Tupac Shakur

Tupac Shakur | |

|---|---|

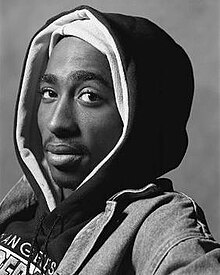

Shakur in 1991 | |

| Born | Lesane Parish Crooks June 16, 1971 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | September 13, 1996 (aged 25) Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Drive-by homicide (gunshot wounds) |

| Resting place | Cremated, ashes given to family |

| Other names |

|

| Education | Tamalpais High School |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1987–1996[1][2] |

| Spouse(s) | Keisha Morris

(m. 1995; div. 1996) |

| Partner(s) |

|

| Parent(s) | Afeni Shakur Billy Garland |

| Relatives | Mutulu Shakur (step-father) Assata Shakur (step-aunt) Mopreme Shakur (step-brother) Kastro (cousin) |

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Marin County, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Labels |

|

| Associated acts |

|

| Website | www |

| Signature | |

| |

Tupac Amaru Shakur (/ˈtuːpɑːk ʃəˈkʊər/ TOO-pahk shə-KOOR; born Lesane Parish Crooks, June 16, 1971 – September 13, 1996), better known by his stage name 2Pac and by his alias Makaveli, was an American rapper, songwriter, and actor. He is widely considered to be one of the most influential rappers of all time. Much of Shakur's work has been noted for addressing contemporary social issues that plagued inner cities, and he has often been considered a symbol of activism against inequality.

Shakur was born in Manhattan, a borough of New York City, but relocated to Baltimore, Maryland in 1984 and then the San Francisco Bay Area in 1988. He moved to Los Angeles in 1993 to further pursue his music career. By the time he released his debut album 2Pacalypse Now in 1991, he had become a central figure in West Coast hip hop, introducing social issues to the genre at a time when gangsta rap was dominant in the mainstream.[3][4] Shakur achieved further critical and commercial success with his follow-up albums Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z... (1993) and Me Against the World (1995).[5]

In 1995, Shakur served eight months in prison on sexual assault charges, but was released after agreeing to sign with Marion "Suge" Knight's label Death Row Records in exchange for Knight posting his bail. Following his release, Shakur became heavily involved in the growing East Coast–West Coast hip hop rivalry.[6] His double-disc album All Eyez on Me (1996), abandoning introspective lyrics for volatile gangsta rap,[7] was certified Diamond by the RIAA. On September 7, 1996, Shakur was shot four times by an unknown assailant in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada; he died six days later and the gunman was never captured. Shakur's friend-turned-rival, the Notorious B.I.G., was at first considered a suspect due to the pair's public feud, but was also murdered in another drive-by shooting six months later in Los Angeles, California.[8][9] Five more albums have been released since Shakur's death, all of which have been certified Platinum in the United States.

Shakur is one of the best-selling music artists of all time, having sold over 75 million records worldwide. In 2002, he was inducted into the Hip-Hop Hall of Fame.[10] In 2017, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.[11] Rolling Stone named Shakur in its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[12] Outside music, Shakur also found considerable success as an actor, with his starring roles as Bishop in Juice (1992), Lucky in Poetic Justice (1993) where he starred alongside Janet Jackson, Ezekiel in Gridlock'd (1997), and Jake in Gang Related (1997), all of which garnered praise from critics.

Personal life

Shakur was born on June 16, 1971, in the East Harlem section of Manhattan in New York City.[13] While born Lesane Parish Crooks,[14][15][16] he was renamed, at age one, after Túpac Amaru II[17] (the descendant of the last Incan ruler, Túpac Amaru), who was executed in Peru in 1781 after his failed revolt against Spanish rule.[18] Shakur's mother explained, "I wanted him to have the name of revolutionary, indigenous people in the world. I wanted him to know he was part of a world culture and not just from a neighborhood."[17]

Shakur had an older stepbrother, Mopreme "Komani" Shakur, and a half-sister, Sekyiwa, two years his junior.[19] His parents, Afeni Shakur—born Alice Faye Williams in North Carolina—and his birth father, Billy Garland, had been active Black Panther Party members in New York in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[20]

Panther heritage

A month before Shakur's birth, his mother Afeni was tried in New York City as part of the Panther 21 criminal trial. She was acquitted of over 150 charges.[21][22]

Other family members who were involved in the Black Panthers' Black Liberation Army were convicted of serious crimes and imprisoned, including Shakur's stepfather, Mutulu Shakur, who spent four years among the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives. Mutulu Shakur was apprehended in 1986 and subsequently convicted for a 1981 robbery of a Brinks armored truck, during which police officers and a guard were killed.[23]

Shakur's godfather, Elmer "Geronimo" Pratt, a high-ranking Black Panther, was convicted of murdering a school teacher during a 1968 robbery. His sentence was overturned when it was revealed that the prosecution had hidden evidence that he was in a meeting 400 mi (640 km) away at the time of the murders.[24][25]

School years

In 1984, Shakur's family moved from New York City to Baltimore, Maryland.[26] He attended eighth grade at Roland Park Middle School, then two years at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. On transfer to the Baltimore School for the Arts, he studied acting, poetry, jazz, and ballet.[27][28] He performed in Shakespeare's plays—depicting timeless themes, now seen in gang warfare, he would recall[29]—and as the Mouse King role in The Nutcracker ballet.[23] With his friend Dana "Mouse" Smith as beatbox, he won competitions as reputedly the school's best rapper.[30] Also known for his humor, he could mix with all crowds.[31] As a teen, he listened to musicians including Kate Bush, Culture Club, Sinéad O'Connor, and U2.[32]

At Baltimore's arts high school, Shakur befriended Jada Pinkett, who would become a subject of some of his poems.[33] After his death, she would call him "one of my best friends. He was like a brother. It was beyond friendship for us. The type of relationship we had, you only get that once in a lifetime."[34][35] Upon connecting with the Baltimore Young Communist League USA,[36][37][38] Shakur dated the daughter of the director of the local chapter of the Communist Party USA.[39] In 1988, Shakur moved to Marin City, California, a small, impoverished community,[40] about 5 miles (8.0 km) north of San Francisco.[41] In nearby Mill Valley, he attended Tamalpais High School,[42] where he performed in several theater productions.[43]

Later relations

In Shakur's adulthood he continued befriending individuals of diverse backgrounds. His friends would range from Mike Tyson[44] and Chuck D[45] to Jim Carrey[46] and Alanis Morissette, who in April 1996 said that she and Shakur were planning to open a restaurant together.[47][48]

Shakur briefly dated Madonna in 1994.[49][50] On April 29, 1995, Shakur married his then girlfriend Keisha Morris, a pre-law student.[51][52] The marriage was annulled ten months later.[53] In a 1993 interview published in The Source, Shakur berated record producer Quincy Jones for his interracial marriage to actress Peggy Lipton.[54] Their daughter Rashida Jones responded with an irate open letter.[55] Years later, Shakur apologized to her sister Kidada Jones, who he was dating at the time of his death in 1996.[56]

Music career

In January 1991, Shakur debuted under the stage name 2Pac on rap group Digital Underground's single "Same Song". The song was featured on the soundtrack of the 1991 film Nothing but Trouble. His first two solo albums, 2Pacalypse Now (1991) and Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z... (1993), preceded Thug Life: Volume 1 (1994), the only album with his side group Thug Life.[57] Rapper/producer Stretch guests on the three albums.

