Tremolo

In music, tremolo (Italian pronunciation: [ˈtrɛːmolo]), or tremolando ([tremoˈlando]), is a trembling effect. There are two types of tremolo.

The first is a rapid reiteration:

- of a single note, particularly used on bowed string instruments, by rapidly moving the bow back and forth; plucked strings such as on a harp, where it is called bisbigliando (Italian pronunciation: [bizbiʎˈʎando]) or "whispering"; and tremolo picking, in which a single note is repeated extremely rapidly with a plectrum (or "pick") on traditionally plucked string instruments such as guitar (although a pick is not necessary to execute a tremolo), mandolin, etc.

- between two notes or chords in alternation, an imitation (not to be confused with a trill) of the preceding that is more common on keyboard instruments. Mallet instruments such as the marimba are capable of either method.

- a roll on any percussion instrument, whether tuned or untuned.

A second type of tremolo is a variation in amplitude:

- as produced on organs by tremulants

- using electronic effects in guitar amplifiers and effects pedals which rapidly turn the volume of a signal up and down, creating a "shuddering" effect

- an imitation of the same by strings in which pulsations are taken in the same bow direction

- a vocal technique involving a wide or slow vibrato, not to be confused with the trillo or "Monteverdi trill"

Some electric guitars use a (misnamed) lever called a "tremolo arm" or "whammy bar" that allows a performer to lower or (usually, to some extent) raise the pitch of a note or chord, an effect properly termed vibrato or "pitch bend". This non-standard use of the term "tremolo" refers to pitch rather than amplitude. However, the term "trem" or "tremolo" is still used to refer to a bridge system built for a whammy bar, or the bar itself. True tremolo for an electric guitar, electronic organ, or any electronic signal would normally be produced by a simple amplitude modulation electronic circuit. Electronic tremolo effects were available on many early guitar amplifiers. Tremolo effects pedals are also widely used to achieve this effect. In acoustic instruments, for e.g. guitar, tremolo effect provides the sustenance of sound for a longer span.[1]

History[]

Although it had already been employed as early as 1617 by Biagio Marini and again in 1621 by Giovanni Battista Riccio,[2] the bowed tremolo was invented in 1624 by the early 17th-century composer Claudio Monteverdi,[3][4] and, written as repeated semiquavers (sixteenth notes), used for the stile concitato effects in Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. The measured tremolo, presumably played with rhythmic regularity, was invented to add dramatic intensity to string accompaniment and contrast with regular tenuto strokes.[4] However, it was not till the time of Gluck that the real tremolo[clarification needed] became an accepted method of tone production.[5] Four other types of historical tremolos include the obsolete undulating tremolo, the bowed tremolo, the fingered tremolo (or slurred tremolo), and the bowed-and-fingered tremolo.[6]

The undulating tremolo was produced through the fingers of the right hand alternately exerting and relaxing pressure upon the bow to create a "very uncertain–undulating effect ... But it must be said that, unless violinists have wholly lost the art of this particular stroke, the result is disappointing and futile in the extreme," though it has been suggested that rather than as a legato stroke it was done as a series of jetés.[4]

There is some speculation[7] that tremolo was employed in medieval Welsh harp music, as indicated in the transcription by Robert ap Huw.

Notation[]

In musical notation, tremolo is usually notated as regular repeated demisemiquavers (thirty-second notes), using strokes through the stems of the notes. Generally, there are three strokes, except on notes which already have beams or flags: quavers (eighth notes) then take two additional slashes, and semiquavers (sixteenth notes) take one.

In the case of semibreves (whole notes), which lack stems, the strokes or slashes are drawn above or below the note, where the stem would be if there were one.

Because there is ambiguity as to whether an unmeasured tremolo or regular repeated demisemiquavers (thirty-second notes) should be played, the word tremolo or the abbreviation trem., is sometimes added. In slower music when there is a real chance of confusion, additional strokes can be used.

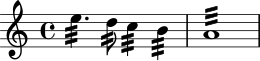

If the tremolo is between two or more notes, both notes are given the full value of the passage and the bars are drawn between them:

In some music a minim-based (half note) tremolo is drawn with the strokes connecting the two notes together as if they were beams.

Bowed string instruments[]

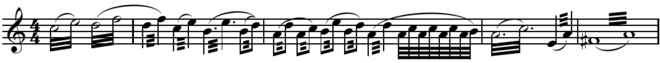

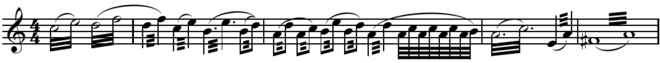

Violin fingered tremolo; notice the joining of strokes and stems is different for different time values, and that some notes shorter than eighth notes are written out, such as the last thirty-second notes on the last beat of measure three:

Fingered tremolo notation.[8]

Fingered tremolo notation.[8]

Violin bowed-and-fingered tremolo, notated the same as fingered tremolo but without slurs and with staccato above the staff:

Bowed-and-fingered tremolo notation[9]

Bowed-and-fingered tremolo notation[9]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Examples of Tremolo on Acoustic Guitar". Kapil Srivastava. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ David Fallows, "Tremolo (i)", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, ISBN 9781561592395.

- ^ Weiss and Taruskin (1984). Music in the Western World: A History in Documents, p. 146. ISBN 0-02-872900-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Forsyth 1982, p. 348.

- ^ Forsyth 1982, p. 349.

- ^ Forsyth 1982, p. 350.

- ^ Whittaker, Paul. "British Museum, Additional MS 14905; An Interpretation and Re-examination of the Music and Text" (PDF). Music of the Robert ap Huw Manuscript. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ Forsyth 1982, p. 358.

- ^ Forsyth 1982, p. 362.

Sources

- Forsyth, Cecil (1982) [1935]. Orchestration. new foreword by William Bolcom. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24383-4. OCLC 757100643.

Further reading[]

- Adler, Samuel (2016). The Study of Orchestration (4th ed.). W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-60052-0.

- Musical notation

- Musical techniques

- Italian words and phrases

- String performance techniques

- Ornamentation