[37]

In 2016, Tinder was the most popular dating app in the United States, holding 25.6% market share of monthly users.[38] On the company's third quarter earnings call, Match Group’s CEO Greg Blatt described the popular dating app Tinder as a "rocket" and the "future of this business."[39]

In September 2016, the company also initiated testing of its "Boost" functionality in Australia.[40] The feature went live for all users in October of that year.[41][42]

In October 2016, Tinder announced the opening of its first office in Silicon Valley in the hope of more effectively recruiting technical employees.[43]

In November 2016, Tinder introduced more options for gender selection.[44]

In December 2016, Greg Blatt, CEO and chairman of Tinder's parent company, Match Group, took over as interim CEO of Tinder.[45] Sean Rad stepped down as CEO of Tinder, becoming Chairman of the company.

2017: Match merger with Tinder[]

Tinder had annual revenue of $403 million and accounted for 31% of Match Group's 2017 annual revenue of $1.28 billion.[46] In the same year, Tinder surpassed Netflix as the highest grossing app on the app store.[47] Match Group's market cap as of December 28, 2017 was $10.03 billion.[48]

In 2017, Tinder remained Match Group's strongest earner within their portfolio.[49]

In March 2017, Tinder launched Tinder Online, a web-optimized version of the dating.[50] Initially, it was only available in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia, Italy, Mexico, Philippines and Sweden and did not include special features such as "Super Likes" or "Tinder Boost."[51] Tinder Online launched globally in September 2017.[52] During the launch of the official web version, Tinder took legal action to shut down third-party apps providing a web extension to use the Tinder app from a desktop computer.[53]

In July 2017, Match Group merged with Tinder for approximately $3 billion.[54]

In August 2017, Tinder Gold, a members-only service of exclusive features launched.[55] Tinder Gold became an instant hit, boosting Match Group's total revenue by 19% compared to 2016.[56] This boost in revenue and profits came as Tinder's paid member count rose by a record 476,000 to more than 2.5 million, driven by product changes and technology improvements.[57] The popularity of Tinder Gold led to a surge in Match Group shares and record high share prices. Greg Blatt, Match Group's then-CEO, called Tinder's performance "fantastic," and stated that the company was driving most of Match Group's growth in late 2017.[56]

Blatt resigned from Match Group and Tinder in 2017 following allegations of sexual harassment.[58] He was replaced by Elie Seidman.

2018 - 2019[]

In 2018, Tinder had annual revenue of $805 million and accounted for 48% of Match Group's 2018 annual revenue of $1.67 billion. Match Group's market cap as of December 30, 2018 was $15.33 billion.[48]

On August 6, 2018, Tinder had over 3.7 million paid subscribers, up 81 percent over the same quarter in 2017.[59] On August 21, 2018, Tinder launched Tinder University, a feature that allows college students to connect with other students on their campus and at nearby schools.[60]

In 2019, Tinder had annual revenue of $1.152 billion and accounted for 58% of Match Group's total 2019 annual revenue of $2.0 billion. Match Group's market cap as of December 30, 2019 was $21.09 billion.[48]

On May 10, it was reported that Tinder was planning for a lighter version app called Tinder Lite aimed at growing markets where data usage, bandwidth and storage space are a concern.[61]

On August 6, Tinder had 5.2 million paying subscribers at the end of 2019's second quarter, up 1.5 million from the year-ago quarter and up 503,000 from the first quarter of 2019.[62] Tinder became the highest grossing non-gaming app, beating Netflix[63]. Tinder's subscriber growth led Match Group's shares to the best single-day gain in their history on August 7,[64] adding more than $5 billion to the company's market capitalization.[65]

On September 12, Tinder relaunched Swipe Night, an interactive series where users make decisions following a storyline. Swipe Night had previously been launched in October 2019. It was slated to be launched internationally in March 2020, but it was postponed until September due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Swipe Night's international launch included multiple countries and languages.[66] The three major decisions made in each episode of the interactive series displays on the user's profile and can be used for matching potential.

2020[]

In 2020, Tinder had annual revenue of $1.355 billion and accounted for 58% of Match Group's 2020 revenue of $2.34 billion. Match Group's market cap as of December 23, 2020 was $40.45 billion.[48]

In January 2020, the Tinder administration enabled a panic button and anti-catfishing technology to improve the safety of US users. In the future, these features should become globally available. If something goes wrong on a date, a user can hit a panic button, transmit accurate location data, and call emergency services. To use this feature, users must download and install the Noonlight app.[67] Also, before going to a meeting, users are required to take selfies to prove their photos in Tinder profiles match their real identities.[68]

In response to the global COVID-19 pandemic, in March 2020, Tinder temporarily made its Passport feature available for free to all of its users worldwide. Previously this feature had been only accessible to users who had purchased a subscription.[69]

In August, Tinder revealed plans for their Platinum subscription plan, which gives additional value beyond Tinder's current subscription plan Gold.[70] The same month, Jim Lanzone took over as CEO.

