Trans-Saharan slave trade

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

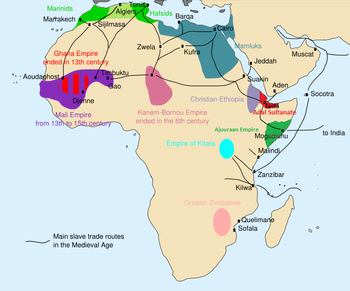

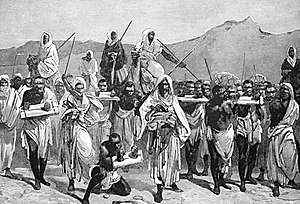

During the Trans-Saharan slave trade, slaves from West Africa were transported across the Sahara desert to North Africa to be sold to Mediterranean and Middle eastern civilizations. It was part of the Trans-Saharan trade.[1][2]

Early trans-Saharan slave trade[]

The Garamantes relied heavily on slave labor from sub-Saharan Africa.[3] They used slaves in their own communities to construct and maintain underground irrigation systems known to Berbers as foggara.[4] Ancient Greek historian Herodotus recorded in the 5th century BC that the Garemantes enslaved cave-dwelling Ethiopians, known as Troglodytae, chasing them with chariots.[5]

In the early Roman Empire, the city of Lepcis established a slave market to buy and sell slaves from the African interior.[6] The empire imposed customs tax on the trade of slaves.[6] In 5th century AD, Roman Carthage was trading in black slaves brought across the Sahara.[7] Black slaves seem to have been valued as household slaves for their exotic appearance.[7] Some historians argue that the scale of slave trade in this period may have been higher than medieval times due to the high demand for slaves in the Roman Empire.[7]

Prisoners of war were a regular occurrence in the ancient Nile Valley and Africa. During times of conquest and after winning battles, the ancient Nubians were taken as slaves by the ancient Egyptians .[8] In turn, the ancient Egyptians took slaves after winning battles with the Libyans, Canaanites, and Nubians.[9]

Trans-Saharan slave trade in the Middle Ages[]

The trans-Saharan slave trade, established in Antiquity,[10] continued during the Middle Ages. Following its 8th-century conquest of North Africa, Arabs, Berbers and other ethnic groups ventured into Sub-Saharan Africa first along the Nile Valley towards Nubia, and also across the Sahara towards West Africa. They were interested in the trans-Saharan trade, especially in slaves.

The slaves brought from across the Sahara were mainly used by wealthy families as domestic servants,[11] and concubines.[12] Some served in the military forces of Egypt and Morocco.[12][13] In 641 during the Baqt, a treaty between the Nubian Christian state of Makuria and the new Muslim rulers of Egypt, the Nubians agreed to give Muslim traders more privileges of trade in addition to a share in their slave trading.[14] The Bornu Empire in the eastern part of Niger was also an active part of the trans-Saharan slave trade for hundreds of years.

In 1416, al-Maqrizi told how pilgrims coming from Takrur (near the Senegal River) brought 1,700 slaves with them to Mecca. In North Africa, the main slave markets were in Morocco, Algiers, Tripoli and Cairo. Sales were held in public places or in souks. After Europeans had settled in the Gulf of Guinea, the trans-Saharan slave trade became less important.[citation needed]

Ibn Battuta who visited the ancient African kingdom of Mali in the mid-14th century recounts that the local inhabitants vie with each other in the number of slaves and servants they have, and was himself given a slave boy as a "hospitality gift."[15]

Arabs were sometimes made into slaves in the trans-Saharan slave trade.[16][17] Sometimes castration was done on Arab slaves. In Mecca, Arab women were sold as slaves according to Ibn Butlan, and certain rulers in West Africa had slave girls of Arab origin.[18][19] According to al-Maqrizi, slave girls with lighter skin were sold to West Africans on hajj.[20][21][22] Ibn Battuta met an Arab slave girl near Timbuktu in Mali in 1353. Battuta wrote that the slave girl was fluent in Arabic, from Damascus, and her master's name was Farbá Sulaymán.[23][24][25] Besides his Damascus slave girl and a secretary fluent in Arabic, Arabic was also understood by Farbá himself.[26] The West African states also imported highly trained slave soldiers.[27]

