To Be or Not to Be (1942 film)

| To Be or Not to Be | |

|---|---|

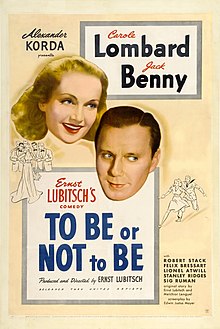

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ernst Lubitsch |

| Written by | Melchior Lengyel Edwin Justus Mayer Ernst Lubitsch (uncredited) |

| Produced by | Ernst Lubitsch |

| Starring | Carole Lombard Jack Benny Robert Stack Felix Bressart Sig Ruman |

| Cinematography | Rudolph Maté |

| Edited by | Dorothy Spencer |

| Music by | Werner R. Heymann Uncredited: Miklós Rózsa |

Production company | Romaine Film Corp.[1] |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | |

Running time | 99 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.2 million[4] |

| Box office | $1.5 million (US rentals)[5] |

To Be or Not to Be is a 1942 American black comedy film directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring Carole Lombard, Jack Benny, Robert Stack, Felix Bressart, Lionel Atwill, Stanley Ridges and Sig Ruman. The plot concerns a troupe of actors in Nazi-occupied Warsaw who use their abilities at disguise and acting to fool the occupying troops. It was adapted by Lubitsch (uncredited) and Edwin Justus Mayer from the story by Melchior Lengyel.[6] The film was released one month after actress Carole Lombard was killed in an airplane crash.[7] In 1996, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[8][9]

The title is a reference to the famous "To be, or not to be" soliloquy in William Shakespeare's Hamlet.[10]

Plot[]

The well-known stars of a Warsaw theater company, including "ham" actor Josef Tura and wife Maria, are rehearsing "Gestapo", a Nazi satirical play. That night, when the company is performing Hamlet, with Tura in the title role, one of the actors, Bronski, commiserates with colleague Greenberg about being limited to being spear carriers. Greenberg, who is implied to be Jewish, reveals he has always dreamed of playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice.

Maria meets pilot Lieutenant Stanislav Sobinski, while Tura begins his "To be or not to be..." speech. Soon, the government orders to cancel "Gestapo" to avoid possibly worsening relations with Germany. The following night, after a brief assignation, Sobinski walks out during "To be or not to be", infuriating Tura. Sobinski confesses his love to Maria, assuming that she will leave her husband, as well as the stage, to be with him. Before Maria can correct Sobinski's assumption, news breaks out that Germany has invaded Poland. Sobinski leaves to join the fight at the Polish division of the Royal Air Force (RAF), and the actors hide as Warsaw is bombed.

Sobinski and his fellows meets the Polish resistance leader Professor Siletsky. Siletsky will return to Warsaw soon, and the men give him messages for their loved ones. However, Sobinski becomes suspicious when Siletsky doesn't know of Maria or Tura. The Allies realize that Siletsky has the identity of the relatives of Polish airmen in the RAF, against whom reprisals can be taken. Sobinski flies back to warn Maria, however Siletsky has Maria brought to him by German soldiers. He invites Maria to dinner, hoping to recruit her as a spy. Just before she arrives home, Tura returns and finds Sobinski in his bed. Maria and Sobinski try to figure out what to do about Siletsky, while Tura tries to figure out what is going on with his wife and the pilot. Tura proclaims that he will kill Siletsky.

Later, a member of the company disguised as Gestapo summons Siletsky to "Gestapo headquarters", the theatre. Tura pretends to be Colonel Ehrhardt of the Gestapo. Siletsky reveals Sobinski's message for Maria, and that "To be or not to be" signals their rendezvous. Tura uncontrollably reveals himself. Siletsky tries to escape but is shot and killed by Sobinski. Tura disguises as Siletsky, destroying his extra copy of the information to confront Maria about her affair. He meets Ehrhardt's adjutant, Captain Schultz, and taken to meet him. Tura passes himself off, and names recently executed prisoners as the leaders of the resistance. Just as Tura is about to leave the theater, several actors yank off Tura's props upon Maria's request, and pretend to drag him out. Everyone is safe, but cannot leave Poland as planned on the plane Ehrhardt had arranged for Siletsky.

The Germans stage a show to honor Hitler during his visit. The actors slip into the theater dressed as Germans and hide until Hitler and his entourage arrive and take their seats. As the Germans are singing the Deutschlandlied, Greenberg suddenly appears and rushes Hitler's box, causing enough distraction to exchange the actors for the real Germans. Acting as the head of Hitler's guard, Tura demands to know what Greenberg wants, giving the actor his chance to deliver Shylock's speech, ending with "if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?!" Tura orders Greenberg to be "taken away"; all the actors march out, get in Hitler's cars and drive away.