On September 1, Tinder was banned in Pakistan in a crackdown on what the Pakistani government deemed "immoral content".[71][72][73][74]

On November 4, Tinder reported that it did better than expected for the third quarter's earnings, the app saw a growth of revenue and an increase in subscribers during the third quarter, even though it was in the middle of the pandemic. The app was able to grow its user base by 15% since the third quarter of 2019 and received a 16% boost to subscribers. Tinder has 6.6 million subscribers globally, growing since June, when the company reported 6.2 million.[75]

2021 - Present[]

Match Group's market cap as of October 14, 2021 was $44.59 billion.[48]

In February 2021, Tinder announced it would be launching a range of mobile accessories under the brand name Tinder Made.[76] The app reported that month an all-time high in users ready to "go on a date" as opposed to virtual and online chats during the height of the pandemic in the United States. It gave away pairs of testing kits to some matches to encourage responsible behavior as users begin to meet in person again.[77]

In March 2021, Tinder announced a service that would let users run background checks on potential matches after an investment in Garbo, a company that "collects public records and reports of violence or abuse, including arrests, convictions, restraining orders, harassment, and other violent crimes".[78] Garbo does not publicize drug possession charges or traffic violations, citing disproportionate incarceration. This service comes with a fee that has not yet been disclosed to users.[49]

In August 2021, Tinder announced to introduce an ID verification service available for users around the world, in order to tackle catfishing or duping someone into a relationship by using false pictures and information.[79]

In September 2021, Jim Lanzone announced that he was stepping down from his position of Chief Executive to pursue a new role with Yahoo.[80] This prompted Tinder to name Renate Nyborg as CEO. She is the company's first female CEO.[81]

In December 2021, Nyborg announced that the company is working on creating a metaverse called Tinderverse, a shared virtual reality. The company is also testing an in-app currency users can earn as a reward for good behavior, allowing them to pay for the platform's premium services.[82]

Operation[]

After building a profile with a Facebook login or cell phone number, users can swipe yes (right) or no (left) to determine if they have a potential romantic match. Chatting on Tinder is only available between two users that have swiped right on one another's photos.[83][84] The selections a user makes are not known to other users unless two individuals swipe right on each other's profiles. However, once the user has matches on the app, they are able to send personal photos, called "Tinder Moments", to all matches at once, allowing each match to like or not like the photos. The site also has verified profiles for public figures, so that celebrities and other public figures can verify they are who they are when using the app.[85][86]

The app is currently used in about 196 countries and is available in 56 languages.

Financials[]

Since merging with Tinder in July 2017, Match Group's market capitalization has grown from $8.34 billion to $44.59 billion as of October 14, 2021.[48] In August 2021, Morgan Stanley valued Tinder's worth at $42 billion.[87][88] The valuation is based on a multiple of 40x EBITDA, similar to its counterpart Bumble.[87]

In March 2014, media and internet conglomerate IAC increased its majority stake in Tinder, a move that which is believed to have valued Tinder at several billion dollars.[26] In July 2015, Tinder was valued at $1.35 billion by Bank of America Merrill Lynch based upon an estimate of $27 per user on an estimated user base of 50 million with an additional bullish estimate of $3 billion by taking the average of the IPOs of similar companies. Analysts also estimated that Tinder had about half a million paid users within its userbase that consisted mostly of free users.[89] The monetization of the site has come through leaving the basic app free and then adding different in-app purchase options for additional functions.[27]

Paid subscriptions[]

In March 2015, Tinder released its paid service, Tinder Plus, a feature allowing unlimited matches, whereas the free Tinder app limits the number of right swipes in a 12-hour period. It has met with controversy over limiting the number of "likes" a free user can give in a certain amount of time, as well as charging prices for different age groups.[90] The price of a Tinder Plus subscription was £14.99/US$19.99 per month for users over 28, while the service for a user 28 and under was £3.99/US$9.99 per month.[91][92]

In 2016, Tinder independently increased paying members by nearly one million, while Match Group's 44 other brands added just 1.4 million.[39]

In June 2017, Tinder launched Tinder Gold, a members-only service that offers users Tinder's most exclusive features: Passport, Rewind, Unlimited Likes, Likes You, five Super Likes per day, one Boost per month, and more profile controls. The price of a monthly membership started at $14.99 per month for users under 30 and $29.99 per month for users over 30.[93]

As of December 2020, Tinder had 6.6 million paid users.[94] According to a Match Group SEC filing, the growth in international and North America average subscribers was primarily driven by Tinder.[95]

Users[]

Tinder is used widely throughout the world and is available in over 190 countries and 56 languages.[96] As of September 2021, an estimated 75 million people used the app every month. In late 2014, Tinder users averaged 12 million matches per day. However, to get to those 12 million matches, users collectively made around 1 billion swipes per day. Tinder now limits users' number of available swipes per 12 hours based on an algorithm to make sure users were actually looking at profiles and not just spamming the app to rack up random matches.[97] The minimum age to sign up and use Tinder was 18. As of June 2016, Tinder is no longer usable by anyone under 18. If minors were found being under 18, they were banned from using Tinder until they were 18.[98][99] As of April 2015, Tinder users swiped through 1.6 billion Tinder profiles and made more than 26 million matches per day.[100] More than 558 billion matches have been made since Tinder launched in 2012.[101]

Features[]

- Swipe is central to Tinder's design. The app's algorithm presents profile to users, who then swipe right to "like" potential matches and swipe left to continue their search.[102]

- Messaging is also a heavily utilized feature. Once a user matches with another user, they are able to exchange text messages on the app.[103]

- Face to Face is Tinder's video chat feature that allows users who have matched to see each other virtually. It was implemented in July 2020.[104]

- Instagram integration lets users view other users' Instagram profiles.[105]

- Common Connections allows users to see whether they share a mutual Facebook friend with a match (a first-degree connection on Tinder) or when a user and their match have two separate friends who happen to be friends with each other (considered second-degree on Tinder).[105][106]

- Tinder Gold, introduced worldwide in August 2017, is a premium subscription feature that allows users to see those who have already liked them before swiping.[107]

- Panic button was introduced in the US in January 2020. The feature provides emergency assistance, location tracking, and photo verification.[108]

