Trichodysplasia spinulosa

| Trichodysplasia spinulosa | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa |

| |

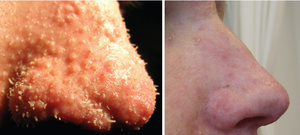

| The nose of a patient diagnosed with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Left panel shows characteristic findings of facial papules, protrusive keratotic spicules, and thickened skin; right panel shows appearance following treatment with topical cidofovir.[1] | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, dermatology |

Trichodysplasia spinulosa (also known by many other names, including viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa, viral-associated trichodysplasia, pilomatrix dysplasia and ciclosporin-induced folliculodystrophy, although the last is a misnomer) is a rare cutaneous condition that has been described almost exclusively in immunocompromised patients, usually organ transplant recipients, on regimens of immunosuppressive drugs.[2][3] As of early 2016, a total of 32 cases had been reported in the medical literature.[2] Despite its rarity, TS is believed to be underdiagnosed, and the growing population of patients on immunosuppressive drug regimens suggests its incidence may rise.[2][3] TS has been described as an emerging infectious disease.[4]

Symptoms and signs[]

The disease is characterized by flesh-colored to erythematous (reddened) papules occurring in the central region of the face and sometimes elsewhere on the body, often accompanied by protrusive "spicules" or spines made of keratin and by alopecia of affected skin, typically the eyebrows and sometimes the eyelashes or scalp hairs. Pruritus (itching) has been described in about a third of reported cases.[2] Facial papules are generally 1- to 3-mm in size.[5]: 415 The condition is considered to be benign, but can be disfiguring; the spines are often prominent, and in later stages the affected facial skin thickens noticeably.[2][3]

Causes[]

TS has been reported almost exclusively in immunocompromised patients, primarily organ transplant recipients on regimens of immunosuppressive drugs, and also in patients with hematolymphoid malignancies.[2][3] As of 2016 there were no case reports in the literature describing cases of TS in patients with HIV-AIDS.[2]

There is compelling evidence that trichodysplasia spinulosa is caused by a polyomavirus called trichodysplasia spinulosa polyomavirus (TSPyV) or Human polyomavirus 8.[2][3][1][6] There is evidence that exposure to the virus is common among healthy adults; estimates of seroprevalence (that is, prevalence of detectable antibodies against viral proteins) in immunocompetent adults range from 70 to 80% in different sample populations.[3][7][8] TSPyV infects the skin, but viral DNA is rarely detectable there in asymptomatic individuals even if they possess antibodies to the virus indicating exposure.[3] It is not known whether TS represents new primary infection or opportunistic reactivation of a latent infection.[3]

Mechanism[]

The hyperproliferation of keratinocyte inner root sheath cells in which large aggregates of viral particles can be found suggests that TSPyV actively replicates in these cells. This is thought to underlie the clinical manifestations of TS. However, the precise mechanism is not well characterized.[3] There is limited evidence implicating the large tumor antigen as responsible for inducing cellular proliferation through pathways involving phosphorylated retinoblastoma protein (pRB).[9]

Diagnosis[]

TS can be diagnosed based on clinical observations, but is usually confirmed by histopathology of a lesional biopsy or a plucked spicule. Characteristic histological findings include enlarged and abnormally organized hair follicles and hyperproliferation of inner root sheath cells containing large eosinophilic trichohyalin granules. Antibodies against major capsid protein VP1, the major component of the viral capsid, can be used to confirm the presence of viral particles in cell nuclei. Electron microscopy can also be used to detect viral particles. Quantification of viral load can be performed using quantitative PCR, as affected skin demonstrates much higher viral loads compared to unaffected skin or to asymptomatic individuals who test positive for viral DNA.[2][3]

Differential diagnosis includes other visually similar conditions affecting the hair follicles, many of which appear as drug side effects.[2] A proposed classification system lists TS as one of a group of cutaneous conditions with similar manifestations and distinct etiologies, collectively called the digitate keratoses.[10] Although confirmed TS is rare, the condition is thought to be underdiagnosed.[2]

Treatment[]

There have been too few cases of TS reported for a standard treatment to be established. In some cases, improvement in immune function has been noted to produce spontaneous improvement in TS symptoms. This pattern is consistent with the behavior of other viral diseases found in immunocompromised patients, most relevantly with the nephropathy associated in kidney transplant recipients with the polyomavirus BK virus. Antiviral drugs such as valganciclovir and cidofovir have shown benefit in treating this disorder in case reports.[2][3][11][12]

Outcomes[]

TS is considered to be a benign dysplasia, although it can be disfiguring and is sometimes itchy. It is not known whether TS lesions have the potential to develop into cancer; while this outcome has never been reported, some polyomaviruses are oncogenic. The natural history of untreated TS is not known and no long-term studies of its progress have been performed. Improvement in immune function has been reported to resolve symptoms in some individual cases. Treatment with antiviral drugs has also been reported to improve symptoms, but only as long as treatment continues.[2][3]

History[]