Late trans-Saharan slave trade[]

In Central Africa during the 16th and 17th centuries, slave traders began to raid the region as part of the expansion of the Saharan and Nile River slave routes. Their captives were enslaved and shipped to the Mediterranean coast, Europe, Arabia, the Western Hemisphere, or to the slave ports and factories along the West and North Africa coasts or South along the Ubanqui and Congo rivers.[28][29]

The Tuareg and others who are indigenous to Libya facilitated, taxed and partly organized the trade from the south along the trans-Saharan trade routes. In the 1830s – a period when slave trade flourished – Ghadames was handling 2,500 slaves a year.[30] Even though the slave trade was officially abolished in Tripoli in 1853, in practice it continued until the 1890s.[31]

The British Consul in Benghazi wrote in 1875 that the slave trade had reached an enormous scale and that the slaves who were sold in Alexandria and Constantinople had quadrupled in price. This trade, he wrote, was encouraged by the local government.[31] writes in an article published in 1911 that: "...it has been said that slave traffic is still going on on the Benghazi-Wadai route, but it is difficult to test the truth of such an assertion as, in any case, the traffic is carried on secretly".[32] At Kufra, the Egyptian traveller Ahmed Hassanein Bey found out in 1916 that he could buy a girl slave for five pounds sterling while in 1923 he found that the price had risen to 30 to 40 pounds sterling.[33] Another traveler, the Danish convert to Islam Knud Holmboe, crossed the Italian Libyan desert in 1930, and was told that slavery is still practiced in Kufra and that he could buy a slave girl for 30 pounds sterling at the Thursday slave market.[33] According to James Richardson's testimony, when he visited Ghadames, most slaves were from Bornu.[34] According to Raëd Bader, based on estimates of the Trans-Saharan trade, between 1700 and 1880 Tunisia received 100,000 black slaves, compared to only 65,000 entering Algeria, 400,000 in Libya, 515,000 in Morocco and 800,000 in Egypt.[35]

Abolition[]

After the establishment of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 to fight slave trading in the Mediterranean, Ahmad I ibn Mustafa, Bey of Tunis, agreed to outlaw exporting, importing, and selling slaves in 1842, and he made slavery illegal in 1846.[37] In 1848, France outlawed slavery in Algeria.[37] Slavery was not abolished in Mauritania until 1981.[37]

Slavery in the post-Gaddafi Libya[]

Since the United Nations-backed and NATO-led overthrow of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi's regime in 2011, Libya has been plagued by disorder and migrants with little cash and no papers have become vulnerable. Libya is a major exit point for African migrants heading to Europe. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) published a report in April 2017 showing that many of the migrants from West-Africa heading to Europe are sold as slaves after being detained by people smugglers or militia groups. African countries south of Libya were targeted for slave trading and transferred to Libyan slave markets instead. According to the victims, the price is higher for migrants with skills like painting and tiling.[38][39] Slaves are often ransomed to their families and in the meantime until ransom can be tortured, forced to work, sometimes to death and eventually executed or left to starve if they can't pay for too long. Women are often raped and used as sex slaves and sold to brothels and private Libyan clients.[38][39][40][41] Many child migrants also suffer from abuse and child rape in Libya.[42][43]

After receiving unverified CNN video of a November 2017 slave auction in Libya, a human trafficker told Al-Jazeera (a Qatari TV station with interests in Libya) that hundreds of migrants are bought and sold across the country every week.[44] Migrants who have gone through Libyan detention centres have shown signs of many human rights abuses such as severe abuse, including electric shocks, burns, lashes and even skinning, stated the director of health services on the Italian island of Lampedusa to Euronews.[45]