- Traveler alert was introduced in 2019 to alert Tinder users of the LGBTQ+ community of possible penalization they are subject to when they travel to a country or geographical location that does not allow such interaction. This feature automatically hides users' profiles in countries that prohibit same-sex relationships, then allowing the user to decide if they prefer to stay hidden or not.[109]

- Plus One was announced by Tinder in October 2021 as a way for users to connect with each other on the Explore page to arrange a date for weddings. Users are able to signify if they are looking for, or are willing to be a wedding date.[110]

Advertising[]

An ad campaign launched by "The Barn" internship program of Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BBH) used Tinder profiles to promote their NYC Puppy Rescue Project.[111] Using Facebook pet profiles, BBH was able to add them to the Tinder network. The campaign received media coverage from Slate, Inc., The Huffington Post, and others.[112] In April 2015, Tinder revealed their first sponsored ad promoting Budweiser's next #Whatever, USA campaign.[113]

On December 11, Tinder announced their partnership with popular artist Megan Thee Stallion for the Put Yourself Out There Challenge, giving $10,000 to users who made unique profiles.[114]

Lawsuits[]

On June 30, 2014, former vice president of marketing Whitney Wolfe filed a sexual harassment and sex discrimination suit in Los Angeles County Superior Court against IAC-owned Match Group, the parent company of Tinder. The lawsuit alleged that Rad and Mateen had engaged in discrimination, sexual harassment, and retaliation against her, while Tinder's corporate supervisor, IAC's Sam Yagan, did nothing.[115] IAC suspended CMO Mateen from his position pending an ongoing investigation, and stated that it "acknowledges that Mateen sent private messages containing 'inappropriate content, but it believes Mateen, Rad and the company are innocent of the allegations".[116] The suit was settled with no admission of wrongdoing, and Wolfe reportedly received over $1 million from the settlement.[19][117]

In March, 2018 Match Group sued Bumble, arguing that the dating app was guilty of patent infringement and of stealing trade secrets from Tinder.[118] In June 2020, an undisclosed settlement was reached between Match Group and Bumble to settle all litigations.[119]

In December 2018, The Verge reported that Tinder had dismissed Rosette Pambakian, the company's vice president of marketing and communication. Pambakian alleged former Match Group and IAC CEO Greg Blatt, sexually assaulted her in a hotel room following a company party in December 2016. She further accuses the company of firing her when she reported the incident.[120][121]

In September 2019, the US Federal Trade Commission sued Tinder's parent company, The Match Group, for knowingly using and/or creating fake users to bait men into paying for subscriptions. The claim includes romance scams, phishing scams, fraudulent advertising, and extortion scams. The suit claims that The Match Group indirectly profited from these scams at consumers' expense.[122]

In August 2018, co-founders Sean Rad and Justin Mateen and eight other former and current executives of Tinder filed a lawsuit against Match Group and IAC, alleging that they manipulated the 2017 valuation of the company to deny them of billions of dollars they were owed.[123] The suit charges that executives of Match Group and IAC deliberately manipulated the data given to the banks, overestimating expenses and underestimating potential revenue growth, in order to keep the 2017 valuation artificially low. Tinder's 2017 valuation was set at $3 billion, unchanged from a valuation that had been done two years earlier, despite rapid growth in revenue and subscribers.[123] The plaintiffs sought upwards of $2 billion in damages. The trial is scheduled to begin on November 8, 2021.[124]

Criticism[]

Privacy concerns[]

There are cybersecurity, data privacy, and public health concerns about Tinder. Public health officials in Rhode Island and Utah have claimed that Tinder and similar apps are responsible for an uptick of some STDs.[125] In February 2014, security researchers in New York found a flaw which made it possible to find users' precise locations for between 40 and 165 days. Tinder's spokesperson, Rosette Pambakian, said the issue was resolved within 48 hours. Tinder CEO Sean Rad said in a statement that shortly after being contacted, Tinder implemented specific measures to enhance location security and further obscure location data.[126]

In August 2016, two engineers found another flaw that showed all users' matches' exact location. The location was updated every time a user logged into the app and it worked even for blocked matches. The issue was detected in March 2016, but it was not fixed until August 2016.[127] In July 2017, a study published in Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing found that Tinder users are excessively willing to disclose their personally identifiable information.[128] In September 2017, The Guardian published an article by a journalist who requested all data that the Tinder app had recorded about her from the company and found that Tinder stores all user messages, user locations and times, the characteristics of other users who interest a particular user, the characteristics of particular users of interest to other users, and the length of time users spend looking at particular pictures, which for the journalist amounted to 800 pages of detail.[129]

Safety[]

In 2021, Tinder partnered with and invested in Garbo, a non-profit background check company. The partnership was intended to add a feature enabling users to run background checks on their matches. Critics believed the integration of background check software discriminates against one-third of the adult working population in the US who have criminal records. Another issue that critics raised was the unreliability of background checks since they disproportionately impact people from Black and other ethnic minorities. A Prison Policy Initiative spokesperson claimed that because the US applies laws unequally, introducing criminal background checks to dating apps would filter out marginalized groups of people. Moreover, public records and court documents often contain erroneous or outdated information.[130] Garbo does not advertise drug possession charges or traffic violations in attempt to combat further marginalization.[131]

Reception[]

Reviews[]