TS was first described in a 1995 case report as "ciclosporin-induced folliculodystrophy", thought at the time to be an adverse effect of ciclosporin treatment.[3][13] A subsequent report in 1999, which introduced the term "trichodysplasia spinulosa", used electron microscopy to identify the presence of virus particles in affected cells consistent with what were at the time known as papovaviruses.[14] (The group has since been divided into the papillomavirus and polyomavirus families.) In 2010, researchers used rolling circle amplification to recover viral DNA from TS lesions and thus discovered a novel polyomavirus, trichodysplasia spinulosa polyomavirus (TSPyV). There is compelling evidence that TSPyV is the direct causative agent of TS.[2][3]

References[]

- ^ a b van der Meijden E, Janssens RW, Lauber C, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Gorbalenya AE, Feltkamp MC (July 2010). "Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromized patient". PLOS Pathog. 6 (7): e1001024. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001024. PMC 2912394. PMID 20686659.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wu, J.H.; Nguyen, H.P.; Rady, P.L.; Tyring, S.K. (March 2016). "Molecular insight into the viral biology and clinical features of trichodysplasia spinulosa". British Journal of Dermatology. 174 (3): 490–498. doi:10.1111/bjd.14239. PMID 26479880. S2CID 26367357.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kazem, Siamaque; van der Meijden, Els; Feltkamp, Mariet C. W. (August 2013). "The trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus: virological background and clinical implications". APMIS. 121 (8): 770–782. doi:10.1111/apm.12092. PMID 23593936. S2CID 13734654.

- ^ Nawas, Zeena Y.; Tong, Yun; Kollipara, Ramya; Peranteau, Andrew J.; Woc-Colburn, Laila; Yan, Albert C.; Lupi, Omar; Tyring, Stephen K. (July 2016). "Emerging infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 75 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.033. PMID 27317512.

- ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ^ Kazem, Siamaque; van der Meijden, Els; Kooijman, Sander; Rosenberg, Arlene S.; Hughey, Lauren C.; Browning, John C.; Sadler, Genevieve; Busam, Klaus; Pope, Elena; Benoit, Taylor; Fleckman, Philip; de Vries, Esther; Eekhof, Just A.; Feltkamp, Mariet C.W. (March 2012). "Trichodysplasia spinulosa is characterized by active polyomavirus infection". Journal of Clinical Virology. 53 (3): 225–230. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2011.11.007. PMID 22196870.

- ^ van der Meijden, E; Kazem, S; Burgers, MM; Janssens, R; Bouwes Bavinck, JN; de Melker, H; Feltkamp, MC (August 2011). "Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (8): 1355–63. doi:10.3201/eid1708.110114. PMC 3381547. PMID 21801610.

- ^ Gossai, A; Waterboer, T; Nelson, HH; Michel, A; Willhauck-Fleckenstein, M; Farzan, SF; Hoen, AG; Christensen, BC; Kelsey, KT; Marsit, CJ; Pawlita, M; Karagas, MR (1 January 2016). "Seroepidemiology of Human Polyomaviruses in a US Population". American Journal of Epidemiology. 183 (1): 61–9. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv155. PMC 5006224. PMID 26667254.

- ^ a b Kazem, Siamaque; van der Meijden, Els; Wang, Richard C.; Rosenberg, Arlene S.; Pope, Elena; Benoit, Taylor; Fleckman, Philip; Feltkamp, Mariet C. W.; Deb, Sumitra (7 October 2014). "Polyomavirus-Associated Trichodysplasia Spinulosa Involves Hyperproliferation, pRB Phosphorylation and Upregulation of p16 and p21". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e108947. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j8947K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108947. PMC 4188587. PMID 25291363.

- ^ Caccetta, Tony Philip; Dessauvagie, Ben; McCallum, Dugald; Kumarasinghe, Sujith Prasad (July 2012). "Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis: A proposed algorithm for the digitate keratoses". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 67 (1): e49–e55. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.023. PMID 21050621.

- ^ Holzer, Aton M.; Hughey, Lauren C. (January 2009). "Trichodysplasia of immunosuppression treated with oral valganciclovir". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 60 (1): 169–172. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.051. PMC 2708076. PMID 19103376.

- ^ Wanat, Karolyn A. (1 February 2012). "Viral-Associated Trichodysplasia". Archives of Dermatology. 148 (2): 219–23. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.1413. PMC 3346264. PMID 22351821.

- ^ Izakovic, J; Büchner, SA; Düggelin, M; Guggenheim, R; Itin, PH (December 1995). "[Hair-like hyperkeratoses in patients with kidney transplants. A new cyclosporin side-effect]". Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift für Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 46 (12): 841–6. doi:10.1007/s001050050350. PMID 8567267. S2CID 6750161.

- ^ Haycox, CL; Kim, S; Fleckman, P; Smith, LT; Piepkorn, M; Sundberg, JP; Howell, DN; Miller, SE (December 1999). "Trichodysplasia spinulosa--a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. Symposium Proceedings. 4 (3): 268–71. doi:10.1038/sj.jidsp.5640227. PMID 10674379.

External links[]

- Virus-related cutaneous conditions

- Rare diseases

- Rare infectious diseases