University of Washington

| |

Former name | Territorial University of Washington (1861–1889) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Lux sit (Latin)[1] |

Motto in English | Let there be light |

| Type | Public flagship research university |

| Established | November 4, 1861 |

| Accreditation | NWCCU |

Academic affiliations |

|

| Endowment | $3.46 billion (2020)[2][3] |

| Budget | $7.84 billion (FY 2019)[4] |

| President | Ana Mari Cauce |

| Provost | Mark Richards |

Academic staff | 5,803 |

Administrative staff | 16,174 |

| Students | 47,571 (Fall 2019)[4] |

| Undergraduates | 31,041 (Fall 2019)[4] |

| Postgraduates | 16,530 (Fall 2019)[4] |

| Location | Seattle , Washington , United States 47°39′15″N 122°18′29″W / 47.65417°N 122.30806°WCoordinates: 47°39′15″N 122°18′29″W / 47.65417°N 122.30806°W |

| Campus | Urban, 807 acres (3.3 km2) (total) |

| Newspaper | The Daily of the University of Washington |

| Colors | Purple & Gold[5] |

| Nickname | Huskies |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I FBS – Pac-12 |

| Mascot | Harry the Husky and Dubs II (live Malamute) |

| Website | www |

| |

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub)[6] is a public research university in Seattle, Washington. Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seattle approximately a decade after the city's founding to aid its economic development. Today, the university's 703 acre main Seattle campus is in the University District, Puget Sound region of the Pacific Northwest. The university also has campuses in Tacoma and Bothell. Overall, UW encompasses over 500 buildings and over 20 million gross square footage of space, including one of the largest library systems in the world with more than 26 university libraries, as well as the UW Tower, lecture halls, art centers, museums, laboratories, stadiums, and conference centers. The university offers degrees through 140 departments in various colleges and schools, and functions on a quarter system.

Washington is a member of the Association of American Universities and is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[7] According to the National Science Foundation, UW spent $1.41 billion on research and development in 2018, ranking it 5th in the nation.[8] As the flagship institution of the six public universities in Washington state, it is known for its medical, engineering and scientific research as well as its extremely competitive computer science, engineering and business school. Additionally, Washington continues to benefit from its deep historic ties and major collaborations with numerous technology giants in the region, such as Amazon, Boeing, Nintendo, and particularly Microsoft. Paul G. Allen, Bill Gates and others spent significant time at Washington computer labs for a startup venture before founding Microsoft and other ventures.[9] The UW's 22 varsity sports teams are also highly competitive, competing as the Huskies in the Pac-12 Conference of the NCAA Division I, representing the United States at the Olympic Games, and other major competitions.[10]

The university has been affiliated with many notable alumni and faculty, including 21 Nobel Prize laureates and numerous Pulitzer Prize winners, Fulbright Scholars, Rhodes Scholars and Marshall Scholars.

History[]

Founding[]

In 1854, territorial governor Isaac Stevens recommended the establishment of a university in the Washington Territory. Prominent Seattle-area residents, including Methodist preacher Daniel Bagley, saw this as a chance to add to the city's potential and prestige. Bagley learned of a law that allowed United States territories to sell land to raise money in support of public schools. At the time, Arthur A. Denny, one of the founders of Seattle and a member of the territorial legislature, aimed to increase the city's importance by moving the territory's capital from Olympia to Seattle. However, Bagley eventually convinced Denny that the establishment of a university would assist more in the development of Seattle's economy. Two universities were initially chartered, but later the decision was repealed in favor of a single university in Lewis County provided that locally donated land was available. When no site emerged, Denny successfully petitioned the legislature to reconsider Seattle as a location in 1858.[11][12]

In 1861, scouting began for an appropriate 10 acres (4 ha) site in Seattle to serve as a new university campus. Arthur and Mary Denny donated eight acres, while fellow pioneers Edward Lander, and Charlie and Mary Terry, donated two acres on Denny's Knoll in downtown Seattle.[13] More specifically, this tract was bounded by 4th Avenue to the west, 6th Avenue to the east, Union Street to the north, and Seneca Streets to the south.

John Pike, for whom Pike Street is named, was the university's architect and builder.[14] It was opened on November 4, 1861, as the Territorial University of Washington. The legislature passed articles incorporating the university, and establishing its Board of Regents in 1862. The school initially struggled, closing three times: in 1863 for low enrollment, and again in 1867 and 1876 due to funds shortage. Washington awarded its first graduate Clara Antoinette McCarty Wilt in 1876, with a bachelor's degree in science.

19th century relocation[]

By the time Washington state entered the Union in 1889, both Seattle and the university had grown substantially. Washington's total undergraduate enrollment increased from 30 to nearly 300 students, and the campus's relative isolation in downtown Seattle faced encroaching development. A special legislative committee, headed by UW graduate Edmond Meany, was created to find a new campus to better serve the growing student population and faculty. The committee eventually selected a site on the northeast of downtown Seattle called Union Bay, which was the land of the Duwamish, and the legislature appropriated funds for its purchase and construction. In 1895, the university relocated to the new campus by moving into the newly built Denny Hall. The University Regents tried and failed to sell the old campus, eventually settling with leasing the area. This would later become one of the university's most valuable pieces of real estate in modern-day Seattle, generating millions in annual revenue with what is now called the Metropolitan Tract. The original Territorial University building was torn down in 1908, and its former site now houses the Fairmont Olympic Hotel.

The sole-surviving remnants of Washington's first building are four 24-foot (7.3 m), white, hand-fluted cedar, Ionic columns. They were salvaged by Edmond S. Meany, one of the university's first graduates and former head of its history department. Meany and his colleague, Dean Herbert T. Condon, dubbed the columns as "Loyalty," "Industry," "Faith", and "Efficiency", or "LIFE." The columns now stand in the Sylvan Grove Theater.[15]

20th century expansion[]

Organizers of the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition eyed the still largely undeveloped campus as a prime setting for their world's fair. They came to an agreement with Washington's Board of Regents that allowed them to use the campus grounds for the exposition, surrounding today's Drumheller Fountain facing towards Mount Rainier. In exchange, organizers agreed Washington would take over the campus and its development after the fair's conclusion. This arrangement led to a detailed site plan and several new buildings, prepared in part by John Charles Olmsted. The plan was later incorporated into the overall UW campus master plan, permanently affecting the campus layout.