A Libyan group known as the Asma Boys have antagonized migrants from other parts of Africa from at least as early as 2000, destroying their property.[46] Nigerian migrants in January 2018 gave accounts of abuses in detention centres, including being leased or sold as slaves.[47] Videos of Sudanese migrants being burnt and whipped for ransom, were released later on by their families on social media.[48] In June 2018, the United Nations applied sanctions against four Libyans (including a Coast Guard commander) and two Eritreans for their criminal leadership of slave trade networks.[49]

Routes[]

According to professor Ibrahima Baba Kaké there were four main slavery routes to north Africa, from east to west of Africa, from the Maghreb to the Sudan, from Tripolitania to central Sudan and from Egypt to the Middle East.[50] Caravan trails, set up in the 9th century, went past the oasis of the Sahara; travel was difficult and uncomfortable for reasons of climate and distance. Since Roman times, long convoys had transported slaves as well as all sorts of products to be used for barter.

Towns and ports involved[]

|

|

See also[]

- Trans-Sahara Highway

- Trans-Saharan trade

- Slavery in ancient Egypt

- Slavery in ancient Rome

- Slavery in Africa

- Slavery in Libya

- Human trafficking in Chad

- Slavery in Mali

- Slavery in Mauritania

- Slavery in Niger

- Slavery in Nigeria

References[]

- ^ Keith R. Bradley. "Apuleius and the sub-Saharan slave trade". Apuleius and Antonine Rome: Historical Essays. p. 177.

- ^ Andrew Wilson. "Saharan Exports to the Roman World". Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. p. 192–3.

- ^ "Fall of Gaddafi opens a new era for the Sahara's lost civilisation". the Guardian. 5 November 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ David Mattingly. "The Garamantes and the Origins of Saharan Trade". Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. p. 27–28.

- ^ Austen, R. (2015). Regional study: Trans-Saharan trade. In C. Benjamin (Ed.), The Cambridge World History (The Cambridge World History, pp. 662-686). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139059251.026

- ^ Jump up to: a b Keith R. Bradley. "Apuleius and the sub-Saharan slave trade". Apuleius and Antonine Rome: Historical Essays. p. 177.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Andrew Wilson. "Saharan Exports to the Roman World". Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. p. 192–3.

- ^ Redford, D. B..From Slave to Pharaoh: The Black Experience of Ancient Egypt. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. Project MUSE

- ^ "Ancient Egypt: Slavery, its causes and practice". Reshafim.org.il. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Andrew Wilson. "Saharan Exports to the Roman World". Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. p. 192–3.

- ^ "Ibn Battuta's Trip: Part Twelve – Journey to West Africa (1351–1353)". Archived from the original on 9 June 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ralph A. Austen. Trans-Saharan Africa in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 31.

- ^ "The impact of the slave trade on Africa".

- ^ Jay Spaulding. "Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World: A Reconsideration of the Baqt Treaty," International Journal of African Historical Studies XXVIII, 3 (1995)

- ^ Noel King (ed.), Ibn Battuta in Black Africa, Princeton 2005, p. 54.

- ^ Muhammad A. J. Beg, The "serfs" of Islamic society under the Abbasid regime, Islamic Culture, 49, 2, 1975, p. 108

- ^ Owen Rutter (1986). The pirate wind: tales of the sea-robbers of Malaya. Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780195826913.

- ^ W. G. Clarence-Smith (2006). Islam and the Abolition of Slavery. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-19-522151-0.

- ^ Humphrey J. Fisher (1 August 2001). Slavery in the History of Muslim Black Africa. NYU Press. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-0-8147-2716-4.

- ^ Chouki El Hamel (27 February 2014). Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-1-139-62004-8.

- ^ Shirley Guthrie (1 August 2013). Arab Women in the Middle Ages: Private Lives and Public Roles. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-764-3.

