Vatican and Eastern Europe (1846–1958)

The Vatican and Eastern Europe (1846–1958) describes the relations from the pontificate of Pope Pius IX (1846–1878) through the pontificate of Pope Pius XII (1939–1958). It includes the relations of the Church State (1846–1870) and the Vatican (1870–1958) with Russia (1846–1918), Lithuania (1922–1958) and Poland (1918–1958).

Pope Pius IX : protest or silence[]

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

The Pontificate of Pius IX began in 1846. In 1847 an Accomodamento, a generous agreement, by which Russia allowed the Pope to fill vacant Episcopal Sees of the Latin rites both in Russia and the Polish and Lithuanian provinces of Russia. The new freedoms were short-lived, as they were undermined by jealousies of the rival Orthodox Church, Polish political aspirations, and the tendency of imperial Russia to act most brutally against any dissension. Pius IX first tried to position himself in the middle, strongly opposing revolutionary and violent opposition against the Russian authorities and appealing to them for more Church freedom. After the failure of the 1863 Polish uprising, he sided with the persecuted Poles, loudly protesting their persecutions, infuriating the Tsarist government to the point that all Catholic seats were closed by 1870, a catastrophe that continued to haunt Vatican diplomacy for decades to come.[1]

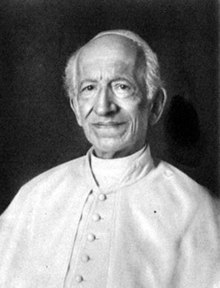

Diplomacy of Pope Leo XIII[]

Russia[]

Pope Leo XIII began his pontificate with a friendly letter to Tsar Alexander II in which he reminded the Russian monarch of the millions of Catholics living in his empire, who would like to be good Russian subjects, provided their dignity is respected.

Poland[]

In Prussia, Polish Catholics were persecuted as Poles and, during the Kulturkampf, as Catholics as well. Otto von Bismarck began in 1871, insinuated a Polish-Catholic-Austrian connection.[2]

Pius X : broken Russian promises[]

Russia[]

Under Pope Pius X (1903–1914), the situation of Polish Catholics in Russia did not improve.

Poland[]

By 1914, Germany needed Polish volunteers for the war. Polish politicians had modest requests for their support: full recognition of Polish, religious education in Polish, the return of expropriated properties and the elimination of laws that discriminated against the Polish population.[3] They were not granted.

Pope Benedict XV[]

Russia and the Soviet Union[]

With the Russian Revolution, the Vatican was faced with a new, so far unknown situation, an ideology and a government that rejected not only the Catholic Church but also religion as a whole. “The Pope, the Tsar, Metternich, French radicals and German police" were against it according to the 1848 Communist Manifesto. The Historical Institute of the Soviet Academy of Sciences wrote that "reactionary policies of the Vatican" were an outgrow of fear of socialism and hate of communism.

Baltic states[]

The relations with Russia changed drastically for a second reason. The Baltic states and Poland gained their independence from Russia after World War I, thus enabling a relatively free church life in those former Russian countries. Estonia was the first country to look for Vatican ties. On 11 April 1919, Secretary of State Pietro Gasparri informed the Estonian authorities that the Vatican would agree to have diplomatic relations. A concordat was agreed upon in principle a year later, in June 1920. Because of the small Catholic population in predominantly Protestant Estonia, the handful of Catholic priests there continued to be administered from Latvia until 1924. Development of an independent Catholic hierarchy for Estonia began late in that year with the formation of the Apostolic Administration of Estonia in November.[4]

Jāzeps Rancāns became the first representative of the fledgling Latvian government at the Vatican in October 1919.[5] Hermanis Albats negotiated a concordat between Latvia and the Holy See in May 1921.[5] The concordat of 1922 was signed 30 May 1922. It guaranteed freedom for the Catholic Church, established an archdiocese, liberated clergy from military service, allows the creation of seminaries and catholic schools and described church property rights and immunity. The Archbishop swore alliance to Latvia.[6]

Relations with Catholic Lithuania were slightly more complicated because of the Polish occupation of Vilnius, a city and archiepiscopal seat, which Lithuania claimed as well as its own. Polish forces had occupied Vilnius and committed acts of brutality in its Catholic seminary there, which generated several protests of Lithuania to the Holy See.[7] Relations with the Holy See were defined during the pontificate of Pope Pius XI (1922–1939).

Poland[]

Before all other heads of state, Pope Benedict XV in October 1918 congratulated the Polish people to their independence.[8] In a public letter to the archbishop Kakowski of Warsaw, he remembered their loyalty and the many efforts of the Holy See to assist them. He expressed his hopes that Poland will take again its place in the family of nations and continue its history as an educated Christian nation.[8] In March 1919, he nominated ten new bishops and, soon afterward, Achille Ratti, already in Warsaw as his representative, as papal nuncio.[8]

Pope Pius XI[]

Negotiations with the Soviet Union[]

Pius XI nominated Michel d'Herbigny in 1922 as his principal agent in policymaking towards the Soviet Union. In Berlin, Nuncio Eugenio Pacelli worked mainly on clarifying the relations between Church and the German State. After Achille Ratti was elected Pope, in the absence of a papal nuncio in Moscow, Pacelli worked also on diplomatic arrangements between the Vatican and the Soviet Union. He negotiated food shipments for Russia, where the Church was persecuted. He met with Soviet representatives including Foreign Minister Georgi Chicherin, who rejected any kind of religious education, the ordination of priests and bishops, offering only agreements without the points vital to the Vatican.[9] "An enormously sophisticated conversation between two highly intelligent men like Pacelli and Chicherin, who seemed not to dislike each other," wrote one participant.[10] Despite Vatican pessimism and a lack of visible progress, Pacelli continued the secret negotiations until Pope Pius XI ordered them to be discontinued in 1927.