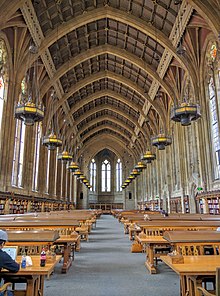

Both World Wars brought the military to campus, with certain facilities temporarily lent to the federal government. In spite of this, subsequent post-war periods were times of dramatic growth for the university.[16] The period between the wars saw a significant expansion of the upper campus. Construction of the Liberal Arts Quadrangle, known to students as "The Quad," began in 1916 and continued to 1939. The university's architectural centerpiece, Suzzallo Library, was built in 1926 and expanded in 1935.

After World War II, further growth came with the G.I. Bill. Among the most important developments of this period was the opening of the School of Medicine in 1946, which is now consistently ranked as the top medical school in the United States. It would eventually lead to the University of Washington Medical Center, ranked by U.S. News and World Report as one of the top ten hospitals in the nation.

In 1942, all persons of Japanese ancestry in the Seattle area were forced into inland internment camps as part of Executive Order 9066 following the attack on Pearl Harbor. During this difficult time, university president Lee Paul Sieg took an active and sympathetic leadership role in advocating for and facilitating the transfer of Japanese American students to universities and colleges away from the Pacific Coast to help them avoid the mass incarceration.[17] Nevertheless, many Japanese American students and "soon-to-be" graduates were unable to transfer successfully in the short time window or receive diplomas before being incarcerated. It was only many years later that they would be recognized for their accomplishments, during the University of Washington's Long Journey Home ceremonial event that was held in May 2008.

From 1958 to 1973, the University of Washington saw a tremendous growth in student enrollment, its faculties and operating budget, and also its prestige under the leadership of Charles Odegaard. UW student enrollment had more than doubled to 34,000 as the baby boom generation came of age. However, this era was also marked by high levels of student activism, as was the case at many American universities. Much of the unrest focused around civil rights and opposition to the Vietnam War.[18][19] In response to anti-Vietnam War protests by the late 1960s, the University Safety and Security Division became the University of Washington Police Department.[20]

Odegaard instituted a vision of building a "community of scholars", convincing the Washington State legislatures to increase investment in the university. Washington senators, such as Henry M. Jackson and Warren G. Magnuson, also used their political clout to gather research funds for UW. The results included an increase in the operating budget from $37 million in 1958 to over $400 million in 1973, solidifying UW as a top recipient of federal research funds in the United States. The establishment of technology giants such as Microsoft, Boeing and Amazon in the local area also proved to be highly influential in the UW's fortunes, not only improving graduate prospects[21][22] but also helping to attract millions of dollars in university and research funding through its distinguished faculty and extensive alumni network.[23]

21st century[]

In 1990, the University of Washington opened its additional campuses in Bothell and Tacoma. Although originally intended for students who have already completed two years of higher education, both schools have since become four-year universities with the authority to grant degrees. The first freshman classes at these campuses started in fall 2006. Today both Bothell and Tacoma also offer a selection of master's degree programs.

In 2012, the university began exploring plans and governmental approval to expand the main Seattle campus, including significant increases in student housing, teaching facilities for the growing student body and faculty, as well as expanded public transit options. The University of Washington light rail station was completed in March 2015,[24] connecting Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood to the UW Husky Stadium within five minutes of rail travel time.[25] It offers a previously unavailable option of transportation into and out of the campus, designed specifically to reduce dependence on private vehicles, bicycles and local King County buses.

Campus[]

UW's main campus is situated in Seattle, by the shores of Union and Portage Bays with views of the Cascade Range to the east, and the Olympic Mountains to the west. The site encompasses 703 acres (2.84 km2) bounded by N.E. 45th Street on the north, N.E. Pacific Street on the south, Montlake Boulevard N.E. on the east, and 15th Avenue N.E. on the west.

Red Square is the heart of the campus, surrounded by landmark buildings and artworks, such as Suzzallo Library, the Broken Obelisk, and the statue of George Washington. It functions as the central hub for students and hosts a variety of events annually. University Way, known locally as "The Ave", lies nearby and is a focus for much student life at the university.

North Campus[]

North Campus features some of UW's most recognized landscapes as well as landmarks, stretching from the signature University of Washington Quad directly north of Red Square to N.E. 45th Street,[26] and encompasses a number of the university's most historical academic, research, housing, parking, recreational and administrative buildings. With UW's continued growth, administrators proposed a new, multimillion-dollar, multi-phase development plan in late 2014 to refine portions of the North Campus, renovating and replacing old student housing with new LEED-certified complexes, introducing new academic facilities, sports fields, open greenery, and museums.[27][28] The UW Foster School of Business, School of Law, and the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, which houses a significant number of exhibits including a 66-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex fossil skull – one of only 15 known to exist in the world today and part of an ongoing excavation, are also located in North Campus.[29][30][31]

South Campus[]

South Campus occupies the land between Pacific Street and the Lake Washington Ship Canal. The land was previously the site of the University Golf Course but was given up to construct a building for the School of Medicine.[32] Today, South Campus is the location of UW's health sciences and natural sciences facilities, including the UW Medical Center and the Magnuson Health Sciences Center as well as locations for instruction and research in oceanography, bioengineering, biology, genome sciences, hydraulics, and comparative medicine. In 2019, the Bill & Melinda Gates Center For Computer Science & Engineering opened in South Campus.

East Campus[]

The East Campus area stretches east of Montlake Boulevard to Laurelhurst and is largely taken up by wetlands and Huskies sports facilities and recreation fields, including Husky Stadium, Hec Edmundson Pavilion, and Husky Ballpark. While the area directly north of the sports facilities is home to UW's computer science and engineering programs, which includes computer labs once used by Paul G. Allen and Bill Gates for their prior venture before establishing Microsoft,[9] the area northeast of the sports facilities is occupied by components of the UW Botanic Gardens, such as the Union Bay Natural Area, the UW Farm, and the Center for Urban Horticulture. Further east is the Ceramic and Metal Arts Building and Laurel Village, which provides family housing for registered full-time students. East Campus is also the location of the UW light rail station.