The New York Times wrote that the wide use of Tinder could be attributed not to what Tinder was doing right but to flaws in the models of earlier dating software, which relied on mathematical algorithms to select potential partners. Relationship experts interviewed by the newspaper stated that users used the photographs that come in succession on the app to derive cues as to social status, confidence levels, and personal interests.[11] Marie Claire wrote that the app was "easy to use on the run," "natural," and "addictive" due to the game-style of Tinder, but that "... it's hard to focus," and Tinder "is still very casual sex-focused--many are only on Tinder for a quick hook-up, so if it's a serious relationship you're after this app might not be for you."[132]

In September 2020, Pakistan announced that it would ban five dating apps, including Tinder; this is because Pakistan's government believes that apps are providing immoral/indecent content to users who do not comply with their local laws.[133]

In popular culture[]

Family Guy (season 15) Episode "The Dating Game" parodies the app.[citation needed]

Easy (season 1) Episode "Utopia" involves a married couple who discover Tinder and uses it for a threesome.[134]

Jane The Virgin (season 2) In "Chapter Thirty-Two" Jane wishes to start dating again, and uses a dating app called "Cynder" which is the shows' spinoff of Tinder.[135]

Sideswiped (TV series) In the TV series Sideswiped a woman finds herself single on her 35th birthday, and decides to go on dates with all 252 of her Tinder matches.[136]

Maid (miniseries) Episode "Cashmere" Alex invites a Tinder match over to the house she is cleaning on Thanksgiving.[137]

Natasha Aponte incident[]

In August 2018, Natasha Aponte made headlines after conning dozens of men she had matched with on Tinder to meet her in Union Square, Manhattan at 6pm for a "Live Tinder" dating competition.[138][139][140][141] According to some, they received an unsolicited message from Aponte – inviting them to meet her. Upon arrival, the men discovered that they had been conned into competing for Aponte, who explained that "she was over dating apps and wanted instead for her suitors to participate in a competition."[138][139][140] The stunt was intended to point out the superficiality of online dating apps like Tinder which function on a "hot or not" ideology. Producer Ron Bliss told CBS News that "there's a lot of issues related to the online dating, it's sexist, ableist ... there's a lot of problems."[142]

User behavior[]

Men use dating apps and websites at a higher frequency than women do—measured by frequency of use and number of users both.[143] The first study on swiping strategies, conducted by Queen Mary University in London, reveals that "men tend to like a large proportion of the women they view but receive only a tiny fraction of matches in return—just 0.6 percent".[144] On the contrary, women are much more selective about who they swipe for, but match at a 10% higher rate than males do. The study then went on to analyze the difference in responsivity between males and females—finding that women are more engaged and take longer to craft a response, while men usually send shorter messages, averaging 12 characters in length.[144]

According to University of Texas at Austin psychologist David Buss, "Apps like Tinder and OkCupid give people the impression that there are thousands or millions of potential mates out there. One dimension of this is the impact it has on men's psychology. When there is ... a perceived surplus of women, the whole mating system tends to shift towards short-term dating,"[30] and there is a feeling of disconnect when choosing future partners.[145] In addition, an article written for The Atlantic suggested that the appearance of an abundance of potential partners causes online daters to be less likely to choose a partner and be less satisfied with their choices of partners.[146][147]

In a 2018 article written for The Atlantic, it is mentioned that data released by Tinder itself in 2018 has shown that of the 1.6 billion swipes it records per day, only 26 million results in matches (a match rate of approximately only 1.63%) [147] Also, a Tinder user interviewed anonymously in an article published in the December 2018 issue of The Atlantic estimated that only one in 10 of their matches actually resulted in an exchange of messages with the other user they were matched with, with another anonymous Tinder user saying, "Getting right-swiped is a good ego boost even if I have no intention of meeting someone," leading The Atlantic article author to conclude "Unless you are exceptionally good-looking, the thing online dating may be best at is sucking up large amounts of time."[147]

In August 2015, journalist Nancy Jo Sales wrote in Vanity Fair that Tinder operates within a culture of users seeking sex without relationships.[30] In 2017, the Department of Communications Studies at Texas Tech University conducted a study to see how infidelity was connected to the Tinder app. The experiment was conducted on 550 students from an unnamed university in the Southwestern United States. The students first provided their demographic information and then answered questions regarding Tinder's link to infidelity. The results showed that more than half reported having seen somebody on Tinder who they knew was in an exclusive relationship (63.9%). 73.1% of participants reported that they knew male friends who used Tinder while in a relationship, and 56.1% reported that they had female friends who used Tinder while in a relationship.[148] Psychologists Douglas T. Kenrick, Sara E. Gutierres, Laurie L. Goldberg, Steven Neuberg, Kristin L. Zierk, and Jacquelyn M. Krones have demonstrated experimentally that following exposure to photographs or stories about desirable potential mates, human subjects decrease their ratings of commitment to their current partners.[149][150] David Buss has estimated that approximately 30 percent of the men on Tinder are married.[151]

Before 2012, most online dating services matched people according to their autobiographical information, such as interests, hobbies, future plans, among other things. But the advent of Tinder that year meant that first impressions could play a crucial role. For social scientists studying human courtship behavior, Tinder offers a much simpler environment than its predecessors. In 2016, Gareth Tyson of the Queen Mary University of London and his colleagues published a paper analyzing the behavior of Tinder users in New York City and London. In order to minimize the number of variables, they created profiles of white heterosexual people only. For each sex, there were three accounts using stock photographs, two with actual photographs of volunteers, one with no photos whatsoever, and one that was apparently deactivated. The researchers pointedly only used pictures of people of average physical attractiveness. Tyson and his team wrote an algorithm that collected all the matches' biographical information, liked them all, and then counted the number of returning likes.[152]