Shakur's third solo album, Me Against the World (1995), features rap clique Dramacydal, reshaping as Outlawz on Shakur's fourth solo album, and last in his lifetime, All Eyez on Me (1996). At the time of his death, another solo album was already finished. The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory (1996), under the stage name Makaveli, was recorded in one week in August 1996, whereas later posthumous albums are archival productions. Later posthumous albums are R U Still Down? (1997), Greatest Hits (1998), Still I Rise (1999), Until the End of Time (2001), Better Dayz (2002), Loyal to the Game (2004), Pac's Life (2006).[58]

Beginnings: 1989–1991

Shakur began recording using the stage name MC New York in 1989. That year, he began attending the poetry classes of Leila Steinberg, and she soon became his manager.[59][40] Steinberg organized a concert for Shakur and his rap group Strictly Dope. Steinberg managed to get Shakur signed by Atron Gregory, manager of the rap group Digital Underground.[40] In 1990, Gregory placed him with the Underground as a roadie and backup dancer.[40][60] Under the stage name 2Pac, he debuted on the group's January 1991 single "Same Song", leading the group's January 1991 EP titled This Is an EP Release,[40] while Shakur appeared in the music video. It also went on the soundtrack of the February 1991 movie Nothing but Trouble, starring Dan Aykroyd, John Candy, Chevy Chase, and Demi Moore.[40]

Rising star: 1992–1993

Shakur's debut album, 2Pacalypse Now—alluding to the 1979 film Apocalypse Now—arriving in November 1991, would bear three singles. Some prominent rappers—like Nas, Eminem, Game, and Talib Kweli—cite it as an inspiration.[61] Aside from "If My Homie Calls", the singles "Trapped" and "Brenda's Got a Baby" poetically depict individual struggles under socioeconomic disadvantage.[62]

US Vice President Dan Quayle partially reacted, "There's no reason for a record like this to be released. It has no place in our society." Tupac, finding himself misunderstood,[29] explained, in part, "I just wanted to rap about things that affected young Black males. When I said that, I didn't know that I was gonna tie myself down to just take all the blunts and hits for all the young Black males, to be the media's kicking post for young Black males."[63][64] In any case, 2Pacalypse Now was certified Gold, half a million copies sold. The album addresses urban Black concerns said to remain relevant to the present day.[40]

Shakur's second album, Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z..., arrived in February 1993. A critical and commercial advance, it debuted at No. 24 on the pop albums chart, the Billboard 200.[65] An overall more hardcore album, it emphasizes Tupac's sociopolitical views, and has a metallic production quality. It features Ice Cube, the famed primary creator of N.W.A's "Fuck tha Police", who, in his own solo albums, had newly gone militantly political, along with L.A.'s original gangsta rapper, Ice-T, who in June 1992 had sparked controversy with his band Body Count's track "Cop Killer".

In fact, in its vinyl release, side A, tracks 1 to 8, is labeled the "Black Side", while side B, tracks 9 to 16, is the "Dark Side". Nonetheless, the album carries the single "I Get Around", a party anthem featuring Digital Underground's Shock G and Money-B, which would render Shakur's popular breakthrough, reaching No. 11 on the pop singles chart, the Billboard Hot 100. And it carries the optimistic compassion of another hit, "Keep Ya Head Up", an anthem for women empowerment. This album would be , with a million copies sold. As of 2004, among Shakur albums, including of posthumous and compilation albums, the Strictly album would be 10th in sales, about 1,366,000 copies.[66]

Stardom: 1994–1995

In late 1993, Shakur formed the group Thug Life with Tyrus "Big Syke" Himes, Diron "Macadoshis" Rivers, his stepbrother Mopreme Shakur, and Walter "Rated R" Burns. Thug Life released its only album, Thug Life: Volume 1, on October 11, 1994, which is certified Gold. It carries the single "Pour Out a Little Liquor", produced by Johnny "J" Jackson, who would also produce much of Shakur's album All Eyez on Me. Usually, Thug Life performed live without Tupac.[67] The track also appears on the 1994 film Above the Rim's soundtrack. But due to gangsta rap being under heavy criticism at the time, the album's original version was scrapped, and the album redone with mostly new tracks. Still, along with Stretch, Tupac would perform the first planned single, "Out on Bail", which was never released, at the 1994 Source Awards.[68]

Shakur's third album, arriving in March 1995 as Me Against the World, is now hailed as his magnum opus, and commonly ranks among the greatest, most influential rap albums. The album sold 240,000 copies in its first week, setting a then record for highest first-week sales for a solo male rapper.[69] The lead single, "Dear Mama", arrived in February with the B side "Old School".[70] The album's most successful single, it topping the Hot Rap Singles chart, and peaked at No. 9 on the pop singles chart, the Billboard Hot 100.[7] In July, it was certified Platinum.[71] It ranked No. 51 on the year-end charts. The second single, "So Many Tears", released in June,[72] reached No. 6 on the Hot Rap Singles chart and No. 44 on Hot 100.[7] August brought the final single, "Temptations",[73] reaching No. 68 on the Hot 100, No. 35 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles & Tracks, and No. 13 on the Hot Rap Singles.[7] At the 1996 Soul Train Music Awards, Shakur won for best rap album.[74] In 2001, it ranked 4th among his total albums in sales, with about 3 million copies sold in the US.[75]

Superstardom: 1995–1996

While imprisoned February to October 1995, Shakur wrote only one song, he would say.[76] Rather, he took to political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli's treatise The Prince and military strategist Sun Tzu's treatise The Art of War.[77] And on Shakur's behalf, his wife Keisha Morris communicated to Suge Knight of Death Row Records that Shakur, in dire straits financially, needed help, his mother about to lose her house.[78] In August, after sending $15,000 for her, Suge began visiting Shakur in prison.[78] In one of his letters to Nina Bhadreshwar, recently hired to edit a planned magazine, Death Row Uncut,[79] Shakur discusses plans to start a "new chapter".[80] Eventually, music journalist Kevin Powell would say that Shakur, once released, became more aggressive, and "seemed like a completely transformed person".[81]

Shakur's fourth album, All Eyez on Me, arrived on February 13, 1996. Of two discs, it basically was rap's first double album—meeting two of the three albums due in Shakur's contract with Death Row—and bore five singles while perhaps marking the peak of 1990s rap.[82] The album shows Shakur rapping about the gangsta lifestyle, leaving behind his previous political messages. With standout production, the album has more party tracks and often a triumphant tone.[7] As Shakur's second album to hit No. 1 on both the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart and the pop albums chart, the Billboard 200,[7] it sold 566,000 copies in its first week and was it was certified 5× Multi-Platinum in April.[83] "How Do U Want It" as well as "California Love" reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. At the 1997 Soul Train Awards, it won in R&B/Soul or Rap Album of the Year.[84] At the 24th American Music Awards, Shakur won Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Artist.[85] The album was certified 9× Multi-Platinum in June 1998,[86] and 10× in July 2014.[87]

Shakur's fifth and final studio album, The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory, commonly called simply The 7 Day Theory, was released under a newer stage name, Makaveli.[88] The album had been created in seven days total during August 1996.[89] The lyrics were written and recorded in three days, and mixing took another four days. In 2005, MTV.com ranked The 7 Day Theory at No. 9 among hip hop's greatest albums ever,[90] and by 2006 a classic album.[91] Its singular poignance, through hurt and rage, contemplation and vendetta, resonate with many fans.[92] But according to George "Papa G" Pryce, Death Row Records' then director of public relations, the album was meant to be "underground", and "was not really to come out", but, "after Tupac was murdered, it did come out."[93] It peaked at No. 1 on Billboard's Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart and on the Billboard 200,[94] with the second-highest debut-week sales total of any album that year.[95] On June 15, 1999, it was certified 4× Multi-Platinum.[96]

Film career

Shakur's first film appearance was in the 1991 film Nothing but Trouble, a cameo by the Digital Underground. In 1992, he starred in Juice, where he plays the fictional Roland Bishop, a militant and haunting individual. Rolling Stone's Peter Travers calls him "the film's most magnetic figure".[97]

Then, in 1993, Shakur starred alongside Janet Jackson in John Singleton's romance film, Poetic Justice. Shakur then played another gangster, the fictional Birdie, in Above the Rim. Soon after Shakur's death, three more films starring him were released, Bullet (1996), Gridlock'd (1997), and Gang Related (1997).[98][99]

Director Allen Hughes had cast Shakur as Sharif in the 1993 film Menace II Society, but replaced him once Shakur assaulted him on set due to a discrepancy with the script. Nonetheless, in 2013, Hughes appraises that Shakur would have outshone the other actors "because he was bigger than the movie".[100] For the lead role in the eventual 2001 film Baby Boy, a role played by Tyrese Gibson, director John Singleton originally had Shakur in mind.[101] Ultimately, the set design includes in the protagonist's bedroom a Shakur mural, and the film's score includes the Shakur song "Hail Mary".[102]

Criminal and civil cases

1991 Oakland Police Department lawsuit

In October 1991, Shakur filed a $10 million lawsuit against the Oakland Police Department for allegedly brutalizing him over jaywalking. The case was settled for about $43,000.[103]

