Vebjørn Sand Da Vinci Project

da Vinci Bridge da Vinci-Broen | |

|---|---|

The da Vinci bridge in Ås | |

| Coordinates | 59°43′08″N 10°47′03″E / 59.718872°N 10.784276°ECoordinates: 59°43′08″N 10°47′03″E / 59.718872°N 10.784276°E |

| Carries | pedestrian and bicycle traffic |

| Crosses | Highway E-18 |

| Locale | Nygård, Ås, Akershus Norway |

| Named for | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Owner | Norwegian Public Roads Administration |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Deck arch bridge |

| Material | Laminated wood; steel-reinforced |

| Total length | 109 m (358 ft) |

| Longest span | 40 m (130 ft) |

| History | |

| Architect | Vebjørn Sand Selberg Architects |

| Designer | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Engineering design by | Reinhert Structural Engineers |

| Construction start | 1997 |

| Construction end | 2001 |

| Construction cost | 12 million Norwegian kroner |

| Opened | 2001 |

| Location | |

| |

The Vebjørn Sand da Vinci Project built a laminated-wood parabolic-arch pedestrian bridge in Norway over European route E18 in Ås, Norway, in 2001. It was a partnership between the Norwegian Public Roads Administration and Norwegian painter and artist Vebjørn Sand, who headed the project. The resulting da Vinci Bridge is one of several installations that Sand is known for in Norway.

History[]

Original design[]

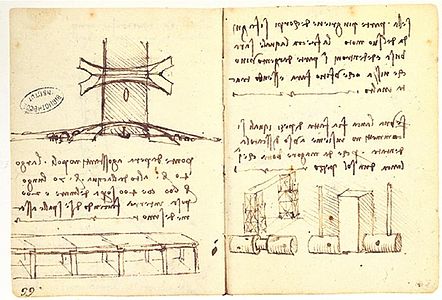

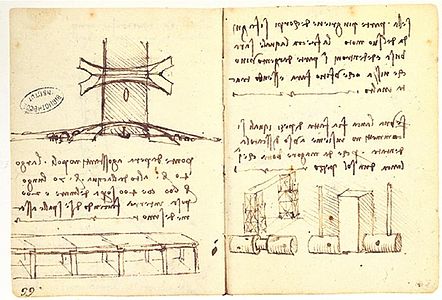

Leonardo da Vinci proposed a bridge 240 m (790 ft) long, overall and 24 m (79 ft) wide over the Golden Horn in 1502 for Sultan Bayezid II of Constantinople (today's Istanbul). The sketch and letter proposal were lost for over 400 years before being rediscovered in 1952.[1] The proposed bridge included a 240 m (790 ft) "pressed bow" main span with 43 m (141 ft) of vertical clearance to allow ships to pass.[2][3] da Vinci bragged that "it has been [the Sultan's] intention to erect a bridge from Galata (Pera) to Stambul… across the Golden Horn (‘Haliç’), but this has not been done because there were no experts available. I, your subject, have determined how to build the bridge. It will be a masonry bridge as high as a building, and even tall ships will be able to sail under it."[3][4] The sketch was confirmed to be a genuine work of da Vinci by comparison with an identical sketch in Manuscript L, part of the Paris Manuscripts stored in the Institut de France in Paris.[3]

Had the 1502 design been implemented, it would have been the longest bridge in the world,[5] and it would still be the longest single masonry arch span in the world. Da Vinci is said to have been inspired by the then newly built bridge "Ponte degli Alidosi" over Santerno at Castel del Rio near Bologna with a 42 m high semicircular arch.[6]

In 2019, a research team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology tested the stability of da Vinci's design by building a 1:500 scale model using only blocks without using fasteners or mortar, replicating contemporary masonry construction techniques. The bridge was first analyzed using a 3D model, then divided into 126 individual blocks which were individually printed, consuming approximately 6 hours per block. Falsework was used to temporarily support the blocks during construction of the scale model. After the falsework was removed, the model proved to be stable under load, and the spread-footing design proposed by da Vinci was able to resist movement of the foundation.[7]

Implemented in Ås[]

Norwegian artist Vebjørn Sand saw da Vinci's Haliç bridge sketch in 1996 and proposed the bridge should be implemented by the Norwegian Public Roads Administration (NPRA). Since the NPRA had a policy to consider the artistic merits of public structures,[8] a new structure was approved in 1997[9] to replace "Norway's ugliest bridge."[10] Several alternative materials were considered for the bridge, including the as-designed stone and concrete,[9] but ultimately the timber version was selected for construction. Moelven Laminated Group, who had constructed the world's largest wooden roof for Håkons Hall in Lillehammer for the 1994 Winter Olympics, was selected to supply glued laminated timber (glulam) for the new da Vinci Bridge.[8]