At her apartment, Maria waits for the company, as they all intend to leave. Bronski enters costumed as Hitler, then walks out speechless, alarmed that he catches Ehrhardt trying to seduce Maria, Hitler's mistress. Maria dashes after Bronski calling "mein fuhrer," but Ehrhardt shoots himself.

The actors take off on Hitler's plane. Sobinski flies to Scotland, where the actors are interviewed by the press. Asked what reward Tura would like for saving the underground movement, Maria asserts that Josef wants to play Hamlet. While performing, Tura is relieved to see Sobinski sitting quietly in the audience at the critical moment of his soliloquy. But as he proceeds, a handsome new officer gets up and heads noisily backstage.

Cast[]

- Carole Lombard as Maria Tura, an actress in Nazi-occupied Poland

- Jack Benny as Joseph Tura, an actor and Maria's husband

- Robert Stack as Lt. Stanislav Sobinski, a Polish airman in love with Maria

- Felix Bressart as Greenberg, a Jewish member of the company who plays bit parts and dreams of playing Shylock

- Lionel Atwill as Rawich, a ham actor in the company

- Stanley Ridges as Professor Alexander Siletsky, a Nazi spy masquerading as a Polish resistance worker

- Sig Ruman as Col. Ehrhardt, the bumbling Gestapo commander in Warsaw

- Tom Dugan as Bronski, a member of the company who impersonates Hitler

- Charles Halton as Dobosh, the producer of the company

- George Lynn as Actor-Adjutant, a member of the company who masquerades as Col. Ehrhardt's adjutant

- Henry Victor as Capt. Schultz, the real adjutant of Col. Ehrhardt

- Maude Eburne as Anna, Maria's maid

- Halliwell Hobbes as Gen. Armstrong, a British intelligence officer

- Miles Mander as Major Cunningham, a British intelligence officer

- James Finlayson as Scottish Farmer (uncredited)

- Olaf Hytten as Polonius in Warsaw (uncredited)

- Maurice Murphy as Polish RAF Pilot (uncredited)

- Frank Reicher as Polish Official (uncredited)

Production[]

Lubitsch had never considered anyone other than Jack Benny for the lead role in the film. He had even written the character with Benny in mind. Benny, thrilled that a director of Lubitsch's caliber had been thinking of him while writing it, accepted the role immediately. Benny was in a predicament as, strangely enough, his success in the film version of Charley's Aunt (1941) was not interesting anyone in hiring the actor for their films.

For Benny's costar, the studio and Lubitsch decided on Miriam Hopkins, whose career had been faltering in recent years. The role was designed as a comeback for the veteran actress, but Hopkins and Benny did not get along well, and Hopkins left the production.

Lubitsch was left without a leading lady until Carole Lombard, hearing his predicament, asked to be considered.[11] Lombard had never worked with the director and yearned to have an opportunity. Lubitsch agreed and Lombard was cast. The film also provided Lombard with an opportunity to work with friend Robert Stack, whom she had known since he was an awkward teenager. The film was shot at United Artists, which allowed Lombard to say that she had worked at every major studio in Hollywood.

Reception[]

To Be or Not To Be, now regarded as one of the best films of Lubitsch's, Benny's and Lombard's careers, was initially not well received by the public, many of whom could not understand the notion of making fun out of such a real threat as the Nazis. According to Jack Benny's unfinished memoir, published in 1991, his own father walked out of the theater early in the film, disgusted that his son was in a Nazi uniform, and vowed not to set foot in the theater again. Benny convinced him otherwise and his father ended up loving the film, and saw it forty-six times.[12]

The same could not be said for all critics. While they generally praised Lombard, some scorned Benny and Lubitsch and found the film to be in bad taste. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote that it was "hard to imagine how any one can take, without batting an eye, a shattering air raid upon Warsaw right after a sequence of farce or the spectacle of Mr. Benny playing a comedy scene with a Gestapo corpse. Mr. Lubitsch had an odd sense of humor—and a tangled script—when he made this film."[13] The Philadelphia Inquirer agreed, calling the film "a callous, tasteless effort to find fun in the bombing of Warsaw."[14] Some critics were especially offended by Colonel Ehrhardt's line: "Oh, yes I saw him [Tura] in 'Hamlet' once. What he did to Shakespeare we are now doing to Poland."[14]

However, other reviews were positive. Variety called it one of Lubitsch's "best productions in [a] number of years ... a solid piece of entertainment."[15] Harrison's Reports called it "An absorbing comedy-drama of war time, expertly directed and acted. The action holds one in tense suspense at all times, and comedy of dialogue as well as of acting keeps one laughing almost constantly."[16] John Mosher of The New Yorker also praised the film, writing, "That comedy could be planted in Warsaw at the time of its fall, of its conquest by the Nazis, and not seem too incongruous to be endured is a Lubistch triumph."[17]

In 1943, the critic Mildred Martin reviewed another of Lubitsch's films in The Philadelphia Inquirer and referred derogatively to his German birth and his comedy about Nazis in Poland. Lubitsch responded by publishing an open letter to the newspaper in which he wrote,