Shooting of Qa'id Walker-Teal

On August 22, 1992, in Marin City, Shakur performed outdoors at a festival. For about an hour after the performance, he signed autographs and posed for photos. A conflict broke out and Shakur allegedly drew a legally carried Colt Mustang but dropped it on the ground. Shakur claimed that someone with him then picked it up when it accidentally discharged. About 100 yards (90 meters) away in a schoolyard, Qa'id Walker-Teal, a boy aged 6 on his bicycle, was fatally shot in the forehead. Police matched the bullet to a .38-caliber pistol registered to Shakur. His stepbrother Maurice Harding was arrested, but no charges were filed. Lack of witnesses stymied prosecution. In 1995, Qa'id's mother filed a wrongful death suit against Shakur, which was settled for about $300,000 to $500,000.[104][105]

Shooting in Atlanta

In October 1993, in Atlanta, Mark Whitwell and Scott Whitwell, two brothers who were both off-duty police officers, were out celebrating with their wives after one of them had passed the state's bar examination. Drunk, the officers were crossing the street when a passing car carrying Shakur allegedly almost struck them. The Whitwells argued with the car's occupants. When a second car arrived, the Whitwells ran away, as Shakur shot one officer in the buttocks and the other in the leg, back, or abdomen. Shakur was charged in the shooting. Mark Whitwell was charged with firing at Shakur's car and later with making false statements to investigators. Prosecutors ultimately dropped all charges against both parties. Both brothers filed civil suits against Shakur; Mark Whitwell's was settled out of court, while Scott Whitwell's $2 million lawsuit resulted in a default judgment entered against the rapper's estate.[106][107]

Assault convictions

On April 5, 1993, charged with felonious assault, Shakur allegedly threw a microphone and swung a baseball bat at rapper Chauncey Wynn, of the group M.A.D., at a concert at Michigan State University. On September 14, 1994, Shakur pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor, and was sentenced to 30 days in jail, twenty of them suspended, and ordered to 35 hours of community service.[108][109]

Slated to star as Sharif in the 1993 Hughes Brothers' film Menace II Society, Shakur was replaced by actor Vonte Sweet after allegedly assaulting one of the film's directors, Allen Hughes. In early 1994, Shakur served 15 days in jail after being found guilty of the assault.[110][111] The prosecution's evidence included a Yo! MTV Raps interview where Shakur boasts that he had "beat up the director of Menace II Society".[112]

Sexual assault conviction

In November 1993, Shakur and three other men were charged in New York with sexually assaulting a woman in his hotel room. The woman, Ayanna Jackson, alleged that after consensual oral sex in his hotel room, she returned a later day, but then was raped by him and other men there. Interviewed on The Arsenio Hall Show, Shakur said he was hurt that "a woman would accuse me of taking something from her".[113]

On December 1, 1994, Shakur was convicted of first-degree sexual abuse, but acquitted of associated sodomy and gun charges. In February 1995, he was sentenced to 18 months to 4+1⁄2 years in prison by a judge who decried "an act of brutal violence against a helpless woman".[114][115] On October 12, 1995, pending judicial appeal, Shakur was released from Clinton Correctional Facility,[29] once Suge Knight, CEO of Death Row Records, arranged for posting of his $1.4 million bond.[103] On April 5, 1996, Shakur was sentenced to 120 days in jail for violating his release terms by failing to appear for a road cleanup job,[116] but on June 8, his sentence was deferred via appeals pending in other cases.[117]

New York scene 1990s

In 1991, Shakur debuted on a new record label, Interscope Records, that knew little about rap music. Until that year, Ruthless Records, formed during 1986 in Los Angeles county's Compton city, had prioritized rap, and its group N.W.A had led gangsta rap to Platinum sales, but N.W.A's lyrics, outrageously violent and misogynist, precluded mainstream breakthrough. On the other hand, also specializing in rap, Profile Records, in New York City, had a mainstream, pop breakthrough, Run-DMC's "Walk This Way", in 1986. In April 1991, N.W.A disbanded via Dr. Dre's departure to, with Suge Knight, launch Death Row Records, in Los Angeles city.[118] With its very first two albums, Death Row became the first record label both to prioritize rap and to regularly release mainstream, pop hits with it.[118]

Released by Death Row in late 1992, Dre's The Chronic—its "Nuthin' but a 'G' Thang" ubiquitous on pop radio and "Let Me Ride" winning a Grammy—was trailed in late 1993 by Snoop's Doggystyle.[118] Gangsta rap, no less, these albums and more propelled the West Coast, for the first time, ahead of New York to rap's center stage.[118] But meanwhile, in 1993, Andre Harrell of Uptown Records, in New York, fired his star A&R man, Sean "Puff Daddy" Combs, later "P. Diddy".[118] Puffy, while leaving behind his standout projects Jodeci and Mary J. Blige—two R&B acts—took to his own, new record label, Bad Boy Records, the promising gangsta rapper Biggie Smalls, soon also known as the Notorious B.I.G.[118] His debut album, released in late 1994 as Ready to Die, promptly returned rap's spotlight to New York.[118]

Rap world

Stretch and Live squad

In 1988, Randy "Stretch" Walker, along with his brother, dubbed Majesty, and a friend debuted with an EP as rap group and production team, Live Squad, in the Queens borough of New York City.[119] Shakur's early days with Digital Underground made his acquaintance with Stretch, who featured on a track of the Digital Underground's 1991 album Sons of the P. Becoming fast friends, Shakur and Stretch recorded and performed together often.[119] Stretch as well as Live Squad contributed tracks on Shakur's first two albums, first November 1991, then February 1993, and on Shakur's side group Thug Life's only album of September 1994.

The end of Shakur's and Stretch's friendship in late 1994 surprised the New York rap scene.[119] The next Shakur album, released in March 1995, lacks Stretch, and Shakur's album after that, released in February 1996, has lines suggesting Stretch's impending death for betrayal. No objective evidence would publicly emerge to tangibly incriminate Stretch in the gun attack on Shakur, while with Stretch and two others, at about 12:30 am on November 30, 1994. In any case, after a Live Squad production session for the second album of Queens rapper Nas, Stretch's vehicle was chased while receiving fatal gunfire at about 12:30 am on November 30, 1995.[119]

Biggie and Junior M.A.F.I.A.

During 1993 and 1994, the Biggie Smalls guest verses on several singles, often R&B, like Mary J. Blige's "What's the 411? Remix", set high expectations for his debut album. The perfectionism of Puffy, still forming his Bad Boy label, extended its recording to 18 months. In 1993, visiting Los Angeles, Biggie asked a local drug dealer for an introduction to Shakur, who then welcomed Biggie and Biggie's friends to Shakur's house and treated them to recreational activities.[78] On later visits to Los Angeles, Biggie would stay at Shakur's place.[78] And when in New York, Shakur would go to Brooklyn and hang out with Biggie and his circle.[78]

During this period, at his own live shows, Shakur would call Biggie onto stage to rap with him and Stretch.[78] Together, they recorded the songs "Runnin' from the Police" and "House of Pain". Reportedly, Biggie asked Shakur to manage him, whereupon Shakur advised him that Puffy would make him a star.[78] Yet in the meantime, Shakur's lifestyle was comparatively lavish, whereas Biggie appeared to continue wearing the same pair of boots for perhaps a year.[78] Shakur welcomed Biggie to join his side group Thug Life.[78] Biggie would instead form his own side group, the Junior M.A.F.I.A., with his Brooklyn friends Lil' Cease and Lil' Kim, on Bad Boy.

Underworld

Despite the "weird" timing of Stretch's shooting death,[119] a theory implicates gunman Ronald "Tenad" Washington both here and in the 2002 murder of Run-DMC's Jam Master Jay via, as the unverified theory speculates, Kenneth "Supreme" McGriff punishing the rap mentor for recording 50 Cent despite Supreme's prohibition after this young rapper's 1999 song "Ghetto Qu'ran" had mentioned activities of the Queens drug gang Supreme Team.[120] Supreme was a friend, rather, of Irv Gotti, cofounder of Murder Inc Records,[120] whose rapper Ja Rule would vie among New York rappers after the March 1997 shooting death of Biggie, visiting Los Angeles.