They found that men and women employed drastically different mating strategies. Men liked a large proportion of the profiles they viewed, but received returning likes only 0.6% of the time; women were much more selective but received matches 10% of the time. Men received matches at a much slower rate than women. Once they received a match, women were far more likely than men to send a message, 21% compared to 7%, but they took more time before doing so. Tyson and his team found that for the first two-thirds of messages from each sex, women sent them within 18 minutes of receiving a match compared to five minutes for men. Men's first messages had an average of a dozen characters and were typical simple greetings; by contrast, initial messages by women averaged 122 characters.[152]

Tyson and his collaborators found that the male profiles that had three profile pictures received 238 matches while the male profiles with only one profile picture received only 44 matches (or approximately a 5 to 1 ratio). Additionally, male profiles that had a biography received 69 matches while those without it received only 16 matches (or approximately a 4 to 1 ratio). By sending out questionnaires to frequent Tinder users, the researchers discovered that the reason why men tended to like a large proportion of the women they saw was to increase their chances of getting a match. This led to a feedback loop in which men liked more and more of the profiles they saw while women could afford to be even more selective in liking profiles because of a greater probability of a match. The feedback loop's mathematical limit occurs when men like all profiles they see while women find a match whenever they like a profile. It was not known whether some evolutionarily stable strategy has emerged, nor has Tinder revealed such information.[152]

Tyson and his team found that even though the men-to-women ratio of their data set was approximately one, the male profiles received 8,248 matches in total while the female profiles received only 532 matches in total because the vast majority of the matches for both the male and female profiles came from male profiles (with 86 percent of the matches for the male profiles alone coming from other male profiles), leading the researchers to conclude that homosexual men were "far more active in liking than heterosexual women." On the other hand, the deactivated male account received all of its matches from women. The researchers were not sure why this happened.[152]

See also[]

- Timeline of online dating services

- Comparison of online dating services

- Stable marriage problem and the Gale–Shapley algorithm

References[]

- ^ "Match names Renate Nyborg as Tinder CEO". CNBC. 10 September 2021. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "Tinder". Owler. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Abrams, Mike (2016). Sexuality and Its Disorders: Development, Cases, and Treatment. Sage Publications. p. 381. ISBN 9781483309705.

Tinder is a hookup/dating app primarily for the smartphone.

- ^ Karniel, Yuval; Lavie-Dinur, Amit (2015). Privacy and Fame: How We Expose Ourselves across Media Platforms. Lexington Books. p. 118. ISBN 9781498510783.

Tinder is a dating/hook-up app that allows physical, emotional and factual sharing.

- ^ Goodall, Emma (2016). The Autism Spectrum Guide to Sexuality and Relationships. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 134. ISBN 9781784502263.

Hook-up apps – Bumble: Bumble is very similar to Tinder in layout and usage; however, it has one significant difference, which is that men are not able to initiate contact with women.

- ^ "Tinder Users Are Finding More Matches Thanks to Spotify: Popular 'Anthems' Include Songs from The Weeknd and Drake". Tech Times. 2 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Barry Diller Says Tinder Succeeded Because IAC Left Its Founders Alone". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 2021-10-27. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ "Barry Diller's IAC Sued by Tinder Co-Founders for $2 Billion". The Hollywood Reporter. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ Grove, Jennifer Van. "IAC stakes bigger claim over dating app Tinder". CNET. Archived from the original on 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ a b c "Tinder, the Fastest Growing Dating App, Taps an Age Old Truth". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ "Tinder Keeps the Fire Burning | App Annie Blog". App Annie. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ Sun, Leo (Jan 21, 2020). "How Tinder Became the Highest Grossing Mobile App of 2019". Nasdaq.

- ^ "Tinder Revenue and Usage Statistics (2021)". Business of Apps. 2017-08-21. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ "Tinder Rolls Out Video in Profile to More Members Across Europe and Asia". Tinder Newsroom. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ a b c d Crook, Jordan (July 9, 2014). "Burned: The Story Of Whitney Wolfe Vs. Tinder". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- "When Whitney did interviews, she repeatedly asked Sean to let her go by 'co-founder,' claiming that the press would take her more seriously if she had that title, according to people in the office."

- "...after all, she was dating his best friend and they all worked together) and he did, in fact, give in a number of times."

- "Sean knew she wasn’t a founder… we all knew she wasn’t a founder," one source said on the phone. "But he wanted to help her career, and he knew that having female representation in the press could only be a good thing for the company."

- One employee even recounted an instance in which Whitney said that she knew she wasn't supposed to be using "co-founder" in her email signature, but would continue to do so until Sean found out."

- "One employee, who was present in a meeting between Sean and Whitney, says that after the Harper's Bazaar article and a couple of others like it, Sean explained that Whitney should not have been using the term co-founder in the press because it was confusing with the media and internally at Tinder."

- "That same witness says that Whitney sent a series of messages to Sean shortly following the article's publication in which she expresses that she knew she wasn't supposed to be going by co-founder for that article."

- "There's also evidence pointing to the fact that she may have used the term co-founder behind the backs of other founders and against their wishes, which adds even more fog to the situation."

- "Yet, it seems that Whitney was well aware that her use of the term co-founder was for the purposes of doing press for the company and not because she actually co-founded the company."