West Campus[]

West Campus consists of mainly modernist structures located on city streets, and stretches between 15th Avenue and Interstate 5 from the Ship Canal, to N.E. 41st Street. It is home to the College of Built Environments, School of Social Work, Fishery Sciences Building, UW Police Department as well as many of the university's residence halls and apartments, such as Stevens Court, Mercer Court, Alder Hall, and Elm Hall.

Organization and administration[]

Governance[]

University of Washington's President Ana Mari Cauce was selected by the Board of Regents, effective October 13, 2015.[33] On November 12, 2015, the Board of Regents approved a five-year contract for Cauce, awarding her yearly compensation of $910,000. Cauce's compensation package includes an annual salary of $697,500, $150,000 per year in deferred compensation, an annual $50,500 contribution into a retirement account, and a $12,000 annual automobile allowance.[34] She was the Interim President before her appointment, fulfilling the position left vacant by the previous President Michael K. Young when he was announced to be Texas A&M University's next President on February 3, 2015.[35] Phyllis Wise, who had served at UW as Provost and Executive Vice President, and as Interim President for a year, was named the Chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in August 2011.[36]

The university is governed by ten Regents, one of whom is a student. Its most notable former regent is likely William H. Gates, Sr., the father of Bill Gates. The undergraduate student government is the Associated Students of the University of Washington (ASUW) and the graduate student government is the Graduate and Professional Student Senate (GPSS).

Finances[]

In 2017 the university reported $4.893 billion in revenues and $5.666 billion in expenses, resulting in an operating loss of $774 million. This loss was offset by $342 million in state appropriations, $443 million in investment income, $166 million in gifts, and $185 million of other non-operating revenues.[37] Thus, the university's net position increased by $363 million in 2017.[37]

Endowment[]

Endowed gifts are commingled in the university's Consolidated Endowment Fund, managed by an internal investment company at an annual cost of approximately $6.2 million.[37] The university reported $443.383 million of investment income in fiscal year 2017.[37] As of 31 December 2017 the value of the CEF was $3.361 billion, with $686 million in Emerging Markets Equity, $1.235 billion in Developed Markets Equity, $383 million in Private Equity, $185 million in Real Assets, $54 million in Opportunistic, $535 million in Absolute Return, and $283 million in Fixed Income.[38]

Major projects[]

Major recent spending includes $131 million on the UW Animal Research and Care Facility, $72 million on the Nano-engineering and Sciences Building, $61 million building on the Workday HR & Payroll System, $50 million on the Denny Hall Renovation, $44 million on the West Campus Utility Plant, $26 million on the UW Medical Center Expansion Phase 2, $25 million on the UW Tacoma Urban Solutions Center, and $21 million on the UW Police Department.[37] The initial contract for Workday was for $27 million, so the total $61 million cost represents a $34 million cost overrun.[39] As of 28 April 2018, the university has nearly $1 billion in new construction underway.[40]

Sustainability[]

Environmental sustainability has long been a major focus of the university's Board of Regents and Presidents. In February 2006, the UW joined a partnership with Seattle City Light as part of their Green Up Program, ensuring that all of Seattle campus' electricity is supplied by and purchased from renewable sources.[41] In 2010, then UW President Emmert furthered the university's efforts with a host of other universities across the U.S., and signed the American College & University Presidents' Climate Commitment.[42] UW created a Climate Action Team,[43] as well as an Environmental Stewardship Advisory Committee (ESAC) which keeps track of UW's greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint.[44] Policies were enacted with environmental stewardship in mind, and institutional support was provided to assist with campus sustainability.[45]

Additionally, UW's Student Housing and Food Services (HFS) office has dedicated several million dollars annually towards locally produced, organic, and natural foods. HFS also ceased the use of foam food containers on-campus, and instead opted for compostable cups, plates, utensils, and packaging whenever possible. New residence halls planned for 2020 are also expected to meet silver or gold LEED standards.[46] Overall, the University of Washington was one of several universities to receive the highest grade, "A-", on the Sustainable Endowments Institute's College Sustainability Report Card in 2011.[47] The university was one of 15 Overall College Sustainability Leaders, among the 300 institutions surveyed.[48]

Academics and research[]

The university offers bachelor's, master's and doctoral degrees through its 140 departments, themselves organized into various colleges and schools.[49] It also continues to operate a Transition School and Early Entrance Program on campus, which first began in 1977.[50]

Rankings and reputation[]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

UW has been listed as a "Public Ivy" in Greene's Guides since 2001,[62] and is an elected member of the American Association of Universities.[63] Among the faculty by 2012, there have been 151 members of American Association for the Advancement of Science, 68 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 67 members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 53 members of the Institute of Medicine, 29 winners of the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers, 21 members of the National Academy of Engineering, 15 Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigators, 15 MacArthur Fellows, 9 winners of the Gairdner Foundation International Award, 5 winners of the National Medal of Science, 7 Nobel Prize laureates, 5 winners of Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research, 4 members of the American Philosophical Society, 2 winners of the National Book Award, 2 winners of the National Medal of Arts, 2 Pulitzer Prize winners, 1 winner of the Fields Medal, and 1 member of the National Academy of Public Administration.[64][65][66] Among UW students by 2012, there were 136 Fulbright Scholars, 35 Rhodes Scholars, 7 Marshall Scholars and 4 Gates Cambridge Scholars.[67] UW is recognized as a top producer of Fulbright Scholars, ranking 2nd in the US in 2017.[68]

The Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) has consistently ranked UW as one of the top 20 universities worldwide every year since its first release.[69] In 2019, UW ranked 14th worldwide out of 500 by the ARWU, 26th worldwide out of 981 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings, and 28th worldwide out of 101 in the Times World Reputation Rankings.[70] Meanwhile, QS World University Rankings ranked it 68th worldwide, out of over 900.[71]

U.S. News & World Report ranked UW 8th out of nearly 1,500 universities worldwide for 2021, with UW's undergraduate program tied for 58th among 389 national universities in the U.S. and tied for 19th among 209 public universities.[72]