Haitian Jack

By some accounts, the role Birdie, played by Shakur in the 1994 film Above the Rim, had been modeled on a New York underworld tough, Jacques "Haitian Jack" Agnant,[121] a manager and promoter of rappers.[122] Reportedly, Shakur met him at a Queens nightclub, where, noticing him amid women and champagne, Shakur asked for an introduction.[78] Reportedly, Biggie advised Shakur to avoid him, but Shakur disregarded the warning.[78]

In November 1993, in his Manhattan hotel room, Shakur received a woman's return visit. Soon, she alleged sexual assault by him and three other men there: his road manager Charles Fuller, aged 24, one Ricardo Brown, aged 30,[123] and a "Nigel", later understood as Haitian Jack.[78] In November 1994, Jack's case was split off and closed via misdemeanor plea without incarceration.[78] In 2007, for shooting at someone, he would be deported.[124] Yet in November 1994, A. J. Benza, in the New York Daily News, reported Shakur's new disdain for Jack.[78][121]

Jimmy Henchman

Through Haitian Jack, Shakur had met James "Jimmy Henchman" Rosemond.[78] Another underworld figure formidable, Jimmy Henchman doubled as music manager.[121] Bryce Wilson's Groove Theory was an early client.[121] The Game as well as Gucci Mane were later clients.[121] In 1994, a client lesser known, and signed to Uptown Records, was rapper Little Shawn, friend of Biggie and Lil' Cease.[121] Eventually, Jack and Henchman would reportedly fall out, allegedly shooting at each other in Miami.[121] And for his major drug trafficking, Henchman would be sent to prison on a life sentence.[121] But in the early 1990s, Jack and Henchman reputedly shared interests, including a specialty of robbing and extorting music artists.[121]

Shootings

November 1994

On November 30, 1994, while in New York recording verses for a mixtape of Ron G, Shakur was repeatedly distracted by his beeper.[121] Music manager James "Jimmy Henchman" Rosemond, reportedly offered Shakur $7,000 to stop by Quad Studios, in Times Square, that night to record a verse for his client Little Shawn.[78][121] Shakur was unsure, but agreed to the session as he needed the cash to offset legal costs. He arrived with Stretch and one or two others. In the lobby, three men robbed and beat him at gunpoint; Shakur resisted and was shot.[63][125] Shakur speculated that the shooting had been a set-up.[63][125][126]

Three hours after surgery, against doctor's advice, Shakur checked out of Bellevue Hospital Center. The next day, in a Manhattan courtroom bandaged in a wheelchair, he received the jury's verdict in his ongoing criminal trial for a November 1993 sexual assault in his hotel room. Convicted of three counts of sexual assault, he was acquitted of six other charges, including sodomy and gun charges.[127]

In a 1995 interview with Vibe magazine, Shakur accused Sean Combs,[128] Jimmy Henchman,[125] and Biggie, among others, of setting up or being privy to the November 1994 robbery and shooting. Vibe alerted the names of the accused.[129] The accusations were significant to the East-West Coast rivalry in hip-hop, the accusation was because Sean Combs and Christopher Wallace were at Quad Studios at the time and in 1995, months later, Combs and Wallace releasing song "Who Shot Ya?", whereas the song made no direct reference or naming of Shakur, Shakur took it as a mockery of his shooting and thought they could be responsible, so he released a (direct) diss song called "Hit 'Em Up", where he targeted Wallace, Combs, their record label, Junior M.A.F.I.A., and at the end of "Hit 'Em Up", he mentions rivals Mobb Deep and Chino XL.[130][131][132][133][134]

In March 2008, Chuck Philips, in the Los Angeles Times, reported on the 1994 ambush and shooting.[135] The newspaper later retracted the article since it relied partially on FBI documents later discovered forged, supplied by a man convicted of fraud.[136] In June 2011, convicted murderer Dexter Isaac, incarcerated in Brookyn, issued a confession that he had been one of the gunmen who had robbed and shot Shakur at Henchman's order.[137][138][139] Philips then named Isaac as one of his own, retracted article's unnamed sources.[140]

Death Row signs Shakur

During 1995, imprisoned, impoverished, and his mother about to lose her house, Shakur had his wife Keisha Morris get word to Marion "Suge" Knight, in Los Angeles, boss of Death Row Records.[78] Reportedly, Shakur's mother promptly received $15,000.[78] After an August visit to Clinton Correctional Facility in northern New York state, Suge traveled southward to New York City to join Death Row's entourage to the 2nd Annual Source Awards ceremony.[78] Already reputed for strongarm tactics on the Los Angeles rap scene, Suge used his brief stage time mainly to belittle Sean "Puff Daddy" Combs, boss of Bad Boy Entertainment, the label then leading New York rap scene, who routinely performed with his own artists.[118][141] Before closing with a brief comment of support for Shakur,[142] Suge invited artists seeking the spotlight for themselves to join Death Row.[118][141] Eventually, Puff recalled that to preempt severe retaliation from his Bad Boy orbit, he had promptly confronted Suge, whose reply—that he had meant Jermaine Dupri, of So So Def Recordings, in Atlanta—was politic enough to deescalate the conflict.[143]

Still, among the fans, the previously diffuse rivalry between America's two mainstream rap scenes had instantly flared already.[118][142][141] And while in New York, Suge visited Uptown Records, where Puff, under its founder Andre Harrell, had started in the music business through an internship.[144] Apparently without paying Uptown, Suge obtained the releases of Puff's prime Uptown recruits Jodeci, its producer DeVante Swing, and Mary J. Blige, all then signing with Suge's management company.[144] On September 24, 1995, at a party for Dupri in Atlanta at the Platinum House nightclub, a Bad Boy circle entered a heated dispute with Suge and Suge's friend Jai Hassan-Jamal "Big Jake" Robles, a Bloods gang member and Death Row bodyguard.[118][145] According to eyewitnesses, including a Fulton County sheriff, working there as a nightclub bouncer, Puff had heatedly disputed with Suge inside the club,[118] whereas several minutes later, outside the club, it was Puff's childhood friend and own bodyguard, Anthony "Wolf" Jones, who had aimed a gun at Big Jake, fatally shot while entering Suge's car.[118][146][147]

The attorneys of Puff and his bodyguard both denied any involvement by their clients, while Puff's added that Puff had not even been with his bodyguard that night.[148] Over 20 years later, the case remains officially unresolved. Yet immediately and persistently, Suge blamed Puff, cementing the enmity between the two bosses, whose two record labels dominated the rap genre's two mainstream centers.[118][149] In the late 1990s, Southern rap's growth into the mainstream would dispel the East–West paradigm.[142] But in the meantime, in October 1995, violating his probation, Suge visited Shakur in prison again.[118] Suge posted $1.4 million bond. And with appeal of his December 1994 conviction pending, Shakur returned to Los Angeles and joined Death Row.[118] On June 4, 1996, it released the Shakur B-side "Hit 'Em Up". In this venonmous tirade, the proclaimed "Bad Boy killer" threatens violent payback on all things Bad Boy—Biggie, Puffy, Junior M.A.F.I.A., the company—and on any in New York's rap scene, like rap duo Mobb Deep and obscure rapper Chino XL, who allegedly had commented against Shakur about the dispute.

Death

On the night of September 7, 1996, Shakur was in Las Vegas, Nevada, to celebrate his business partner Tracy Danielle Robinson's birthday[150] and attended the Bruce Seldon vs. Mike Tyson boxing match with Suge Knight at the MGM Grand. Afterward in the lobby, someone in their group spotted Orlando "Baby Lane" Anderson, an alleged Southside Compton Crip, whom the individual accused of having recently in a shopping mall tried to snatch his neck chain with a Death Row Records medallion. The hotel's surveillance footage shows the ensuing assault on Anderson. Shakur soon stopped by his hotel room and then headed with Knight to his Death Row nightclub, Club 662, in a black BMW 750iL sedan, part of a larger convoy.[151]

At about 11 pm on Las Vegas Boulevard, bicycle-mounted police stopped the car for its loud music and lack of license plates. The plates were found in the trunk and the car was released without a ticket.[152] At about 11:15 pm at a stop light, a white, four-door, late-model Cadillac sedan pulled up to the passenger side and an occupant rapidly fired into the car. Shakur was struck four times: once in the arm, once in the thigh, and twice in the chest[153] with one bullet entering his right lung.[154] Shards hit Knight's head. Frank Alexander, Shakur's bodyguard, was not in the car at the time. He would say he had been tasked to drive the car of Shakur's girlfriend, Kidada Jones.[155]

Shakur was taken to the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada where he was heavily sedated and put on life support.[9] In the intensive-care unit on the afternoon of September 13, 1996, Shakur died from internal bleeding.[9] He was pronounced dead at 4:03 pm.[9] The official causes of death are respiratory failure and cardiopulmonary arrest associated with multiple gunshot wounds.[9] Shakur's body was cremated the next day. Members of the Outlawz, recalling a line in his song "Black Jesus", (although uncertain of the artist's attempt at a literal meaning chose to interpret the request seriously) smoked some of his body's ashes after mixing them with marijuana.[156][157]