- ^ Witt, Emily (February 11, 2014). "Love Me Tinder". GQ Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Stampler, Laura (February 6, 2014). "Inside Tinder: Meet the Guys Who Turned Dating Into an Addiction". Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dating App Company Tinder Sued for Sexual Harassment". The Forward. Reuters. July 1, 2014. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ Grigoriadis, Vanessa (October 27, 2014). "Inside Tinder's Hookup Factory". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ "Love me Tinder". GQ Magazine. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- ^ "Co-founder feuds at L.A. tech start-ups show how handshake deals can blow up". Los Angeles Times. March 22, 2015. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Williams, Felicia. "Tinder Wins Best New Startup of 2013 – Crunchies Awards 2013". TechCrunch. AOL. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ Clifford, Catherine (2017-01-06). "How a Tinder founder came up with swiping and changed dating forever". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ Humphrey, Katie (May 5, 2013). "Lust at first photo: Tinder heats up the dating-app scene". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ^ a b "IAC embraces dating sites despite online crush". International New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ a b "How Tinder Is Winning the Mobile Dating Wars". Inc. Archived from the original on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- ^ Aziz Ansari, Eric Klinenberg (2015-06-16). Modern Romance. Penguin. p. 106. ISBN 9780698179967. Archived from the original on 2021-08-16. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- ^ "Tinder's swipe interface gets swiped by other apps". Toronto Star. August 6, 2014. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c Sales, Nancy Jo (August 6, 2015). "Tinder and the Dawn of the 'Dating Apocalypse'". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ Bocknek, Alex (23 September 2018). "6 Swipe Dating Apps: Tinder, Bumble, & More". zoosk.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ Swisher, Kara (2015-08-12). "Tinder Founder Sean Rad Returns as CEO, Replacing Chris Payne". Vox. Archived from the original on 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ "Tinder Dating App More Expensive After Age 28". Refinery29. Archived from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- ^ "Tinder ditches moments". November 11, 2015. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ "Tinder got rid of 'Moments' with yesterday's big update". SlashGear. 2015-11-13. Archived from the original on 2021-08-17. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Plaugic, Lizzie (2015-10-01). "Tinder will now let you 'Super Like' the people you really like". The Verge. Archived from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- ^ "United States : Tinder Completes First Acquisition". Mena Report. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ "U.S. dating apps monthly user market share 2016 l Statistic". Statista. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ a b "Tinder Blazes a Trail For Match Growth". Fool.com. 2016-12-19. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ Crook, Jordan. "Tinder Boost, letting you pay to skip the line, goes live worldwide". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 2017-02-09. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- ^ "Tinder Boost Explained: Price Tag, What It Is & When To Do It". vidaselect.com. 14 September 2018. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Tinder Boost puts you top of the pile for 30 minutes". Engadget. AOL. Archived from the original on 2016-09-28. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ^ Wagner, Kurt (October 19, 2016). "Tinder is opening a Silicon Valley office and plans to double its workforce in the next 18 months". Recode. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ "Introducing More Genders on Tinder". Tinder. 2016-11-15. Archived from the original on 2017-02-07. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- ^ Wagner, Kurt (2016-12-08). "Tinder's Sean Rad is stepping down as CEO to become chairman". Vox. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ "Match Group, Inc. Report on Form 10-K for the Fiscal Year ended December 31, 2018" (PDF). February 28, 2019: 38.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shead, Sam. "Tinder is making more money than any other app on the App Store right now". Insider. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ a b c d e f "Match Group (MTCH) - Market capitalization". companiesmarketcap.com. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ a b Carman, Ashley (2021-03-15). "Tinder will soon let you run a background check on a potential date". The Verge. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ "Introducing Tinder Online – Swipe Anywhere". tinder blog. 2017-03-28. Archived from the original on 2017-06-06. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Tinder introduces its new web app". Deccan Chronicle. 2017-03-29. Archived from the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ "Tinder Online is now available globally". Twitter account from Roderick Hsiao, Tinder tech lead. 2017-09-28. Archived from the original on 2018-05-10. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- ^ "What is Flamite? Wondering why it was shut down? - DatingScout.com".

- ^ Bertoni, Steven. "Tinder Hits $3 Billion Valuation After Match Group Converts Options". Forbes. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ "Tinder becomes top-grossing iOS app after letting people pay to see who likes them". The Verge. Archived from the original on 2018-02-16. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- ^ a b Meyersohn, Nathaniel (2017-11-08). "Tinder Gold is a massive hit". CNNMoney. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ Badkar, Mamta (2017-11-08). "Match shares propelled to all-time high as Tinder shines". Financial Times. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ Wells, Georgia (2021-05-29). "Match Group, Former Employees Spar Over Handling of Sexual-Assault Allegation". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ McCormick, Emily (2018-08-08). "Tinder Sends Match Earnings Blazing Past Estimates". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- ^ "Introducing Tinder U". Tinder Blog. 21 August 2018. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Perez, Sarah (2019-05-10). "Tinder is preparing to launch a lightweight version of its dating app called 'Tinder Lite'". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 2019-05-10. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- ^ "Match Group Reports Second Quarter 2019 Results" (PDF). 2019-08-06. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ^ Nelson, Randy. "Global App Revenue Reached $39 Billion in the First Half of 2019, Up 15% Year-Over-Year". Sensor Tower Blog. Archived from the original on 2020-08-31. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- ^ Carville, Olivia (2019-08-06). "Match Surges Most Ever as Tinder Leads Robust Revenue Growth". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ Palmer, Annie (2019-08-07). "Tinder results add more than $5 billion to Match market cap". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ Shu, Catherine (September 4, 2020). "Tinder's interactive video event 'Swipe Night' will launch in international markets this month". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Is Tinder Safe In 2021? Everything You Need To Know About Tinder Safety". boostmatches.com. 19 February 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Tinder to add panic button and anti-catfishing tech". BBC News. January 24, 2020. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (March 20, 2020). "Tinder is letting everyone swipe around the world for free to find quarantine buddies". The Verge. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Perez, Sarah (August 5, 2020). "Match confirms plans for Tinder Platinum, a new top-level subscription for power users, arriving Q4". Techcrunch. Archived from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Jahangir, Ramsha (16 October 2020). "Pakistan's Tinder ban signals coming showdowns with YouTube and Twitter". Coda Story. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "Pakistan blocks Tinder and Grindr for 'immoral content'". BBC News. 2 September 2020. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Elis-Petersen, Hannah; Meer Baloch, Shah. "This article is more than 7 months old Imran Khan's Tinder and Grindr ban in Pakistan criticised as 'hypocrisy'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ^ "PTA bans five dating apps including Tinder citing 'immoral content'". Dawn. AFP. 1 September 2020. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Hartmans, Avery (November 5, 2020). "People continue to flock to Tinder and Hinge in droves to help fill the social void as the coronavirus stretches through the fall". Business Insider. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Araque, Jacinto. "Tinder, the dating app, to sell phone cases, accessories and apparel under its 'Tinder Made' brand". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 2021-02-23. Retrieved 2021-03-03.