- ^ William D. Phillips (1985). Slavery from Roman Times to the Early Transatlantic Trade. Manchester University Press. pp. 126–. ISBN 978-0-7190-1825-1.

- ^ Ibn Batuta; Said Hamdun; Noel Quinton King (March 2005). Ibn Battuta in Black Africa. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-55876-336-4.

- ^ Ibn Battuta (1 September 2004). Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354. Psychology Press. pp. 334–. ISBN 978-0-415-34473-9.

- ^ Raymond Aaron Silverman (1983). History, art and assimilation: the impact of Islam on Akan material culture. University of Washington. p. 51.

- ^ Noel Quinton King (1971). Christian and Muslim in Africa. Harper & Row. p. 22. ISBN 9780060647094.

- ^ Ralph A. Austen. Trans-Saharan Africa in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 31.

- ^ International Business Publications, USA (7 February 2007). Central African Republic Foreign Policy and Government Guide (World Strategic and Business Information Library). 1. Int'l Business Publications. p. 47. ISBN 978-1433006210. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Alistair Boddy-Evans. Central Africa Republic Timeline – Part 1: From Prehistory to Independence (13 August 1960), A Chronology of Key Events in Central Africa Republic. About.com

- ^ K. S. McLachlan, "Tripoli and Tripolitania: Conflict and Cohesion during the Period of the Barbary Corsairs (1551-1850)", Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 3, No. 3, Settlement and Conflict in the Mediterranean World. (1978), pp. 285-294.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lisa Anderson, "Nineteenth-Century Reform in Ottoman Libya", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 16, No. 3. (Aug., 1984), pp. 325-348.

- ^ Adolf Vischer, "Tripoli", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 38, No. 5. (Nov., 1911), pp. 487-494.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wright, John (2007). The trans-Saharan slave trade. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-38046-4.

- ^ Wright, John (1989). Libya, Chad and the Central Sahara. C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. ISBN 1-85065-050-0.

- ^ (in French) Raëd Bader, Noirs en Algérie, XIXe-XXe siècles, éd. École normale supérieure de Lyon, 20 June 2006

- ^ "Le Petit Parisien. Supplément littéraire illustré". Gallica. 2 June 1907. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c El Hamel, Chouki (2012). Black Morocco : a History of Slavery, Race, and Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-61632-4. OCLC 823724244.

- ^ Jump up to: a b African migrants sold in Libya 'slave markets', IOM says. BBC.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Migrants from west Africa being 'sold in Libyan slave markets'". The Guardian.

- ^ "African migrants sold as 'slaves' in Libya".

- ^ "West African migrants are kidnapped and sold in Libyan slave markets / Boing Boing". boingboing.net.

- ^ Adams, Paul (28 February 2017). "Libya exposed as child migrant abuse hub" – via www.bbc.com.

- ^ "Immigrant Women, Children Raped, killed and Starved in Libya's Hellholes: Unicef". 28 February 2017.

- ^ "African refugees bought, sold and murdered in Libya". Al-Jazeera.

- ^ "Exclusive: Italian doctor laments Libya's 'concentration camps' for migrants". Euronews. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Africa Research Bulletin: Economic, financial, and technical series, Volume 37. Blackwell. 2000. p. 14496. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "'Used as a slave' in a Libyan detention centre". 2 January 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2019 – via www.BBC.com.

- ^ Elbagir, Nima; Razek, Raja; Sirgany, Sarah; Tawfeeq, Mohammed. "Migrants beaten and burned for ransom". CNN. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Elbagir, Nima; Said-Moorhouse, Laura (7 June 2018). "Unprecedented UN sanctions slapped on 'millionaire migrant traffickers'". CNN. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Doudou Diène (2001). From Chains to Bonds: The Slave Trade Revisited. Berghahn Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1571812650. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

Further reading[]

- History of the Sahara

- Trade routes

- History of North Africa

- African slave trade

- Slavery in Asia

- Slavery in Libya