Typee

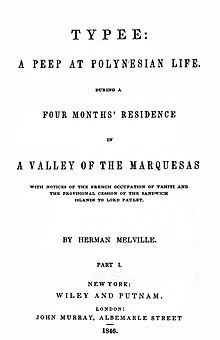

First American edition title page | |

| Author | Herman Melville |

|---|---|

| Country | United States, England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Travel literature |

| Published |

|

| Media type | |

| Followed by | Omoo |

Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life is the first book by American writer Herman Melville, published in the early part of 1846, when Melville was 26 years old. Considered a classic in travel and adventure literature, the narrative is based on the author's actual experiences on the island Nuku Hiva in the South Pacific Marquesas Islands in 1842, supplemented with imaginative reconstruction and research from other books. The title comes from the valley of Taipivai, once known as Taipi.[1] Typee was Melville's most popular work during his lifetime; it made him notorious as the "man who lived among the cannibals".[2]

Background[]

The book delivers quite a wild tale and from the beginning there were questions about whether any of it could possibly be true. Prior to the London edition of the book appearing within the Colonial and Home Library series (nonfiction accounts of foreigners in exotic places), the publisher John Murray required reassurance that Melville's experiences were first-hand.[3]

Not long after the initial publication of the book, many of the events described were corroborated by Melville's fellow castaway, ("Toby"). Additionally, an affidavit was found from the ship's captain that corroborated that both men did indeed desert the ship on the island in the summer of 1842.[2]

Typee attempts to be something of a work of proto-anthropology. Melville continually admits vast ignorance of the culture and language he is describing while also trying to bolster and supplement his own experiences with a great deal of other reading and research. He also has a tendency to employ a fair amount of hyperbole and attempts at humor. The book includes some dated and cringe-inducing lines and a few recent scholars have dedicated themselves to questioning the basic factuality of Melville's account.[4] For instance, the length of stay on which Typee is based is presented as four months in the narrative and this was likely an extension and exaggeration of Melville's actual stay on the island. There is also not known to have ever been a lake on the island where Melville might have gone canoeing with Fayaway, as described in the book. [2] [5]

Critical response[]

Typee's narrative expresses a great deal of sympathy for the so-called savages, and even interrogates the use of that word, while focusing the most criticism on European marauders and various missionaries' attempts to evangelize:

It may be asserted without fear of contradictions that in all the cases of outrages committed by Polynesians, Europeans have at some time or other been the aggressors, and that the cruel and bloodthirsty disposition of some of the islanders is mainly to be ascribed to the influence of such examples.

[The] voluptuous Indian, with every desire supplied, whom Providence has bountifully provided with all the sources of pure and natural enjoyment, and from whom are removed so many of the ills and pains of life—what has he to desire at the hands of Civilization? Will he be the happier? Let the once smiling and populous Hawaiian islands, with their now diseased, starving, and dying natives, answer the question. The missionaries may seek to disguise the matter as they will, but the facts are incontrovertible. CH 4

The Knickerbocker called Typee "a piece of Münchhausenism."[6] New York publisher Evert Augustus Duyckinck wrote to Nathaniel Hawthorne that "it is a lively and pleasant book, not over philosophical perhaps."[7] In 1939, Charles Robert Anderson published Melville in the South Seas in which he elaborated on a number of Melville's likely sources in supplementing his work and also documented the existence of an affidavit from the Captain of the Acushnet.[8] If the date provided by Captain can be considered accurate, Anderson concludes that Melville's stay in the "Typee Valley" part of the island would have been merely "four weeks, or possible eight weeks at the most."[9] However, in trying to determine the end date of Melville's stay, Anderson primarily relies on Melville's own internal accounts of various events, for instance that he was rescued from the valley on a "Monday." In summing up his view of Typee, Anderson writes:

For the general student of Melville, the detailed analysis and verification of these matters... probably reveals an accuracy scarcely to be expected. Without hesitation it can be said that in general this volume presents faithful delineation of the island life and scenery in precivilization Nukahiva, with the exception of numerous embellishments and some minor errors...[10]

All of the initial back and forth which Melville experienced regarding the factuality of Typee may have had a chastening effect on him, as Anderson considers his next work, the book's sequel Omoo, "the most strictly autobiographical of all Melville's works."[11] But this second book also seems to have met with some skepticism, so that for his third book Mardi, Melville declares in the preface that he has decided to write a work of fiction under the supposition (half-joking) he might finally be believed:

Not long ago, having published two narratives of voyages in the Pacific, which, in many quarters, were received with incredulity, the thought occurred to me, of indeed writing a romance of Polynesian adventure, and publishing it as such; to whether, the fiction might not, possibly be received for a verity: in some degree the reverse of my previous experience.[12]