- ^ Chan, Tim (2021-03-19). "Tinder Giving Away Free Covid Testing Kits as People Start Dating IRL Again". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2021-03-23. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (2021-03-15). "Tinder will soon let you run a background check on a potential date". The Verge. Archived from the original on 2021-03-25. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "Tinder to tackle catfishing with ID verification". Sky News. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Jim Lanzone to Join Yahoo as Chief Executive Officer". 10 September 2021. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "Match Appoints Renate Nyborg as Tinder's First Female CEO". Bloomberg.com. 10 September 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ Culliford, Elizabeth (2021-12-02). "Welcome to the Tinderverse: Tinder's CEO talks metaverse, virtual currency". Reuters. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- ^ "From Hookup App to Legitimate Social Network: Can Tinder Make the Jump". Hootsuite Social Media Management. 2014-06-19. Archived from the original on 2015-06-15. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ "Everything you need to know about dating on Tinder (and how Canadians are using it)". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- ^ "Tinder: The Online Dating App Everyone's Talking About". Marie Claire. 2017-11-27. Archived from the original on 2014-07-31. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ Jarvey, Natalie (12 March 2014). "Dating App Tinder to Launch Verification Program for Stars". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Dating App Revenue and Usage Statistics (2021)". Business of Apps. 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ "Tinder Co-Founders' $2 Billion-Plus Legal Battle is Finally Getting Its Day in Court". dot.LA. 2021-10-29. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ "All eyes are on Tinder – Business Insider". Business Insider. July 30, 2015. Archived from the original on August 2, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Till, Jacquelyn (4 August 2015). "Improve Your Tinder Dating with Tinder Apps". Top Mobile Trends. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Tinder launched its paid subscription service today". Business Insider. March 2, 2015. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ "Here's why Tinder's new paid service will cost more if you're old". Fortune. March 2, 2015. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ "Tinder Cost". Healthy Framework. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ "How Many People Use Tinder? [43+ Exceptional Tinder Statistics for 2021]". TechJury. 2020-03-25. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ https://s22.q4cdn.com/279430125/files/doc_financials/2020/ar/Match-Group-2020-Annual-Report-to-Stockholders.pdf

- ^ "Signing Up and Getting Started". Tinder. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Tiffany, Kaitlyn (2019-02-07). "How the Tinder algorithm actually works". Vox. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ "NOPE: People Are Getting Rejected Hundreds Of Millions Of Times On Tinder Every Day". Business Insider. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ McGoogan, Cara (June 9, 2016). "Tinder is banning under 18s – previous limit was 13". Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ "Tinder hookups skyrocketed 300% at Coachella's first weekend". Mashable. April 15, 2015. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ "Answers to everything you want to know about Tinder". Tinder. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ "How Does Tinder Work? What is Tinder?". 2015-11-16. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ "Messaging a Match". 2019-10-03. Archived from the original on 2019-10-03. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "Face to Face Video Chat". Tinder. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ a b Crook, Jordan. "Tinder Cuddles Up To Instagram In Latest Update". Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Bell, Karissa (15 April 2015). "You can now connect Instagram to your Tinder profile". Mashable. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Ong, Thuy (2017-08-29). "Tinder Gold, which lets you pay to see who swiped right on you, arrives in the US". The Verge. Archived from the original on 2017-08-29. Retrieved 2017-08-29.

