Trimetazidine

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (February 2022) |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | completely absorbed at around 5 hours, steady state is reached by 60th hour |

| Protein binding | low (16%) |

| Metabolism | minimal |

| Elimination half-life | 7 to 12 hours |

| Excretion | mainly renal (unchanged), exposure is increased in renal impairment – on average by four-fold in subjects with severe renal impairment (CrCl <30 ml/min) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.023.355 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H22N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 266.341 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

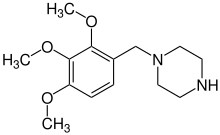

Trimetazidine (IUPAC: 1-(2,3,4-trimethoxybenzyl)piperazine) is a drug for angina pectoris sold under many brand names.[1] Trimetazidine is described as the first cytoprotective anti-ischemic agent developed and marketed by Laboratoires Servier (France). It is an anti-ischemic (antianginal) metabolic agent of the fatty acid oxidation inhibitor class, meaning that it improves myocardial glucose utilization through inhibition of fatty acid metabolism.

Medical uses[]

Trimetazidine is usually prescribed as a long-term treatment of angina pectoris, and in some countries (including France) for tinnitus and dizziness. It is taken twice a day. In 2012, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) finished a review of benefits and risks of trimetazidine and recommended restricting use of trimetazidine-containing medicines to just as an additional treatment of angina pectoris in cases of inadequate control by or intolerance to first-line antianginal therapies.[2]

Controlled studies in angina patients have shown that trimetazidine increases coronary flow reserve, thereby delaying the onset of ischemia associated with exercise, limits rapid swings in blood pressure without any significant variations in heart rate, significantly decreases the frequency of angina attacks, and leads to a significant decrease in the use of nitrates.

However, there was a 2020 placebo-controlled, randomized trial assessed trimetazidine in over 6000 patients who had recently had a coronary intervention. Trimetazidine was administered along with typical anti-anginal therapy versus typical anti-anginal therapy alone and no significant difference between the two groups with respect to cardiac death, hospital admission for a cardiac event, recurrence or persistence of angina, or the need for repeat coronary angiography was found.[3] This study therefore calls into question the clinical utility of trimetazidine in the treatment of angina.

It improves left ventricular function in diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Recently, it has been shown to be effective in patients with heart failure of different etiologies.[4][5]

Use as a performance-enhancing drug[]

Although trimetazidine was already developed for medical use in the 1970s, it only became listed in the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) prohibited substances list under the category of "hormone and metabolic modulators" beginning in 2014,[6][7] and its use is prohibited at all times "in- and out-of-competition."[8]

In 2014, Chinese Olympic champion swimmer Sun Yang tested positive for trimetazidine, which had been newly banned four months earlier and classified as a prohibited stimulant by WADA; Sun Yang and his doctor were not made aware of the changes to the use of the drug of which he was prescribed, and was consequently banned by the Chinese Swimming Association for three months.[9]

In January 2015, WADA reclassified and downgraded trimetazidine from a "stimulant" to a "modulator of cardiac metabolism."[10][11]

In 2018, U.S. swimmer Madisyn Cox was banned from competition for six months after a urine sample tested positive for trimetazidine. FINA initially reduced her suspension from four years to two years because of Cox's testimony that she did not knowingly ingest the drug.[12] Upon analysis of both opened and sealed bottles of Cooper Complete Elite Athletic multivitamins, the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) determined that the multivitamins were the source, and reduced Cox's suspension to six months. The suspension expired on September 3, 2018.[13]

In February 2022, the medal ceremony for the figure skating team event at the 2022 Olympics originally scheduled for Tuesday, 8 February, was delayed over what International Olympic Committee (IOC) spokesperson Mark Adams described as a situation that required "legal consultation" with the International Skating Union (ISU).[14] Several media outlets reported on Wednesday that the issue was over a December 2021 test for trimetazidine by the Russian Olympic Committee's Kamila Valieva,[15][16] whose result was released on February 11. The results are pending investigation.[17] Valieva was cleared by the Russian Anti-Doping Agency (RUSADA) on February 9, a day after positive results of a test held in December 2021 were released. The IOC, WADA, and ISU are appealing RUSADA's decision.[18] On February 14, the Court of Arbitration for Sport ruled that Valieva would be allowed to compete in the women's single event, deciding that preventing her from competing "would cause her irreparable harm in the circumstances", though her gold medal in the team event was still under consideration. The favorable decision from the court was made in part due to her age, as minor athletes are subject to different rules than adult athletes.[19][20]

The IOC announced that the medal ceremony would not take place until the investigation is over and there is a concrete decision whether to strip Russia of their medals.[21]