In 2002, investigative journalist Chuck Philips,[158][159] after a year of work, reported in the Los Angeles Times that Anderson, a Southside Compton Crip, having been attacked by Suge and Shakur's entourage at the MGM Hotel after the boxing match, had fired the fatal gunshots, but that Las Vegas police had interviewed him only once, briefly, before his death in an unrelated shooting. Philips's 2002 article also alleges the involvement of Christopher "Notorious B.I.G." Wallace and several within New York City's criminal underworld. Both Anderson and Wallace denied involvement, while Wallace offered a confirmed alibi.[160] Music journalist John Leland, in the New York Times, called the evidence "inconclusive".[161]

In 2011, via the Freedom of Information Act, the FBI released documents related to its investigation which described an extortion scheme by the Jewish Defense League that included making death threats against Shakur and other rappers, but did not indicate a direct connection to his murder.[162][163]

Legacy and remembrance

AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine described Shakur as "the unlikely martyr of gangsta rap", with Shakur paying the ultimate price of a criminal lifestyle. Shakur was described as one of the top two American rappers in the 1990s, along with Snoop Dogg.[164] The online rap magazine AllHipHop held a 2007 roundtable at which New York rappers Cormega, citing tour experience with New York rap duo Mobb Deep, imparted a broad assessment: "Biggie ran New York. 'Pac ran America."[165] In 2010, writing Rolling Stone magazine's entry on Shakur at No. 86 among the "100 greatest artists", New York rapper 50 Cent appraised, "Every rapper who grew up in the Nineties owes something to Tupac. He didn't sound like anyone who came before him."[166] Dotdash, formerly About.com, while ranking him fifth among the greatest rappers, nonetheless notes, "Tupac Shakur is the most influential hip-hop artist of all time. Even in death, 2Pac remains a transcendental rap figure."[167] Yet to some, he was a "father figure" who, said rapper YG, "makes you want to be better—at every level."[168]

According to music journalist Chuck Philips, Shakur "had helped elevate rap from a crude street fad to a complex art form, setting the stage for the current global hip-hop phenomenon."[169] Philips writes, "The slaying silenced one of modern music's most eloquent voices—a ghetto poet whose tales of urban alienation captivated young people of all races and backgrounds."[169] Via numerous fans perceiving him, despite the questionable of his conduct, as a martyr, "the downsizing of martyrdom cheapens its use", Michael Eric Dyson concedes.[170] But Dyson adds, "Some, or even most, of that criticism can be conceded without doing damage to Tupac's martyrdom in the eyes of those disappointed by more traditional martyrs."[170] More simply, his writings, published after his death, inspired rapper YG to return to school and get his GED.[168] In 2020, California Senator and Democratic vice-presidential nominee Kamala Harris called Shakur the "best rapper alive", a mistake that she explained because "West Coast girls think 2Pac lives on".[171][172]

In 2006, Shakur's close friend and classmate Jada Pinkett Smith donated $1 million to their high school alma mater, the Baltimore School for the Arts, and named the new theater in his honor.[173][174] In 2021, Pinkett Smith honored Shakur's 50th birthday by releasing a never before seen poem she had received from the late rapper.[175]

Afeni Shakur

In 1997, Shakur's mother founded the Shakur Family Foundation. Later renamed the Tupac Amaru Shakur Foundation, or TASF, it launched with a stated mission to "provide training and support for students who aspire to enhance their creative talents." The TASF sponsors essay contests, charity events, a performing arts day camp for teenagers, and undergraduate scholarships. In June 2005, the TASF opened the Tupac Amaru Shakur Center for the Arts, or TASCA, in Stone Mountain, Georgia. Afeni also narrates the documentary Tupac: Resurrection, released in November 2003, and nominated for Best Documentary at the 2005 Academy Awards. Meanwhile, with Forbes ranking Shakur at 10th among top-earning dead celebrities in 2002,[176] Afeni Shakur launched Makaveli Branded Clothing in 2003.

Academic appraisal

In 1997, the University of California, Berkeley, offered a course led by a student titled "History 98: Poetry and History of Tupac Shakur".[177] In April 2003, Harvard University cosponsored the symposium "All Eyez on Me: Tupac Shakur and the Search for the Modern Folk Hero."[178] The papers presented cover his ranging influence from entertainment to sociology.[178] Calling him a "Thug Nigga Intellectual", an "organic intellectual",[179] English scholar Mark Anthony Neal assessed his death as leaving a "leadership void amongst hip-hop artists",[180] as this "walking contradiction" helps, Neal explained, "make being an intellectual accessible to ordinary people."[181] Tracing Shakur's mythical status, Murray Forman discussed him as "O.G.", or "Ostensibly Gone", with fans, using digital mediums, "resurrecting Tupac as an ethereal life force."[182] Music scholar Emmett Price, calling him a "Black folk hero", traced his persona to Black American folklore's tricksters, which, after abolition, evolved into the urban "bad-man". Yet in Shakur's "terrible sense of urgency", Price identified instead a quest to "unify mind, body, and spirit."[183]

Multimedia releases

In 2005, Death Row released on DVD, Tupac: Live at the House of Blues, his final recorded live performance, an event on July 4, 1996. In August 2006, Tupac Shakur Legacy, an "interactive biography" by Jamal Joseph, arrived with previously unpublished family photographs, intimate stories, and over 20 detachable copies of his handwritten song lyrics, contracts, scripts, poetry, and other papers. In 2006, the Shakur album Pac's Life was released and, like the previous, was among the recording industry's most popular releases.[184] In 2008, his estate made about $15 million.[185]

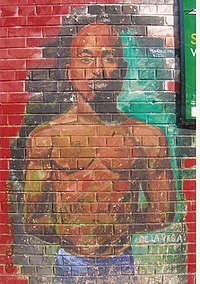

In 2014, BET explains that "his confounding mixture of ladies' man, thug, revolutionary and poet has forever altered our perception of what a rapper should look like, sound like and act like. In 50 Cent, Ja Rule, Lil Wayne, newcomers like Freddie Gibbs and even his friend-turned-rival Biggie, it's easy to see that Pac is the most copied MC of all time. There are murals bearing his likeness in New York, Brazil, Sierra Leone, Bulgaria and countless other places; he even has statues in Atlanta and Germany. Quite simply, no other rapper has captured the world's attention the way Tupac did and still does."[186]

On April 15, 2012, at the Coachella Music Festival, rappers Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre joined a Shakur hologram,[187] and, as a partly virtual trio, performed the Shakur songs "Hail Mary" and "2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted".[188][189] There were talks of a tour,[190] but Dre refused.[191] Meanwhile, the Greatest Hits album, released in 1998, and which in 2000 had left the pop albums chart, the Billboard 200, returned to the chart and reached No. 129, while also other Shakur albums and singles drew sales gains.[192] And in early 2015, the Grammy Museum opened an exhibition dedicated to Shakur.[193]

Film and stage

In 2014, the play Holler If Ya Hear Me, based on Shakur's lyrics, played on Broadway, but, among Broadway's worst-selling musicals in recent years, ran only six weeks.[194] In development since 2013, a Shakur biopic, All Eyez on Me, began filming in Atlanta in December 2015,[195] and was released on June 16, 2017, in concept Shakur's 46th birthday,[196] albeit to generally negative reviews. In August 2019, a docuseries directed by Allen Hughes, Outlaw: The Saga of Afeni and Tupac Shakur, was announced.[197]

Awards and honors

In 2003, MTV's viewers voted Shakur the greatest MC.[198] In 2005, on Vibe magazine's online message boards, a user asked others for the "Top 10 Best of All Time".[199] Vibe staff, then, "sorting out, averaging and spending a lot of energy", found, "Tupac coming in at first".[199] In 2006, MTV staff placed him second.[91] In 2012, The Source magazine ranked him fifth among all-time lyricists.[200] In 2010, Rolling Stone placed him at No. 86 among the "100 Greatest Artists".[166]

In 2007, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's "Definitive 200" albums—choices irking some otherwise[201]—placed All Eyez on Me at No. 90 and Me Against the World at No. 170.[202] In 2009, drawing praise, the Vatican added "Changes", a 1998 posthumous track, to its online playlist.[203] On June 23, 2010, the Library of Congress sent "Dear Mama" to the National Recording Registry,[204] the third rap song, after a Grandmaster Flash and a Public Enemy, ever to arrive there.[205]