The "harsh persecution short of total annihilation of the clergy, monks, and nuns and other people associated with the Church" [11] continued well into the Thirties. In addition to executing and exiling many clerics, monks and laymen, the confiscating of Church implements "for victims of famine" and the closing of churches were common.[12] Yet according to an official report based on the Census of 1936, some 55% of Soviet citizens identified themselves openly as religious, others possibly concealing their belief.[12]

Poland[]

During the pontificate of Pope Pius XI (1922–1939), Church life in Poland flourished: There were some anti-clerical groups opposing the new role of the Church especially in education,[13] But numerous religious meetings and congresses, feasts and pilgrimages, many of which were accompanied by supportive letters from the Pontiff, took place.[13]

Lithuania [14][]

Lithuania was recognized by the Vatican in November 1922. The recognition included a stipulation by Pietro Gasparri to Lithuania, “to have friendly relations with Poland”. There were diplomatic stand-stills, as the Lithuanian government refused to accept virtually all episcopal appointments by the Vatican. The relations did not improve when, in April 1926 Pope Pius XI unilaterally established and reorganized Lithuanian ecclesiastical province without regard to Lithuanian demands and proposals, the real bone of contention being Vilnius, occupied by Poland. In the Fall of 1925, Mečislovas Reinys, a Catholic professor of Theology became Lithuanian Foreign Minister, and asked for an agreement. The Lithuanian military took over a year later, and a proposal of a concordat, drafted by the papal visitator Jurgis Matulaitis-Matulevičius, was agreed upon by the end of 1926. This concordat was signed in Rome on 27 September 1927 by Cardinal Gasparri and Augustinas Voldemaras.[15] Its content follows largely the Polish Concordat of 1925. Ratifications were exchanged at the Vatican on 10 December 1927 by Cardinal Gasparri and Jurgis Šaulys.[16]

Pope Pius XII[]

Russia[]

Poland[]

See also[]

- Persecutions of the Catholic Church and Pius XII

- Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

- Persecution of Christians in Warsaw Pact countries

- Reorganization of dioceses during World War II

- Diplomacy of the Holy See

References[]

- Toomas Abiline and Indrek Oper, St Peter and St Paul's Cathedral in Tallinn, The Apostolic Administration of Estonia, Tallinn, 2006?

- Acta Sanctae Sedis, (ASS), Romae, Vaticano 1865

- Acta Apostolicae Sedis (AAS), Romae, Vaticano 1922-1960

- Acta et decreta Pii IX, Pontificis Maximi, VolI-VII, Romae 1854 ff

- Acta et decreta Leonis XIII, P.M. Vol I-XXII, Romae, 1881, ff

- Owen Chadwick, The Christian Church in the Cold War, London 1993

- Jesse D. Clarkson, A history of Russia, Random House, New York, 1969

- Richard cardinal Cushing, Pope Pius XII, St. Paul Editions, Boston, 1959

- Victor Dammertz O.S.B., Ordensgemeinschaften und Säkularinstitute, in Handbuch der Kirchengeschichte, VII, Herder Freiburg, 1979, 355-380

- Matthias Erzberger, Erlebnisse im weltkrieg, Stuttgart, 1920

- Alexis Ulysses Floridi S.J., Moscow and the Vatican, Ardis Publishers, Ann Arbor-MI, 1986 ISBN 0-88233-647-9

- A. Galter, Rotbuch der verfolgten Kirchen, Paulus Verlag, Recklinghausen, 1957

- Alberto Giovanetti, Pio XII parla alla Chiesa del Silenzio, Editrice Ancona, Milano, 1959, German translation, Der Papst spricht zur Kirche des Schweigens, Paulus Verlag, Recklinghausen, 1959

- Herder Korrespondenz Orbis Catholicus, Freiburg, 1946–1961

- Andrey Micewski, Cardinal Wyszynski, A biography, Harcourt, New York, 1984

- Pio XII, Discorsi e Radiomessagi, Roma Vaticano, 1939–1959

- Jāzeps Rancāns, My memories of Professor Hermanis Albats, Universitas, 3 (1956), pp. 25–26 (in Latvian)

- Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, A History of Russia, Oxford University Press, New York, 1963

- Josef Schmidlin Papstgeschichte, Vol I-IV, Köstel-Pusztet München, 1922–1939

- Jan Olav Smit, Pope Pius XII, London Burns Oates & Washbourne LTD,1951

- Hansjakob Stehle, Die Ostpolitik des Vatikans, Piper, 1975

Sources[]

- ^ All sources if not otherwise quoted, are Schmidlin, II, pp. 213-224

- ^ Micewski 3

- ^ Erzberger, 173

- ^ Abiline and Oper, p. 10

- ^ a b Rancāns, p. 25

- ^ Schmidlin III, 305

- ^ Schmidlin III, 306.

- ^ a b c Schmidlin III, 306

- ^ Hansjakob Stehle, Die Ostpolitik des Vatikans, Piper, München, 1975, p.139-141

- ^ Hansjakob Stehle, Die Ostpolitik des Vatikans, Piper, München, 1975, p.132

- ^ Riasanovsky 617

- ^ a b Riasanovsky 634

- ^ a b Schmidlin IV, 135

- ^ Schmidlin, Papal History, IV, 138 ff

- ^ Conventio eum Rep. Lithuaniae, Acta Apostolicae Sedis, Volume 19 (1927), p. 433

- ^ Conventio eum Rep. Lithuaniae, Acta Apostolicae Sedis, Volume 19 (1927), p. 434

- Catholic Church in Europe

- Second Polish Republic

- History of the papacy