The da Vinci Bridge, completed in 2001, serves as a pedestrian crossing over highway E18 in Ås, approximately 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Oslo. It was built from large prefabricated glulam sections moved in place by cranes, with three parabolic arches in the main span: a central arch supporting the pathway and two stabilizing arches flanking it.[11] The main span is 40 m (130 ft) and the bridge is 109 m (358 ft) long, overall at a total cost of approximately 12 million Norwegian kroner.[12] The completed da Vinci Bridge was built wide enough to allow four lanes of traffic underneath, but requirements for vertical clearance have increased and adding lanes of traffic would require lowering the road.[10] The bridge was opened by Queen Sonja in a November 2001 ceremony using cranes to lift a white cloth draped over the bridge, literally unveiling it to the public.[5]

Since its unveiling, the da Vinci Bridge has attracted attention in the New York Times.[13][14] Wired called it one of the five coolest bridges on earth in 2005, along with the Rio–Antirrio bridge, the Seri Wawasan Bridge, the Dongting Lake Bridge and the Juscelino Kubitschek Bridge.[15]

Global Leonardo Bridge Project[]

The Oslo Leonardo Bridge Project opened in October 2001.[16] The project hopes to apply the design to build practical footbridges around the world using local materials and local artisans as a global public art project.[17] Future plans, announced in 2012, include a bridge over the Golden Horn in Istanbul, as Leonardo had proposed.[18] Sand was quoted by the Wall Street Journal describing the Bridge Project as a "... logo for all the nations."[2]

A small da Vinci pedestrian bridge was erected in 2016 at the Château du Clos Lucé, da Vinci's home for the last years of his life.[19] Other permanent da Vinci bridges have been proposed for several locations, although these plans have not come to fruition:

- Des Moines, Iowa (1998),[20] rejected as the design was said to be "too modern"[21]

- Arlington, Virginia (2002) to replace the old Doubleday Bridge over Spout Run Parkway[22][23][24]

- Roosevelt Island (2012)[25]

Several temporary da Vinci bridges have been built in ice since the completion of the da Vinci Bridge in Norway:[11]

- Queen Maud Land, Antarctica (2006), with the intention that it does not melt due to climate change[26]

- UN Plaza in New York City (2007),[26] approximately 30 feet (9.1 m) long[27]

- Ilulissat on Disko Bay in Greenland (2009)[19][28]

- Christiansborg Palace Square in Copenhagen (2009), a 52-foot (16 m) span for COP15[29][30]

- Juuka, Finland (planned 2016), a project led by the Eindhoven University of Technology to build a scale model of the 1502 bridge proposal using pykrete[31][32][33]

Gallery[]

Golden Horn Bridge designed by Leonardo da Vinci in 1502

Wooden model of da Vinci's Golden Horn bridge

Completed da Vinci bridge, side view

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Da Vinci Planned Bosporus Bridge for Turks in 1503". The Day. New London, Connecticut. AP. 26 March 1952. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b Morris, Jan (5 November 2005). "Spanning Past and Present". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Atalay, Bulent (22 January 2013). "LEONARDO'S BRIDGE: Part 2. 'A Bridge for the Sultan'". NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY NEWSROOM [blog]. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Leonardo's Design". The Leonardo Bridge Project. 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ a b Mellgren, Doug (1 November 2001). "Da Vinci comes to life 500 years on". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Pedretti, Carlo (1977). The Literary Works of Leonardo Da Vinci, Volume 1. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 212–214, note 1109. ISBN 0-520-03329-9. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Chandler, David L. (October 9, 2019). "Engineers put Leonardo da Vinci's bridge design to the test". MIT News. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Vebjørn Sand's Leonardo Bridge Project". The Leonardo Bridge Project. 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-04-30. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ a b Skari, Bent, ed. (2010). Statens vegvesen: Akershus 1990–2000 (PDF). Oslo, Norway: Statens vegvesen. p. 214. ISBN 978-82-994614-2-9. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

1997 arbeidet etaten med et spesielt prosjekt som gikk ut på å bygge ei bru etter samme prinsipp som tegnet av Leonardo Da Vinci i 1502. Den var tenkt satt opp som gangbru ved Nygårdskrysset over E18 ved Ski. Det ble jobbet med to alternativer – det ene i stein og betong, det andre i tre. Prosjektet har fått stor oppmerksomhet og pressedekning.