In 2002, Shakur was inducted into the Hip-Hop Hall of Fame. Two years later, cable television's music network VH1 held its first ever Hip Hop Honors, where the honorees were Shakur, Run-DMC, DJ Hollywood, Kool Herc, KRS-One, Public Enemy, Rock Steady Crew, and the Sugarhill Gang.[206] On December 30, 2016, in his first year of eligibility, Shakur was nominated,[207] and on the following April 7 was among five inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[11][208]

Discography

Studio albums

- 2Pacalypse Now (1991)

- Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z... (1993)

- Me Against the World (1995)

- All Eyez on Me (1996)

Posthumous studio albums

- The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory (1996) (as Makaveli)

- R U Still Down? (Remember Me) (1997)

- Until the End of Time (2001)

- Better Dayz (2002)

- Loyal to the Game (2004)

- Pac's Life (2006)

Collaboration albums

- Thug Life: Volume 1 with Thug Life (1994)

Posthumous collaboration albums

- Still I Rise with Outlawz (1999)

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Nothing but Trouble | Himself (in a fictional context) | Brief appearance as part of the group Digital Underground |

| 1992 | Juice | Roland Bishop | First starring role |

| 1993 | Poetic Justice | Lucky | Co-starred with Janet Jackson |

| 1993 | A Different World | Piccolo | Episode: Homie Don't Ya Know Me? |

| 1993 | In Living Color | Himself | Season 5, Episode: 3 |

| 1994 | Above the Rim | Birdie | Co-starred with Duane Martin |

| 1995 | Murder Was the Case: The Movie | Sniper | Uncredited; segment: "Natural Born Killaz" |

| 1996 | Saturday Night Special | Himself (guest host) | 1 episode |

| 1996 | Saturday Night Live | Himself (musical guest) | Episode: "Tom Arnold/Tupac Shakur" |

| 1996 | Bullet | Tank | Released one month after Shakur's death |

| 1997 | Gridlock'd | Ezekiel "Spoon" Whitmore | Released four months after Shakur's death |

| 1997 | Gang Related | Detective Jake Rodriguez | Shakur's last performance in a film |

| 2001 | Baby Boy | Himself | Archive footage |

| 2003 | Tupac: Resurrection | Himself | Archive footage |

| 2009 | Notorious | Himself | Archive footage |

| 2015 | Straight Outta Compton | Himself | Archive footage |

| 2017 | All Eyez on Me | Himself | Archive footage |

Biographical portrayals in film

| Year | Title | Portrayed by | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Too Legit: The MC Hammer Story | Lamont Bentley | Biographical film about MC Hammer |

| 2009 | Notorious | Anthony Mackie | Biographical film about the Notorious B.I.G. |

| 2015 | Straight Outta Compton | Marcc Rose[209] | Biographical film about N.W.A |

| 2016 | Surviving Compton: Dre, Suge & Michel'le | Adrian Arthur | Biographical film about Michel'le |

| 2017 | All Eyez on Me | Demetrius Shipp, Jr.[210] | Biographical film about Tupac Shakur[211] |

Documentaries

Shakur's life has been explored in several documentaries, each trying to capture the many different events during his short lifetime, most notably the Academy Award-nominated Tupac: Resurrection, released in 2003.

- 1997: Tupac Shakur: Thug Immortal

- 1997: Tupac Shakur: Words Never Die (TV)

- 2001: Tupac Shakur: Before I Wake...

- 2001: Welcome to Deathrow

- 2002: Tupac Shakur: Thug Angel

- 2002: Biggie & Tupac

- 2002: Tha Westside

- 2003: 2Pac 4 Ever

- 2003: Tupac: Resurrection

- 2004: Tupac vs.

- 2004: Tupac: The Hip Hop Genius (TV)

- 2006: So Many Years, So Many Tears

- 2015: Murder Rap: Inside the Biggie and Tupac Murders

- 2017: Who killed Tupac?

- 2017: Who Shot Biggie & Tupac?

- 2018: Unsolved: Murders of Biggie and Tupac?

See also

- List of best-selling music artists

- List of best-selling music artists in the United States

- List of murdered hip hop musicians

- List of number-one albums (United States)

- List of number-one hits (United States)

- List of awards and nominations received by Tupac Shakur

- List of artists who reached number one in the United States

References

- ^ Lynch, John (September 13, 2017). "The incredible career rise and tragic murder of Tupac Shakur, who died 21 years ago". Business Insider. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ Bruck, Connie (June 29, 1997). "The Takedown of Tupac". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Tupac Shakur – Thug Angel (The Life of an Outlaw). 2002.

- ^ Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C., eds. (February 28, 2010). Encyclopedia of African American History. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 254–257. ISBN 9781851097692.

- ^ Edwards, Paul (2009). How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC. Chicago Review Press. p. 330.

- ^ Jay-Z (2011). Bailey, Julius (ed.). Essays on Hip Hop's Philosopher King. McFarland & Company. p. 55. ISBN 978-0786463299.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Huey, Steve (n.d.). "2Pac – All Eyez on Me". AllMusic. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Planas, Antonio (April 7, 2011). "FBI outlines parallels in Notorious B.I.G., Tupac slayings". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on April 11, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Koch, Ed (October 24, 1997). "Tupac Shakur's Death Certificate Details". numberonestars. Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ "Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur To Be Inducted Into Hip-Hop Hall Of Fame". December 30, 2006. Archived from the original on December 30, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Rock and Roll Hall of Fame taps Tupac, Journey, Pearl Jam". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "100 Greatest Artists". Rolling Stone. December 3, 2010. Archived from the original on December 6, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ Hoye, Jacob (2006). Tupac: Resurrection. Atria. p. 30. ISBN 0-7434-7435-X.

- ^ Scott, Cathy (October 2, 1996). "22-year-old arrested in Tupac Shakur killing". Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Tupac Coroner's Report". Cathy Scott. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ^ Bass, Debra D. (September 4, 1997). "Book chronicling Shakur murder set to hit stores". Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Walker, Charles F. (February 26, 2014). "Tupac Shakur and Tupac Amaru". Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ Cline, Sarah. "Colonial and Neocolonial Latin America (1750–1900)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ^ "Exclusive: Mopreme Shakur Talks Tupac; Rapper's B-Day Celebrated". AllHipHop.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "Rare Interview With Tupac's Biological Father". Power 107.5. December 30, 2013. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016.

- ^ Scott, Cathy (2002). The Killing of Tupac Shakur. Las Vegas, Nevada: Huntington Press. ISBN 978-0929712208.

- ^ "Afeni Shakur" (PDF). 2Pac Legacy. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sullivan, Randall (January 3, 2003). LAbyrinth: A Detective Investigates the Murders of Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G., the Implication of Death Row Records' Suge Knight, and the Origins of the Los Angeles Police Scandal. New York City: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3971-X.

- ^ "Geronimo Pratt: Black Panther leader who spent 27 years in jail for a crime he did not commit". The Independent. October 23, 2011.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (June 3, 2011). "Elmer G. Pratt, Jailed Panther Leader, Dies at 63". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Lewis, John (September 2016). "Tupac Was Here". Baltimore Magazine. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ King, Jamilah (November 15, 2012). "Art and Activism in Charm City: Five Baltimore Collectives That Are Facing Race". Colorlines. ARC. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ Case, Wesley (March 31, 2017). "Tupac Shakur in Baltimore: Friends, teachers remember the birth of an artist". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Philips, Chuck (October 25, 1995). "Tupac Shakur: 'I am not a gangster'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ Bastfield, Darrin Keith (2002). Back in the Day: My Life and Times with Tupac Shakur. Da Capo Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-345-44775-3.

- ^ Bastfield 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Golus, Carrie (December 28, 2006). Tupac Shakur. Lerner Publications. ISBN 9780822566090. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Tupac's poem "Jada" appears in his book The Rose That Grew from Concrete, which also includes a poem dedicated to her, "The Tears in Cupid's Eyes".

- ^ Wallace, Irving (2008). The intimate sex lives of famous people (Rev. ed.). Port Townsend, Washington: Feral House. ISBN 978-1932595291. OCLC 646836355.

- ^ Monjauze, Molly (2008). Tupac remembered. San Francisco Chronicle. ISBN 9781932855760. OCLC 181069620.