In 2019, it ranked 10th among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[73] In 2017, the Leiden Ranking, which focuses on science and the impact of scientific publications among the world's 500 major universities, ranked UW 12th globally and 5th in the U.S.[74][75]

In 2019, Kiplinger magazine's review of "top college values" named UW 5th for in-state students and 10th for out-of-state students among U.S. public colleges, and 84th overall out of 500 schools.[76] In the Washington Monthly National University Rankings UW was ranked 15th domestically in 2018, based on its contribution to the public good as measured by social mobility, research, and promoting public service.[77]

Admissions[]

The university's undergraduate admissions process is rated 91/99 by the Princeton Review meaning highly selective,[78][79] and is classified "more selective" by the U.S. News & World Report.[80] For Fall 2019, 23,606 (51.8%) were accepted out of 45,584 applications.[81] Among the 6,984 admitted freshman students who then officially enrolled for Fall 2019, the middle 50% of SAT scores ranged from 1240 to 1440, out of 1600. More specifically, the middle 50% ranged from 600 to 700 for evidence-based reading and writing, and 620–770 for math.[82][83] ACT composite scores for the middle 50% ranged from 27 to 33, out of 36.[82] The middle 50% of admitted GPA ranged from 3.72 to 3.95, out of 4.0.[81]

The university uses capacity constrained majors,[84] a gate-keeping process that requires most students to apply to an internal college or faculty. New applications are usually considered once or twice annually, and few students are admitted each time.[85] The screening process is often stringent, largely being based on cumulative academic performance, recommendation letters and extracurricular activities.[86] Capacity constrained majors have been criticized for delaying graduation and forcing good students to reroute their education.[87]

Research[]

UW's research budget consistently ranks among the top 5 in both public and private universities in the United States.[88][89] It surpassed the $1.0 billion research budget milestone in 2012,[90] and university endowments reached almost $3.0 billion by 2016.[91] UW is the largest recipient of federal research funding among public universities, and currently ranks top 2nd among all public and private universities in the nation.[92]

In 2014, the University of Washington School of Oceanography and the UW Applied Physics Laboratory completed the construction of the first high-power underwater cabled observatory in the United States.

To promote equal academic opportunity, especially for people of low income, UW launched Husky Promise in 2006. Families of income up to 65 percent of state median income or 235 percent of the federal poverty level are eligible. With this, up to 30 percent of undergraduate students may be eligible. The cut-off income level that UW set is the highest in the nation, making top-quality education available to more people. Then UW President, Mark Emmert, simply said that being "elitist is not in our DNA".[93][94] "Last year, the University of Washington moved to a more comprehensive approach [to admissions], in which the admissions staff reads the entire application and looks at grades within the context of the individual high school, rather than relying on computerized cutoffs."[95]

UW was the host university of ResearchChannel program (now defunct), the only TV channel in the United States dedicated solely for the dissemination of research from academic institutions and research organizations.[96] Participation of ResearchChannel included 36 universities, 15 research organizations, two corporate research centers and many other affiliates.[97]

Alan Michelson, now Head of the Built Environments Library at UW Seattle, manages the Pacific Coast Architecture Database (PCAD), which Michelson started in 2002 while he worked as Architecture and Design Librarian at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The PCAD serves as a searchable public database detailing significant but importantly, also lesser-known and -lauded designers, buildings and structures, and partnerships, with links including to bibliographic literature.[98]

In 2019, iDefense reported that Chinese hackers had launched cyberattacks on dozens of academic institutions in an attempt to gain information on technology being developed for the United States Navy.[99] Some of the targets included the University of Washington.[99] The attacks have been underway since at least April 2017.[99]

Student life[]

| Student Body | Washington | U.S. Census | |

|---|---|---|---|

| African American | 4.0% | 3.6% | 12.0% |

| Asian American | 25.4% | 7.2% | 4.7% |

| White American | 40.3% | 72.5% | 63.7% |

| Hispanic American | 8.0% | 4.8% | 16.3% |

| Native American | 1.1% | 1.5% | 0.7% |

| International student | 17.1% | N/A | N/A |

| Other/Unknown | 3.2% | 5.2% | 2.4% |

University of Washington had 47,571 total enrollments as of Autumn 2019, making it the largest university on the west coast by student population in spite of its selective admissions process.[102] It also boasts one of the most diverse student bodies within the US, with more than 50% of its undergraduate students self-identifying with minority groups.[103][104][105][106]

Organizations[]

Registered groups[]

The University of Washington boasts over 800 active Registered Student Organizations (RSOs), one of the largest networks of any universities in the world. RSOs are dedicated to a wide variety of interests both in and beyond campus. Some of these interest areas include academic focus groups, cultural exchanges, environmental activities, Greek life, political/social action, religious discussions, sports, international student gatherings by country, and STEM-specific events. Prominent examples are:

- The Dream Project: "The Dream Project teaches UW students to mentor first-generation and low-income students in King County high schools as they navigate the complex college admissions process."[107]

- The Rural Health Education (RHE): Promotes health in rural areas of Washington state through health fairs. Volunteers include students from a variety of backgrounds including medical, pharmacy, and dentistry. Health professionals from the Greater Seattle area also actively participate.

- Students Expressing Environmental Concern (SEED): partially funded by UW's Housing and Food Services (HFS) office to promote environmental sustainability, and reduce the university's carbon footprint.

- Student Philanthropy Education Program: Partnered with the UW's nonprofit, the UW Foundation, this group focuses on promoting awareness of philanthropy's importance through major events on campus.

- Husky Global Affairs: This is a club dedicated to social science research in global issues. It provides a forum for students to collaborate in research and publishes their research in the Global Affairs Journal.

- UW Delta Delta Sigma Pre-Dental Society (DDS): This is a club dedicated to serving pre-dental students and it provides a forum for discussion of dental-related topics.[108]

- UW Earth Club: The Earth Club is interested in promoting the expression of environmental attitudes and consciousness through specialized events.

- UW Farm: The UW farm grows crops on campus and advocates urban farming in the UW community.

- GlobeMed at UW: a student-run non-profit organization that works to educate about global poverty and its effect on health. The UW chapter is a part of a national network of chapters, each partnering with a grassroots organization at home or abroad. GlobeMed at UW is partnered with The MINDS Foundation which supports education about and treatment for mental illness in rural India.