- ^ "Tinder to add panic button and anti-catfishing tech". BBC News. 2020-01-24. Archived from the original on 2020-01-24. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (2019-07-24). "Tinder will warn users when they travel to countries where LGBTQ relationships are punishable by law". The Verge. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ "Tinder Launches A New Way to Find a "Plus One" Ahead of Busiest Wedding Season in 35 years". Tinder. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Buhr, Sarah. "Tinder Is Going To The Dogs With NYC Puppy Rescue Project". Archived from the original on May 19, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Rescue Campaign Puts 10 Abandoned Dogs on Tinder, Gets 2,700 Matches in a Week". Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Crook, Jordan. "Tinder's First Advertisement Is One Big Experiment". Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Ifeanyi, K. C. (2020-12-09). "Tinder and Megan Thee Stallion will give you $10,000 to stop being so shy in your profile". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ Summers, Nick (July 3, 2014). "The Truth About Tinder and Women Is Even Worse Than You Think". Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ Bercovici, Jeff (July 1, 2014). "IAC Suspends Tinder Co-Founder After Sex Harassment Lawsuit". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "Tinder, former marketing executive settle sexual harassment case". Reuters. 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ O'Brien, Sara Ashley (2018-03-17). "Tinder sues dating app Bumble". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on 2021-02-14. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "Tinder, Bumble Settle Dating App IP War - Law360". www.law360.com. Archived from the original on 2021-08-13. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (December 18, 2018). "Tinder fires its head of comms, following her participation in a $2 billion lawsuit against Match". The Verge. Archived from the original on December 18, 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "Former Tinder Exec Sues Former CEO for Sexual Assault". Fortune. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ Perez, Sarah. "Dating app maker Match sued by FTC for fraud". techcrunch.com. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b Isidore, Laurie Segall and Chris (2018-08-14). "Tinder co-founders and 8 others sue dating app's owners, claiming they're owed $2 billion". CNNMoney. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ Indap, Sujeet (2021-11-01). "Tinder founders go to court over bitter break-up with Barry Diller". Financial Times. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ Gabbatt, Adam (May 28, 2015). "Popularity of 'hookup apps' blamed for surge in sexually transmitted infections". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 4, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Summers, Nick (February 20, 2014). "New Tinder Security Flaw Exposed Users' Exact Locations for Months". Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- ^ Guillén, Beatriz (August 25, 2016). "Spanish engineers find Tinder flaw that reveals users' location". El País. Ediciones El País, S.L.

- ^ Nandwani, Mona; Kaushal, Rishabh (July 2017). Evaluating User Vulnerability to Privacy Disclosures over Online Dating Platforms. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Vol. 612. pp. 342–353. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-61542-4_32. ISBN 978-3-319-61541-7.

- ^ Duportail, Judith (September 26, 2017). "I asked Tinder for my data. It sent me 800 pages of my deepest, darkest secrets". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ Corrigan, Hope (2021-04-13). "Tinder's plan for criminal record checks raises fears of 'lifelong punishment'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (15 March 2021). "Tinder will soon let you run a background check on a potential date". The Verge. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Newall, Sally. "Tinder: The Dating App EVERYONE's Talking About". Marie Claire. Archived from the original on 2014-07-31. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Pakistan blocks 'immoral' Tinder, Grindr and other apps". The Guardian. Reuters. 2020-09-01. Archived from the original on 2020-09-03. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ "Easy S 1 E 6 Utopia / Recap". IMDb. 22 September 2016. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ Viruet, Pilot (2 February 2016). "Jane The Virgin E 32/ Recap". The New York Times. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ "Sideswiped/Recap". Decider. 25 July 2018. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ Wheeler, Greg (2021-10-01). "Maid – Season 1 Episode 4 "Cashmere" Recap & Review". The Review Geek. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ^ a b Bromwich, Jonah Engel (August 20, 2018). "A Bunch of Men Got Tinder-Pranked in Union Square". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Malone Kircher, Madison (August 20, 2018). "An Instagram Model Tinder-Scammed Dozens of Men Into Coming to Union Square to Compete for a Date". New York. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Estes, Adam Clark (August 20, 2018). "Woman Tricks Dozens of Men on Tinder Into Showing Up for Mass Dating Stunt". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Wolfson, Sam (August 21, 2018). "Woman cons dozens of men into 'date' then sets them against each other". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ "Natasha Aponte, woman who tricked thousands of men on Tinder, explains purpose behind dating competition". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ Abramova, Olga & Baumann, Annika & Krasnova, Hanna & Buxmann, Peter. (2016). Gender Differences in Online Dating: What Do We Know So Far? A Systematic Literature Review. 10.1109/HICSS.2016.481. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281965128_Gender_Differences_in_Online_Dating_What_Do_We_Know_So_Far_A_Systematic_Literature_Review Archived 2021-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Tyson, Gareth; Perta, Vasile C.; Haddadi, Hamed; Seto, Michael C. (7 July 2016). "A First Look at User Activity on Tinder". arXiv:1607.01952 [cs.SI].

- ^ "Tinder and the controversy it creates". madison.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ Slater, Dan (January 2013). "A Million First Dates". The Atlantic. Emerson Collective. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c Julian, Kate (December 2018). "Why Are Young People Having So Little Sex?". The Atlantic. Emerson Collective. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ Weiser, Dana A.; Niehuis, Sylvia; Flora, Jeanne; Punyanunt-Carter, Narissra M.; Arias, Vladimir S.; Baird, R. Hannah (2017), "Swiping right: Sociosexuality, intentions to engage in infidelity, and infidelity experiences on Tinder", Personality and Individual Differences, 133: 29–33, doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.025, S2CID 149210515

- ^ Kenrick, Douglas; Gutierres, Sara E.; Goldberg, Laurie L. (1989). "Influence of erotica on ratings of strangers and mates". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Elsevier. 25 (2): 159–167. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(89)90010-3.

- ^ Kenrick, Douglas T.; Neuberg, Steven L.; Zierk, Kristin L.; Krones, Jacquelyn M. (1994). "Evolution and Social Cognition: Contrast Effects as a Function of Sex, Dominance, and Physical Attractiveness". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. SAGE Publications. 20 (2): 210–217. doi:10.1177/0146167294202008. S2CID 146625806. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Buss, David M. (2016) [1994]. The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating (3rd ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 163. ISBN 978-0465097760.

- ^ a b c d "How Tinder 'Feedback Loop' Forces Men and Women into Extreme Strategies". Tech Policy. MIT Technology Review. July 15, 2016. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

External links[]

- Computer-related introductions in 2012

- Geosocial networking

- IAC (company)

- Mobile social software

- Online dating services of the United States

- Proprietary cross-platform software

- Online dating applications