- ^ "Happy birthday to our brother and comrade, #TupacShakur! This is his Young Communist League membership card from when he lived in Baltimore, Maryland. #RestInPower #SolidarityForever". Twitter. Communist Party USA. June 17, 2019. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Farrar, Jordan (May 13, 2011). "Baltimore students protest cuts". . Chicago, Illinois: Long View Publishing Co. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ^ Billet, Alexander (October 15, 2011). "'And Still I See No Changes': Tupac's legacy 15 years on". greenleft.org. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ^ Bastfield 2002, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Brown, Preezy (November 12, 2016). "How '2Pacalypse Now' Marked The Birth Of A Rap Revolutionary". Vibe. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Back 2 the Essence: Friends and Families Reminisce over Hip-hop's Fallen Sons". Vibe. Vol. 7 no. 8. New York City. October 1999. pp. 100–116 [103]. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ Marriott, Michel; Brooke, James; LeDuff, Charlie; Lorch, Donatella (September 16, 1996). "Shots Silence Angry Voice Sharpened by the Streets". The New York Times. pp. A–1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ In an English class, Tupac wrote the paper "Conquering All Obstacles", which says, in part, "our raps, not the sorry story raps everyone is so tired of. They are about what happens in the real world. Our goal is, have people relate to our raps, making it easier to see what really is happening out there. Even more important, what we may do to better our world" [Cliff Mills, Tupac (New York: Checkmark, 2007)].

- ^ Meara, Paul (November 4, 2015). "That Time Tupac Visited Mike Tyson in Prison". BET. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ Grow, Kory (June 23, 2014). "Read Tupac Shakur's Heartfelt Letter to Public Enemy's Chuck D". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ Smithfield, Brad (February 4, 2017). "Jim Carrey wrote humorous letters to Tupac to cheer him up while in prison". Vintage News. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ "2Pac – KMEL 1996 Full Interview with Sway". Archived from the original on September 2, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ "What Happened (Interview by Sway)". genius.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ "Madonna confirms that she once dated Tupac Shakur". NME. March 12, 2015. Archived from the original on August 25, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Grow, Kory (July 11, 2019). "Tupac's Private Apology to Madonna Could Be Yours for $100,000". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Golus, Carrie (August 1, 2010). Tupac Shakur: Hip-Hop Idol. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7613-5473-4.

- ^ "Tupac's Ex-Wife Does Interview". Tupac-online.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ "Love is Not Enough: 2Pac's Ex-Wife, Keisha Morris". XXL. New York City: Townsquare Media. September 15, 2011. Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Kam (March 12, 2009). "Rashida Jones: The I Love You, Man Interview". LA Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ Freeman, Hadley (February 14, 2014). "Rashida Jones: 'There's more than one way to be a woman and be sexy'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016.

- ^ Anson, Robert Sam (March 1997). "To Die Like A Gangsta". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ The album is subtitled Volume 1 since Thug Life's roster had been intended to grow and evolve over time.

- ^ The 2008 fire sustained by University Music Group lost, among archives of hundreds of other artists, some of Tupac's [Jody Rosen, "Here are hundreds more artists whose tapes were destroyed in the UMG fire" Archived November 23, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, June 25, 2019].

- ^ "Leila Steinberg". Assemblies in Motion. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ^ Sandy, Candace; Daniels, Dawn Marie (December 8, 2010). How Long Will They Mourn Me?: The Life and Legacy of Tupac Shakur. Random House Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 9780307757449.

- ^ "MTV – They Told Us". Archived from the original on April 23, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ Vaught, Seneca (Spring 2014). "Tupac's Law: Incarceration, T.H.U.G.L.I.F.E., and the Crisis of Black Masculinity". Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men. 2 (2): 93–94. doi:10.2979/spectrum.2.2.87. S2CID 144439620. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Philips, Chuck (September 13, 2012). "Tupac Shakur Interview 1995". The Chuck Philips Post. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Sami, Yenigun (July 19, 2013). "20 Years Ago, Tupac Broke Through". National Public Radio.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ "2Pac – Album chart history". Billboard. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "Remebering Tupac: His Musical Legacy and His Top Selling Albums". Atlantapost.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Thug Life: Vol. 1 (CD). 1994.

- ^ "2Pac – Out On Bail (live 1994)". YouTube. January 8, 2007. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2012.[unreliable source?]

- ^ "Timeline: 25 Years of Rap Records". BBC News. October 11, 2004. Archived from the original on March 30, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ "Dear Mama (US Single #1) at AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 20, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ "RIAA – Gold & Platinum – May 13, 2009 : Search Results – 2 Pac". RIAA. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ "So Many Tears (EP) at AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ^ "Temptations (CD/Cassette Single) at AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ^ Appleford, Steve (April 1, 1996). "It's a Soul Train Awards Joy Ride for TLC, D'Angelo". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Tupac Month: 2Pac's Discography". Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ "Tupac Shakur Says He "Wrote Only One Song In Jail" In Post-Prison Interview From 1995". hiphopdx.com. August 13, 2014. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016.

- ^ Au, Wagner James (December 11, 1996). "Yo, Niccolo!". Salon. San Francisco, California. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Westhoff, Ben (September 12, 2016). "How Tupac and Biggie went from friends to deadly rivals". Vice.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ For some backstory, see Nina Bhadreshwar's apparently selfpublished How to Survive Puberty at 25 (Central Milton Keynes, UK: AuthorHouse, 2008), p 242 Archived September 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. N.b., this Death Row Uncut magazine is apparently unrelated to the video recording, also titled Death Row Uncut, that Death Row Records would release [Jenson Karp, Kanye West Owes Me $300: And Other True Stories from a White Rapper Who Almost Made It Big (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2017), pp 110 Archived September 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine–[https://web.archive.org/web/20200915031850/https://books.google.com/books?id=X5uVDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA111 Archived September 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Pocklington, Rebbeca (October 5, 2015). "Tupac Shakur wrote about starting a 'new chapter' in handwritten letter from jail, now selling for $225,000". Daily Mirror. London, UK. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016 – via Trinity Mirror.

- ^ Cummings, Moriba (May 8, 2016). "Tupac Talks Quad Studios Shooting in Kevin Powell Interview". BET. Washington, DC: Viacom. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ XXL Magazine, October 2004, p. 104.

- ^ Phillips, Chuck (July 31, 2003). "As Associates Fall, Is 'Suge' Knight Next?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015.

- ^ "Maxwell, Tupac Top Soul Train Awards". E! Online. March 7, 1997. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ "24th American Music Awards". Rock on the Net. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "RIAA – Gold & Platinum". Riaa.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ "RIAA – Gold & Platinum Searchable Database – March 09, 2015". riaa.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ "Music News, Interviews, Pics, and Gossip: Yahoo! Music". Ca.music.yahoo.com. April 20, 2011. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ XXL Magazine, October 2003.

- ^ "The Greatest Hip-Hop Albums Of All Time". MTV.com. March 9, 2006. Archived from the original on May 7, 2005. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Greatest MCs Of All Time". MTV.com. March 9, 2006. Archived from the original on April 13, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ XXL Magazine, October 2006.

- ^ "Tupac The Workaholic. (MYCOMEUP.COM)". YouTube. February 11, 2010. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2012.[unreliable source?]

- ^ The Don Killuminati chart peaks on AllMusic.

- ^ "All Eyes on Shakur's 'Don Killuminati'". Los Angeles Times. October 23, 1997. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ "Recording Industry Association of America". RIAA. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ "2Pac biography". Alleyezonme.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ "Gridlock'd". Entertainment Weekly. January 31, 1997. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "Gang Related". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 4, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Markman, Rob (May 30, 2013). "Tupac Would Have 'Outshined' 'Menace II Society,' Director Admits". MTV. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ Tate, Greg (June 26, 2001). "Sex & Negrocity by Greg Tate". Villagevoice.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2005. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ "FILM". rapbasement.com. April 10, 2008. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pareles, Jon (September 14, 1996). "Tupac Shakur, 25, Rap Performer Who Personified Violence, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ "Marin slaying case against rapper opens". San Francisco Chronicle. November 3, 1995. Archived from the original on April 12, 2013.

- ^ "Settlement in Rapper's Trial for Boy's Death". San Francisco Chronicle. November 8, 1995. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013.