- UW Sierra Student Coalition: SSC is dedicated to many larger environmental issues on campus and providing related opportunities to students.

- Washington Public Interest Research Group (WashPIRG): WashPIRG engages students in a variety of activist causes, including environmental projects on campus and the community.[109]

Student government[]

The Associated Students of the University of Washington (ASUW) is one of two Student Governments at the University of Washington, the other being the Graduate and Professional Student Senate. It is funded and supported by student fees, and provides services that directly and indirectly benefit them. The ASUW employs over 72 current University of Washington students, has over 500 volunteers, and spends $1.03 million annually to provide services and activities to the student body of 43,000 on-campus.[110] The Student Senate was established in 1994 as a division of the Associated Students of the University of Washington. Student Senate is one of two official student governed bodies and provides a broad-based discussion of issues. Currently, the ASUW Student Senate has a legislative body of over 150 senators representing a diverse set of interests on and off-campus.[111]

The ASUW was incorporated in the State of Washington on April 20, 1906.[112] On April 30, 1932, the ASUW assisted in the incorporation of University Book Store[113] which has been in continuous operation at the same location on University Way for over 70 years. The ASUW Experimental College, part of the ASUW, was created in 1968 by several University of Washington students seeking to provide the campus and surrounding community with a selection of classes not offered on the university curriculum.[114]

Publication[]

The student newspaper is The Daily of the University of Washington, usually referred to as The Daily. It is the second-largest[clarification needed] daily paper in Seattle. The Daily is published every day classes are in session during fall, winter and spring quarters, and weekly during summer quarters. In 2010, The Daily launched a half-hour weekly television magazine show, "The Daily's Double Shot," on UWTV Channel 27. The UW continues to use its proprietary UWTV channel, online and printed publications.[115] The faculty also produce their own publications for students and alumni.

Student Activism[]

Throughout the 20th Century, UW student activism centered around a variety of national and international concerns, from nuclear energy to the Vietnam War and civil rights. In 1948, at the beginning of the McCarthyism era, students brought their activism to bear on campus, by protesting the firing of three UW professors accused of communist affiliations.[116][117]

University support[]

UW offers many services for its students and alumni, beyond the standard offered by most colleges and universities. Its "Student Life" division houses 16 departments and offices that serve students directly and indirectly, including those below and overseen by Vice President and Vice Provost.

- Career Center

- Counseling Center

- Department of Recreational Sports (IMA)

- Disability Resource Center

- Fraternity and Sorority Life

- Health and Wellness Programs

- Housing and Food Services

- Office of Ceremonies

- Office of the University Registrar

- Student Admissions

- Student Activities and Union Facilities

- Student Financial Aid

- Student Legal Services

- Student Publications (The Daily)

- Campus Police[118]

Housing[]

The university operates one of the largest campuses of any higher education institution in the world. Despite this, growing faculty and student count has strained the regional housing supply as well as transportation facilities. Starting in 2012, UW began taking active measures to explore, plan and enact a series of campus policies to manage the annual growth. In addition to new buildings, parking and light rail stations, new building construction and renovations have been scheduled to take place through 2020.[119] The plan includes the construction of three six-story residence halls and two apartment complexes in the west section of campus, near the existing Terry and Lander Halls, in Phase I, the renovation of six existing residence halls in Phase II, and additional new construction in Phase III. The projects will result in a net gain of approximately 2,400 beds. The Residence Hall Student Association (student government for the halls) is the second-largest student organization on campus and helps plan fun events in the halls. For students, faculty, and staff looking to live off-campus, they may also explore Off-Campus Housing Affairs.[120]

The Greek System at UW has also been a prominent part of student culture for more than 115 years. It is made up of two organizational bodies, the Interfraternity Council (IFC) and the Panhellenic Association. The IFC looks over 34 fraternities with 1900+ members and Panhellenic consists of 19 sororities and 1900 members. The school has additional Greek organizations that do not offer housing and are primarily special interest.

Disability resources[]

In addition to the University of Washington's Disability Resources for Students (DRS) office, there is also a campus-wide DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology) Center program that assists educational institutions to fully integrate all students, including those with disabilities, into academic life. DO-IT includes a variety of initiatives, such as the DO-IT Scholars Program, and provides information on the 'universal' design of educational facilities for students of all levels of physical and mental ability.[121] These design programs aim to reduce systemic barriers which could otherwise hinder the performance of some students, and may also be applied to other professional organizations and conferences.[122]

Athletics[]

UW students, sports teams, and alumni are called Washington Huskies, and often referred to metonymically as "Montlake," due to the campus's location on Montlake Boulevard N.E.[123] (although the traditional bounds of the Montlake neighborhood do not extend north of the Montlake Cut to include the campus.) The husky was selected as the school mascot by the student committee in 1922, which replaced the "Sun Dodger", an abstract reference to the local weather.

The university participates in the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Division I-A, and the Pac-12 Conference. The football team is traditionally competitive, having won the 1960 and 1991 national title, to go along with eight Rose Bowl victories and an Orange Bowl title. From 1907 to 1917, Washington football teams were unbeaten in 64 consecutive games, an NCAA record.[124] Tailgating by boat has been a Husky Stadium tradition since 1920 when the stadium was first built on the shores of Lake Washington. The Apple Cup game is an annual game against cross-state rival Washington State University that was first contested in 1900 with UW leading the all-time series, 65 wins to 31 losses and 6 ties. College Football Hall of Fame member Don James is a former head coach.

The men's basketball team has been moderately successful, though recently the team has enjoyed a resurgence under coach Lorenzo Romar. With Romar as head coach, the team has been to six NCAA tournaments (2003–2004, 2004–2005, 2005–2006, 2008–2009, 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 seasons), 2 consecutive top 16 (sweet sixteen) appearances, and secured a No. 1 seed in 2005. On December 23, 2005, the men's basketball team won their 800th victory in Hec Edmundson Pavilion, the most wins for any NCAA team in its current arena.