Publication history[]

Typee was published first in London by John Murray on February 26, 1846, and then in New York by Wiley and Putnam on March 17, 1846.[13] It was Melville's first book, and made him one of the best-known American authors overnight.[14]

The same version was published in London and New York in the first edition; however, Melville removed critical references to missionaries and Christianity from the second U.S. edition at the request of his American publisher. Later additions included a "Sequel: The Story of Toby" written by Melville, explaining what happened to Toby.[15]

Before Typee's publication in New York, Wiley and Putnam asked Melville to remove one sentence. In a scene in Chapter Two where the Dolly is boarded by young women from Nukuheva, Melville originally wrote:

Our ship was now given up to every species of riot and debauchery. Not the feeblest barrier was interposed between the unholy passions of the crew and their unlimited gratification.[16]

The second sentence was removed from the final version.[17]

The discovery in 1983 of thirty more pages from Melville’s working draft manuscript led Melville scholar John Bryant to challenge earlier conclusions about Melville's writing habits. He describes the versions of the draft manuscript and of the “radically different physical print versions of the book,” which amount, Bryant concludes, to “one grand, hooded mess.” Since there is no clear way to present Melville’s "final intention," his 2008 book offers a “fluid text” that allows a reader to follow the revisions. made what he called “an exciting new perspective on Melville’s writing process and culture.” [18]

The inaugural book of the Library of America series, titled Typee, Omoo, Mardi (May 6, 1982), was a volume containing Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life, its sequel Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847), and Mardi, and a Voyage Thither (1849).[19]

See also[]

- Last of the Pagans, a 1935 film adaptation of Typee

- Enchanted Island, a 1958 film adaptation of Typee

References[]

- ^ Christian, F.W., Nuku and Uia-Ei, 1895, "Notes on the Marquesans," Journal of the Polynesian Society 4(3):187-202. Page 200

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Howard (1968), p. 291-294.

- ^ Howard (1968), p. 279.

- ^ See Bibliography below

- ^ Herbert (1980), p. 159.

- ^ Miller (1956), p. 203.

- ^ Widmer (1999), p. 108.

- ^ Anderson (1939), p. 47.

- ^ Anderson (1939), p. 70.

- ^ Anderson (1939), p. 190.

- ^ Anderson (1939), p. 199.

- ^ Preface to Mardi (1849), 5

- ^ Howard (1968), p. 285.

- ^ Miller (1956), p. 4.

- ^ Melville (1968), p. Sequel.

- ^ Melville (1968), p. 15.

- ^ Nelson (1981), 187

- ^ Bryant (2008), p. 26-30.

- ^ Melville, Herman (1982). Typee, Omoo, Mardi (Library of America ed.). G. Thomas Tanselle. ISBN 978-0-940450-00-4.

Bibliography[]

- Anderson, Charles Roberts (1939). Melville in the South Seas. Columbia University Press.

- Bryant, John (2008). Melville Unfolding: Sexuality, Politics, and the Versions of Typee: A Fluid-Text Analysis, with an Edition of the Typee Manuscript. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472115921.

- Herbert, T. Walter (1980). Marquesan Encounters: Melville and the Meaning of Civilization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674550668.

- Howard, Leon (1968), "Historical Note", in Melville, Herman (ed.), Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life the Writings of Herman Melville Vol. 1, Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, pp. 277–302, ISBN 9780810101593

- Melville, Herman (1968). Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life. 1. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810101593.

- ——— (1996). Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life During a Four Months' Residence in a Valey of the Marquesas. Introduction, Explanatory Commentary, and Appendices by John Bryant. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140434880.

- Miller, Perry (1956). The Raven and the Whale: The War of Words and Wits in the Era of Poe and Melville. New York: Harvest.

- Nelson, Randy F. (1981). The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc. ISBN 0-86576-008-X

- Stern, Milton R., ed. (1982). Critical Essays on Herman Melville's Typee. Boston, Mass: G.K. Hall. ISBN 0816184453..

- Widmer, Edward L. (1999). Young America: The Flowering of Democracy in New York City. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514062-1..

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Typee at Project Gutenberg

- Typee, 1846 first edition, scanned book via Internet Archive, other later editions available.

Typee public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Typee public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Herman Melville'sTypee: A Fluid Text Edition, edited by John Bryant (University of Virginia Press).

- The Classics Illustrated comic book at the Internet Archive

- 1846 American novels

- American novels adapted into films

- Marquesan culture

- Novels by Herman Melville

- Marquesas Islands

- Novels set in Oceania

- Novels set on islands

- French Polynesia in fiction

- Novels republished in the Library of America

- Nautical fiction