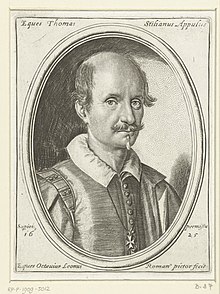

Tommaso Stigliani

Tommaso Stigliani | |

|---|---|

Tommaso Stigliani | |

| Born | 1573 Matera, Kingdom of Naples |

| Died | 1651 Rome, Papal States |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | Italian |

| Nationality | Napoletano |

| Period | Late Middle Ages |

| Literary movement | Baroque |

| Notable works | Il mondo nuovo Dello occhiale |

Tommaso Stigliani (1573–1651) was an Italian poet, literary critic, and writer.

Biography[]

He was born in Matera, and educated in Naples where he met with the poets Torquato Tasso and Giambattista Marino. With the latter, Stigliani started a lifelong polemic and argument. Especially in Dello occhiale (Venice: Carempello, Sandro Bazacchi, 1627), Stigliani laments Marino's many “failures” in the poem Adone. Marino refused, Stigliani indignantly points out, to follow Aristotle's unities, ignoring the need for a proper beginning, middle, and an end. The poem is overwhelmed by superfluities, enthusiasms, and disproportion. In chapter 6, Stigliani regrets the way Marino “stumbles” through the episodes of Adonis and Venus. And so on, for more than 500 pages (there are tables at the end that list all of Marino's “errors”).[1]

Stigliani's contentious personality led him initially to seek employment in various courts of Northern Italy, including Parma, where he was employed by the Duke. But ultimately had to remove himself to Rome where he published a volume of his works, mainly romantic sonnets, in Canzoniero dato in luce da Balducci (1625, Rome). He had already published Il Mondo Nuovo (1617, Piacenza), an epic poem about the discovery of America. In his depiction, Stigliani merges a detailed description of America with characters and situations that are closer to the realities of life in Europe in the 1600s, creating a bridge between the two continents. Stigliani’s America is an allegory of the old world and the poet used it to construct a critique of the society of the day. The description of the newt that lives in the Rio de la Plata is a way to make fun of his competitor Giambattista Marino; the execution of the amazons in the poem is a criticism of the behavior of his patron Ranuccio Farnese; the mad people of the island of Brandana mirror the behavior of all the princes and courtiers who occupy every European Renaissance court. And since it is a poem, the shrewd poet can always defend himself by saying that the Mondo nuovo is, in part, a fictional work. According to Stigliani, the new world with all its faults such as cannibalism and the freedom of sexual mores is, despite everything, better than the corruption and flaws which he finds in his contemporary Europe.

Tommaso Stigliani died in Rome and his letters were published posthumously in 1661.[2]

Works[]

- Stigliani, Tommaso (1600). Il Polifemo. Milano. nella stampa del q. Pacifico Pontio impressore archiepiscopale. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Stigliani, Tommaso (1617). Il mondo nuovo (1 ed.). Piacenza. per Alessandro Bazacchi. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Stigliani, Tommaso (1628). Il mondo nuovo (2 ed.). Roma. Appresso . Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Stigliani, Tommaso (1623). Il canzoniero del signor caualier fra' Tomaso Stigliani. Roma. per l'erede di Bartolomeo Zannetti. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Stigliani, Tommaso (1627). Dello occhiale opera difensiua del caualier fr. Tomaso Stigliani. Scritta in risposta al caualier Gio. Battista Marini. Dedicato all'eccellentiss. sig. conte D'Oliuares. Venezia. appresso Pietro Carampello. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Stigliani, Tommaso (1651). Lettere del caualiere fra Tomaso Stigliani dedicate al sig. prencipe di Gallicano. Roma. per Domenico Manelfi. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

Bibliography[]

- Mary A. Watt (2011). ""Cosmopoiesis": Dante, Columbus and Spiritual Imperialism in Stigliani's "Mondo nuovo"". MLN. 127 (1): S245–S256. JSTOR 41415866.

References[]

- ^ Hyde Minor, Vernon (2006). The Death of the Baroque and the Rhetoric of Good Taste. Cambridge University Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780521843416.

- ^ Dizionario biografico universale, Volume 5, by Felice Scifoni, Publisher Davide Passagli, Florence (1849); page 191.

- 1573 births

- 1651 deaths

- 17th-century Italian writers

- Italian poets

- People from Matera