Rowing is a longstanding tradition at the University of Washington dating back to 1901. The Washington men's crew gained international prominence by winning the gold medal at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, defeating the German and Italian crews much to the dismay of Adolf Hitler who was in attendance.[125] In 1958, the men's crew deepened their legend with a shocking win over Leningrad Trud's world champion rowers at the Moscow Cup, resulting in the first American sporting victory on Soviet soil,[126][127] and certainly the first time a Russian crowd gave any American team a standing ovation during the Cold War.[128] The men's crew have won 46 national titles[129] (15 Intercollegiate Rowing Association, 1 National Collegiate Rowing Championship), 15 Olympic gold medals, two silver and five bronze. The women have 10 national titles and two Olympic gold medals. In 1997, the women's team won the NCAA championship.[129] The Husky men are the 2015 national champions.

Recent national champions include the softball team (2009), the men's rowing team (2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2009, 2007), NCAA Division I women's cross country team (2008), and the women's volleyball team (2005). Individually, Scott Roth was the 2011 NCAA men's Outdoor Pole Vault and 2011 & 2010 NCAA men's Indoor Pole Vault champion. James Lepp was the 2005 NCAA men's golf champion. Ryan Brown (men's 800 meters) and Amy Lia (women's 1500 meters) won individual titles at the 2006 NCAA Track and Field Championships. Brad Walker was the 2005 NCAA men's Outdoor and Indoor Pole Vault champion.

The university has an extensive series of sports facilities, including but not limited to the Husky Stadium (football, track and field), the Alaska Airlines Arena at Hec Edmundson Pavilion (basketball, volleyball, and gymnastics), Husky Ballpark (baseball), Husky Softball Stadium, The Bill Quillian Tennis Stadium, The Nordstrom Tennis Center, Dempsey Indoor (Indoor track and field, football) and the Conibear Shellhouse (rowing). The golf team plays at the Washington National Golf Club and until recently, the swimming team called the Weyerhaeuser Aquatic Center and the Husky pool home. The university discontinued its men's and women's swim teams on May 1, 2009, due to budget cuts.[130]

Husky Stadium[]

The rebuilt Husky Stadium is the first and primary source of income for the completely remodeled athletic district. The major remodel consisted of a new grand concourse, underground light-rail station which opened on March 19, 2016,[131] an enclosed west end design, replacement of bleachers with individual seating, removal of track and Huskytron, as well as the installation of a new press box section, private box seating, football offices, permanent seating in the east end zone that does not block the view of Lake Washington. The project also included new and improved amenities, concession stands, and bathrooms throughout. The cost for renovating the stadium was around $280 million and was designed for a slightly lower seating capacity than its previous design, now at 70,138 seats.

Besides hosting national and regional football games, the Husky Stadium is also used by the university for its annual Commencement event, departmental ceremonies, and other events. Husky Stadium is one of several places that may have been the birthplace of the crowd phenomenon known as "The Wave". It is claimed that the wave was invented by Husky graduate Robb Weller and UW band director Bill Bissel in October 1981, for an afternoon game facing opponents from Stanford University.

Mascot[]

The University of Washington's costumed mascot is Harry the Husky. "Harry the Husky" performs at sporting and special events, and a live Alaskan Malamute, currently named Dubs II,[132] has traditionally led the UW football team onto the field at the start of games. The school colors of purple and gold were adopted in 1892 by student vote. The choice was inspired by the first stanza of Lord Byron's The Destruction of Sennacherib:[133][134]

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold,

And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;

And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea,

When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee.

Additionally, the university has also hosted a long line of Alaskan Malamutes as mascots.[135]

School songs[]

The University of Washington Husky Marching Band performs at many Husky sporting events including all football games. The band was founded in 1929, and today it is a cornerstone of Husky spirit. The band marches using a traditional high step, and it is one of only a few marching bands left in the United States to do so. Like many college bands, the Husky band has several traditional songs that it has played for decades, including the official fight songs "Bow Down to Washington" and "Tequila", as well as fan-favorite "Africano".

Notable alumni and faculty[]

Michael P. Anderson, NASA Astronaut and Space Shuttle Columbia disaster crew member

Pappy Boyington, World War II combat fighter ace

Dale Chihuly, glass sculptor

Kenny G, Grammy Award-winning jazz musician

Tom Foley, 49th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

Jay Inslee, 23rd Governor of Washington

Sally Jewell, 51st United States Secretary of the Interior and former CEO of REI

Bruce Lee, actor and martial artist

Kyle MacLachlan, Golden Globe Award-winning actor

Joel McHale, actor and comedian

Warren Moon, Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback

Jim L. Mora, former NFL coach

Brandon Roy, former NBA Rookie of the Year

Hope Solo, former USWNT goalkeeper

Isaiah Thomas, two-time NBA All-Star

Rainn Wilson, actor

Notable alumni of the University of Washington include U.S. Olympic rower Joe Rantz (1936); architect Minoru Yamasaki (1934); news anchor and Big Sky resort founder Chet Huntley (1934); US Senator Henry M. Jackson (JD 1935); Baskin Robbins co-founder Irv Robbins (1939); former actor, The Hollywood Reporter columnist and TCM host Robert Osborne (1954); glass artist Dale Chihuly (BA 1965); serial killer Ted Bundy; Nobel Prize-winning biologist Linda B. Buck; Pulitzer Prize-winning author Marilynne Robinson (PhD 1977), martial artist Bruce Lee; saxophonist Kenny G (1978); MySpace co-founder Chris DeWolfe (1988); Mudhoney lead vocalist Mark Arm (1985, English);[136] Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil (Philosophy);[137] music manager Susan Silver (Chinese);[138] actor Rainn Wilson (BA, Drama 1986); radio and TV personality Andrew Harms (2001, Business and Drama); actor and comedian Joel McHale (1995, MFA 2000), actor and Christian personality Jim Caviezel and basketball player Matisse Thybulle.

