Upland moa

| Upland moa Temporal range: Pleistocene-Holocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton | |

Extinct (ca. 1500)

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Clade: | Notopalaeognathae |

| Order: | †Dinornithiformes |

| Family: | †Megalapterygidae Bunce et al., 2009 |

| Genus: | †Megalapteryx Haast 1886[1] |

| Species: | †M. didinus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Megalapteryx didinus | |

| Synonyms | |

|

list

| |

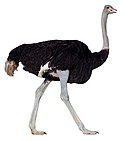

The upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus) was a species of moa endemic to New Zealand. It was a member of the ratite family, a type of flightless bird with no keel on the sternum. It was the last moa species to become extinct, vanishing around 1500 CE, and was predominantly found in alpine and sub-alpine environments.

Taxonomy[]

In 2005, a genetic study suggested that M. benhami, which had previously been considered a junior synonym of M. didinus, may have been a valid species after all.[3]

The cladogram below follows a 2009 analysis by Bunce et al.:[4]

| Dinornithiformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description[]

At less than 1 metre tall and about 17 to 34 kilograms, the upland moa was among the smallest of the moa species. Unlike other moas, it had feathers covering all of its body but the beak and the soles of its feet, an adaptation to its cold environment.[5] Scientists believed in the past that the upland moa held its neck and head upright; however, it actually carried itself in a stooped posture with its head level to its back. This would have helped it travel through the abundant vegetation in its habitat, whereas an extended neck would have been more suited to open spaces.[6] It had no wings or tail.[7]

Distribution and habitat[]

The upland moa lived only on New Zealand's South Island, in mountains and sub-alpine regions. They travelled to elevations as high as 2000 m (7000 ft).[6]

Behavior and ecology[]

The upland moa was herbivorous, its diet extrapolated from fossilised stomach contents, droppings, and the structure of its beak and crop. It ate leaves and small twigs, using its beak to "shear[…]with scissor-like moves".[6] Its food required grinding before it could be digested, as indicated by its large crop.[6] A 2004 study of the upland moa's coprolite provided evidence that branchlets of trees such as Nothofagus, various lake-edge herbs, and tussock made up part of its diet.[8] This moa usually laid only 1 to 2 blue-green coloured eggs at once,[6][9] and was likely the only type of moa to lay eggs that were not white in colour.[10] Like the emu and ostrich, male moa cared for the young.[5] The upland moa's only predator before the arrival of humans in New Zealand was the Haast's eagle.[6]

Extinction[]

Humans first came in contact with the upland moa around 1250 to 1300 AD, when the Māori people arrived in New Zealand from Polynesia. Moa, a docile animal, were an easy source of food for the Māori and were eventually hunted to extinction in 1500.[6][11]

Discoveries[]

Several specimens with soft tissue and feather remains are known:

- British Museum A16, found at Queenstown in 1876, is the type of the species.

- Otago Museum C.68.2A, leg with much muscle tissue, skin and feathers from the

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa NMNZ S.000400, a skeleton with tissue on neck and head from the Cromwell area.[12]

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa NMNZ S.023080, a foot with some muscle and sinews, found on 7 January 1987 at Mount Owen. This was dated to be about 3,300–3,400 years old.[13]

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa NMNZ S.027950, feathers found in 1949 at , Fiordland, New Zealand.[14]

- Canterbury Museum NZ 1725, Remains of one partial egg which have been found at the Rakaia River in 1971 are tentatively attributed to this species. The radiocarbon date of approximately AD 1300–1400 is in line with this. Unusually, the eggshell is dark olive green, but even if the egg is of M. didinus, the shell colour may have varied between individual eggs.[15]

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa NMNZ S.023700, complete skeleton found by Trevor Worthy in March 1987 at Honeycomb Hill Cave, Oparara Valley[16]

- Otago Museum AV10049, skeleton and partial egg found in 2002 at Serpentine Range, Humboldt Mountains.[17]

Footnotes[]

- ^ a b Brands, S. (2008)

- ^ Checklist Committee Ornithological Society of New Zealand (2010). "Checklist-of-Birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands and the Ross Dependency Antarctica" (PDF). Te Papa Press. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Baker, A. J.; Huynen, L. J.; Haddrath, O.; Millar, C. D.; Lambert, D. M. (2005). "Reconstructing the tempo and mode of evolution in an extinct clade of birds with ancient DNA: The giant moas of New Zealand". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (23): 8257–62. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.8257B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409435102. PMC 1149408. PMID 15928096.

- ^ Bunce, M.; Worthy, T. H.; Phillips, M. J.; Holdaway, R. N.; Willerslev, E.; Haile, J.; Shapiro, B.; Scofield, R. P.; Drummond, A.; Kamp, P. J. J.; Cooper, A. (2009). "The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (49): 20646–20651. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620646B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906660106. PMC 2791642. PMID 19923428.

- ^ a b Flannery, Tim, "A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World's Extinct Animals", October 2001, "[1]"

- ^ a b c d e f g Museum of New Zealand, "Upland Moa", 1998, http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/theme.aspx?irn=1348

- ^ TerraNature, "Flightless Birds: Moa", http://terranature.org/moa.htm

- ^ Mark Horrocks, et. al, "Plant remains in coprolites: diet of a subalpine moa (Dinornithiformes) from southern New Zealand", Emu Austral Ornithology, 2004 http://www.publish.csiro.au/paper/MU03019.htm

- ^ Igic, Branislav; et al. (2010). "Detecting pigments from colorful eggshells of extinct birds". Chemoecology. 20 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1007/s00049-009-0038-2. S2CID 10956718.

- ^ Gill, B.J. (2006). "A CATALOGUE OF MOA EGGS (AVES: DINORNITHIFORMES)". Records of the Auckland Museum. 43: 55–80. ISSN 1174-9202.

- ^ Worthy, Trevor H.'Moa – Moa and people', Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 13-Jul-12 URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/moa/page-4

- ^ Museum of New Zealand(a)

- ^ Worthy, T. H. (1989)

- ^ Museum of New Zealand(b)

- ^ McCulloch, B. (1991)

- ^ Museum of New Zealand(c)

- ^ "THE HUNT IS ON: Upland Moa Recovery Project".

References[]

- Brands, Sheila J. (1989). "The Taxonomicon". Zwaag, Netherlands: Universal Taxonomic Services. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003). "Moas". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2 ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 95–98. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- McCulloch, Beverley (1992). "Unique, dark olive-green moa eggshell from Redcliffe Hill, Rakaia Gorge, Canterbury" (PDF). Notornis. 39 (1): 63–65. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2006.

- Museum of New Zealand(a). "Megalapteryx didinus". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Museum of New Zealand(b). "Megalapteryx didinus". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Museum of New Zealand(c). "Megalapteryx didinus". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Worthy, Trevor H. (1989). "Mummified moa remains from Mt Owen, northwest Nelson" (PDF). Notornis. 36 (1): 36–38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2006.

External links[]

Media related to Megalapteryx didinus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Megalapteryx didinus at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Megalapteryx didinus at Wikispecies

Data related to Megalapteryx didinus at Wikispecies- Upland Moa. Megalapteryx didinus. by Paul Martinson. Artwork produced for the book Extinct Birds of New Zealand by Alan Tennyson, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2006

- Articulated skeleton at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Articulated Upland moa skeleton at the Otago Museum

- Megalapteryx

- Birds of the South Island

- Extinct flightless birds

- Extinct birds of New Zealand

- Bird extinctions since 1500

- Late Quaternary prehistoric birds

- Ratites

- Birds described in 1883

- Species made extinct by human activities