What I have satirized in this picture are the Nazis and their ridiculous ideology. I have also satirized the attitude of actors who always remain actors regardless of how dangerous the situation might be, which I believe is a true observation. It can be argued if the tragedy of Poland realistically portrayed as in To Be or Not to Be can be merged with satire. I believe it can be and so do the audience which I observed during a screening of To Be or Not to Be; but this is a matter of debate and everyone is entitled to his point of view, but it is certainly a far cry from the Berlin-born director who finds fun in the bombing of Warsaw.[14][18]

In recent times the film has become recognized as a comedy classic. To Be or Not To Be has a 96% approval rating on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes with an average rating of 8.7/10, based on 47 reviews, with the consensus: "A complex and timely satire with as much darkness as slapstick, Ernst Lubitsch's To Be or Not To Be delicately balances humor and ethics."[19] Slovenian cultural critic and philosopher, Slavoj Žižek named it his favourite comedy, in an interview in 2015, where he remarked, "It is madness, you can not do a better comedy I think".[20]

Awards and honors[]

To Be or Not to Be was nominated for one Academy Award: the Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #49[21]

Remakes[]

- A radio drama adaptation of To Be or Not to Be was produced by the Screen Guild Theatre on Jan. 18, 1943, starring William Powell and Diana Lewis.

- The film was remade as To Be or Not to Be in 1983. It was directed by Alan Johnson featuring Mel Brooks and Anne Bancroft.

- A stage adaptation was written in German by Juergen Hoffmann in 1988.

- A Bollywood version, Maan Gaye Mughal-e-Azam was released in 2008.

- A stage version also titled To Be or Not to Be opened on Broadway in 2008.

- A stage adaptation was created in Budapest, Hungary by Marton László, Radnóti Zsuzsa, and Deres Péter in 2011.[22]

References[]

- ^ To Be or Not to Be at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ "Motion Picture Daily Feb 4, 1942".

- ^ "Variety Feb 18, 1942".

- ^ Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists: The Company Built by the Stars. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-23004-3. p173

- ^ "Variety (January 1943)". New York, NY: Variety Publishing Company. June 14, 1943 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "To Be or Not to Be | BFI | BFI". Explore.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-07-11. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ^ "To Be or Not to Be (1942) - Notes". TCM.com. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ^ "National Film Registry (National Film Preservation Board, Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. 2013-11-20. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- ^ To be, or not to be

- ^ "Detail view of Movies Page". Afi.com. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ^ Jack Benny and Joan Benny, Sunday Nights at Seven: The Jack Benny Story, G.K. Hall, 1991, p. 232

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (March 7, 1942). "Movie Review - To Be or Not to Be". The New York Times. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Insdorf, Annette (2003). Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust (Third ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780521016308.

- ^ "Film Reviews". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc. February 18, 1942. p. 8.

- ^ "'To Be or Not to Be' with Carole Lombard, Jack Benny and Robert Stack". Harrison's Reports: 35. February 28, 1942.

- ^ Mosher, John (March 14, 1942). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Corp. p. 71.

- ^ Weinberg, Herman (1977). The Lubitsch Touch: A Critical Study. Dover Publications. p. 246.

- ^ ""Rotten Tomatoes"".

- ^ Film, in; May 25th, Philosophy; Comment, 2017 Leave a. "Slavoj Žižek Names His 5 Favorite Films".

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- ^ ""Lenni vagy nem lenni"". Archived from the original on 2013-04-28.

Further reading[]

- Eyman, Scott Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise p. 302

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: To Be or Not to Be (1942 film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to To Be or Not to Be (1942 film). |

- To Be or Not to Be essay [1] by David L. Smith at National Film Registry

- To Be or Not to Be essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 349-350

- To Be or Not to Be at IMDb

- To Be or Not to Be at AllMovie

- To Be or Not to Be at the TCM Movie Database

- To Be or Not to Be at the American Film Institute Catalog

- To Be or Not to Be at Rotten Tomatoes

- To Be or Not to Be (1942) Movie stills and literature

- To Be or Not to Be on Screen Guild Theater: January 18, 1943

- To Be or Not to Be: The Play’s the Thing an essay by Geoffrey O'Brien at the Criterion Collection

- 1942 films

- English-language films

- 1940s black comedy films

- 1942 comedy-drama films

- 1940s screwball comedy films

- American comedy-drama films

- American screwball comedy films

- American films

- American black-and-white films

- American political satire films

- American black comedy films

- Films about actors

- Films about theatre

- Films directed by Ernst Lubitsch

- Films set in Warsaw

- Films set in 1939

- Military humor in film

- Films based on works by William Shakespeare

- United States National Film Registry films

- United Artists films

- World War II films made in wartime

- Films scored by Miklós Rózsa

- Cultural depictions of Adolf Hitler