In film[]

- 1965: The Slender Thread, directed by Sydney Pollack

- 1979: The Changeling, directed by Peter Medak[139]

- 1983: WarGames, directed by John Badham[140]

- 1987: Black Widow, directed by Bob Rafelson[141]

- 1992: Singles, directed by Cameron Crowe[142]

- 1997: The Sixth Man, directed by Randall Miller[143]

- 1999: 10 Things I Hate About You, directed by Gil Junger[144]

- 2004: What the Bleep Do We Know: Down the Rabbit Hole, directed by William Arntz[145]

- 2007: Dan in Real Life, directed by Peter Hedges[146]

- 2013: 21 and Over, directed by Jon Lucas[147]

- 2016: The Boys of 36, directed by Margaret Grossi

See also[]

- Friday Harbor Laboratories

- Internationales Kulturinstitut

- List of forestry universities and colleges

- Manastash Ridge Observatory

- Theodor Jacobsen Observatory

- University Book Store

- University of Washington Educational Outreach

- University of Washington firebombing incident

- Washington Escarpment – escarpment in Antarctica named for the university

References[]

- ^ Buhain, Venice (May 25, 1999). "But what does it mean?". The Daily. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ As of June 30, 2020. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2020 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY19 to FY20 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. February 19, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "Apply - Interfolio".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Fast Facts 2019" (PDF). University of Washington. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Colors". Washington.edu. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ "Dub" being a phonetic shorthand for "W" ("double-you").

- ^ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Center for Postsecondary Education. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Entering a Golden Age of Innovation in Computer Science". March 9, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Olympians – Washington Rowing". Washington Rowing. Archived from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Banel, Feliks (October 8, 2012). "Founding The University Of Washington, One Student At A Time". KUOW.org. KUOW-FM. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Speidel, William (1967). Sons of the Profits. Seattle: Nettle Creek Publishing Company. pp. 81–103.

- ^ Bhatt, Sanjay (October 3, 2013), "UW has big plans for its prime downtown Seattle real estate", The Seattle Times, archived from the original on October 5, 2013, retrieved October 6, 2013

- ^ "CHS Re:Take – Pike's place on Capitol Hill". January 15, 2017. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ "The University of Washington's Early Years". No Finer Site: The University of Washington's Early Years On Union Bay. University Libraries. University of Washington. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ "University of Washington". Great Depression in Washington State Project. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ "Phase II — A Place for Some of Our Best Students". Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "The Black Student Union at UW: Black Power on Campus". Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ Kindig, Jesse. "Student Activism at UW, 1948–1970". Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ "UW Police Department: History". Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ "Top Colleges in Tech | Paysa Blog". www.paysa.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ Hess, Abigail (July 26, 2017). "Here's how much education you need to work at top tech companies". Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "About the Gates family | Give to the UW". www.washington.edu. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ "University Link light-rail service starts March 19". The Seattle Times. January 26, 2016. Archived from the original on July 13, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Keeley, Sean (March 17, 2016). "UW & Capitol Hill Light Rail Stations Are Ready". Curbed Seattle. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Lyttle, Bethany. "University of Washington, Seattle, Wash. – pg.5". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Housing Master Plan – UW HFS". hfs.uw.edu. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Long, Katherine (October 10, 2014). "UW plan to raze old dorms, raise rents in new ones worries students". seattletimes.com. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Burke Museum team discovers a T. rex". Burke Museum. August 17, 2016. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Researchers excavate T. rex skull at UW's Burke Museum". KING. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "As visitors watch, Burke Museum preps its T. rex exhibit". Spokesman.com. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Our Back Pages: The UW Golf Course". www.washington.edu. Archived from the original on July 24, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ "Office of the President". www.washington.edu. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "UW Regents approve contract for President Ana Mari Cauce". UW News. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Regents: Two-time university president expected to serve at helm of Texas A&M". theeagle.com. February 3, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ "Biography – Phyllis Wise". University of Illinois. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "2017 Bondholder Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2018.

- ^ University of Washington Investment Management Company. "University of Washington Quarterly Investment Performance Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2018.

- ^ "New UW payroll system behind schedule, more costly than expected". The Seattle Times. November 26, 2015. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "UW has $1 billion in buildings going up or planned in Seattle". The Seattle Times. April 29, 2018. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Mayor Announces UW Green Energy Purchase". City of Seattle. February 2006. Archived from the original on January 16, 2007. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ "Who's Who". American College & University. Presidentsclimatecommitment.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ Roseth, Robert (February 5, 2009). "UW seeks to deepen its commitment to sustainability". Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ "About the Environmental Stewardship Advisory Committee (ESAC)" (PDF). Environmental Stewardship Advisory Committee. August 10, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ "Environmental Stewardship Advisory Committee". University of Washington. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Housing and Food Services: Environmental Stewardship and Sustainability". University of Washington. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010.

- ^ "College Sustainability Report Card 2008". Sustainable Endowments Institute. Archived from the original on July 17, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "UW again receives grade of A- for sustainability". September 26, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ "Academic Departments". University of Washington. Archived from the original on January 24, 2010. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ "The Halbert and Nancy Robinson Center for Young Scholars". Archived from the original on July 21, 2009. Retrieved May 24, 2009.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020: National/Regional Rank". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2019". Forbes. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- ^ "Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings 2021". The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "2021 Best National University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "2020 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2022". Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2021". Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ "2021 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "University of Washington – U.S. News Best Grad School Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "University of Washington – U.S. News Best Global University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ Greene, Howard; Greene, Matthew W. (2001). Public Ivies. Greenes' Guide to Educational Planning. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-093459-0.

- ^ "Association of American Universities". Archived from the original on August 10, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ "Faculty & Staff, University of Washington". 2012. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2001.

- ^ University of Washington. "Faculty Memberships and Awards". Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ Trujillo, Joshua (May 7, 2010). "Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden honors local Nobel Laureates". The Seattle Post Intelligencer. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ "Future Students, University of Washington". 2012. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- ^ "University of Washington is a top producer of Fulbright scholars Students". 2018. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities——University of Washington". Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings 2016". Times Higher Education. July 2019. Archived from the original on September 19, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ "University of Washington – QS Ranking". Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "University of Washington Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "SCImago Institutions Rankings – Higher Education – All Regions and Countries – 2019 – Overall Rank". www.scimagoir.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ Cairns, Eva. "University Rankings: How Important Are They?". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ "Leiden Ranking 2017 by Leiden University". Leidenranking.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "College Finder". Kiplinger's Personal Finance. July 2019.