Popular Science published an overview of scientific research about the potential for the use of trimetazidine as a performance enhancing drug for athletes. The author of the article concluded in its headline that "there's no hard proof that it would improve a figure skater's performance". Scott Powers, a physiologist at the University of Florida who studies the effects of exercise on the heart explained how trimetazidine was included in WADA list. "I've been involved in roundtables with the International Olympic Committee, and I think their policy is: When in doubt, ban the drug," says Scott Powers. "I guess they're just trying to err on the possibility that this drug may be an ergogenic aid."[22] Doping expert Klaas Faber referred to "grossly inconsistent anti-doping rules" in Sun Yang's case. Faber has pointed out for years the necessity to establish thresholds for trimetazidine detected so as to avoid any inadvertent positive doping cases. Faber has detailed some of these observations published in the journal Science & Justice.[23][24]

On the efficacy of the drug on figure skating and Valieva in particular, heart expert Benjamin J. Levine, a professor of exercise science at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, said "The chance that trimetazidine would improve her performance, in my opinion, is zero. The heart has plenty of blood. And the heart is so good at using different fuels."[22][25]

Aaron Baggish, director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital said "In theory, trimetazidine could aid endurance athletes who have to generate high cardiac output, such as cyclists, rowers and long-distance runners, but would be unlikely to have a direct impact on a figure skater's performance, where there is less demand on the heart."[26]

Adverse effects[]

Trimetazidine has been treated as a drug with a high safety and tolerability profile.[27]

Information is scarce about trimetazidine's effect on mortality, cardiovascular events, or quality of life. Long-term, randomized, controlled trials comparing trimetazidine against standard antianginal agents, using clinically important outcomes would be justifiable.[27] Recently, an international multicentre retrospective cohort study has indeed shown that in patients with heart failure of different etiologies, the addition of trimetazidine on conventional optimal therapy can improve mortality and morbidity.[28]

The EMA recommends that doctors should no longer prescribe trimetazidine for the treatment of patients with tinnitus, vertigo, or disturbances in vision.[2] The recent EMA evaluation also revealed rare cases (3.6/1 000 000 patient years) of parkinsonian (or extrapyramidal) symptoms (such as tremor, rigidity, akinesia, hypertonia), gait instability, restless leg syndrome, and other related movement disorders; most patients recovered within 4 months after treatment discontinuation, so doctors are advised not to prescribe the medicine either to patients with Parkinson disease, parkinsonian symptoms, tremors, restless leg syndrome, or other related movement disorders, or to patients with severe renal impairment.[2]

Mechanism of action[]

Trimetazidine inhibits beta-oxidation of fatty acids by blocking long-chain 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, which enhances glucose oxidation.[29] In an ischaemic cell, energy obtained during glucose oxidation requires less oxygen consumption than in the beta-oxidation process. Potentiation of glucose oxidation optimizes cellular energy processes, thereby maintaining proper energy metabolism during ischaemia. By preserving energy metabolism in cells exposed to hypoxia or ischaemia, trimetazidine prevents a decrease in intracellular ATP levels, thereby ensuring the proper functioning of ionic pumps and transmembrane sodium-potassium flow whilst maintaining cellular homeostasis.[30]

References[]

- ^ "Trimetazidine". Drugs.com.

- ^ a b c "European Medicines Agency recommends restricting use of trimetazidine-containing medicines" (PDF). Press release. European Medicines Agency. 2012-06-12.

- ^ Lancet. 2020;396(10254):830. Epub 2020 Aug 30. Efficacy and safety of trimetazidine after percutaneous coronary intervention (ATPCI): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ferrari R, Ford I, Fox K, Challeton JP, Correges A, Tendera M, WidimskýP, Danchin N, ATPCI investigators.

- ^ Fragasso G, Palloshi A, Puccetti P, Silipigni C, Rossodivita A, Pala M, Calori G, Alfieri O, Margonato A (September 2006). "A randomized clinical trial of trimetazidine, a partial free fatty acid oxidation inhibitor, in patients with heart failure". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48 (5): 992–998. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.060. PMID 16949492.

- ^ Tuunanen H, Engblom E, Naum A, Någren K, Scheinin M, Hesse B, Juhani Airaksinen KE, Nuutila P, Iozzo P, Ukkonen H, Opie LH, Knuuti J (September 2008). "Trimetazidine, a metabolic modulator, has cardiac and extracardiac benefits in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy". Circulation. 118 (12): 1250–1258. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.778019. PMID 18765391.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Ramsay, George (10 February 2022). "Trimetazidine: Drug banned by WADA makes 'your heart work more efficiently'". CNN. CNN. CNN. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ Howes, Laura (17 February 2022). "What is trimetazidine and why is it banned in Olympic competition?". cen.acs.org. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

Trimetazidine (TMZ) is the generic name for the chemical that acts as a vasodilator and was discovered over 50 years ago (1970s). TMZ is commonly prescribed in Europe and Russia where it is taken as a pill or in delayed-release tablets to treat angina as well as vertigo, tinnitus, and certain visual disturbances. Since 2014, WADA has classed TMZ as a prohibited substance.