- ^ Smothers, Ronald (November 2, 1993). "Rapper Charged in Shootings of Off-Duty Officers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Shakur's Estate Hit With Default Claim Over Shooting". MTV News. July 20, 1998. Archived from the original on January 27, 2002. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ "Rapper Tupac Shakur to face assault charge". Ocala Star-Banner. September 9, 1994. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Rapper sentenced for assault". The Argus. November 1, 1994. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Sullivan 2003, p. 80.

- ^ "Tupac Shakur Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Gonzalez, Victor (May 10, 2012). "TUPAC'S TEMPER: FIVE GREATEST FREAKOUTS, FROM MTV TO JAIL TIME". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ TBTEntGroup on (March 7, 2012). "Tupac Shakur interview with "The Arsenio Hall Show" in 1994 [VIDEO]". Hip-hopvibe.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ James, George (February 8, 1995). "Rapper Faces Prison Term For Sex Abuse". The New York Times. p. B1. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ Olan, Helaine (February 8, 1995). "Rapper Shakur Gets Prison for Assault". Los Angeles Times. p. A4.

- ^ "Rapper Is Sentenced to 120 Days in Jail". The New York Times. April 15, 1996. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ "Jail Term Put On Hold For Rapper Tupac Shakur". MTV. June 8, 1996. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Parker, Derrick; Diehl, Matt (2007). Notorious C.O.P.: The Inside Story of the Tupac, Biggie, and Jam Master Jay Investigations from the NYPD's First "Hip-Hop Cop". New York: St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 113–116. ISBN 9781429907781. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Jones, Charisse (December 1, 1995). "Rapper slain after chase in Queens". The New York Times. p. B 3. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn (2019). "Jam Master Jay". In Goldsmith, M.; Fonseca, Anthony J. (eds.). Hip Hop around the World: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. p. 364. ISBN 9780313357596. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Rodriguez, Jason (September 2011). "Pit of snakes". XXL Magazine. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (January 23, 2017). "Haitian Jack hip-hop miniseries in the works (exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Wolff, Craig (November 20, 1993). "Rap performer is charged In Midtown sex attack". The New York Times. p. §1:25. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Metzler, David (Director) (2017). Who Shot Biggie & Tupac? [interview with "Haitian Jack"]. Interviewed by Soledad O'Brien; Ice-T. USA: Critical Content., premiered on television September 24, 2017, by Fox Broadasting Company.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Samaha, Albert (October 28, 2013). "James Rosemond, Hip-Hop Manager Tied to Tupac Shooting, Gets Life Sentence for Drug Trafficking". Village Voice. New York City. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "Rap Artist Tupac Shakur Shot in Robbery". The New York Times. New York City. November 30, 1994. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017.

- ^ Riggs, Larry (February 5, 2009). "Today In Entertainment History: February 6". digtriad.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- ^ Stewart, Alison (March 18, 2008). "What Did Sean 'Puffy' Combs Know?". Npr.org. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (October 11, 2012). "Commentary on 1995 Tupac Recordings". chuckphilipspost.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "Tupac Shakur Interview 1995 « Chuck Philips PostChuck Philips Post". August 28, 2013. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Tupac and Biggie's battle songs". Los Angeles Times. March 17, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ Rodriguez, Jayson. "Game Manager Jimmy Rosemond Recalls Events The Night Tupac Was Shot, Says Session Was 'All Business'". MTV News. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ 2Pac (Ft. Outlawz) – Hit 'Em Up, retrieved June 1, 2021

- ^ The Notorious B.I.G. – Who Shot Ya?, retrieved June 1, 2021

- ^ Philips, Chuck (June 12, 2012). "James "Jimmy Henchman" Rosemond Implicated Himself in 1994 Tupac Shakur Attack: Court Testimony". Village Voice. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ "Times retracts Shakur story". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. April 7, 2008. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Evans, Jennifer (June 21, 2001). "Hip hop talent agent arrested charged with operating drug ring". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ KTLA News (July 13, 2012). "Convicted Killer Confesses to Shooting West Coast Rapper Tupac Shakur". The Courant. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Watkins, Greg (June 15, 2011). "Exclusive: Jimmy Henchman Associate Admits to Role in Robbery/Shooting of Tupac; Apologizes To Pac & B.I.G.'s Mothers". Allhiphop.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "Chuck Philips demands apology on Tupac Shakur". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ramirez, Erika (December 4, 2014). "Throwback Thursday: Suge Knight Disses Diddy at 1995 Source Awards". Billboard.com. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Simmons, Nadirah (August 3, 2016). "Today in 1995: The 2nd Annual Source Awards makes hip hop history". The Source. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Barry, Peter A. (November 30, 2016). "Diddy claims he confronted Suge Knight after infamous 1995 Source Awards speech". XXL Magazine. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sullivan 2003, noting Newsweek report Archived September 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Egbert, Bill (February 27, 2001). "Hip Hype & Rival Rap, by Bill Egbert". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on July 4, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (January 17, 2001). "Possible link of 'Puffy' Combs to fatal shooting being probed". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 5, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Noel, Peter (February 13, 2001). "Big bad Wolf". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Dansby, Andrew (January 18, 2001). "Report infuriates Puffy camp". RollingStone.com. Penske Business Media, LLC. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ During the 1995 Source Awards, the rap genre's bicoastal paradigm was still so entrenched that when rap duo Outkast, from Atlanta, won as best new group, the audience booed, setting up Outkast member Andre's momentous response, ultimately, "The South got something to say" [N Simmons, "Today in 1995: The 2nd Annual" Archived July 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, The Source, August 3, 2016].

- ^ Miller, Matt; Rahimi, Gobi M. (September 6, 2016). "I Spent Six Days Protecting Tupac on His Deathbed". Esquire. New York City: Hearst Magazines. Archived from the original on January 6, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ "September 1996 Shooting and Death". madeira.hccanet.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "Tupac Shakur LV Shooting –". Thugz-network.com. September 7, 1996. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ "Rapper Tupac Shakur Gunned Down". MTV News. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Detailed information on the fatal shooting". AllEyezOnMe. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ "Tupac Shakur: Before I Wake". film.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "Tupac's life after death". Smh.com.au. September 13, 2006. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ O'Neal, Sean (August 30, 2011). "Yes, the Outlawz smoked Tupac's ashes". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (September 6, 2002). "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (September 7, 2002). "Who killed Tupac Shakur?: Part 2". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Notorious B.I.G.'s Family 'Outraged' By Tupac Article". Streetgangs.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2003. Retrieved July 28, 2010.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Leland, John (October 7, 2002). "New Theories Stir Speculation On Rap Deaths". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ "Unsealed FBI Report on Tupac Shakur". Vault.fbi.gov. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Service, Haaretz (April 14, 2011). "FBI files on Tupac Shakur murder show he received death threats from Jewish gang". Haaretz.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (n.d.). "2Pac biography". AllMusic. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Chris "Milan" (editor), with Erik Gilroy (reporter), and AllHipHop interviewers, "Tupak Shakur: A roundtable discussion", featuring Pudgee that Phat Bastard, Buckshot, Chino XL, Adisa Bankjoko, Cormega, and DJ Fatal, AllHipHop.com, March 5, 2007: "Cormega: A lot of people think that it was about Biggie on the East Coast and 'Pac on the West Coast. It wasn't like that. Big ran New York. 'Pac ran America. I was in a club with Mobb Deep in North Carolina and n***as in the crowd were shouting "Makaveli!" This is on the East Coast! That shows you how powerful his influence was" archived January 7, 2012].

- ^ Jump up to: a b 50 Cent, "86: Tupac Shakur", in Rolling Stone, editors, "100 greatest artists: The Beatles, Eminem and more of the best of the best" Archived June 18, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, RollingStone.com, Penske Business Media, LLC, December 3, 2010, archived May 23, 2012.

- ^ Adaso, Henry, "The 50 greatest rappers of all time: They've shown originality, longevity, cultural impact, vocal presence" Archived May 31, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, .com, Dotdash, updated December 13, 2018, formerly Henry Adaso, "50 greatest MCs of our time (1987–2007)", Rap.About.com, March 11, 2011, archived March 9, 2012, when Tupac Shakur placed 7th.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crates, Jake (February 3, 2015). "YG Says Tupac Has Inspired His Return To School; Calls Pac A Father Figure For Many (AUDIO)". AllHipHop.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Philips, Chuck (January 30, 2015). "Who killed Tupac Shakur? —part 1 of 2". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dyson, Michael Eric (2001). Holler If You Hear Me: Searching for Tupac Shakur. New York: Basic Civitas Books. p. 264. ISBN 9780786735488. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2020.