- ^ "2018 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. May 11, 2019. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ "The Princeton Review's College Ratings | The Princeton Review". www.princetonreview.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "University of Washington – The Princeton Review College Rankings & Reviews". www.princetonreview.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "University of Washington". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Freshmen by the numbers". Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "University of Washington Quick Facts". University of Washington. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012.

- ^ "UW Fast Facts: 2017" (PDF). University of Washington – Office of Planning and Budgeting. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ "Capacity-constrained majors". Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Applying for a capacity-constrained major?". Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "UW Undergraduate Advising: Majors and Minors". Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Exploring Major Alternatives, retrieved January 29, 2021

- ^ "University of Washington Annual Report 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Top American Research Universities (December 2005)". Mup.asu.edu. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "UW passed $1 billion research budget mark". Uwnews.washington.edu. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ As of June 30, 2016. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2015 to FY 2016" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2017.

- ^ University of Washington (2008), Annual Report Of Awards And Expenditures Related To Research, Training, Fellowships, and Other Sponsored Programs (PDF), University of Washington, archived from the original (PDF) on November 3, 2013

- ^ Jaschik, Scott (October 13, 2006). "Inside HigherEd Husky Promise". Insidehighered.com. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "UW Husky Promise". Depts.washington.edu. October 11, 2006. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Education News - College Admissions, MBA Programs, Financial Aid - Wsj.com". Collegejournal.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "ResearchChannel contact UW". Archived from the original on June 21, 2006.

- ^ "ResearchChannel participants". Archived from the original on August 29, 2006.

- ^ "About", Pacific Coast Architecture Database, University of Washington

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sekine, Sara (March 6, 2019). "Chinese hackers target North American and Asian universities". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ "University of Washington Quick Stats" (PDF). UW Office of the Registrar. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 12, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ See Washington (state)#Demographics and Demographics of the United States for references.

- ^ "Office of Admissions. University of Washington". Admit.washington.edu. May 1, 2012. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Undergraduates." Office of News and Information. University of Washington. Archived September 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shelley, Anthony (April 24, 2007). "UW admissions more competitive". The Daily of the University of Washington. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Common Data Set".

- ^ "Freshmen by the numbers | Office of Admissions".

- ^ "UW Dream Project | Supporting Seattle-area high school students through the college admissions process". Washington.edu. June 28, 2013. Archived from the original on February 18, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "DDS". Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ "Student Organizations". Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ "Associated Students of the University of Washington | SAF | Services and Activities Fee". depts.washington.edu. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ "History". senate.asuw.org. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ "Corporations Division". Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ "Corporations Division". Washington Secretary of State. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ "Experimental College". Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ "UWTV". UWTV. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ Kindig, Jessie. "Student Activism at UW, 1948–1970". UW Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium. Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ McBride, Devon (March 11, 2019). "The long history of activism at the UW". The Daily. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "UW Police". Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ "Campus Master Plan | Capital Planning and Development". cpd.uw.edu. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ "Off-Campus Housing Affairs". ASUW. Archived from the original on December 15, 2004.

- ^ "Universal Design: Process, Principles, and Applications". Washington.edu. June 14, 2012. Archived from the original on April 28, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Applications of Universal Design to Projects, Conference Exhibits, Presentations, and Professional Organizations". Washington.edu. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ Thiel, Art (January 21, 2007). "Mora's move generates intrigue". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ "2014 NCAA Football Record Book" (PDF). NCAA. p. 117. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Raley, Dan (December 21, 1999). "Events of the century". Seattle Post Intelligencer. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ Johns, Greg (August 23, 2007). "Huskies crew earns return trip to Moscow". Seattle PI. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Thiel, Art (September 4, 2007). "UW crew gets front seat to history". Seattle PI. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Water World Archived September 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Sports Illustrated, November 17, 2003.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Raley, Dan (April 30, 2003). "Crew: UW's most successful, stable athletic enterprise". Seattle PI. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Condotta, Bob (May 2, 2009). "Huskies | UW cuts swimming teams | Seattle Times Newspaper". Seattletimes.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "University Link light-rail service starts March 19". The Seattle Times. January 26, 2016. Archived from the original on July 13, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Webeck, Evan (March 23, 2018). "10/10, would cheer with: UW introduces new live mascot, Dubs II, and he is adorable". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "School Colors: Purple and Gold". CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on December 10, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "University Chronology". University of Washington. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "Washington Huskies". Washington Huskies. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Moriarity, Sean (November 2, 1999). "Mark Arm Speaks!". The University of Washington Daily. Archived from the original on October 4, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Neely, Kim (July 9, 1992). "Soundgarden: Rock's Heavy Alternative". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Kim, Jae-Ha (April 27, 1997). "Susan Silver steers careers toward rock stardom". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2004. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "The Changeling (1980)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2013. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Filming Locations for WarGames". International Movie Database. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ >"Filming Locations for Black Widow". International Movie Database. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (September 18, 1992). "Singles (1992) Review/Film; Youth, Love and a Place of One's Own". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 28, 1997). "The Sixth Man (1997) Hoop Dreams and (Ghostly) Schemes". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (March 31, 1999). "10 Things I Hate About You (1999) FILM REVIEW; It's Like, You Know, Sonnets And Stuff". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Movie – What the Bleep!? Down the Rabbit Hole (2006)". Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (October 26, 2007). "A Family Just Like Yours (if You Lived in a Movie)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2010. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Movie filming on University of Washington campus". King 5 News. August 29, 2011. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to University of Washington. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about "University of Washington". |

- Official website

- University of Washington Athletics website

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Calvin F. Todd Photographs Collection includes images from 1905 to 1930 of the University of Washington campus and scenes from Seattle including the waterfront, various buildings especially apartments, regrading activities, and the Pike Place Market.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – University of Washington Campus Photographs Photographs reflecting the early history of the University of Washington campus from its beginnings as the Territorial University through its establishment at its present site on the shores of Lake Washington. The database documents student activities, buildings, departments, and athletics.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- University of Washington

- Educational institutions established in 1861

- Flagship universities in the United States

- Research institutes in Seattle

- Universities and colleges accredited by the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities

- Universities and colleges in Seattle

- Public universities and colleges in Washington (state)

- 1861 establishments in Washington Territory