- ^ "World Anti-Doping Code International Standard Prohibited List" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency. 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Chinese swimmer Sun Yang is being falsely punished". Sports Integrity Initiative. 2020-03-19. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- ^ "Sun Yang, el chico malo de la natación que gana todo pero al que nadie quiere". yahoo.es. 22 July 2019.

- ^ "The Sun Yang Doping Case: Chapter Two of an Olympic Champion". 2 December 2014.

- ^ "FINA reduces doping ban for world champ Madisyn Cox". CBC. 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ^ Gibbs, Robert (2018-08-31). "Madisyn Cox's Suspension Reduced to Six Months after Trimetazidine Detected in Multivitamin". SwimSwam. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ^ "Olympic medals in team figure skating delayed by legal issue". AP News. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Tétrault-Farber, Gabrielle; Axon, Iain; Grohmann, Karolos (9 February 2022). "Figure skating-Russian media say teen star tested positive for banned drug". Reuters. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Brennan, Christine (9 February 2022). "Positive drug test by Russian Kamila Valieva has forced a delay of Olympic team medals ceremony". USA Today.

- ^ "Valieva failed drugs test confirmed". BBC Sport. February 11, 2022.

- ^ "Russian anti-doping agency allowed Kamila Valieva to compete in Olympics despite failed drug test". CNN.

- ^ "Russian skater Kamila Valieva cleared to compete at Olympics". AP NEWS. 2022-02-14. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

- ^ "CAS Ad Hoc Media Release" (PDF).

- ^ IOC EB decides no medal ceremonies following CAS decision on the case of ROC skater

- ^ a b "Kamila Valieva's 'doping' drug probably doesn't give athletes an edge". February 16, 2022.

- ^ Burke, Michael G.; Faber, Klaas (September 21, 2012). "A plea for thresholds, i.e., maximal allowed levels for prohibited substances, to prevent questionable doping convictions". Science & Justice: Journal of the Forensic Science Society. 52 (3): 199–201. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2012.02.002. PMID 22841145 – via PubMed.

- ^ "The Sun Yang Doping Case: Chapter Two Of An Olympic Champion". December 2, 2014.

- ^ "What Is Trimetazidine, and Would It Have Helped Kamila Valieva of Russia?". The New York Times.

- ^ "What to know about Trimetazidine, the drug at the center of the Olympic doping case". Washington Post. 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

- ^ a b Ciapponi A, Pizarro R, Harrison J (2017). Ciapponi A (ed.). "Trimetazidine for stable angina". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (3): CD003614. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003614.pub3. PMC 6464521. PMID 16235330. (Retracted)|This review series was withdrawn because the authors did not opt to continue updating it; the journal has not "withdrawn" it in the usual sense

- ^ Fragasso G, Rosano G, Baek Hong S, Sisakian H, Di Napoli P, Alberti L, Calori G, Kang SM, Sahakyan A, Vitale C, Marazzi G, Margonato A, Belardinelli R. "Effect of partial acid oxidation inhibition with trimetazidine on mortality and morbidity in heart failure: results from an international multicentre retrospective cohort study." Int J Cardiol. 2013; 163: 320–325.

- ^ Kantor PF, Lucien A, Kozak R, Lopaschuk GD (March 2000). "The antianginal drug trimetazidine shifts cardiac energy metabolism from fatty acid oxidation to glucose oxidation by inhibiting mitochondrial long-chain 3-ketoacyl coenzyme A thiolase". Circ. Res. 86 (5): 580–588. doi:10.1161/01.RES.86.5.580. PMID 10720420.

- ^ Stanley WC, Marzilli M (April 2003). "Metabolic therapy in the treatment of ischaemic heart disease: the pharmacology of trimetazidine". Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 17 (2): 133–145. doi:10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00154.x. PMID 12667223. S2CID 10407498.

Further reading[]

- Sellier P, Broustet JP (2003). "Assessment of anti-ischemic and antianginal effect at trough plasma concentration and safety of trimetazidine MR 35 mg in patients with stable angina pectoris: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 3 (5): 361–369. doi:10.2165/00129784-200303050-00007. PMID 14728070. S2CID 68895472.

- Génissel P, Chodjania Y, Demolis JL, Ragueneau I, Jaillon P (2004). "Assessment of the sustained release properties of a new oral formulation of trimetazidine in pigs and dogs and confirmation in healthy human volunteers". Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 29 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1007/BF03190575. PMID 15151172. S2CID 10455129.

- Antianginals

- Piperazines

- Phenol ethers

- Laboratoires Servier

- World Anti-Doping Agency prohibited substances