- ^ a b Foseid, Maren; Ljunggren, Tore; Fyksen, Stein; Slapgård, Snorre; Meland, Arne; Bakken, Frode (14 January 2015). Rapport Verdianalyse E18 Vinterbro – Retvet (PDF) (Report). Statens vegvesen. p. 16. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

Dagens gangbru ble bygget i 2001-02 som et kunstprosjekt, brua avløste «Norges styggeste bru», og var en stor forbedring på åpningtidspunktet, til tross for at brua har sterk stigning. Ved planlegging av brua var det skissert en sentrisk utvidelse av E18 til firefelts veg med bredde 19 meter, og brua er tilpasset en slik utvidelse. I ettertid er kravene til fri høyde under trebruer økt, og normalprofilet for E18 har økt til 25,5 meter. Brua tilfredstiller heller ikke UU- kravene.En utvidelse av E18 under dagens bru er mulig, men krever en senkning av dagens veg.

- ^ a b Atalay, Bulent (3 February 2013). "LEONARDO'S BRIDGE: Part 3. 'Vebjørn Sand and Variations on a Theme by Leonardo'". NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY NEWSROOM [blog]. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Dion, Richard (14 October 2013). "Leonardo Da Vinci's Golden Horn sketch – from Istanbul, via Norway to New York's Roosevelt Island". The Bridge Museum [blog]. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Hall, Peter (8 November 2001). "CURRENTS: SCANDINAVIA -- ARCHITECTURE; Leonardo, if You Could Only Have Lived to See This Day". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Nash, Eric P. (9 December 2001). "TRAVEL ADVISORY; After 500 Years, Leonardo Gets His Bridge". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Goldenberg, David (January 2005). "Spanning the Globe". Wired. Vol. 13 no. 1. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Global Leonardo Bridge Project". The Leonardo Bridge Project. 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-05-01. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ "About Us". The Leonardo Bridge Project. 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

The Leonardo Bridge Project, Inc. is a non-profit corporation in the United States with a 501(c) 3 through the Allied Arts Foundation. Our mission is to build a global network of permanent landmark bridges, public arts projects based on Leonardo da Vinci's 1502 “Golden Horn” (Haliç) bridge design.

- ^ "Da Vinci's Bridge to be built in Istanbul". Hürriyet Daily News. Istanbul. 23 October 2012. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b "New in 2016: The Golden Horn Bridge" (PDF). Château du Clos Lucé. 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Leonardo da Vinci". The Des Moines Register. 20 August 1998. p. 20. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Raynham, Alex (2015). "6: Leonardo's City". Leonardo da Vinci. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0194630788. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Jenkins, Chris L. (16 January 2003). "A Great Divide". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Spout Run Bridge Proposal". Arlington County Civic Federation. 27 December 2003. Archived from the original on 7 January 2004. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ von Bernewitz, Carla (July 2002). "Spout Run, Arlington Proposal" (PDF). Arlington County Civic Federation. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Luce, Jim (3 June 2012). "Roosevelt Island Art Bridges Two NYC Boroughs". The Huffington Post [blog]. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Ice bridge, art exhibit to highlight climate change at Headquarters 17 December" (Press release). United Nations. 14 December 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "U.N. ice bridge reminder of melting Antarctica". Reuters. 18 December 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Lynch, Elizabeth (July–August 2009). "Commissions" (PDF). Sculpture. Vol. 28 no. 6. Washington DC: International Sculpture Center. pp. 24–25. ISSN 0889-728X. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Cruger, Roberta (6 December 2009). "Bridge to Somewhere: DaVinci's Design on Ice". treehugger. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Ferrold, Hasse (10 December 2009). "LIVE ICE - "Leonardo da Vinci" inspired ICEBRIDGE at COP15 5/12 2009 in front of Christiansborgn Palace Copenhagen". International Club Copenhagen [blog]. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "World's Longest Bridge in Ice".

- ^ Rabida, Kevin Mark (6 January 2016). "Students Use Leonardo's Design to Build World's Longest Bridge From Ice". UCreative. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Eindhoven team to build Da Vinci bridge with a span of 50 meters" (Press release). Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Da Vinci-Broen, Ås, Akershus, Norway. |

External links[]

- Leonardo Bridge project home page

- Da Vinci bridge on BridgeInfo.net

- Leonardo's Bridge at Structurae

- Atalay, Bulent (17 January 2013). "LEONARDO'S BRIDGE: Part 1. 'The Master of all Trades'". NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY NEWSROOM [blog]. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "The Leonardo bridge project". The Happy Pontist [blog]. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Bouwman, Jules; Dalenoord, Coen; de Boer, Stijn; Meijerman, Thomas; Resoort, Sanne; van Breemen, Stan; van den Boer, Jeannine (January–February 2016). "Da Vinci Bridge in Ice - best of selection". flickr (Structural Ice). Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- A modern bridge reminiscing Leonardo's design, though with steel pillar support, is the Streicker Bridge at Princeton University, NJ, USA.

- Streicker Bridge project information and photos

- Streicker Bridge at Princeton

- Bridges in Viken

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Norwegian art

- Footbridges